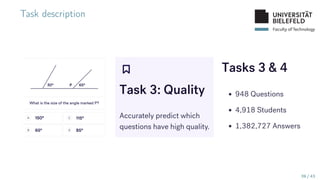

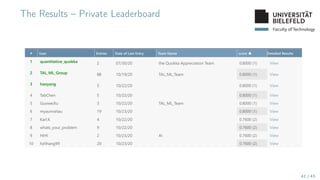

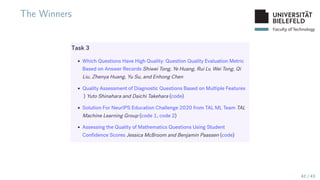

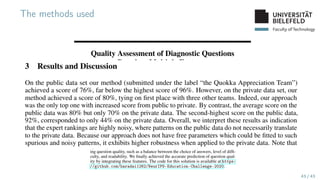

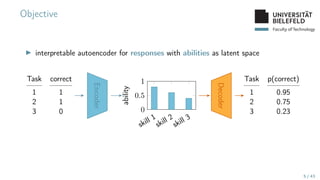

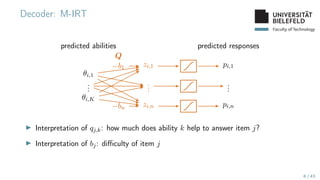

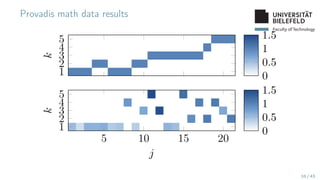

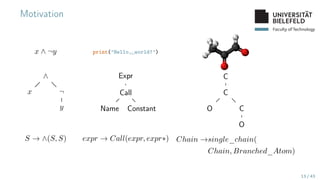

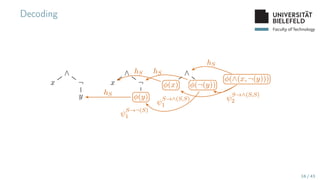

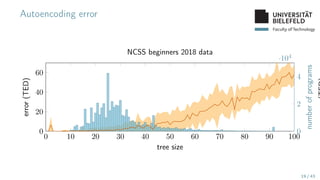

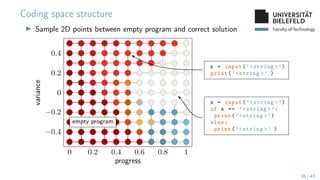

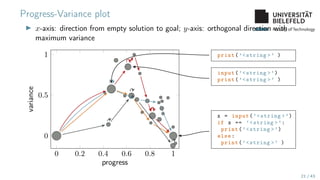

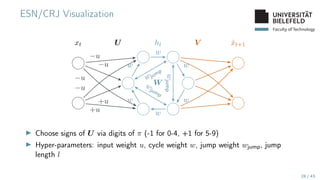

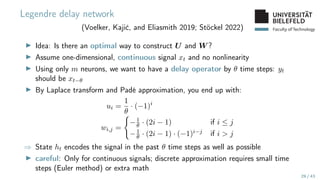

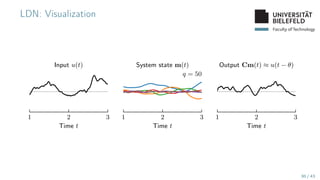

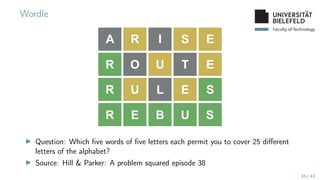

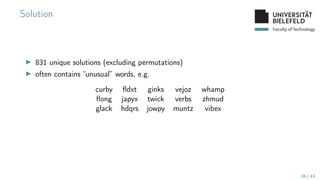

The document presents various topics in data mining, including autoencoders, tree grammars, and prediction methods. It discusses the development of interpretable models and their applications in tasks such as predicting student programming responses. Additionally, the document shares insights into competitions and runtime optimization concerns regarding algorithm performance.

![Faculty of Technology

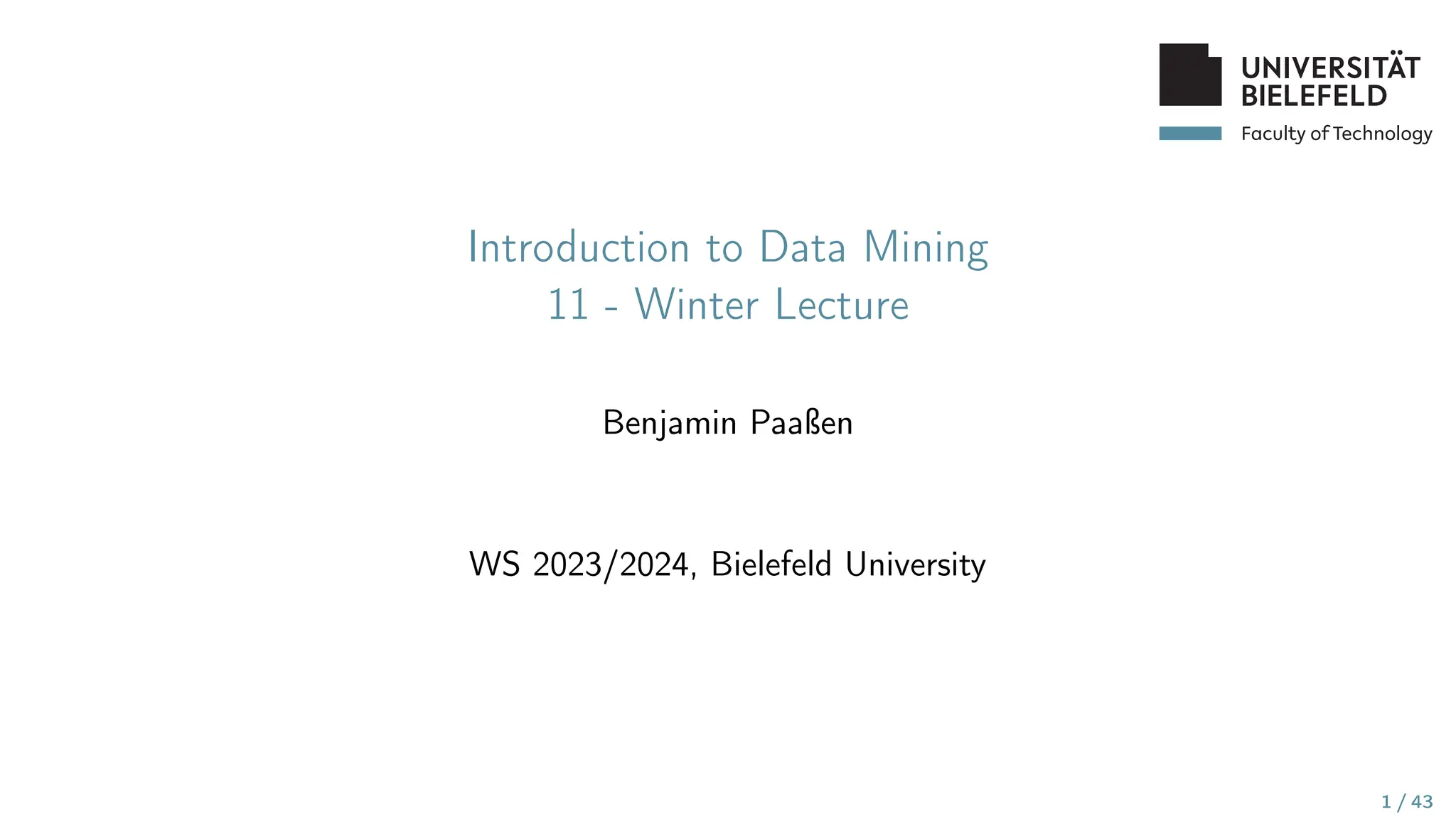

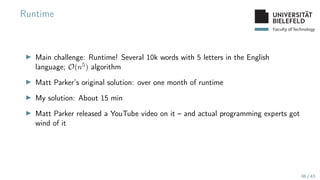

Runtime (continued)

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55

10−4

10−2

100

102

104

106

standupmaths

bpaassen

neilcoffey

IlyaNikolaevsky

gweijers

KristinPaget

orlp

oisyn

miniBill

oisyn stew675

stew675 GuiltyBystander

video release

days since podcast

runtime

[s]

Python

Java

C++

C

Rust

Julia

Go

▶ Full leaderboard: Link

▶ Second YouTube video: Link

37 / 43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/11winterlecture-240604204544-5f76bae0/85/11_winter_lecture-2023-2024-pdf-37-320.jpg)