This document provides an overview of fluid mechanics concepts including:

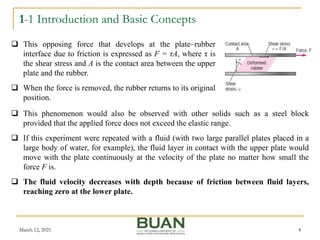

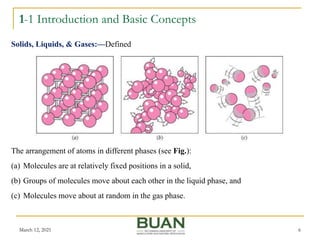

- The definition of a fluid and differences between solids and fluids

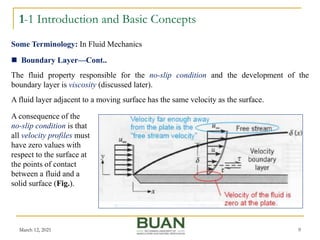

- Key terminology like stress, shear stress, and boundary layers

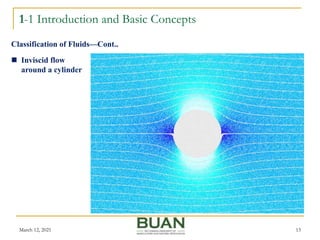

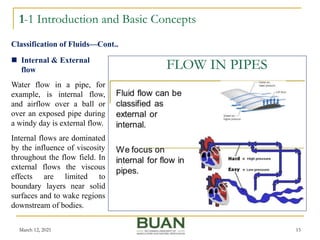

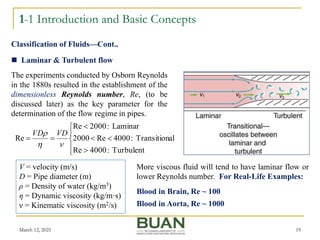

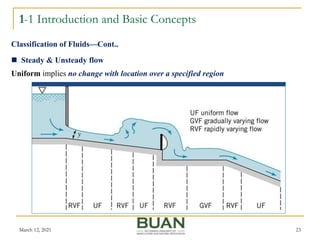

- Classifications of fluid flows such as internal vs. external, viscous vs. inviscid, and compressible vs. incompressible

- The no-slip condition and its implications for fluid behavior near surfaces