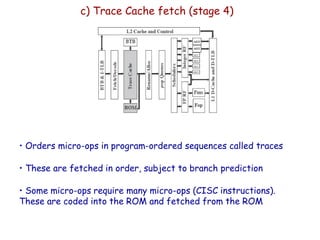

The document discusses superscalar processors and provides details about the Pentium 4 architecture as an example of a superscalar CISC machine. It covers topics such as instruction issue policies, register renaming, branch prediction, and the 20 stage pipeline of the Pentium 4 which decodes x86 instructions into micro-ops and executes them out-of-order. Dependencies limit instruction level parallelism, requiring techniques like register renaming and out-of-order execution to achieve higher performance in superscalar designs.