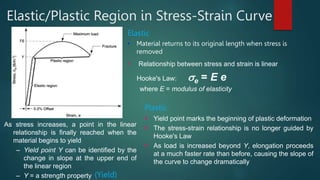

The document discusses various mechanical properties of materials important for manufacturing including modulus, yield strength, tensile strength, stress-strain relationships, ductility, toughness, hardness, and fatigue. It explains how properties like modulus, strength, and stress-strain behavior are evaluated using tensile tests, and how properties like ductility, toughness, and hardness are measured and related to a material's suitability for manufacturing processes. Comparative data on the mechanical properties of common materials like metals, ceramics, polymers is also presented.