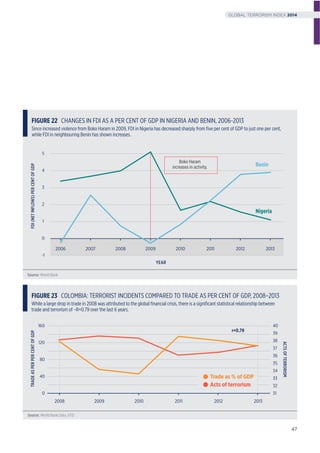

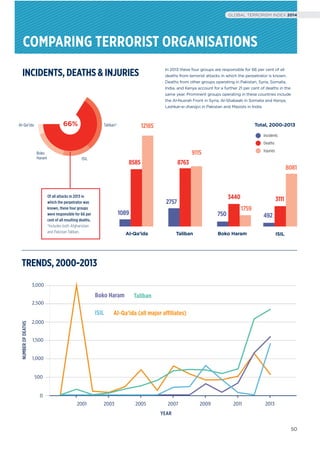

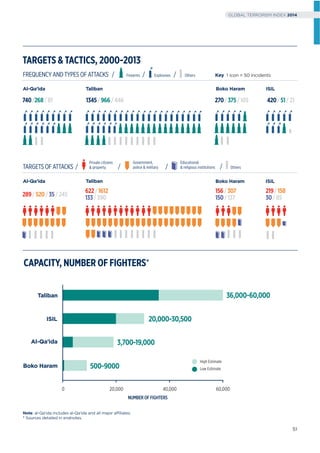

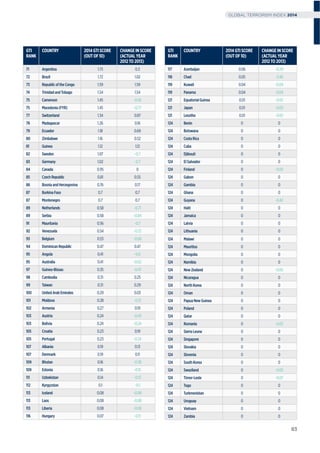

The Global Terrorism Index report analyzes trends in terrorism over the past 14 years. In 2013, deaths from terrorism significantly increased to over 17,000, with four terrorist groups (ISIL, Boko Haram, Taliban, al-Qa'ida) claiming 66% of deaths. Religious extremism based on interpretations of Wahhabi Islam motivates many groups, though political and separatist movements also use terrorism. Countries with high terrorism experience social divisions, state violence, and other forms of violence more than economic factors like poverty. The report identifies 13 countries at risk of substantial future increases in terrorism. Past successes against terrorism have involved policing or political processes more than military engagement alone.

![x40

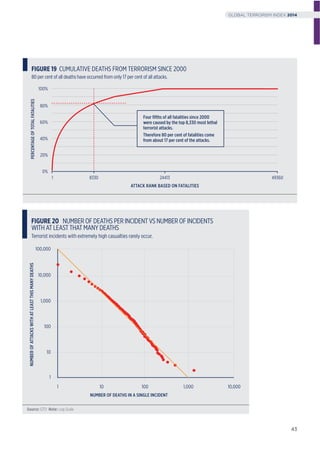

Comparing the number of deaths from homicide versus the

number of deaths from terrorism from 2000 to 2011 in the

four countries that experienced ‘black swan’ events it is

possible to compare the ratio between homicides and

terrorism. Four examples of significant ‘black swan’ incidents

since 2000 include the 2011 Norway attack, the 2004 Madrid

bombings, the 2005 7/7 London attacks and September 11.

A comparison of deaths from these four events to national

homicides of each country over the period of 2000 to 2011 is

shown in Table 5. What is apparent is that even in countries

which have experienced a devastating terrorist attack in the

last ten years; significantly more people were killed by

homicide than by terrorism over the period.

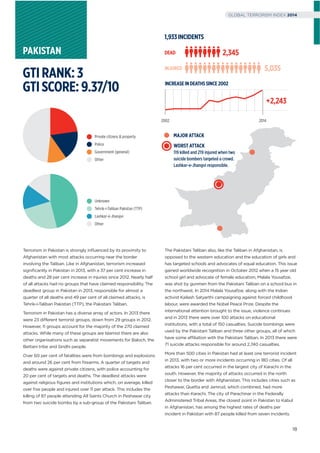

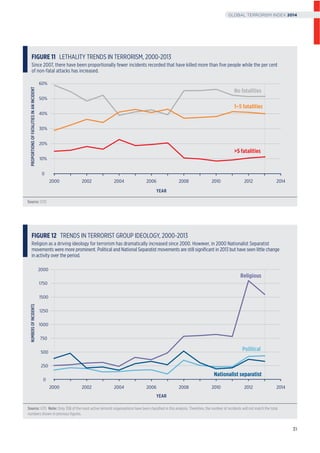

At the global level, the difference between deaths from

intentional homicide and terrorism is very significant. Figure

21 shows that in 2012 a total of around 437,000 lives were

lost due to homicide, by contrast in the same year, a total of

11,000 people were killed from terrorism representing a

number 40 times less than homicide.26 Therefore the

likelihood of being killed through intentional homicide is

much greater than being killed in a terrorist attack.

Of course while it should be noted that while terrorism may

claim fewer lives, its effect on a community is traumatic,

creating fear, changing daily habits and producing

substantial economic costs.

Source: GTD, UNODC Global Study on Homicide 2013

FIGURE 21 NUMBER OF DEATHS BY HOMICIDES

VS. TERRORISM GLOBALLY, 2012

Around 40 times more people were killed globally by

homicide than terrorism in 2012.

DEATHSIN2012

0

200,000

100,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

Homicides

437,000

Terrorism

11,000

COMPARING HOMICIDE TO

TERRORIST DEATHS

TABLE5 DEATHS BY HOMICIDE VS. DEATHS FROM

FOUR LARGE ‘BLACK SWAN’ EVENTS

Even in countries which have experienced a devastating terrorist

attack in the last ten years; significantly more people were killed by

homicide than by terrorism over the 2000-2011 period.

Country Deaths from

terrorism (T)

Homicides (H)

[1]

Ratio = (H – T)/

(T)

Norway 75 518 1:6

Spain 249 5,897 1:23

United Kingdom 57 10,776 1:188

United States 3029 195,948 1:64

TOTALNUMBEROFDEATHS 2000-2011

Source: UNODC, Homicide Statistics, http://www.unodc.org/gsh/en/data.html ,2013,

(accessed 7 October 2014).

AN INDIVIDUAL IS 40

TIMES MORE LIKELY

TO BE A VICTIM OF

HOMICIDE THAN

BE KILLED IN A

TERRORIST ATTACK.

44

GLOBAL TERRORISM INDEX 2014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/globalterrorismindexreport2014-150111052255-conversion-gate01/85/Global-terrorism-index-report-2014-46-320.jpg)