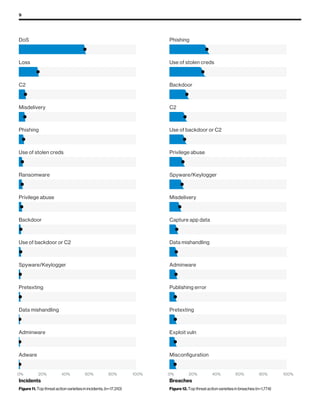

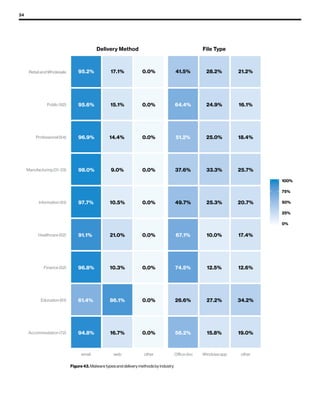

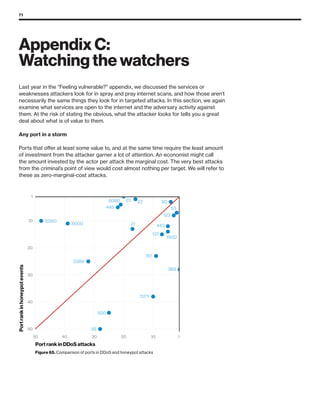

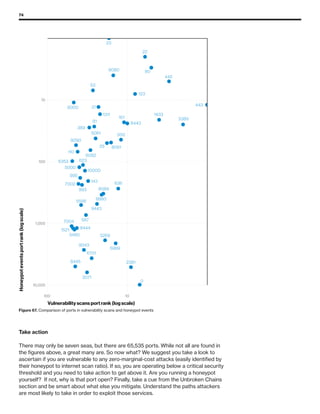

The 2019 Data Breach Investigations Report analyzed 41,686 security incidents, with 2,013 confirmed data breaches, revealing that external actors were primarily responsible for 69% of breaches and that financial gain remains the main motive. Key findings include that 43% of breaches involved small businesses, 33% were linked to social attacks, and hacking accounted for 52% of incidents. The report emphasizes the importance of understanding threat actions and actor motivations in improving cybersecurity measures across various industries.