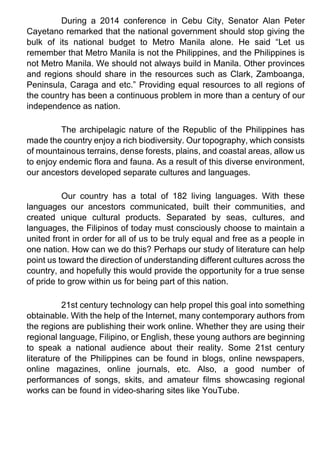

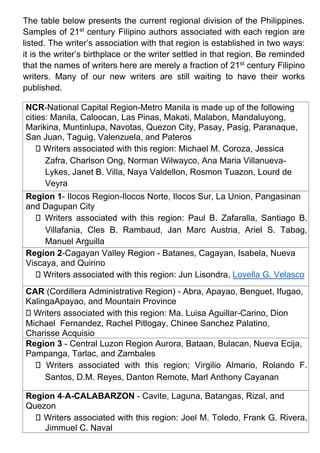

This document provides information about literature from the different regions of the Philippines. It begins by outlining the country's regional divisions and listing notable 21st century authors associated with each region. Examples of the works and contributions of some of these authors are then presented, including brief summaries of stories or poems by Manuel Arguilla and Aida Rivera-Ford. The purpose of the document is to familiarize the reader with representative texts and authors from the different regions of the Philippines.

![Source:

http://pinoylit.hy

perm art.net

Retrieved:

May 20, 2020

Source: http://pinoylit.hypermart.net

Retrieved: May 20, 2020

Source:

https://www.xu.edu.p

h/xavier-news

Retrieved:

May 25, 2020

Anthony Tan was born on 26 August 1947, Siasi

[Muddas], Sulu. His degrees AB English, 1968, MA

Creative Writing, 1975, and Ph.D. English Lit., 1982

were all obtained from the Silliman University where he

edited Sands and Coral, 1976. For more than a decade,

he was a member of the English faculty at SU and

regular member of the panel of critics in the Silliman

Writers Workshop. He taught briefly at the DLSU and

was Chair of the English Dept. at MSUIligan Institute of

Technology where he continues to teach. A member of

the Iligan Arts Council, he helps Jaime An Lim and

Christine Godinez-Ortega run the Iligan Writers

Workshop/Literature Teachers Conference. He also

writes fiction and children’s stories. He has won a

number of awards, among them, the Focus Award for

poetry, the Palanca 1st prize for Poems for Muddas in

1993; also, the Palanca for essay. Among his works are

The Badjao Cemetery and Other Poems, 1985 and

Poems for Muddas, Anvil, 1996.

Source:

https://www.xu.edu.ph/images/Kinaadman_Research_Cente

r/doc Retrieved: May 25, 2020

José Iñigo Homer Lacambra Ayala or also known as

Joey Ayala was born on June 1, 1956 in Bukidnon,

Philippines. He was known for his folk and

contemporary pop music artist in the Philippines, he is

also known for his songs that are more on the

improvement of the environment. He is a finalist of

Philippine Popular Music](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21stmodule2-210603030812/85/21-st-module-2-8-320.jpg)

![May lason na galing sa industriya

Ibinubuga ng mga pabrika

Ngunit 'di lamang higante

Ang nagkakalat ng dumi

May kinalaman din ang tulad natin

[Repeat chorus twice]

Karaniwang tao [4x]

[Repeat chorus]

Karaniwang tao

[Repeat till fade]

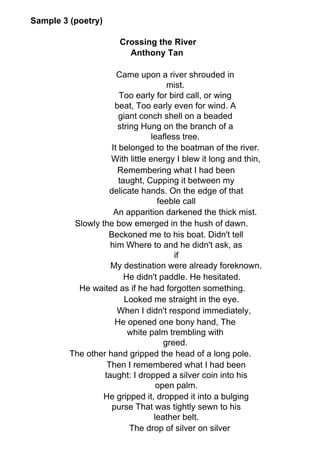

Activity 2. On your notebook, enumerate at least 3 contributions of

literature of each of the following writers:

1. Michael M. Coroza

2. Ivy Alvarez

3. Suzette Severo Doctolero

4. Anthony Tan

5. Manuel Arguilla

Activity 3. Appreciating literary pieces.

A. Noting Details. On your notebook, write the letter of your answer.

FROM THE STORY “MIDSUMMER” BY MANUEL ARGUILLA

1. The two contrasting images in the story are__

A. aridity and freshness

B. love and hate

C.hope and despair

2. Manong came upon Ading beyond a bend in the gorge where a big

__tree cast a cool shade

A. bamboo

B. atis

C.mango

3. Ading brought with her a __ when she met Manong.

A. jug

B. coconut shell](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/21stmodule2-210603030812/85/21-st-module-2-25-320.jpg)