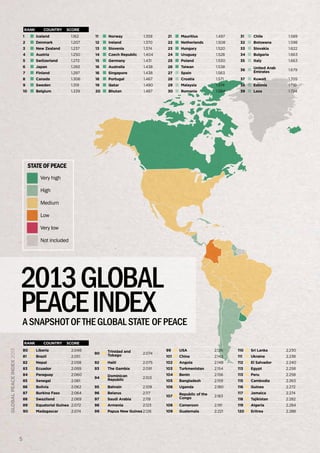

The document summarizes the key findings of the 2013 Global Peace Index report. The following are the main points:

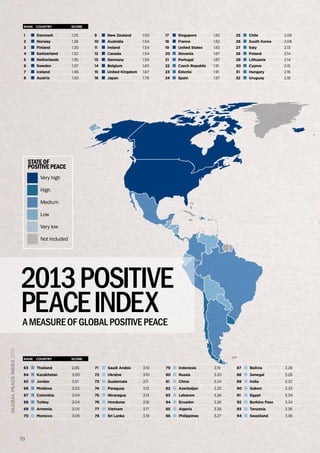

1) The world became slightly less peaceful in the last year, continuing a six-year trend of declining peacefulness. Internal conflicts have increased while large inter-state conflicts have declined.

2) Iceland remains the most peaceful country. The ten most peaceful are small, stable democracies. Europe is the most peaceful region while South Asia is the least peaceful.

3) Afghanistan returned to being the least peaceful country while Somalia improved slightly. Syria had the largest deterioration due to civil war.

4) The economic impact of containing violence globally is estimated at $9.46 trillion or

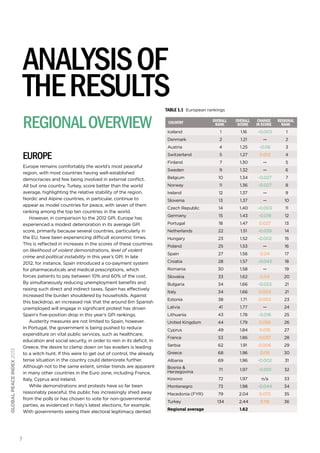

![3

There has been a 5% deterioration

in the Global Peace Index score

over the last six years, indicating

a less peaceful world.

The ten highest ranking nations in the GPI are all

relatively small, stable democracies, with Nordic and

Alpine countries particularly well represented. Europe

is comfortably the most peaceful region; few countries

are involved in external conflict and most societies are

broadly harmonious. Nevertheless, several European

countries experienced less peaceful conditions amid

challenging economic circumstances, including Spain,

Greece, France and Portugal. North America is the

second-most peaceful region, followed by Asia-Pacific,

which is buoyed by high rankings for New Zealand (2nd)

and Japan (6th), as well as Australia, Singapore, Taiwan

and Malaysia, all of which lie in the top 30.

Libya experienced the greatest rise in peacefulness, with

a newly elected government and recovering institutions

following the turmoil of the recent revolution and civil war.

Sudan and Chad experienced the second and third-most

substantial gains as their respective conflicts eased, but

conditions in areas of both countries are far from peaceful

and they remain in the lower reaches of the GPI.

Uruguay and Chile stand out as the two most peaceful

South American nations, characterised by relatively strong

institutions and the rule of law. Conditions worsened in

third-ranked Argentina amid a series of trade spats with

neighbours. In Central America, Costa Rica again emerges

as the most peaceful nation, although it suffered from a

decline in internal peace. Nicaragua, Guatemala and El

[highlights]

results,findings

&methodology

3

globalpeaceindex2013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2013globalpeaceindexreport-140623175112-phpapp01/85/2013-global-peace_index_report-6-320.jpg)

![55

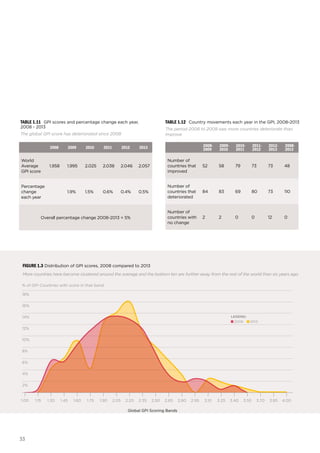

Were the world to reduce its

expenditure on violence by

approximately 50 per cent it could

repay the debt of the developing

world ($4076bn), provide enough

money for the European stability

mechanism ($900bn) and fund

the additional amount required

to achieve the annual cost of the

Millennium Development Goals

[summary]

TheGlobalCost

ofContaining

Violence

55

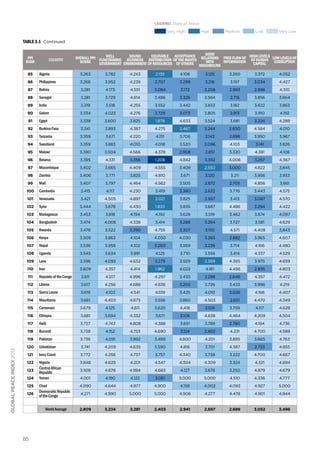

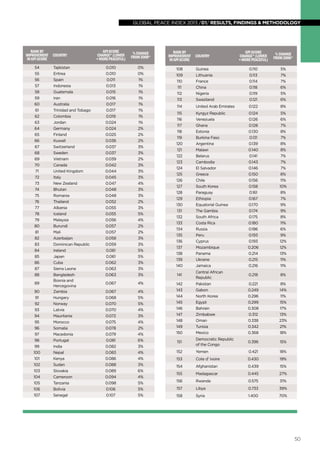

Calculating the cost of violence to the global economy

is notoriously difficult. In the past IEP has adopted a

methodology developed by Brauer and Tepper-Marlin (BTM

method) which reviewed existing literature on the cost of

violence, conflict and war and then estimated the additional

economic flow-on effects if these costs did not arise. To

complement this approach IEP has adopted a new and novel

method of estimating the cost of violence to the global

economy through calculating global violence containment

costs. IEP defines violence containment costs as economic

activity that is related to the consequences or prevention

of violence where the violence is directed against people or

property.

This approach uses ten indicators from the GPI and three

additional key areas of expenditure to place an economic

value on these thirteen different dimensions. This process

has been developed so that in addition to estimating the

global impact, the methodology could also be used to create

country based estimates. To enable relative comparisons

between countries at different levels of economic

development, GDP per capita has been used to scale the cost

of violence containment for each country. In both the US and

the UK a number of robust analyses have been conducted on

the cost of various types of violence and crime and used as

the basis for the scaling.

This study is highly conservative as there are many items

which have not been counted simply because accurate data

could not be obtained. Future studies will attempt to capture

these items; therefore future estimates are expected to be

much higher.

Using this methodology the economic impact of violence

containment to the world economy in 2012 was estimated

to be US$9.46 trillion or 11 per cent of Gross World Product

globalpeaceindex2013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2013globalpeaceindexreport-140623175112-phpapp01/85/2013-global-peace_index_report-58-320.jpg)

![global peace index 2013 /03/ POSITIVE PEACE INDEX 2013

78

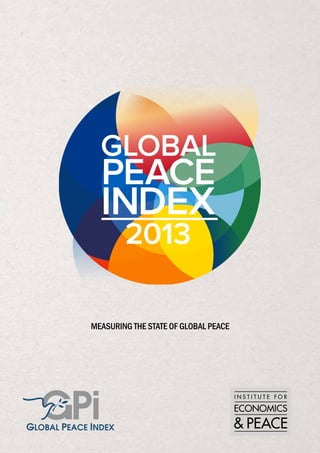

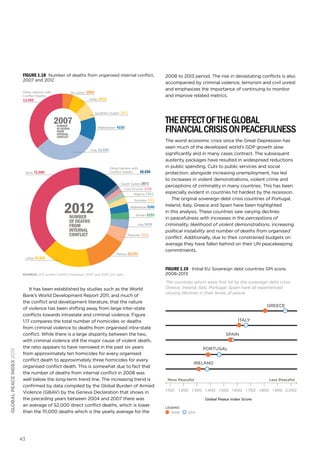

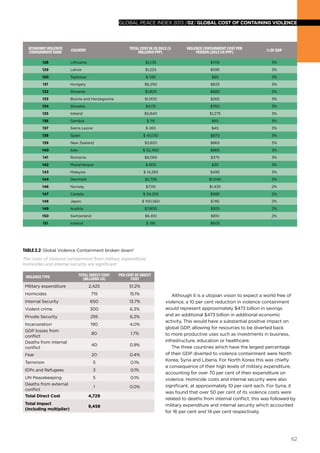

This is the second edition of the Positive Peace Index

(PPI), a measure of the strength of the attitudes,

institutions, and structures of 126 nations to determine

their capacity to create and maintain a peaceful society.

The PPI is based on a statistical framework which groups

these attributes into eight key categories known as the

‘Pillars of Peace’. These pillars have been identified as

describing what underpins a peaceful society.

The Pillars of Peace emphasise the importance of

a holistic set of institutions which work together to

systematically shape the environments that lead to peace.

This framework is not aimed at deriving causality between

any of the Pillars, rather they work as an inter-dependent

set of factors where causality can run in either direction

and the strength of the relationships between the Pillars

will change depending on the specific circumstances in a

particular country.

In constructing the Pillars of Peace, over 800 different

indexes, datasets and attitudinal surveys were analysed in

conjunction with a broad literature review about the key

factors that drive peace, resilience and conflict.

In order to ensure the final framework was holistic, a

multidisciplinary and ‘systems approach’ to the concept of

peace was used, drawing on recent research.

The 2013 PPI has ranked 126 countries on 24 indicators

and found that the global average of positive peace

improved in the period between 2005 and 2010 by 1.7%.

Globally there have been improvements in equitable

distribution of resources, levels of human capital, free flow

of information, levels of corruption, acceptance of the

rights of others and well-functioning governments.

North America and Europe remain the regions with the

highest levels of positive peace. Relative improvements

have been made in Asia-Pacific, South America, Central

America, MENA and Russia and Eurasia.

[highlights]

78

2013 global peace index /03/ POSITIVE PEACE INDEX 2013

21

Of the top 30

countries

are full

democracies

while

8are flawed

democracies

and

1isahybrid

regime](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2013globalpeaceindexreport-140623175112-phpapp01/85/2013-global-peace_index_report-81-320.jpg)