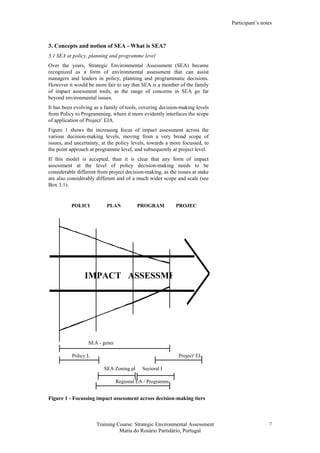

This document provides background information on the development of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). It discusses how SEA emerged due to limitations in traditional environmental decision-making and project-level environmental impact assessment in addressing complex, strategic decisions. Key events that contributed to the evolution of SEA include the US National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, which first required assessment of legislation and major federal actions, as well as initiatives by international organizations in the 1980s-1990s promoting SEA for policies, plans and programs. The document introduces the trainer and provides an outline of topics to be covered in the two-day SEA training course.