1 of 3 FIN 3302 – Exam I Review Fall 2017 Chapter 1.docx

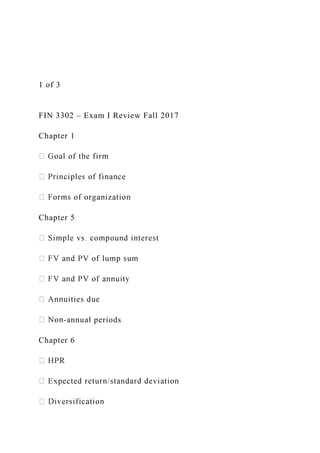

- 1. 1 of 3 FIN 3302 – Exam I Review Fall 2017 Chapter 1 Chapter 5 -annual periods Chapter 6

- 2. 2 of 3 Sample Questions 1) Which of the following goals of the firm are synonymous (equivalent) to the maximization of shareholder wealth? A) profit maximization B) risk minimization C) maximization of the total market value of the firm's common stock D) none of the above 2) You inherit $300,000 from your parents and want to use the money to supplement your retirement. You receive the money on your 65th birthday, the

- 3. day you retire. You want to withdraw equal amounts at the end of each of the next 20 years. What constant amount can you withdraw each year and have nothing remaining at the end of 20 years if you are earning 7% interest per year? A) $15,000 B) $28,318 C) $33,574 D) $39,113 3) The risk-free rate of interest is 4% and the market risk premium is 9%. Howard Corporation has a beta of 2.0, and last year generated a return of 16% with a standard deviation of returns of 27%. The required return on Howard Corporation stock is A) 36%. B) 34%. C) 26%. D) 22%.

- 4. 4) Today is your 21st birthday and your bank account balance is $25,000. Your account is earning 6.5% interest compounded monthly. How much will be in the account on your 50th birthday? A) $159,795 B) $162,183 C) $163,823 D) $164,631 5) All of the following statements about agency problems are true except: A) Agency problems interfere with the goal of maximizing shareholder value. B) Agency costs are paid by the managers who do not act in the shareholders' best interest. C) Agency problems result from the separation of management and the ownership of a firm. D) The root cause of agency problems is conflicts of interest.

- 5. 3 of 3 6) Which of the following conclusions would be true if you earn a higher rate of return on your investments? A) The greater the present value would be for any lump sum you would receive in the future. B) The lower the present value would be for any lump sum you would receive in the future. C) Your rate of return would not have any effect on the present value of any sum to be received in the future. D) The greater the present value would be for any annuity you would receive in the future. 7) Investment A has an expected return of 14% with a standard deviation of 4%, while

- 6. investment B has an expected return of 20% with a standard deviation of 9%. Therefore, A) a risk averse investor will definitely select investment A because the standard deviation is lower. B) a rational investor will pick investment B because the return adjusted for risk (20% - 9%) is higher than the return adjusted for risk for investment A ($14% - 4%). C) it is irrational for a risk-averse investor to select investment B because its standard deviation is more than twice as big as investment A's, but the return is not twice as big. D) rational investors could pick either A or B, depending on their level of risk aversion. 8) Joe purchased 800 shares of Robotics Stock at $3 per share on 1/1/15. He sold the shares on 12/31/15 for $3.45. Robotics stock has a beta of 1.9, the risk- free rate of return is 4%, and the market risk premium is 9%. Joe's holding period return is: A) 15.0%. B) 16.5%.

- 7. C) 17.6%. D) 21.1%. Key 1. C 2. B 3. D 4. C 5. B 6. B 7. D 8. A PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2017/Vol. 43/No. 5 213 I n August, our national news was filled with horrifying images of racism on display. If racism weren’t such a serious issue, seeing

- 8. people marching with Tiki torches might have almost seemed comical. The Nazi flags were chilling. It was quite the deadly show of visual, ver- bal, physical, and emotional hatred that I never thought I would ever see again in my country. Yet with this event and similar ones that followed, we have learned how deeply racism is imbedded in American culture. Following the rebuke from the United Nations on human rights (Gearan & Wang, 2017). Malik (2017) pointed out the following: It took only eight months to go from a nation that voted for a black president two terms in a row to one that is suffering from race riots and killings, with officials having to send troops out on to the streets and declare a state of emer- gency. The speed with which it happened is the clue that it was, in fact, happening all along, unseen. And the fact that it was lying in wait is an indicator of how little racial equality is prized in the United States’ DNA. Malik (2017) explains why ostensi- bly developed countries, once faced with adversity, a vacuum of authority, or questionable leadership, tend to

- 9. fall apart along the lines of race. In stable times of prosperity and rational leadership, “the promotion and en - shrining of the rights of the more vul- nerable is cosmetic at best, under- mined and papered over at worst. The foundations were there and contin- ued to be laid even during Obama’s leadership” (Malik, 2017). Such a sorry state of affairs. How does racism develop, what is its impact, and what can we do about it? The Development Of Racism Racism, a developed set of atti- tudes, includes antagonism based on the supposed superiority of one group or on the supposed inferiority of another group based solely on skin color or race (Beswick, 1990). No human being is born with racist, sex- ist, and other oppressive attitudes. Would children even notice differ- ences if no one said anything about them? Yes, they would, for the fol- lowing reasons (Rollins & Mahan, 2010, pp. 70-71): • Early on, children notice differ- ences and mentally organize these observations into categories. This is how young children make sense of their ever-expanding world.

- 10. • Attitudes about “us and them” are learned and reinforced in the home, school, and church, and through the media. • By 3 years of age, children have learned to categorize people into “good or bad” based on superficial traits, such as race or gender. • Children 2 years of age or younger learn names of colors, then begin to apply these names to skin color. • By 3 years of age or even earlier, children can show signs of being influenced by what they see and hear around them. They may even pick up and exhibit “pre-preju- dice” toward others based on race or disability. • Children 4 and 5 years of age may use racial reasons for refusing to interact with others who are dif- ferent from themselves; they may act uncomfortable around or even reject people with disabilities. • By the time children enter ele- mentary school, they may have developed prejudices. Stereotypes remain until personal experience or someone attempts to correct them.

- 11. Savard and Aragon (1989) tell us that parents are the earliest and most powerful source of racial attitudes (positive or negative); peers are a close second. Open-mindedness increases with age. The Impact of Racism On Health Gee, Walsemann, and Brondolo (2012) note studies that indicate racism may influence health inequities. Growing from infancy into old age, individuals encounter social institu- tions that may create new exposures to racial bias. Gee and colleagues (2012) view racism and health inequities from a life course perspective. They found that repeated exposure to moderate racial discrimination can cause illness after a time. Health can also be affected by social systems, such as education, the criminal justice system, and the labor market. Racism leads to housing and school segregation, limiting a per- son’s social network, and eventually, their employment opportunities and health. Over a lifetime, an individual who is subjected to racism has longer periods of unemployment or under- employment, incarceration, and/or illness. Compared to someone who has not experienced racism, someone who has may have a shorter career

- 12. and retirement period, and eventual- ly, a shorter life expectancy. Racism also has an impact on the health of those who migrate to a new country. Although newly arrived immigrants are reported to have bet- ter health than non-immigrants in North America, their health declines The Depth of Racism in the U.S.: What It Means for Children Judy A. Rollins, PhD, RN From the Editor 214 PEDIATRIC NURSING/September-October 2017/Vol. 43/No. 5 with increased length of stay. First attributed to the process of adapting to a new culture (sedentary North American lifestyle and increased intake of fatty food), research now indicates decline may be due to racism (Na, 2012). Ausdale and Feagin (2001) note that early childhood is a crucial sensi- tive period when stressors such as racial discrimination may have an impact on an individual’s long-term well-being, affecting brain develop-

- 13. ment and the formation of neutral connections between different regions. The brain and other parts of the body do not forget when bad things hap- pen in early life (Shonkoff, in Kuehn, 2014). In later years, children exposed to racial discrimination may perceive their own ethnic group negatively, become self-conscious, and develop low self-esteem and symptoms of depression (Na, 2012). Implications for Nursing Research suggests efforts nurses can take to help limit the effects of discrimination. Mossakowski (2003) found that the more strongly people identified with their own ethnic group, the less likely they were to dis- play symptoms of depression. This study showed that a stronger sense of ethnic identify meant having a sense of ethnic pride, being involved in eth- nic or cultural practices, and having knowledge about and commitment to the ethnic group. She concluded that ethnic identity not only directly pro- tects individuals from discrimination, but also buffers the stress of discrimi- nation on mental health. Nurses can support children’s eth- nic identify by learning as much as possible about the cultural back- grounds of the populations served by

- 14. their practice that are different from their own. They can encourage chil- dren’s pride and self-esteem through an eagerness and curiosity to learn about children’s cultural heritage from the children themselves. Healthcare facilities can use art and design to cel- ebrate the various cultures served to provide a sense of welcome and pride for those who receive treatment there. Nurses should keep apprised of the community’s political, social, racial, and other related issues that could have an impact on children and teens in their practice. Talking to children about discrimination is important for their health and development, and nurses should not avoid discussing the topic. Supporting research-based cur- ricula for children, such as Teaching Tolerance, can also be encouraged. Conducting parenting classes could prove helpful. Research findings indi- cate that parents’ responses to their own experiences of racial discrimina- tion can influence their parenting behaviors (Sanders-Phillips, Settles- Reaves, Walker, & Brownlow, 2009). Parents who have experienced greater racial discrimination may become less sensitive to their children’s needs and less able to display affection, fail to prepare them for how to cope with

- 15. discrimination, and use harsh disci- pline. At the same time, research tells us that more nurturing and involved parenting can weaken the adverse outcomes for youth associated with their own experience of discrimina- tion (Gibbons et al., 2010). We must never forget that whether it is visible or not, hate can be lurking just below the surface. As pediatric nurses, we can make a difference to diminishing racism and discrimina- tion in our daily interaction with patients and their families. References Ausdale, D.V., & Feagin, J.R. (2001). The first R: How children learn race and racism. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. Beswick, R. (1990). Racism in America’s schools. ERIC Digest Series, EA 49. Retrieved from https://www.ericdigests. org/pre-9215/racism.htm Gearan, A., & Wang, A (2017, August 16) In veiled criticism of Trump, U.N. chief says racism is ‘poisoning our societies.’ The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/ national-security/in-veiled-criticism-of- trump-un-chief-says-racism-is-poison-

- 16. ing-our-societies/2017/ 08/ 16/ ddd03984- 8 2 a 5 - 11 e 7 - a b 2 7 - 1 a 2 1 a 8 e 0 0 6 a b _ story.html?utm_term=.962893eebdfe Gee, G.C., Walsemann, K.M., & Brondolo, E. (2012). A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequal- ities. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 967-974. Gibbons, F.X., Etcheverry, P.E., Stock, M.L., Gerrard, M., Weng, C., Kiviniemi, M., & O’Hara, R.E. (2010). Exploring the link between racial discrimination and sub- stance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 785-801. Kuehn, B. (2014). AAP: Toxic stress threat- ens kids’ long-term health. JAMA, 312(6), 585-586. Malik, N. (2017, August 25). After a UN warn- ing over racism, America’s self-image begins to crack. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/com- mentisfree/2017/aug/25/un-warns-us- racism-but-trump-era-bigotry-not-blip- charlottesville Mossakowski, K. (2003). Coping with per- ceived discrimination: Does ethnic iden- tity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 318- 331.

- 17. Na, L. (2012). Children and racism: The long- term impact. Retrieved from http:// www.aboutkidshealth.ca/En/News/ NewsAndFeatures/Pages/children- racism-long-term-impacts.aspx Rollins, J., & Mahan, C. (2010). From artist to artist in residence: Preparing artists to work in pediatric healthcare settings. Washington, DC: Rollins & Associates. Sanders-Phillips, K., Settles-Reaves, B., Walker, D., & Brownlow, J. (2009). Social inequality and racial discrimina- tion: Risk factors for health disparities in children of color. Pediatrics, 124(3), S176-S186. Savard, W.G., & Aragon, A. (1989). Racial Justice Survey Final Report. Portland, OR: Northwest Regional Educational Laboratory. Copyright of Pediatric Nursing is the property of Jannetti Publications, Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

- 18. Racism’s Uprooting White Racial Jeopardy and Democracy To show what is beneficial, what is obligatory, what is good — that is the task of education. Education concerns itself w ith the motives for effective action. For no action is ever carried out in the absence of motives capable of supplying the indispensable amount of energy for its execution. — Simone Weil, The Need for Roots 14 5 B LA C K R E N A IS S

- 19. A N C E N O IR E To varying degrees, the approaches used to teach anti-racism fall short of their intended goals, because of the tacit belief that non-Whites alone are harmed by racism, while Whites reap only its benefits. This perspective is at odds with, and unable to fully capture, many aspects o f our national history and o f our current reality. It cannot, for example, account for the race-induced political behavior o f poor and working-class Whites. For several decades now, that behavior has shown itself to be pointedly self-endangering, culminating with the election o f Donald J. Trump to succeed President Barack Obama. The anguished spectacle o f poor and

- 20. working-class Whites vacating their economic and medical (self-)interest in order to conform to race-induced opposition to the pejoratively renamed “Obamacare,” while pleading for (the continuance of) Affordable Care, is revealing. It indicates that for many, racism has destroyed the ability to define, assert, or defend their own survival interests. Despite numerous similar inconsistencies, the traditional designation o f victims and beneficiaries remains unchanged, perhaps, because it is consistent with racism’s definition o f the powerless and the powerful. Insights on the psychology of oppression developed by the twentieth century French philosopher Simone Weil offer a way out o f this impasse. Weil’s analysis provides an urgently needed framework for re-examining racism, one that allows for a more complex understanding o f the ways in which people with W hite racial privilege are endangered by that privilege. In the collection o f essays translated and published posthumously as The N eed fo r Roots: Prelude to a Declaration o f Duties towards M ankind, Weil declares that “To be rooted is perhaps the most im portant and least recognized need o f the hum an soul” (Weil 1978, 41). After describing the familial and social structures through

- 21. which individuals are “rooted” so as to achieve moral, intellectual, and spiritual stability, Weil examines factors contributing to its opposite, what she calls “uprootedness.” Because she is writing during the Second World War, Weil focuses on contemporary causes o f uprootedness, such as military conquest and colonialism. W hile she does not mention racism as a cause o f uprootedness, numerous studies have confirmed racisms uprooting effects, most notably the doll studies developed by Kenneth Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark that were used in the Brown v. Board o f Education case to end state-sponsored school segregation in the 1950s.' Contrary to expectations of preference based on “similarity bias,” the Black children in the Clark study showed a distinct preference for and favorable view o f W hite dolls and a marked rejection o f the Black dolls with which they nevertheless identified. I will return to this point later in the essay, as I examine the “narrative relationships” deployed to destroy self-image and self-esteem, and — in the process — generate a negative “similarity bias.” Suffice it to say, Weil’s description o f uprootedness as a “self-propagating” social disorder illuminates one o f the least understood, least examined aspects

- 22. o f the ideology o f race — its injurious psychological, and perhaps neural, impact on individuals and groups positioned to internalize, act out, and ostensibly, benefit from its suggestions. As she observes, “Uprootedness is by far the most dangerous malady to which hum an societies are exposed, for it is a self-propagating one__ Whoever is uprooted himself uproots others. Whoever is rooted himself doesn’t uproot others” (Weil 1978, 45). Weil’s analysis makes clear that racism’s uprooting o f Blacks and other racial minorities is inevitably the secondary effect o f racism’s uprooting o f Whites, a latent source o fW h ite racial jeopardy. That is to say, the ideology o f race must first have destroyed or dismantled certain vital hum an capacities within the W hite population, as an absolute pre-condition for the sustained violence o f racism. O f these capacities, perhaps the most im portant is the cognitive capacity to perceive non-W hite people’s equal humanity. Examining racism through the lenses provided by Weil’s analysis, new questions emerge. Exactly how are W hite people “uprooted” by racism? How is uprooting manifested or displayed? W hat are its psychological contours? And given the new developments in neuroscience research, can we go beyond a psychological

- 23. mapping to identify the neural correlates o f racism? M ost importantly, given the long history during which it has remained undiagnosed and untreated, what are the long-term consequences o f racisms uprooting o f Whites? RE-EXAMINING RACISM’S DIVIDE In the following discussion, I attem pt to answer these questions by looking first at the pitfalls o f mainstream understandings and approaches to anti-racism and by applying recent developments in neuroscience research to expose racism and W hite privilege as dangers to W hites and, ultimately, to u.s. democracy. I argue that a more efficacious design of anti-racist education can only come from a comprehensive understanding o f the jeopardy we all face from racism’s uprooting effects. For W hites, racism and W hite privilege threaten those competencies that enable and sustain healthy social interactions, professional performance, and democratic praxis in a multiracial society, namely, effective moral reasoning, moral decision-making, historical thinking, social literacy, and their prerequisites — emotional engagement and narrative knowledge.

- 24. W ith few exceptions, scholarly analyses o f racism are shaped by binary assumptions about its impact: Whites reap the benefit o f W hite privilege, while Native Americans, African Americans, Latinos, Asians, Muslims2, and others are harmed by it. W hen injury to W hites is mentioned, it is generally no more significant than the harm o f a guilty conscience. In the best-seller Why Are A ll the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? A n d Other Conversations About Race, psychologist Beverly Tatum recounts an exchange with a student that underscores the shortcomings o f most current approaches to anti-racism. In examining “The Cost o f Racism,” Tatum describes a W hite male student who, after completing her psychology o f racism course, confessed that he “now understood in a way he never had before just how advantaged he was” (Tatum 1997,13) because o f racism. The student also shared that “he didn’t think he would do anything to try to change the situation. After all, the system was working in his favor” (Tatum 1997,13). After noting that this response was an anomaly, Tatum goes on to say that it, nevertheless, raised two im portant questions: “W hy should Whites who

- 25. are advantaged by racism want to end that system o f advantage? [And] W hat are the costs o f that system to them?” (Tatum 1997,13). Tatum answers first with a financial accounting o f what racism costs the u.s. economy, citing a 1989 article, “Race and Money,” that appeared in Money magazine. After furnishing anecdotal evidence o f emotional loss suffered by W hite women and men, Tatum asserts: “W hite people are paying a significant price for the system o f advantage. The cost is not as high for W hites as it is for people o f color, but a price is being paid” (Tatum 1997,14). Since I first read Tatum’s account of her W hite male student’s response and o f the questions it prom pted, I have remained fascinated by both. I am fascinated by the student’s response because, it supplies language for what I believe is a widely held view: that when W hite people commit to anti-racism, they are acting against their own rational self-interest or are doing so as an expression o f goodwill toward Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans, Muslims, and others who are disadvantaged by race and racism. The suggestion that racism is a threat to Whites, that they too are in danger o f being uprooted by it, is still a novel one.

- 26. I am fascinated by Tatum’s response because she never poses what I view as the more urgent questions: why did her student not recognize what the system was costing him? And how might she and other anti-racist educators be preventing this discovery in their legitimate focus on defining racism as a system o f advantage and disadvantage? W hile she does not address these questions, Tatum’s analysis does illustrate just how the myth o f W hite people’s imm unity to racism’s uprooting is perpetuated. In discussing how institutional racism hurt the u.s. economy and, thereby, W hite Americans, she mentions only those experiences o f economic harm that people disadvantaged by race experience, namely, “real estate equity lost through housing discrimination, or the tax revenue lost in underemployed communities o f color, or the high cost o f warehousing hum an talent in prison” (Tatum 1997,14). Here, Tatum 14 7 B LA C K R

- 27. E N A IS S A N C E N O IR E suggests that the economic, social, and psychological injuries sustained by communities o f color am ount to a cost to the economy as a whole, which is the only measure o f (economic) cost to Whites. To the extent that there is only a collective — and not an individualized — economic cost for Whites, it must mean that relinquishing W hite privilege or (with more difficulty) overcoming racism can only be a gesture of goodwill or economic patriotism, not one o f self-preservation or self-interest on the part o f W hite

- 28. individuals. Peggy M cIntosh’s widely respected essay, “W hite Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” (1989), provides further insight into the mythology of W hite people’s im m unity to racism’s uprooting effects. The essay opens with an epigraph in which McIntosh confesses, “I was taught to see racism only in individual acts o f meanness, not in invisible systems conferring dominance on my group.” The catalogue that follows is McIntosh’s attempt to delineate this “invisible system.” In listing what she calls the “Daily Effects o f W hite Privilege,” McIntosh does n ot include a single injury that might accompany the many “privileges” she identifies. In fact, the list displays a peculiar lack o f reflection on, and lack o f interest in, the harmful effects o f W hite privilege. McIntosh is able to avoid this discovery by a steadfast refusal to expose or identify the hum an agents implicated in the privileges she enumerates. Putting the spotlight on these persons, two details stand out. First, hatred and/or meanness cannot account for the spectrum of attitudes and actions she describes. Second, the persons dispensing or otherwise responsible for the privileges she enjoys have, to varying degrees, been (psychologically and morally) uprooted.

- 29. Among the mundane examples o f W hite racial privilege McIntosh pulls out o f her invisible knapsack is the following: “I can go shopping alone most o f the time, pretty well assured that I will not be followed or harassed” (#4).3 The store clerk who does not follow McIntosh but who peeps at me through the fitting room door is not mean, does not hate me. Disabling narrative relationships — with non-W hite characters in television, cinematic, historical, and other narratives — have triggered emotions o f suspicion and impaired her ability to see me. Uprooted by racism, what she sees instead is a Black-female-and- therefore-shoplifter. Favorable narrative relationships with W hite characters have also blunted her ability to discern crime in White-face. So while she follows me around in a harassing performance o f helpfulness, the real shoplifter menaces the merchandise. Read carefully, one discovers that the privileges in McIntosh’s invisible knapsack have been stacked by “invisible” people psychologically and morally disabled by racism’s uprooting, people whose ability to accurately interpret human behaviors and motives have likewise been impaired. Her composition o f such a comprehensive listing o f assumed

- 30. privileges can only mean that McIntosh knows the stackers, has seen or has been one o f them. If she had seriously analyzed the type o f impairment their actions or attitudes reflect, privilege #15 — and perhaps the entire essay — would have been framed differently. Instead o f simply asserting, "I do not have to educate my children to be aware o f systemic racism for their own daily physical protection,”4 McIntosh would have added, “But I do have to educate my children to be aware o f the daily threat racism and W hite privilege pose to their psychological, intellectual, and moral health.” Two defects weaken McIntosh’s anti-racist methodology: first, not identifying the people responsible for the racial privileges she enumerates, and second, not analyzing the full range of psychological dispositions involved in its operation. These defects also appear in the structural racism model championed by legal scholar John A. Powell, former director o f the Kirwan Institute for the Study o f Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University. In “Structural Racism: Building upon the Insights o f John Calmore,” Powell asserts that “Racism need not be either intentional or individualist. Institutional practices and cultural patterns can perpetuate racial inequity

- 31. w ithout relying on racist actors” (795). Contrasting institutional and structural racism, Powell notes: The institutional racism framework reflects a broader recognition o f the forms through which racialized power is deployed, dispersed, and entrenched. However, while illustrating the ways in which racism is often non-individualist and non-intentionalist, this framework focuses too heavily on intra-institutional dynamics, and thus fails to account for the ways in which the joint operations o f social institutions produce critical racialized outcomes. [...] Structural racism shifts our attention from the single, intra-institutional setting to inter-institutional arrangements and interactions. (795-796) As an intersectional approach, Powell’s structural racism model provides a means o f both identifying and countering the structures of compounding jeopardy that constrict

- 32. opportunities for poor African American, Latino, Native American, and other non-W hite communities. However, in simultaneously reducing the m ultitude o f racist dispositions to the single stereotypical mindset o f “bad actors” and substituting a focus on residual effects o f presumably abandoned mechanics, the structural racism model moves the discourse from one shaky leg to another. The notion that structures can maintain a racist disposition and continue to produce racist outcomes w ithout the involvement o f racist hum an agents or that institutions do not reflect the vision or mindset o f the people by whom they are governed is simply not credible. Recent events involving the three branches of our own democratic government are instructive. O n the one hand, the machinations o f the executive branch demonstrate that if and when operated by individuals with an autocratic vision (or personality) democratic structures will not continue to support democratic practices or policies, or produce democratic outcomes. O n the other hand, recent rulings from the federal bench regarding the Trump administrations Muslim ban indicate that only when structures are governed by human agents committed to a democratic vision can

- 33. democratic outcomes be assured. The same is true o f racism. As such, an approach that combines the critique o f structural racism with an examination o f hum an agents involved in its continuance would be anchored by two legs and ensure analytical symmetry. The discomfort underlying the refusal to expose hum an beings involved in the practice o f racism stems from an ahistorical and simplistic equation o f racism with hatred or meanness, as McIntosh admits to having been taught. Recalling Tatums W hite male student, however, it is clear that his resolution to preserve racism and, inevitably, to become a self-consciously racist agent was undertaken, one might say, “with malice toward none.” Nevertheless, defining racism solely as a system o f advantage to Whites creates several significant impediments to anti-racist education. First, this definition supports a senseless and binary positioning of W hite “donors” and non-W hite “debtors,” with opposing stakes. Second, it simultaneously and paradoxically entreats W hite “donors” to relinquish certain modes o f racism as a benefit to others and not on behalf

- 34. o f their own psychological, intellectual, and ethical growth or liberation. Third, in so doing, it replicates the structure o f international relations in the post-colonial era where formerly colonized nations are defined as debtors and those former imperial powers enriched by the colonial enterprise are defined as donors. Fourth, it prevents, or else discourages, W hite people from acknowledging their own uprootedness, since doing so carries an automatic indictm ent for moral failure. Fifth, it prevents people with race-based privilege from discovering how they too are endangered by structures of thinking and structures of feeling that directly and indirectly endorse hierarchical distributions o f hum an worth and rights. Sixth, it fails to reveal the dangers and dispel the potential envy of a self-endangering racial privilege. Seventh, it fails to fully interpret the significance and value o f the intellectual, psychological, ethical, spiritual, and material resourcefulness manifested in African American, Asian, Latino, Native American and various non-

- 35. Western cultural traditions and histories. In sum, the view o f racism as solely or primarily a system o f W hite racial advantage fails to adequately empower or motivate W hite, Asian, Native American, Latino, African American, and other non-W hite communities for the collaborative task o f ending racism. The misconception that W hite people are not individually harmed by racism, that it is not a threat to them, inhibits the mass com m itm ent and participation needed to effectively counter racisms uprooting. 14 9 B LA C K R EN A IS SA N C E

- 36. N O IR E R S D : R A C I S M S P E C T R U M D I S O R D E R A key reason for W hite people’s seeming lack o f concern for their own racial jeopardy is the assumption that racism is a moral defect and that having a sufficient moral foundation confers immunity. Numerous historical examples, however, amply demonstrate that having an extensive moral foundation is no defense against racist indoctrination. Recall that despite being versed in the moral teachings o f the New Testament that include instructions to love your neighbor as yourself and to treat others as you would like to be treated, the earliest European arrivants to the Americas were unable to resist racist conscription. In tracing the history o f legislative violence in seventeenth-century Virginia from which race and racism ensued, political scientist Joel Olson notes that “Race as we now know it did n ot exist when the first colonists

- 37. landed on the shores o f the New W orld” (Olson 2001,165). Racism, Olson asserts, “was a deliberate, public, conscious policy o f the Virginia ruling elite” (Olson 2001,167) invented to preempt cross-racial economic and political alliances. In the article titled “The Democratic Problem o f the W hite Citizen,” Olson recounts, Through a series o f acts from r670 to 1705, the Virginia assembly made laws distinguishing African and Indians from Europeans. They forbade Africans and Indians to own Christian servants and the legal definition o f “Christian” now excluded baptized African and Native Americans... Through various legislative measures and social pressures Virginia elites simultaneously fastened Africans to a lifetime, hereditary, degraded status and created a new group of relatively privileged people heretofore unknown in hum an history. Remarkably, these measures amassed rich and poor, planter and servant, esteemed and lowly into a single group unified not by

- 38. ancestry but by the right to own property (including hum an property), the right to share in the public business, and a pledge to ensure the degraded position o f all those defined as black. (Olson 2001, 166-168) W hile the legislative acts that engineered racism and W hite racial privilege equalized the social status of all those defined as “W hite,” it did not equalize the economic and political interests o f poor W hites and the ruling (White) elite. That is to say, although the social identities o f W hite workers improved, their economic interests were neither aligned with nor prioritized by the ruling elite. In acquiescing to this new regime, therefore, poor W hites sacrificed their economic and political self-interest for the mostly symbolic “wages o f Whiteness.” In systematically discrediting the image o f non-Whites and enlisting the participation o f poor W hites in this project, the ruling elite launched a two-pronged psychological assault on non-Whites and on poor Whites. By assimilating to this new racialized self-definition, poor English workers — and later Irish, Italian, German, Polish, and other ethnic Europeans in the u.s. — relinquished their

- 39. cultural distinctiveness, class-specific epistemological standpoint, and interpretive autonomy. Their acculturation to the illusion o f dominance shared with the ruling elite was the first indication o f racism’s ability to uproot, to impair intellectual agency and interpretive competence. In effect, W hite racial privilege was the nation’s first designer drug, consuming vital capacities — intellectual, psychological, moral — with every thrilling intake. The “pledge” among W hites to “ensure the degraded position” o f all those defined as non-W hite would find expression and fulfillment through narrative acts and the re-configuration o f “empathic bias.” This would involve scripting negative narrative relationships toward non-Whites and positive narrative relationships toward Whites sufficient to overshadow the empathic biases that would otherwise have evolved from their lived interactions and moral commitments. From the outset, therefore, racism was a psychological, not a moral, disorder dependent on a conditioned emotional detachment. W hile this detachment and resulting disorder can have moral effects and/or implications, the disorder is itself psychological with

- 40. perhaps identifiable neural correlates. As a psycho-social spectrum disorder, racism stems from an involuntary and symmetrical blindness to one’s own and to other people’s human worth. It involves both conditioned emotional detachment and hyper attachment and produces disparate forms o f impairment and disability. From its foundational measurement o f hum an worth, racism establishes other “race”-based measurements o f hum an capacities, human achievements, hum an potential, human rights, and hum an responses. W hile racism’s blindness is typically assumed to manifest itself in attitudes and acts o f hatred or meanness, these are merely points on the racism spectrum. The socialized blindness that undergirds racism can manifest in a broad spectrum o f attitudes and actions, involving varying degrees o f emotional detachment or hyper-attachment towards persons positioned at various tiers on the hierarchy o f human worth and entitlement posited by the ideology o f race. Attitudes and actions toward persons positioned at or near the bottom o f the hierarchy o f hum an worth include, but are not limited to: suspicion, fear, unwarranted and frequently

- 41. self-endangering mistrust, disinterest, apathy, a lack o f concern for actual and potential danger or injury to such persons, sexual attraction, curiosity, envy, a desire to help or rescue, a lack o f self-restraint or gentleness towards such persons, indifference or permissiveness about abuse towards such persons — a spectrum o f psychological dispositions conditioned by emotional detachment. Attitudes and actions toward persons positioned at or near the top of the hierarchy, and that constitute W hite racial privilege, include but are not limited to: feelings o f comfort, interestedness, empathy, unwarranted and frequently self-endangering trust, feelings o f concern and distress at real or imagined danger or injury to such persons, a sense o f the greater value, greater relevance o f their roles and contributions — a spectrum of psychological responses conditioned by hyper-attachment. As a psycho-social spectrum disorder, racism also involves a socialized blindness to the structures through which hierarchical distributions o f advantage, opportunity, immunity, and material resources are made. As such, it self-propagates through a concurrent blindness to its own operation, an effect with considerable strategic

- 42. significance. As Wahneema Lubiano has observed, it allows W hite people to see themselves as acting morally when, according to their own moral tenets, they are not.5 The tendency to self-propagate, as Weil emphasizes, is precisely what makes uprootedness (through W hite racial privilege) “the most dangerous malady to which hum an societies are exposed” (Weil 1978, 45). The stark contrast between policy responses that criminalized the mostly African American and Latino crack addicts in the 1980s and 1990s and the policy responses seeking therapeutic options for todays mostly W hite heroin addicts is noteworthy. It attests to the differing degrees of emotional attachment to persons situated at different tiers on the hierarchy of hum an worth posited by the ideology o f race. If racism had not created an emotional detachment toward non-White people, politicians and policy-makers would not have been uprooted by this socialization and would have experienced feelings of concern, if not alarm, at the loss o f life among crack addicts. W ith feelings and emotion intact, they would have been able to exercise the type o f moral reasoning that would have provided a basis for acquiring “narrative

- 43. knowledge” — to be discussed hereafter — in the quest for appropriate policy responses. If emotional detachment had not impaired policy makers’ ability to formulate effective moral judgm ent about the addicts o f the late twentieth century, the therapeutic solutions now being pursued would have been proposed then. Lives would have been saved then and, with structures already in place, lives would be saved now. 15 1 B LA CK R EN A IS SA N C E NO IR

- 44. E EXPOSING THE NEUROSCIENCE OF RACISM Emotional detachment toward non-Whites is the foundation — and catalyst — for a vast structure of dystopian feeling toward the poor, prison inmates, the homeless, immigrants, low-wage workers, people with intellectual disabilities, and other groups defined as disposable. The broad spectrum o f impairment and disability resulting from the emotional detachment conditioned by racism becomes especially significant when viewed in relation to the work o f the renowned neuropsychologist Antonio Damasio on the role o f emotion and feeling in moral judgment. In presenting to the public his clinical findings that “certain aspects o f the process o f emotion and feeling are indispensable for rationality” (xiii) and “that the absence o f emotion and feeling is no less damaging” than emotional biases (xii), Damasio mentioned first his own cultural socialization with regard to rational decision-making. In Descartes’ Error (1994), Damasio writes,

- 45. I had been advised early in life that sound decisions came from a cool head, that emotions and reason did not mix any more than oil and water. I had grown up accustomed to thinking that the mechanisms o f reason existed in a separate province o f the m ind, where emotion should not be allowed to intrude, and when I thought o f the brain behind the m ind, I envisioned separate neural systems for reason and emotion, (xi) The case that prom pted Damasio to re-think the role o f emotions and feeling in effective decision-making was that o f a patient who “had had an entirely healthy m ind until a neurological disease ravaged a specific sector o f his brain” causing a “profound defect in decision-making” (xii). According to Damasio, The instruments usually considered necessary and sufficient for rational behavior were intact in him. He had the requisite knowledge, attention, and memory; his language was flawless; he

- 46. could perform calculations; he could tackle the logic o f an abstract problem. There was only one significant accompaniment to his decision-making failure: a marked alteration o f the ability to experience feelings. Flawed reason and impaired feelings stood out together as the consequences o f a specific brain lesion, and this correlation suggested to me that feeling was an integral component o f the machinery o f reason. Two decades o f clinical and experimental work with a large num ber o f neurological patients have allowed me to replicate this observation many times, and to turn a clue into a testable hypothesis. (xii) (Emphasis added.) In the years since its initial publication, several studies have confirmed Damasio’s “testable hypothesis.”6 Among other effects, these findings call into question the preferred formula for effective decision-making — one that excludes emotion and feeling — that has been disseminated and established as a requisite guideline in almost every arena o f public, professional, and personal decision-making from the law

- 47. and law enforcement, to business, international relations, politics, economics, diplomacy, medicine, journalism, education, sports, marriage, and family life. Given the pervasive influence o f Descartes’ cogito on Western culture and its widespread cultural diffusion as a decision-making protocol, the neuroscience research confirming the essential role o f emotion and feeling in moral decision-making raises new questions. Has the cogito already “marked” what Western researchers view as a healthy/integrated brain? Can “impaired feelings” be caused by factors other than disease or physical injury to the brain? Can socialization, for example, impair or deactivate the brain’s emotional circuits? Can the gender socialization that males in particular receive about the incompatibility o f emotion and reason produce neural effects and a similar impairment o f feelings as those caused by injury or disease? Can race or gender socialization deactivate emotional systems o f the brain in general or with regard to specific stimuli? Conversely, are there deficits in neural processing in a healthy — non diseased, uninjured — brain that can be attributed — broadly speaking — to cultural socialization? Or, to p ut it succinctly, is socialized

- 48. brain injury possible? W hat is the role o f emotion and feeling in public policy decision-making? To what extent might defective public policy decision-making be attributable to emotional detachment toward dispossessed and disposable constituencies? To the extent that emotion is essential to moral reasoning, how might emotional detachment affect historical thinking, social literacy, and the practice o f democracy, all of which involve moral reasoning? O f the many studies inspired by Damasio’s clinical findings, one o f the most instructive is a 2001 study by an interdisciplinary team o f investigators lead by Harvard professor Joshua Greene, at the time a doctoral student in Princeton’s Philosophy department. In the article “An fMRI Investigation o f Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment,” Greene and his colleagues describe using functional magnetic resonance imaging — fMRI — to observe the neural activity o f test subjects faced with a variety o f decision-making scenarios involving “moral-personal conditions,” “moral-impersonal conditions,” and “non-moral conditions.”7 The study focused on two moral dilemmas representing moral-impersonal and moral-personal

- 49. conditions, respectively. O ne involved a runaway trolley, the other a footbridge. As they describe the two dilemmas, A runaway trolley is headed for five people who will be killed if it proceeds on its present course. The only way to save them is to hit a switch that will turn the trolley onto an alternate set o f tracks where it will kill one person instead o f five.... [In] a similar problem, the footbridge dilem m a... a trolley threatens to kill five people. You are standing next to a large stranger on a footbridge that spans the tracks, in between the oncoming trolley and the five people. In this scenario, the only way to save the five people is to push this stranger off the bridge, onto the tracks below. He will die if you do this, but his body will stop the trolley from reaching the others. (2105) The researchers predicted the absence o f what they called “emotional interference” for responses to the impersonal trolley dilemma, as measured by both neural activity and

- 50. faster response times. As expected, Greene and his colleagues found that most respondents said yes to re-directing the trolley onto an alternate track in the first (moral-impersonal) dilemma, while most respondents said no to pushing a stranger off the footbridge in the second (moral-personal) dilemma. They concluded that, .. .from a psychological point o f view, the crucial difference between the trolley dilemma and the footbridge dilemma lies in the latter’s tendency to engage people’s emotions in a way the former does not. The thought o f pushing someone to his death is, we propose, more emotionally salient than the thought o f hitting a switch that will cause a trolley to produce similar consequences, and it is this emotional response that accounts for people’s tendency to treat these cases differently. (2106) [Emphasis added.] Although not its intended objective, the Greene study offers a preliminary basis for speculating about the ways in which a particular socialization — whether shaped by race or any other ideology — might lead to the

- 51. type o f emotional detachment that prevents the neurological engagement and activity essential for healthy decision-making about other people’s lives. This is im portant because racially-informed responses, misreadings, behaviors, and actions toward non-Whites are in some senses an accumulation o f emotionally detached (mis)judgments. Looking closely at the study, one notices that the “impersonal” character or framing o f the trolley dilemma seems to rest upon the social identities o f the people on the track and the empathic ability o f particular respondents, n o t on the dilemma itself. This can easily be illustrated by re-framing the dilemma, re-imagining the unknown person on the alternate track, and allowing that person to attain the same hum an distinction as the stranger on the footbridge whom test subjects have to touch. W ould test subjects be as emotionally detached in reasoning about the runaway trolley scenario if the person on the alternate track were an acquaintance — whether liked or disliked? Would they be as emotionally disengaged if the five were five Mexicans crossing the border illegally and the one were a u.s. border patrol agent? O r if the “trolley” were a grenade misfired from a u.s. military launcher and the five were five Afghan

- 52. civilians and the one were a u.s. soldier? 15 3 B LA C K R EN A IS SA N C E NO IR E RE-VIEWING RACISM AS A THREAT TO DEMOCRACY My point here is not to suggest that under these different (narrative) frames test subjects in the u.s. would make

- 53. different judgments and require longer response times in resolving the trolley dilemma, although this seems highly probable. Rather, my point is that to the extent that the variations suggested above elicit a more intense emotional engagement, they also reveal the social invisibility and/or disposability of the person on the alternate track and the resulting detachment with which test subjects were likely to have engaged the dilemma. Since social identities are charged — positively and negatively — with different emotional valences, moral judgm ent about those lives will inevitably be influenced and perhaps determined by these pre-set valences. These judgments are particularly fraught in professional and public policy deliberations. Re-examining the results o f the Greene study, the researchers seem to have overlooked one o f the most salient discoveries o f their own research: the neural similarity displayed between moral-impersonal and non-moral decision-making. If emotions are essential to moral reasoning, the observed non-involvement o f test subjects’ emotions in the trolley dilemma, as measured by neural activity and faster response times, would suggest that these decisions are neurologically defective. Thus, the researchers’ tacit acceptance o f this defect, their failure

- 54. to read these responses as defective, is perhaps indicative o f persistent cultural assumptions — and misconceptions — about the limited utility o f emotions. Their reference to, and perhaps preference for, the absence o f “emotional interference” is revealing. If the neural and behavioral responses to the moral-impersonal trolley dilemma in the Greene study are (socio-culturally) representative, they may indicate a significant pattern o f emotional disengagement in moral-impersonal decision-making about socially invisible “strangers,” the type o f decision-making voters in a democratic society must routinely perform. This finding that neural responses to “moral-impersonal” and “non-moral” dilemmas involve similar types o f emotional disengagement is particularly troubling since professional and public policy decision-making tends to occur in situations that resemble the conditions o f moral-impersonal decision-making in which the people at risk on policy-making “trolley tracks” remain invisible. It should be obvious that an adult citizen ought n ot to approach — or (neurologically) experience — the choice o f whether or not to fund at-home healthcare options for people with disabilities (a moral-impersonal dilemma) in the

- 55. same way as deciding whether to take the 6 p.m. or 7 p.m. flight from Washington, D C back to Kentucky or Wisconsin (a non-moral dilemma). And yet, this appears to be happening in the Congress on a daily basis. The Greene’s study and its overlooked implications provide a basis for theorizing about the neurological jeopardies underlying the intellectual habits that attend W hite racial privilege and their inevitable impact on the range o f decision-making responsibilities accompanying democratic participation and professional practice in a multi-racial society. Most discussions o f racism as a threat to democracy focus on the cliched assertion that, as an impediment to national reconciliation, it prevents u.s. Americans from achieving “a more perfect union.” W hile accurate, this summary view overlooks and overshadows the more consequential ways in which racism and W hite racial privilege jeopardize u.s. democracy by fostering inept historical thinking, social illiteracy, defective moral reasoning, defective (public policy) decision-making, and self-endangering voting behaviors. In large measure, these effects stem from the narrative relationships that precede and that are the blueprint for social interactions.

- 56. Analyses o f the ways as prompts for racism tend to focus on the proliferation o f racist images and characterization. To fully understand racism as a psychological spectrum disorder, however, one must examine the emotional quality o f narrative relationships engineered through the distorted representations o f non-White and W hite peoples in historical, literary, theological, cinematic, and other narratives. Specifically, one must understand the ways in which narrative relationships function as both emotional guides and emotional triggers. Racism operates through distorted narrative relationships that undermine both narrative knowledge and social literacy. “Narrative knowledge” is the term used by narrative medicine pioneer and medical educator, Dr. Rita Charon, to describe a set o f critical competencies instilled by literary reading. In Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories o f Illness (200 6), Dr. Charon, an internal medicine specialist who later impaired by a long history o f racist earned a Ph.D. in English, notes that socialization. If narratives are stories that have a teller, a listener, a time

- 57. course, a plot, and a point, then narrative knowledge is what we naturally use to make sense o f them. Narrative knowledge provides one person with a rich, resonant grasp o f another persons situation as it unfolds in time, whether in such texts as novels, newspaper stories, movies, and scripture or in such life settings as courtrooms, battlefields, marriages, and illnesses. (9)® As a key com ponent o f narrative medicine, narrative knowledge is envisioned as a remedy to a medical education process that many believe produces doctors with tremendous technical skills but who “lack the hum an capacities to recognize the plights o f their patients, to extend empathy toward those who suffer, and to join honestly and courageously with patients in their struggles toward recovery, with chronic illness, or in facing death” (3). In designing narrative medicine as a response to these deficits, Charon and other narrative medicine theorists recognized that “[u]sing narrative knowledge enables a person to understand the plight o f another by participating in his or her story with complex skills o f imagination, interpretation, and recognition” (9-10).

- 58. It is my belief that the narrative knowledge supporting both interpretive and ethical competence in medical practice is equally im portant to rehabilitating the range o f social and professional interactions that have been In the article titled “How Narrative Relationships Overcome Empathic Bias,” literary scholar Mary-Catherine Harrison makes the case for narrative relationships as an empathy generator based on the claim that they can overcome the limitation of being tied to similarity bias — that is, the notion that people are more likely to empathize with those they view as similar to themselves. As she sees it, narrative relationships formed with fictional characters, especially in literature and cinema, can be an im portant mechanism for generating empathy by circumventing the similarity bias that is alleged to be normative. In presenting her argument, Harrison first outlines the normative parameters o f narrative relationships, similarity bias, and empathic bias, citing several studies that corroborate the association o f similarity bias with empathy, that confirm the importance o f empathy as a precursor to “helping behaviors,” and that associate the lack o f empathy with “psychopathy, criminality, aggression, and anti-social behavior” (256).9

- 59. O ne pronounced omission in the studies Harrison mentions is a lack of attention to the ways in which racial narratives, since the seventeenth century, have re-ordered the importance o f race-based similarity and, thereby, re-configured the experience o f empathy.10 Recall that the experiences and preferences o f Black children in the Clark study did not conform to expectations o f preference/empathy based on similarity bias. If, as Harrison and other narrative theorists assert, narrative relationships can be a vehicle for overcoming similarity bias and generating empathy for people who don’t share prom inent social characteristics, it must be the case that narrative relationships o f a different sort were first used to construct and cultivate (racialized) similarity bias as a basis for empathy. Re-visiting the seventeenth century legislative acts used to craft race and racism, it is clear that these alone could n ot have generated the widespread emotional detachment toward non-W hite peoples and the hyper-attachment toward Whites. Narrative relationships were and are a vital mechanism for producing this outcome. Reverse sequencing from contemporary understandings of

- 60. narrative relationships, empathy, and similarity bias, it is easy to see how Whites and non-W hites must have been uprooted by the narratives relationships with characters that peopled the W hite supremacist narratives in literature, law, science, theology, and cinema in the centuries and decades before the social transformations o f the Civil Rights era. Long before the narrative transformations o f the Black Arts Movement and related developments in the publishing industry enabling the distribution o f literary works by non-W hite writers, before curricular expansions prom pted by the demands o f Black college students in the 1960s, dominant cultural narratives constricted empathic parameters throughout the society. In The Bluest Eye, for example, Toni Morrison depicts how Pauline Breedlove’s positive narrative relationships with W hite characters in 1940s cinematic narratives overshadow her negative social interactions with 15 5 B LA C K

- 61. R E N A IS S A N C E N O IR E hostile and/or racist Whites and produce a positive empathic bias toward them. This positive empathic bias generates caring behaviors toward her employers W hite daughter and a concurrent negative empathic bias toward and progressive emotional detachment from her own children. W ith no similarity bias to overcome, W hite consumers o f the period’s cinematic narratives would have been even more likely to have embraced

- 62. the favored narrative relationships with W hite characters and the negative narrative relationships with cinematically “absent” or caricatured non-Whites, and to have internalized their corresponding emotional templates. The common belief today is that these mechanisms were destroyed with the mid-twentieth century civil rights movement. O ne must recall, however, that the legal remedies, including school desegregation and busing, that ended formal apartheid in the u.s. were not designed to repair the rampant uprootedness caused by centuries o f dedicated racism. Taking seriously Weil’s observation that uprootedness is a psycho-social disorder, it is difficult to imagine how it could have been healed or transformed in the absence o f deliberate therapeutic interventions. Recent scholarly studies o f racism’s impact in several key arenas suggest that the narrative instruments used to generate a racist socialization are re-fashioned and/or re-invented with each generation, and that the untreated uprootedness o f earlier decades continues to self-propagate. In fact, several studies now confirm significant patterns o f racialized thinking in the generation that was born and raised after the narrative instruments o f the pre-Civil Rights era were discredited.

- 63. In March 2002, the Institute of Medicine o f the National Academy o f Sciences released a report titled, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care,” that documented widespread and substantial disparities in the treatment doctors dispensed to Whites and non-W hite patients. The congressionally mandated study noted that these disparities persist “even when insurance status, income, age, and severity o f conditions are comparable.” The report’s authors defined “disparities in healthcare as racial or ethnic differences in the quality o f healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness o f intervention.” They noted that these disparities are associated with greater mortality and are, therefore, “unacceptable.” In “The Apartheid o f Children’s Literature,” published in The New York Times in 2014, writer Christopher Myers cites a 2013 study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center at the University o f Wisconsin showing that only 93 o f the 3,200 children’s books published in 2013 were about

- 64. Black people. A recent study, “W ho believes in me? The effect o f student-teacher demographic match on teacher expectations,” published in the Economics o f Education Review in 2016, reveals that “non-black teachers o f black students have significantly lower expectations than do black teachers,” that “ [t]hese effects are larger for black male students and [non-black] math teachers,” and that Black teachers have equal expectations for their non-Black and Black students. More recently, a study published in the Proceedings o f the National Academy o f Sciences (pnas) in March 2017, “Language from police body camera footage shows racial disparities in officer respect,” confirms that “Police officers speak significantly less respectfully to black than to white community members in everyday traffic stops, even after controlling for officer race, infraction severity, stop location, and stop outcome.” At the time he shot and killed 32-year old Philando Castile in July 2016, M innesota police officer Jeronimo Yanez was a young man in his late 20s. Looking at the dash cam and other footage o f the shooting, it is clear that

- 65. Castile’s killer had no mental script in which a Black man could own a gun and not be a threat. Narrative relationships formed through and with television, cinematic, historical, and other narrative characterizations o f Black men as savages, brutes, and thugs were the likely emotional triggers that preempted his human response to this family. Before, during, and after the killing, Officer Yanez displayed no empathy for Castile, for his girlfriend, nor for the traumatized 4-year old child in the backseat his bullets narrowly missed hitting, a child who will undoubtedly need caring and professional support to become re-rooted. The jury’s endorsement of Yanez’s demeanor suggests that racism’s uprooting is widespread and unabated. For African-Americans, the public slaughter o f men, women, and children by police and by civilians has become an ongoing roadside holocaust. O n the one hand, these killings are consistent with popular understandings o f the ways in which non-Whites are endangered by racism. Read more carefully, however, these developments are also indicative o f a larger pattern of detachment, defective moral reasoning, and misreading responsible for an

- 66. alarming decline in the nations democratic institutions, provisions, and commitments, and an increase in policies that have endangered the poor and middle classes across all racial groups. As discussed above, these new jeopardies are the end-results o f a process set in motion in the seventeenth-century colonies. In their quest to halt, if not reverse, this decline, several commentators have developed lucid descriptions of the threatening behaviors but have failed to examine their psychological foundations in the ideology of race. A useful example is the book What’s the Matter with Kansas? (2004), in which writer Thomas Frank unmasks the voting behaviors o f working and middle class W hite men in endorsing policies and candidates inimical to their own economic interests. Frank blames these developments on what he calls “the Great Backlash, a style of conservatism that first came snarling onto the national stage in response to the partying and protests o f the late sixties”(5) - As he notes, “W hile earlier forms o f conservatism emphasized fiscal sobriety, the backlash mobilizes voters with explosive social issues — summoning public outrage over everything from busing to un-Christian art — which it then marries to pro-business economic policies”^ ).

- 67. Although he faults the Democratic Party for becoming “the other pro-business party,” the group that comes in for a scathing indictm ent in Frank’s analysis is the vast and diverse m ultitude o f working-class voters: sturdy blue-collar patriots reciting the Pledge while they strangle their own life chances;... small farmers proudly voting themselves off the lan d ;... devoted family men carefully seeing to it that their children will never be able to afford college or proper health care;... working-class guys in midwestern cities cheering as they deliver up a landslide for a candidate whose policies will end their way o f life, will transform their region into a ‘rust belt,’ will strike people like them blows from which they will never recover. (10) The working-class political behavior Frank describes can be more fully understood as the calculated effect of focusing illusions. As defined by cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman, a focusing illusion is any single issue that is given an exaggerated importance in decision-making, because o f a false calculation o f its impact on expected

- 68. outcome. Historically, race has been a central focusing illusion for many W hite working-class voters in the u.s. who mistakenly believed that their economic interests and future quality o f life would be secured by supporting candidates who endorsed racist positions. The Trump campaign was perhaps the most successful among recent deployments o f race as a focus illusion. W hite working-class voters thrilled to Trump’s promises to exclude Mexicans, ban Muslims, and dismantle the policies (and legacy) o f the first Black president, (mistakenly) convinced that their lives would be improved by these actions, and, like their seventeenth-century predecessors, that their economic interests would be prioritized and secured by a W hite rich president. The widespread vulnerability to focusing illusions is a direct consequence o f emotional detachment from those “other” people who are (mistakenly) expected to bear the full brunt of particular policy decisions, a detachment ffequendy accompanied and exacerbated by deficits in social literacy and historical thinking. A recent example can be observed in the farmers from California and other Western states who cheered on the Trump

- 69. anti-Mexican, anti-immigrant agenda with no empathy for the psychological distress o f the Mexican workers they had employed for years and whom they knew. Belatedly recognizing that their own economic well-being is dependent on these “disposable” people, these W hite farmers are now anxious to have the administration reverse course. In Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts (2001), education psychologist and cognitive scientist, Samuel W ineburg differentiates between historical knowledge and historical thinking. As he sees it, “to engage in historical thinking [is to be] called on to see hum an motive in the texts we read; called on to mine truth from the quicksand o f innuendo, half-truth, and falsehood that seeks to engulf us each day; called on to brave the fact that certainty, at least in understanding the social world, remains elusive and beyond our grasp” (83). For Wineburg, the ability to engage in historical thinking is an essential component o f “social literacy,” “a literacy n ot o f names and dates but o f discernment, judgment, and caution” (ix). 15 7 B

- 70. LA C K R EN A IS SA N C E N O IR E CODA In a 2012 lecture that now seems prescient, retired Supreme Court justice David Souter expressed his concern that u.s. democracy would be endangered not by foreign agents or military force but by a decline in the populations social literacy. Prefacing his commentary with the observation that “Democracy cannot survive too much ignorance,”

- 71. Justice Souter explained, I don’t worry about our losing republican government in the United States because I’m afraid o f a foreign invasion [...] or a coup by the military as has happened in other places [...] W hat I worry about is that when problems are not addressed people will n ot know who is responsible. [...] If something is not done to improve the level o f civic knowledge, that’s what I worry about.11 Although Justice Souter mentions dangers arising from a lack o f “civic” knowledge, the substance o f his analysis is about dangers stemming from a populace whose ability to engage in historical thinking has been severely diminished. The paradox here is that while racism has largely contributed to the loss o f these essential competencies, a society conditioned to recognize only racialized dangers may not be capable o f fully appreciating or adequately responding to ongoing threats to its democratic institutions when those threats are in White-face. Throughout the nation’s history, race has been the most frequently deployed,

- 72. the most effective mechanism for undermining the interpretive competence and interpretive agency o f people with W hite racial privilege. It does so, first, by its positioning of particular groups on the lower tiers on the hierarchy o f hum an worth and concurrently defining them as disposable. The resulting emotional detachment toward these groups infects and impairs emotional attachment toward other non-racialized groups, eroding the capacity for effective moral reasoning and healthy decision-making. Second, by generating narratives that assign blame to these constituencies for failures in economic and social policy. Third, by orchestrating narrative relationships that function as disabling emotional guides and emotional triggers, inhibiting narrative knowledge and social literacy. And finally, by prescribing indifference regarding threats to those defined as disposable and simultaneously obscuring the connection between such threats and jeopardy to those defined as valuable. Now, at the start o f the Trump presidency, it is becoming all too apparent that u.s. democracy is imperiled by the very intellectual habits that sustain the racial privileges McIntosh and other W hites carry in their “invisible knapsacks.” Despite this, I hope for a future secured

- 73. by the possibilities o f re-rooting through racial self-evaluation, self-diagnosis, and self-correction: a future in which a parent might say to a friend, “I’m worried about my teenage son. He’s showing signs o f racism spectrum disorder.” Or, a volunteer might say o f herself, “I’m beginning to realize I’m on the racism spectrum and that the volunteer work I do really stems from the fact that I don’t see my clients as having the same capacities that I do.” A future in which a co-worker might say, “My parents were on the racism spectrum and worked really hard to provide my brother and me with learning opportunities to make sure that we wouldn’t be.” A future in which a colleague might say, “My students and I are developing a model to counter r.s.d through an elementary school reading curriculum.” O ne in which a political scientist will decide to measure the ways in which r.s.d. — not just the Russians — affected the 2016 presidential elections, and in which doctors and law enforcement officers will be screened for r.s.d using fMRI technology and offered appropriate therapies. A future in which voters who lack personal knowledge of the many strangers on the “trolley tracks” o f domestic and foreign policy debates will seek new narrative knowledge

- 74. and be guided by it in effective moral reasoning and moral responses. O ne in which young people will not need to remind uprooted compatriots that “Black lives matter!” If not this future, then it will be, as writer James Baldwin forewarned, the fire next time. ■ WORKS CITED Baldwin, James. 1962. The Fire Next Time. New York: Vintage Books. Charon, Rita. 2006. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories o f Illness. New York: Oxford University Press. Clark, Kenneth B. and Mamie P. Clark. 1947. "Racial Identification and Preference in Negro Children." E.L. Hartley, ed. Readings in Social Psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart,Winston. Print. Clore, Gerald L., and Janet Palmer. 2009. “Affective guidance of intelligent agents: How emotion controls cognition.” Cognitive Systems Research 10,21-30. Print. Damasio, Antonio, R. 1994. Descartes’Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Print. Frank, Thomas. 2004. What’s the matter with Kansas: how conservatives stole the heart o f America. Gershenson, Seth, Stephen B. Holt, and Nicholas W.

- 75. Papageorge. 2016. "Who believes in me? The effect of student-teacher demographic match on teacher expectations." Economics o f Education Review 52. 209-224. Print. Greene, Joshua D., R. Brian Sommerville, Leigh E. Nystrom, John M. Parley, and Jonathan D. Cohen. 2001. "An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment.”Science Vol. 293, September. 2105-2108. Print. ENDNOTES 1 The Clark study showed th a t contrary to psychological predictions th a t children would prefer dolls that most closely resembled themselves i.e. would display prefer- ence based on similarity bias, Black children rejected as "ugly” the Black dolls with which they identified, and preferred the White dolls instead. 2 Although the followers of Islam include people from all races and nations, the term "Muslim” in the White/Western imagination is as much a signifier of (non-White) racial difference as of religious distinction. 3 McIntosh’s first listing of over 50 privileges appeared in a 1988 essay titled “White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences through Work in Women’s Studies.” A year later, she published an abridged version of the essay, titled "Unpacking th e Invisible Knapsack,” with a shorter list of only 26 privileges. 4 This privilege is listed in the 1988 but not the 1989 version.

- 76. 5 Wahneema Lubiano, “Introduction,” p.vii. Harrison, Mary-Catherine. 2011. “How Narrative Relationships Overcome Empathic Bias: Elizabeth Gaskell’s Empathy across Social Difference.” Poetics Today 32:2 (Summer). 255-288. Print. Institute of Medicine. 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky, eds. 2000. Choices, Values, and Frames. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Print. Lubiano, Wahneema, ed. 1997. “Introduction.” The House That Race Built. New York: Vintage Books. Print. McIntosh, Peggy. 1989. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” Peace and Freedom July/August: io-i2. Print. Morrison, Toni. 1970. The Bluest Eye. New York: Knopf. Print. Myers, Christopher. 2014. “The Apartheid of Children’s Literature.” The New York Times Sunday Review March 15. Print. Olson, Joel. 2001. “The Democratic Problem of th e White Citizen.” Constellations Vol. 8, No. 2. Print. Powell, John A. 2007. "Structural Racism: Building upon the Insights of John Calmore." North Carolina Law Review 86:791- 816. Print.

- 77. 6 As Gerald L. Clore and Janet Palmer note, "it turns out that affect and emotion play critical roles in good judgm ent and in the adaptive regulation of thought." 7 According to Greene and his colleagues, “Typical examples of non-moral dilemmas posed questions about whether to travel by bus or by train given certain tim e constraints and about which of two coupons to use at a store" (2106). 8 To Charon's listing of “life settings” in which narrative knowledge is essential, I would add the many other social and professional arenas — neighborhoods, k-through-12 classrooms, airports, restaurants, playgrounds, police precincts, newsrooms, legislative chambers, and corporate boardrooms — in which citizens interact in our democracy. 9 It is im portant to note th a t a lack of empathy on th e part of the ruling elite does not typically involve th e familiar displays of petty criminals. In fact, these displays are usually not defined as criminal. Nevertheless, the characteristics associated with a lack of empathy are obviously at work in the economic policies and behaviors of the ruling elite who are frequently detached from working-class employ- ees, tenants, patients, students, clients, and other subordinates. Souter, David. 2012. “Constitutionally Speaking with Justice David Souter and PBS senior correspondent Margaret Warner.” September 14. Capitol Center for the Arts, Concord, New Hampshire. Audio. Tatum, Beverly. 1997. Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? And Other Conversations