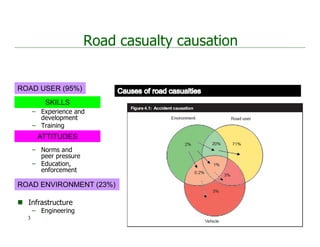

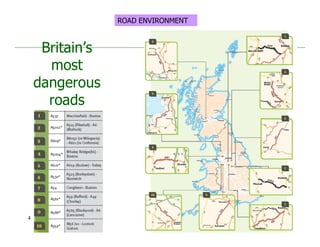

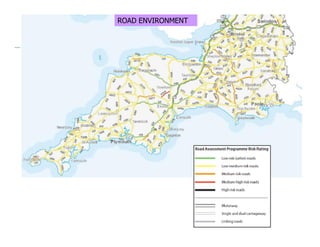

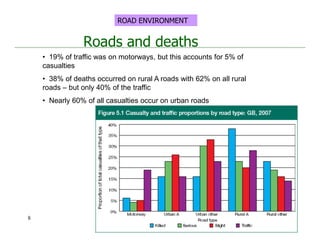

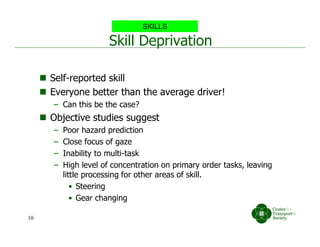

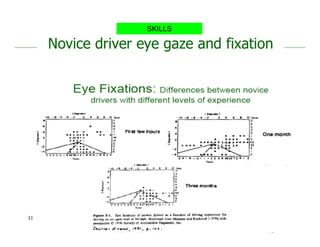

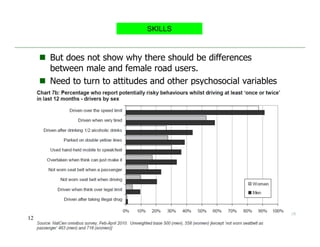

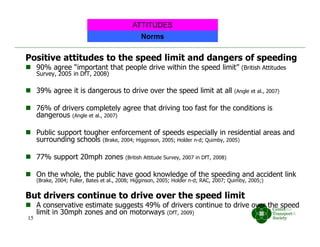

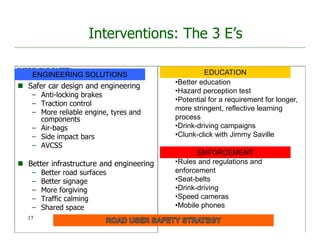

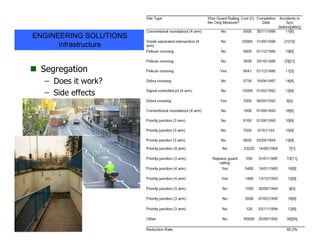

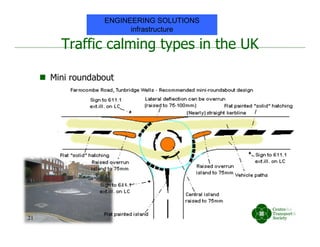

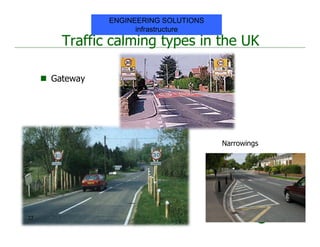

The document discusses strategies for improving road safety through the "3 Es" of education, enforcement, and engineering. It examines causes of road accidents such as driver skill, attitudes, and the road environment. UK policy approaches road safety through interventions that target these three areas, including road infrastructure improvements and traffic calming measures. Road safety audits aim to evaluate the safety of road designs.