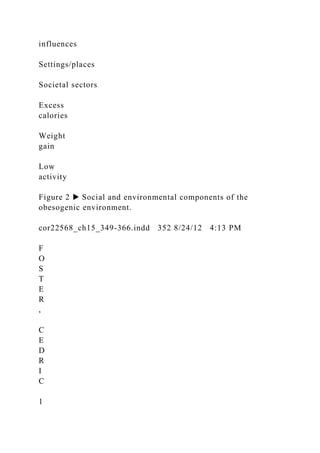

The document outlines key learning objectives related to nutrition, emphasizing the importance of healthy eating patterns and dietary guidelines. It discusses national dietary recommendations aimed at reducing health risks associated with poor nutrition while promoting a balanced intake of essential nutrients. Additionally, it highlights flexible dietary approaches and the role of carbohydrates as a primary energy source, debunking misconceptions surrounding their impact on health.

![1

6

9

2

T

S

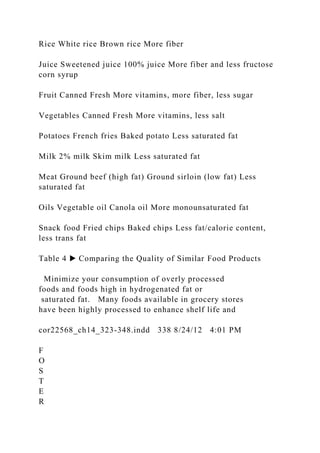

Concept 14 ▶ Nutrition 331

amounts of omega-3 fatty acids from marine sources

(e.g., docosahexaenoic acid [DHA] and eicosapentae-

noic acid [EPA]).

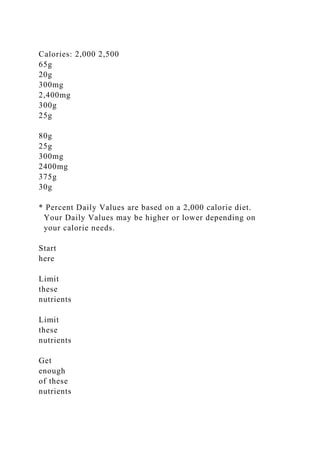

Dietary Recommendations

for Proteins

Protein is the basic building block for the body,

but dietary protein constitutes a relatively small

amount of daily caloric intake. Proteins are often

referred to as the building blocks of the body because all

body cells are made of protein. More than 100 proteins

are formed from 20 different amino acids. Eleven of

these amino acids can be synthesized from other nutri-

ents, but 9 essential amino acids must be obtained

directly from the diet. One way to identify amino acids is

the -ine at the end of their name. For example, arginine

and lysine are two of the amino acids. Only 3 of the 20

amino acids do not have the -ine suffix. They are aspartic

acid, glutamic acid, and tryptophan.

Certain foods, called complete proteins, contain all of

the essential amino acids, along with most of the others.

Examples are meat, dairy products, and fish. Incomplete

proteins contain some, but not all, of the essential amino

acids. Examples include beans, nuts, and rice.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/323learningobjectivesaftercompletingthestudy-221112170949-617e0a8e/85/323-LEARNING-OBJECTIVES-After-completing-the-study-docx-28-320.jpg)

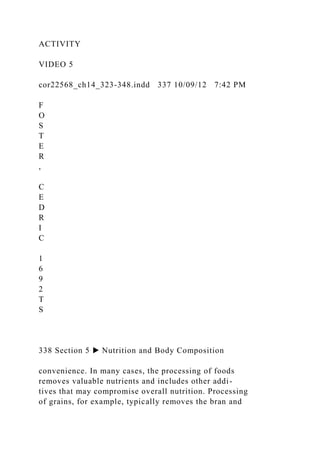

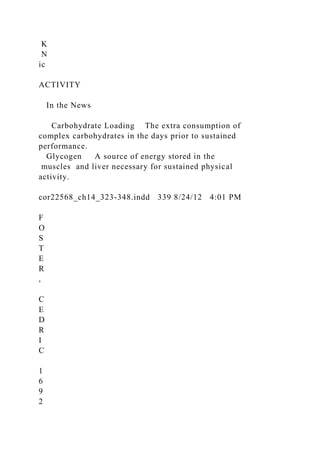

![drinks per day for men (one drink equals 12 ounces

of regular beer, 5 ounces of wine [small glass], or one

average-size cocktail [1.5 ounces of 80-proof alcohol]).

Making Well-Informed

Food Choices

Well-informed consumers eat better. Most people

underestimate the number of calories they consume daily

and the caloric content of specific foods. Not surpris-

ingly, people who are better informed about the content

of their food are more likely to make wise food choices.

Ways to get better food choice information include accu-

rate food labels on packages and information about food

content on menus or signs in restaurants.

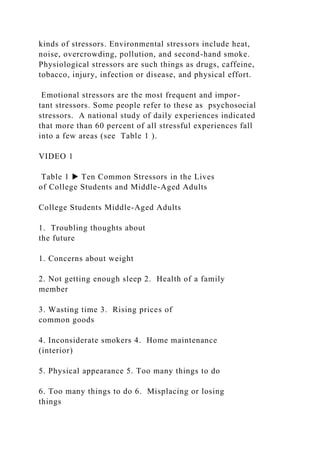

The content of food labels changes from time to time

depending on federal guidelines and policies. The most

recent change is the requirement to post trans fat content

on labels (see Figure 4 ). This action was prompted by the

clear scientific evidence that trans fats are more likely

to cause atherosclerosis and heart disease than are other

types of fat. Trans fats are discussed in a later section.

Reading food labels helps you be more aware of what

you are eating and make healthier choices in your daily

eating. In particular, paying attention to the amounts of

saturated fat, trans fat, and cholesterol posted on food

labels helps you make heart-healthy

food choices. When comparing

similar food products, combine the

grams (g) of saturated fat and trans

fat and look for the lowest combined amount. The listing

of % Daily Value (% DV) can also be useful. Foods low in

saturated fat and cholesterol generally have % DV values

less than 5 percent, while foods high in saturated fat and

cholesterol have values greater than 20 percent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/323learningobjectivesaftercompletingthestudy-221112170949-617e0a8e/85/323-LEARNING-OBJECTIVES-After-completing-the-study-docx-49-320.jpg)