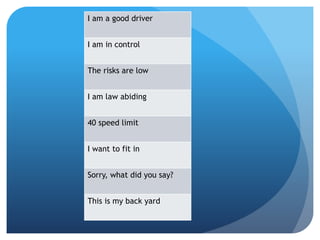

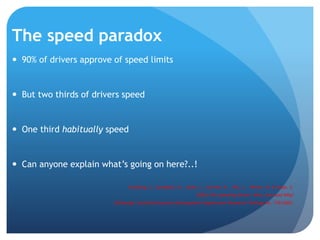

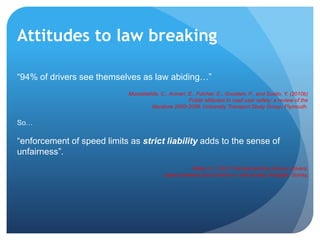

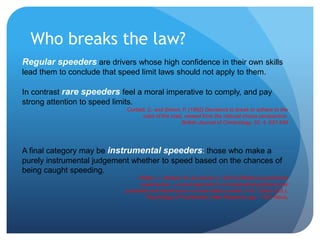

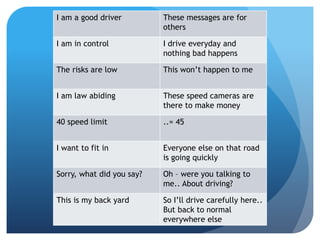

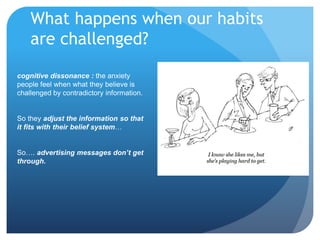

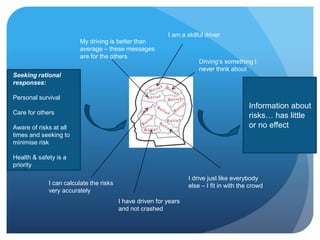

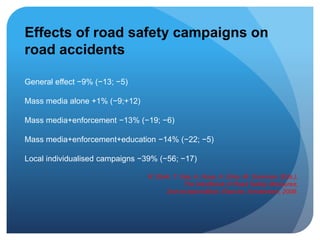

Professor Alan Tapp's presentation explores the psychological factors behind drivers' perceptions of their abilities, highlighting common biases such as the illusion of control and self-enhancement bias. Tapp discusses the discrepancy between drivers' approval of speed limits and their actual speeding behavior, suggesting that many drivers feel justified in exceeding limits due to overconfidence in their skills. The lecture emphasizes the need for innovative approaches in road safety campaigns to effectively address risky driving behaviors and improve compliance.