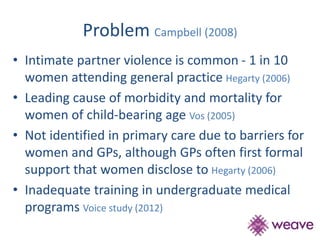

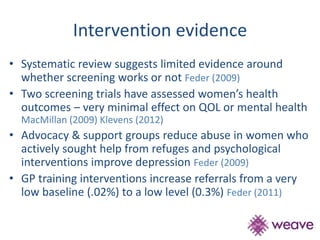

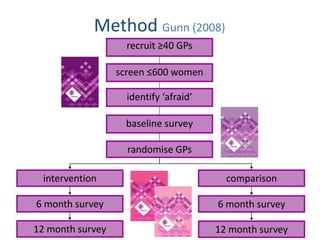

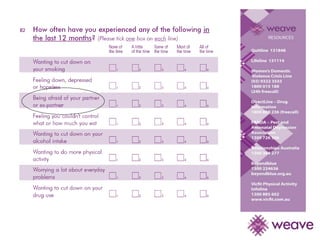

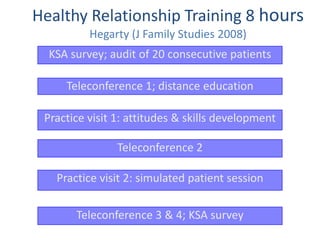

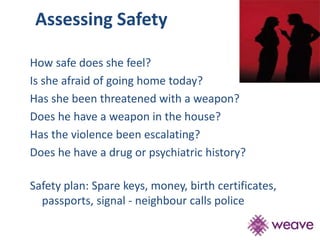

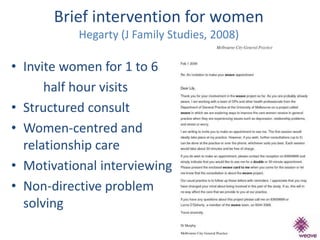

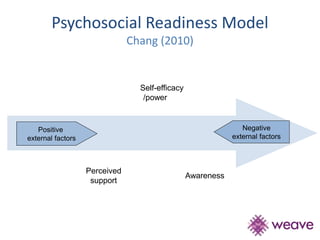

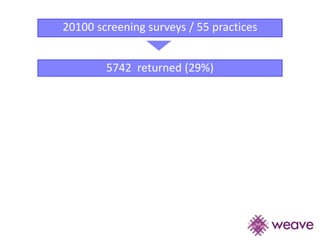

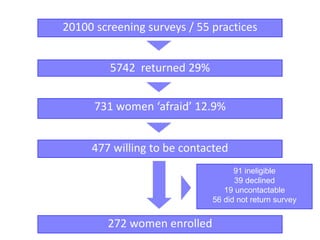

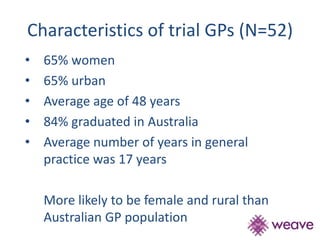

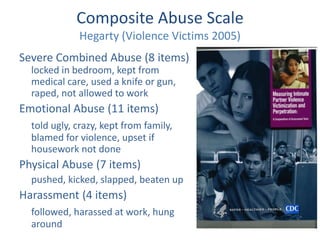

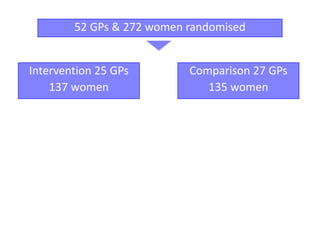

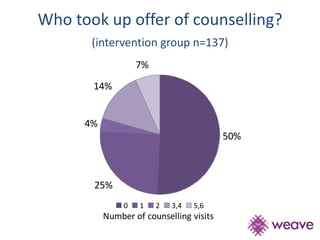

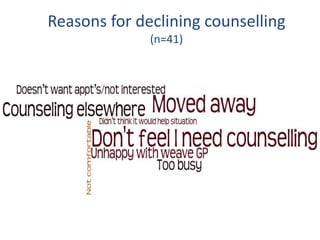

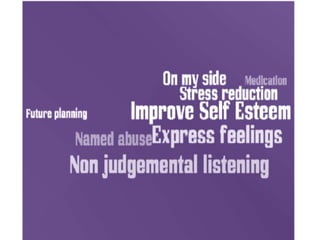

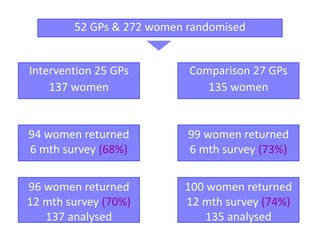

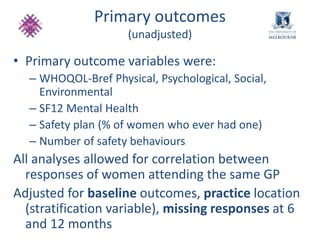

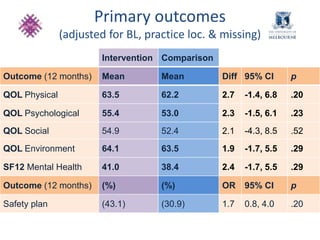

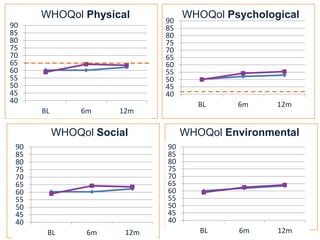

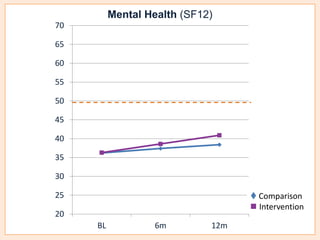

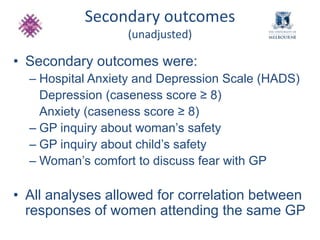

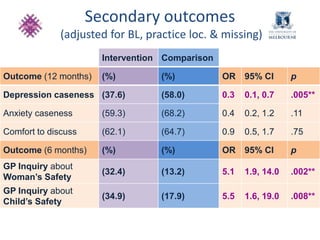

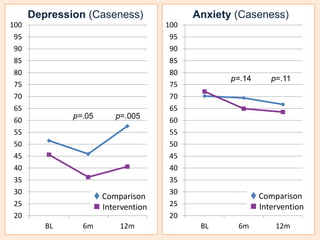

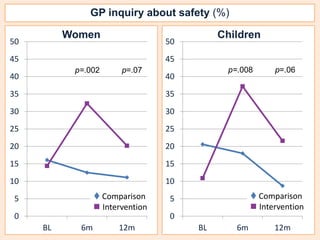

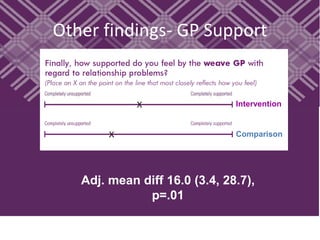

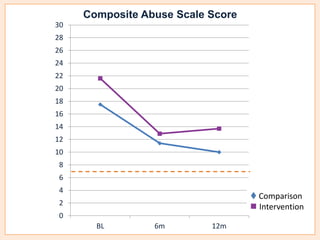

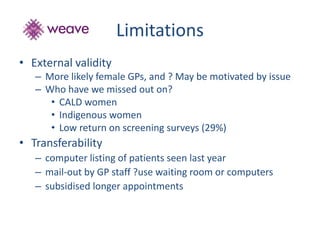

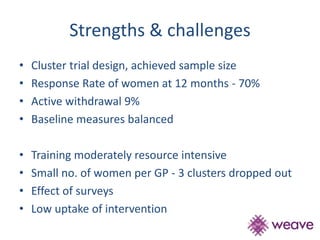

This document summarizes a study that evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention to address intimate partner violence in primary care. The intervention consisted of screening women for intimate partner violence, notifying and training general practitioners (GPs) to respond, and inviting screened women for brief counseling with their GP. The study found that the intervention led to a decrease in depressive symptoms for women and increased safety discussions between GPs and women about themselves and their children. However, the intervention did not significantly improve women's quality of life. The study provides preliminary evidence that screening and training GPs can help address intimate partner violence in primary care, though the training requires resources and uptake of counseling was low.