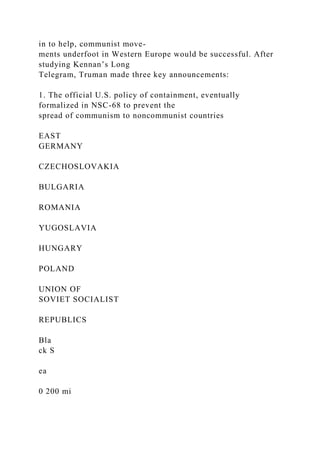

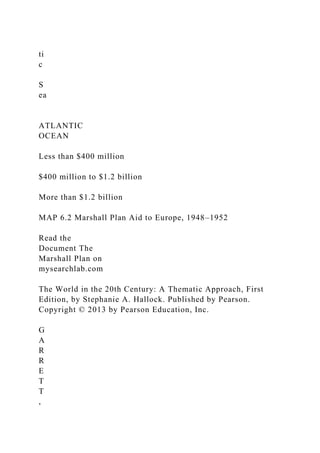

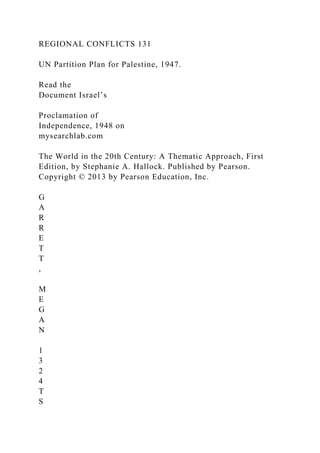

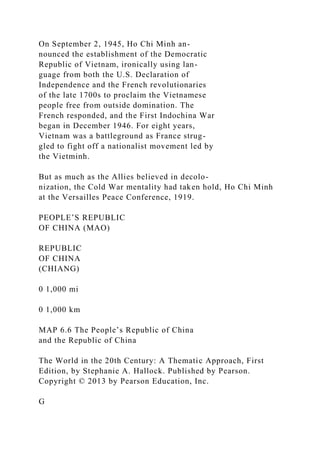

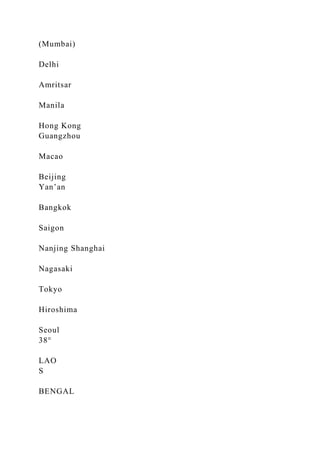

The document outlines the major events and geopolitical shifts from the end of World War II to the rise of the Cold War, highlighting the division of power between the United States and the Soviet Union. Key developments include the establishment of the United Nations, the decolonization of several countries, the ideological conflict over communism versus capitalism, and the technological advancements in warfare. The division of post-war Europe and the influence of the 'big three' allied leaders are discussed as critical factors shaping the ongoing tensions of the Cold War era.

![diplomat in Moscow since 1933, for

his view on Stalin’s intentions. His now-famous response, The

Long Telegram of February 22,

1946, warned that “in the long run, there [could] be no

permanent, peaceful coexistence” with

the Soviet Union. In Kennan’s mind, the conflict stemmed from

Stalin’s belief in Marxism and

his fear that Western capitalism would affect his people;

therefore, the American way of life had

to be destroyed. Probably the most important feature of this

Long Telegram is Kennan’s conclu-

sion regarding how best to handle the situation. Although Stalin

would never negotiate or com-

promise, the problem could be solved “without recourse to any

general military conflict.”

Ultimately, Kennan said, the Soviet system of government is

weaker than the American system

of government and American success “. . . depends on health

and vigor of our own society. . .

Every courageous and incisive measure to solve internal

problems of our own society, to

improve self-confidence, discipline, morale and community

spirit of our own people, is a diplo-

matic victory over Moscow. . .” The United States should firmly

guide other countries in devel-

oping political, economic, and social well-being “and unless we

do,” Kennan warned, “Russians

certainly will.” Kennan’s words became the cornerstone of

American foreign policy for most of

the remainder of the twentieth century.

A few weeks after Kennan’s telegram, Winston Churchill, the

former British prime minister,

spoke at a college in Fulton, Missouri. His speech was not well

received at the time—many

people viewed Churchill as a warmonger trying to drag the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/118chapteroutlineworldwideconflictwestern-221101135451-8e60a229/85/118CHAPTEROUTLINE-WorldwideConflict-Western-docx-17-320.jpg)