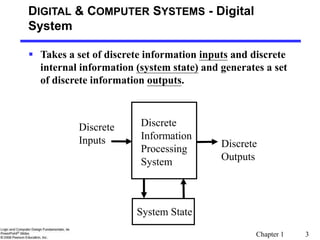

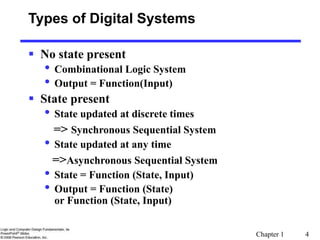

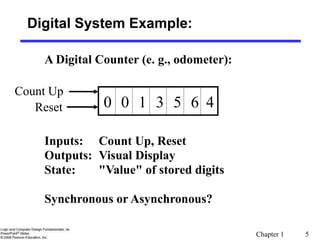

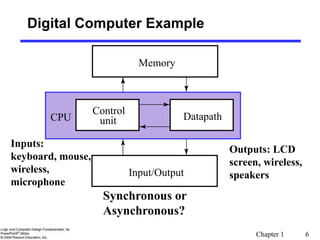

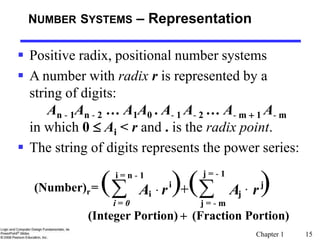

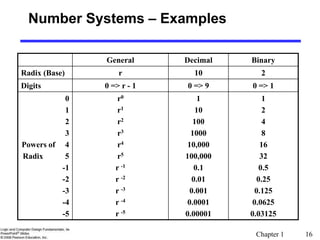

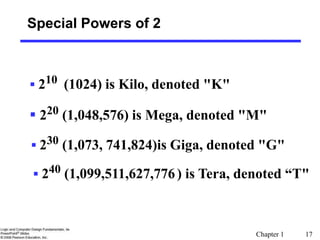

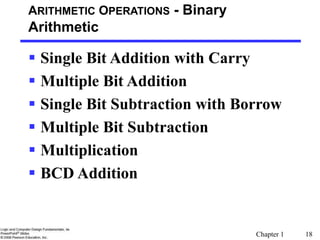

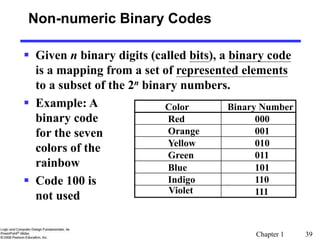

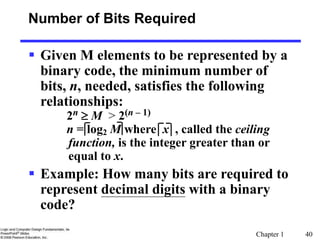

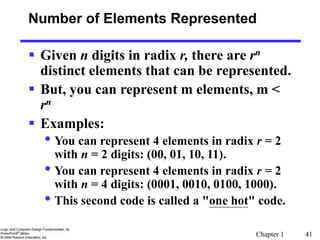

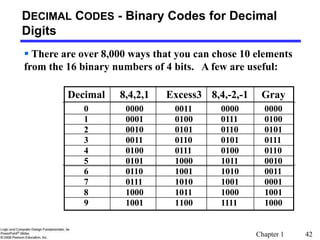

This document provides an overview of digital systems and information representation. It discusses key topics such as number systems, arithmetic operations, and coding. Digital systems take discrete inputs and outputs and can have state. There are different types including combinational and sequential systems. Information is represented using physical quantities mapped to discrete values, often binary digits. Common number systems like binary, octal, hexadecimal and their arithmetic are covered. Conversion between number systems and different number bases is also explained.

![Chapter 1 2

Overview

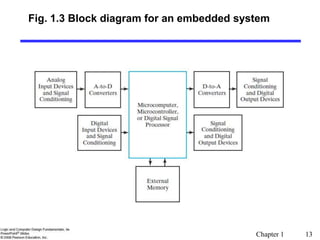

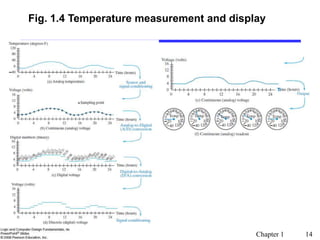

Digital Systems, Computers, and Beyond

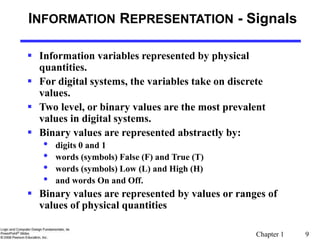

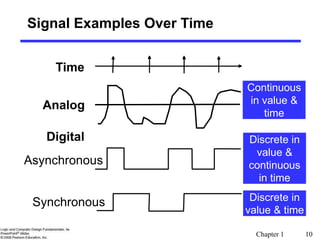

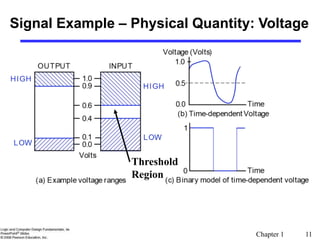

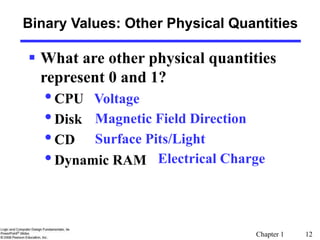

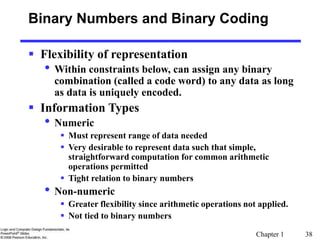

Information Representation

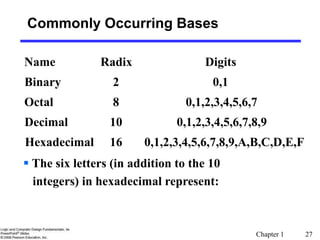

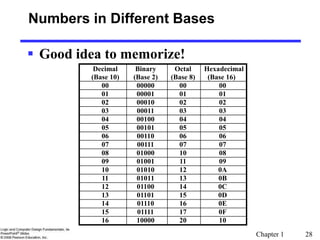

Number Systems [binary, octal and hexadecimal]

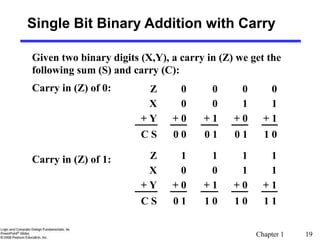

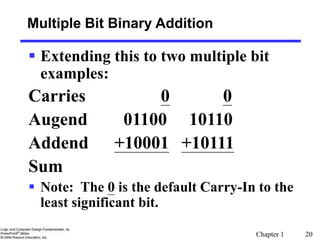

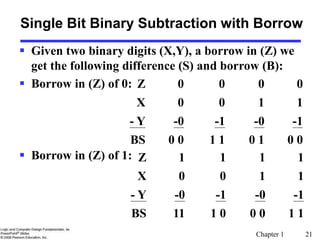

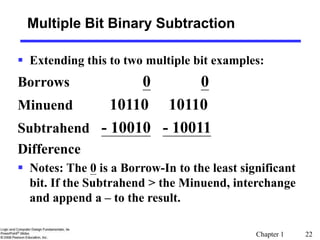

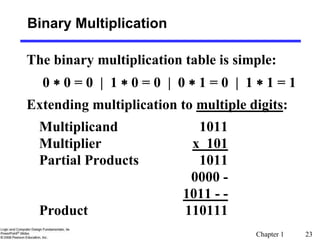

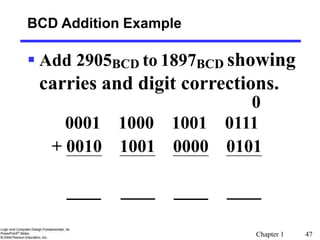

Arithmetic Operations

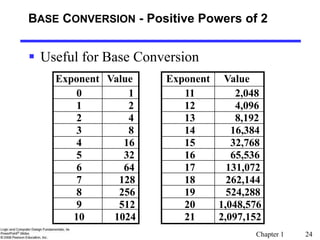

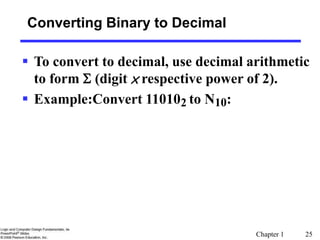

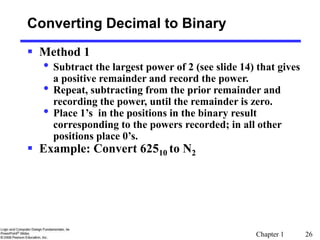

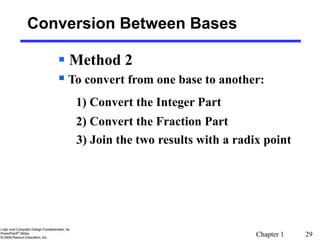

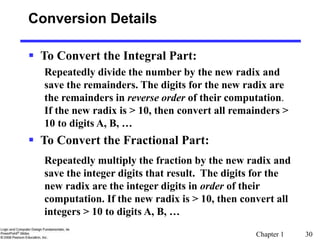

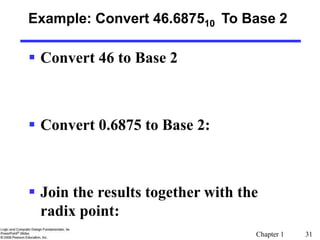

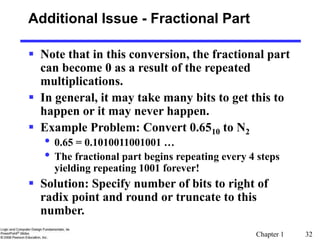

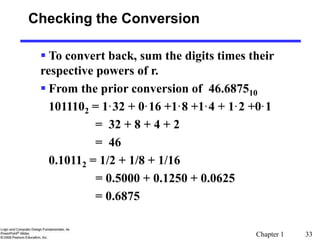

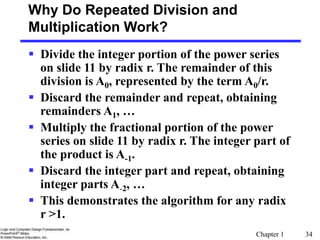

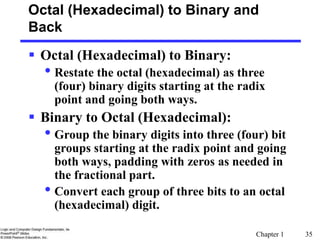

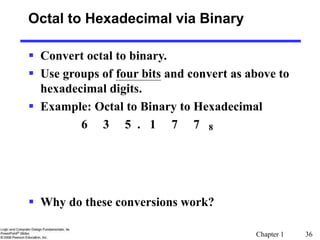

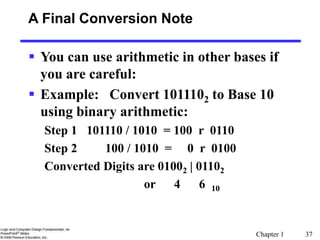

Base Conversion

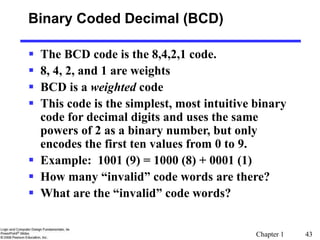

Decimal Codes [BCD (binary coded decimal)]

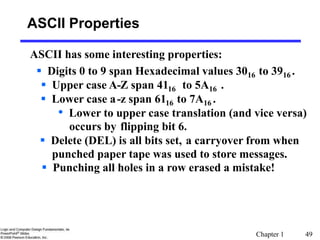

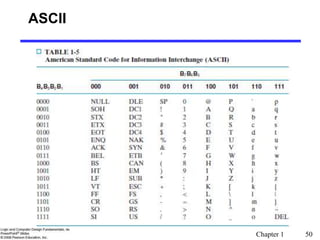

Alphanumeric Codes

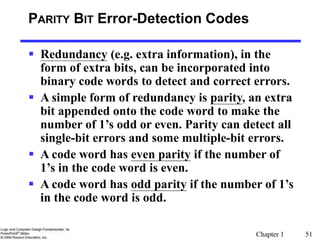

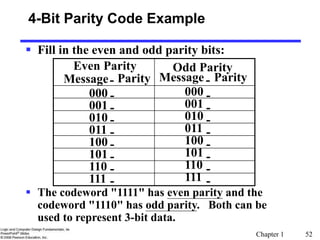

Parity Bit

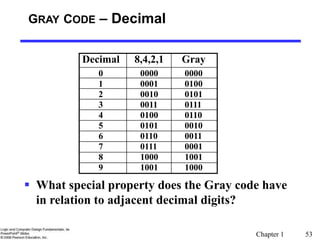

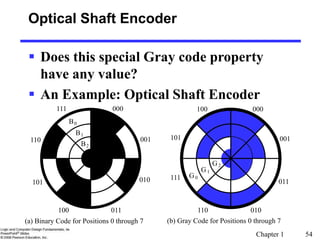

Gray Codes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1002digitalsystemchap12-240101172050-3403d38c/85/100_2_digitalSystem_Chap1-2-ppt-2-320.jpg)