Type of discipline guidanceHow it worksAdvicecautionsReinf.docx

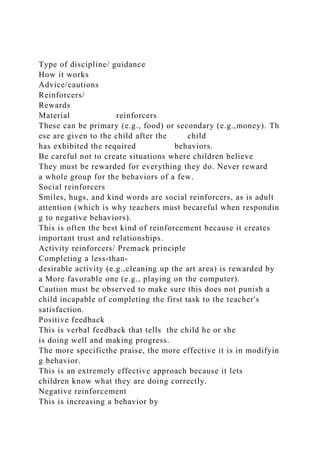

- 1. Type of discipline/ guidance How it works Advice/cautions Reinforcers/ Rewards Material reinforcers These can be primary (e.g., food) or secondary (e.g.,money). Th ese are given to the child after the child has exhibited the required behaviors. Be careful not to create situations where children believe They must be rewarded for everything they do. Never reward a whole group for the behaviors of a few. Social reinforcers Smiles, hugs, and kind words are social reinforcers, as is adult attention (which is why teachers must becareful when respondin g to negative behaviors). This is often the best kind of reinforcement because it creates important trust and relationships. Activity reinforcers/ Premack principle Completing a less-than- desirable activity (e.g.,cleaning up the art area) is rewarded by a More favorable one (e.g., playing on the computer). Caution must be observed to make sure this does not punish a child incapable of completing the first task to the teacher's satisfaction. Positive feedback This is verbal feedback that tells the child he or she is doing well and making progress. The more specificthe praise, the more effective it is in modifyin g behavior. This is an extremely effective approach because it lets children know what they are doing correctly. Negative reinforcement This is increasing a behavior by

- 2. removing a negativestimulus. For example, children will compl ete work more quickly so they can go to the playground sooner. Rather than using negative reinforcement, teachers should determine whether the behavior children are trying to avoid could be made more meaningful and interesting. Token economy Children's appropriate behavior is rewarded immediately with tokens, which are exchanged for material reinforcers or privileges. Tokens must be exchanged for things students really want; a choice should also be provided. Many believe tokens do not work with children under age 5. Intrinsic reinforcement Intrinsic reinforcement comes from within the child: feelings of success or happiness, or a sense of competence or pride. The ultimate goal of discipline and guidance is that they are internalized. Some people believe using extrinsic reinforcers reduces the power of intrinsic reinforcement. Punishments Natural consequences This is the natural result of what a child does or does not do. A child who forgets to put on a jacket will get cold on a winter day. A child who comes late to the meal may miss out on his or her favorite food. This works only when adults are willing to let go, and to let the child live with the consequences of his or her behaviors. A child needs to be able to make the connection between the behavior and the result. Logical consequences If a child spills milk, a logical consequence is to have him or her clean up the mess; a logical consequence for a child drawing on a table is to have him or her scrub the table clean. The focus should be on fixing the problem and not on the

- 3. punishment. The child must be able to see how he or she caused the problem and how the action helps to fix it. Unrelated consequence A child who does not complete a math assignment is prevented from playing on the playground. There is no logical connection between the behavior and the consequence. This approach should be avoided as much as possible, because it does not teach anything and can backfire. Response cost A child's inappropriate behavior is punished by removing a privilege he or she has earned. For example, a child may earn money for a task and then have it taken away for disobeying. This approach is most effective when combined with positive reinforcement for appropriate behavior, and when the child does not lose everything he or she has earned. Verbal reprimands This is a verbal response by the adult to the child's inappropriate behavior. The response should not be sarcastic, in anger, or degrading. It should inform the child of how he or she can engage in the appropriate behavior. Verbal reprimands are more effective when they are brief, immediate, and accompanied by eye contact or a firm grip. They should be softly spoken and include a statement acknowledging that the child is capable of exhibiting the appropriate behavior. Time out This is a punishment that removes a child from a pleasurable, engaging, or enjoyable situation. The setting should not be reinforcing and the duration of the punishment should be quite short. Time out should be used sparingly and at the highest end of a behavioral continuum. If it ends up being used frequently, it is not working. Modeling

- 4. Modeling is a very powerful way to teach both appropriate and inappropriate behaviors. It works by the child observing an adult or child who has prestige and competence in a certain behavior or skill. Adults and children whom other children see as behavioral and learning models must be extremely consistent in their behaviors. It is ineffective to say, "Do as I say, not as I do!" ORG 6700, Diversity and Inclusion in the Organization Culture 1 Course Learning Outcomes for Unit II Upon completion of this unit, students should be able to: 3. Compare and contrast dysfunctional and healthy thought- behavior processes as they relate to diversity and inclusion. 3.1 Evaluate stereotypes that impede an organization’s efforts for diversity and inclusion. 3.2 Evaluate discriminatory practices that impede an organization’s efforts for diversity and inclusion. 3.3 Develop strategies for transforming a dysfunctional mental model—based on stereotypes and discriminatory practices—to a healthy mental model.

- 5. Reading Assignment Read the following journal article from the Business Source Complete database in the Waldorf Online Library: Martinez, E. (2010). The air up there. OD Practitioner, 42(2), 14-18. Read the following article from the Opposing Viewpoints database in the Waldorf Online Library (Note: In the Opposing Viewpoints database, type the article title in the “search” bar to obtain the article.): Levin, J., & Nolan, J. (2014). Racism and Anti-Semitism Are Often Culturally Validated. In N. Berlatsky (Ed.), Opposing Viewpoints. Anti-Semitism. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Press. (Reprinted from The Violence of Hate: Confronting Racism, Anti-Semitism, and Other Forms of Bigotry, n.d., Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ) Watch the following video clips from the Films on Demand database in the Waldorf Online Library: Library Project” (10 minutes, 33 seconds)* * If this video clip is not available, instead read the following

- 6. article from the Academic Search Complete database in the Waldorf Online Library: Kinsley, L. (2009). Lismore’s living library: Connecting communities through conversation. APLIS, 22(1), 20-25. Unit Lesson Think of examples of workplace stereotypes and discrimination that you have observed. Left unchecked, an organization’s culture plays a major role in perpetuating those stereotypes and discriminatory behaviors. However, with an intervention designed to replace dysfunctional patterns of stereotyping and discrimination with more productive thought-behavior patterns, the organization’s culture will also play a major role in that change (Friesenborg, 2015; Schein, 2009). Comparing these two scenarios, organization culture can either be part of the problem or part of the solution. The difference is whether there is an intervention led by a leader or a consultant who is well-versed in the use-of-self as an instrument for change (Friesenborg, 2015). UNIT II STUDY GUIDE Cultural Stereotypes and Discrimination

- 7. ORG 6700, Diversity and Inclusion in the Organization Culture 2 UNIT x STUDY GUIDE Title Socio-Cognitive Systems Learning Model The phrase socio-cognitive focuses on the thought-behavior patterns that people have about themselves and others, as social beings. The Socio-Cognitive Systems Learning Model is a diagram that compares two systems of values, behaviors, and outcomes: (a) Model I (i.e., the dysfunctional “default” system that perpetuates stereotyping and discrimination) and (b) Model II (i.e., the alternative, healthy, more productive system that must be learned; Argyris, 2000, 20014, 2006a, 2006b, 2010; Argyris & Schön, 1996; Friesenborg, 2015). Click here to view a document that depicts the Socio-Cognitive Systems Learning Model. It includes two figures. First, look at Figure 2, the simplified version of the Socio-Cognitive Systems Learning Model. The center row, shaded in black, shows the elements that comprise a socio-cognitive process: values, behaviors, and outcomes. Each of these three elements is influenced by culture, which is mutually influenced by the organization and the individual as patterns of meaning flow between them (Argyris, 2000, 20014, 2006a, 2006b, 2010; Argyris & Schön, 1996; Friesenborg, 2015; Schein, 2009). At the top of the diagram, you will see the pattern of values, behaviors, and outcomes of the Model I process. At the bottom of the diagram, you

- 8. will see the pattern of values, behaviors, and outcomes of the Model II process (Friesenborg, 2015). Let us look at these patterns in more detail, using both Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 is the Socio-Cognitive Systems Learning Model, and Figure 2 is a simplified version to use as an introduction for understanding Figure 1. Model I: Accommodating Stereotyping and Discrimination Take a closer look at the Model I process, the cultural default process that is typically in place unless an intervention takes place (Friesenborg, 2015). We will also weave a general example of stereotyping and discrimination throughout the interrelated system of Model I values, behaviors, and outcomes to demonstrate how this system works. Model I Values The Model I values are self-centered. The individual espouses (or pays lip-service) to values that are idealized by the culture, but his or her real, underlying values revolve around his or her own self-centered desires and goals (Argyris, 2000, 20014, 2006a, 2006b, 2010; Argyris & Schön, 1996; Friesenborg, 2015). For example, people may claim to value the cultural ideals of equality and fairness. However, their deep, underlying values reflect their own self-centered desires and goals. Their deep, underlying values also hold stereotypes, such as those about women, people from minority races, people in poverty, people with other religious practices, people who are skinny, people who are overweight, people who are young, people who are old, people perceived as beautiful, people perceived as ugly, or people from a variety of other

- 9. demographic groups. While individuals may pay lip service to equality and fairness, they are mainly concerned with their own self-centered desires and goals, padding their egos and often comparing themselves to those they stereotype. Model I Behaviors The Model I behaviors are self-centered behaviors that revolve around gaining unilateral control by competing for recognition, accruing social capital, and either punishing or threatening people. Model I behaviors also revolve around both blame and evasive behaviors that are designed to defend oneself. These defensive behaviors also protect the contradiction between the real and espoused values from being analyzed. This charade makes certain topics undiscussable (Argyris, 2000, 20014, 2006a, 2006b, 2010; Argyris & Schön, 1996; Friesenborg, 2015). Let us continue the example described above, with people espousing equality and fairness, yet truly valuing their own self-centered desires and goals that are justified by stereotyping other people based on their demographic backgrounds. These Model I values are subconsciously applied through Model I behaviors. Using this example, the stereotypes that are woven into people’s values are expressed through discriminatory behaviors, which may be either subtle or explicit. Using the example from above, a group of people believe themselves to be superior to people from another demographic group, so they seize unilateral control, which they believe to be rightfully theirs. They may blame the other demographic group or avoid extending opportunities to people of that group. Through it all, they subconsciously shroud the contradiction between

- 10. https://online.waldorf.edu/CSU_Content/Waldorf_Content/ZUL U/Business/ORG/ORG6700/W14Aw/UnitV_VII_VIII_Socio- CognitivegModel.pdf ORG 6700, Diversity and Inclusion in the Organization Culture 3 UNIT x STUDY GUIDE Title their discriminatory actions and their espoused values about equality and fairness, making the contradiction undiscussable. Model I Outcomes A Model I system that includes stereotypical values and discriminatory behaviors results in outcomes that are riddled with pain and frustration among those people on the receiving end of the stereotypes and discrimination. This can lead to mistrust. People do not trust others who stereotype and discriminate against them. This destruction of trust typically results in the escalation of problems (Argyris, 2000, 20014, 2006a, 2006b, 2010; Argyris & Schön, 1996; Friesenborg, 2015). Single-Loop Learning A socio-cognitive process is a cycle, a living system, and not just a snapshot in time. The people involved will

- 11. respond to the Model I outcomes by reverting to Model I behaviors, which can include seeking more unilateral control, blaming, and using fancy footwork. Fancy footwork consists of actions that deflect blame from oneself and often redirect blame, undermining the other party involved in the situation. Look at Figure 1, the Socio- Cognitive Systems Learning Model. Single-loop learning creates a vicious cycle between Model I behaviors and Model I outcomes, producing resistance to productive learning and change. Assumptions and values are not tested through Model I, although the ugliness of the vicious cycle fuels the self-centered focus of the values of each person involved (Argyris, 2000, 20014, 2006a, 2006b, 2010; Argyris & Schön, 1996; Friesenborg, 2015). So, how can we change if this vicious cycle fuels itself? Before we discuss interventions, we should contrast Model I to the Model II socio-cognitive process. Model II: Seeking to Understand People of Diverse Backgrounds The Model II socio-cognitive process is an alternative to the Model I default. Model II Values Model II values are based on understanding yourself and other people. This is accomplished by acknowledging and testing assumptions or stereotypes, both about yourself and about other people. Even the most well-meaning of people are likely to have some inaccurate assumptions or stereotypes because it is human nature to judge people and situations. Model II values seek to uncover these assumptions and

- 12. stereotypes, so they may be dealt with as the person seeks to understand herself or himself and other people. Model II Behaviors Model II behaviors are centered on dialogue as the primary means of better understanding oneself and other people. People from diverse backgrounds are included and welcomed to participate, and the ground rules include treating each other with respect and providing the freedom to disagree and the freedom to discuss the undiscussable In this way, people discuss any elephants in the room. This is not a debate to prove oneself right, but instead it is a dialogue that focuses on asking questions, listening, and observing. First Loop of Double-Loop Learning In contrast to Model I, Model II has two feedback loops. Also different from Model I, the Model II feedback loops both target one’s values: “acknowledging and testing assumptions to understanding (one’s) true self and other people” (Friesenborg, 2015, p. 9). For the first loop of double-loop learning, you use the information and observations gleaned from the dialogue (i.e., the Model II behaviors) to better understand yourself and others by uncovering and acknowledging stereotypes that you have held, as well as uncovering any potential discrimination that you have practiced. ORG 6700, Diversity and Inclusion in the Organization Culture

- 13. 4 UNIT x STUDY GUIDE Title Model II Outcomes Through Model II, problems are typically resolved, and the people involved receive a sense of peace. Having provided a psychologically safe environment for dialogue, they trust each other. Ultimately, Model II typically results in productive learning and change. Second Loop of Double-Loop Learning With the second loop of double-loop learning, the individuals reflect on the outcomes to further inform their values. The Model II outcomes produce a sense of wholeness, which aligns with Model II values. Unlike the values and outcomes of Model I, Model II’s values and outcomes are congruent or complementary. If wholeness-oriented outcomes were not achieved and the values and outcomes do not yet align, more dialogue is needed. Intervention: Transformative Learning from Model I to Model II Model II is clearly the more productive thought-behavior pattern. How do we lead people from Model I to Model II? One way to lead this change is through intervention. An intervention is defined as a change agent’s deliberate action that is designed to replace old thought- behavior patterns with new ways of thinking and behaving

- 14. (Cummings & Worley, 2009). An intervention may take a variety of forms. In this unit, we will discuss both informal and formal interventions, as well as small- scale and large-scale approaches. Each of these forms of intervention is typically driven by ethics and by an ethically-driven interest in generating change to help people. Below are some examples of interventions. Individual-Level Intervention By learning about the culture of learning organizations and how culture impacts diversity and inclusion, you are developing an awareness of Model I and Model II patterns. As you interact with people in the organization and you recognize Model II behaviors and outcomes, you have the opportunity to initiate a Model II feedback loop aimed at Model II values. The feedback loop is designed to seek the perspectives of other people in order to better understand yourself and other people. In other words, you have the opportunity to initiate dialogue and other Model II behaviors with others with the goal of better understanding yourself and better understanding other people. This also creates an environment for the other person to do the same. The feedback loop makes the connection between actions and underlying values. When you recognize Model I behaviors and outcomes among other people, you have the opportunity to initiate Model II dialogue in order to generate a Model II feedback loop, helping other people to better understand themselves and other people from diverse backgrounds. As you are speaking one-on-one with an individual who is making assumptions or stereotypes about a person based on that person’s group affiliation, you may use self-as-instrument to initiate dialogue with that

- 15. person. For example, if an individual in your organization tells a joke that fuels stereotypes or demeans people of a particular demographic group, you might dialogue with that person to help him or her see the perspective of people from that demographic group. As another example, a leader might make an off-hand comment that a particular job candidate is less desirable because he or she is older or nearing retirement. However, maybe it is not something that someone said, but it might be an observation that someone is being excluded based on his or her membership within a particular demographic group. For example, the leadership may decide to launch a plumb project, but the employees considered for that project may be limited to males. Based on this observation, you would have the opportunity to discuss your observation with the leaders and ask if there are women (or members of other under-represented groups) who might also qualify to participate in the project. Prompting a Model II feedback loop may be considered a small- scale intervention as you dialogue with people to help them develop awareness of their Model I patterns and to use dialogue and other Model II behaviors. The goal is to help people recognize the assumptions they have about people and to probe those assumptions—by seeking to understand the perspectives of other people from diverse backgrounds—in order to identify whether those assumptions are baseless stereotypes or whether the assumptions are valid.

- 16. ORG 6700, Diversity and Inclusion in the Organization Culture 5 UNIT x STUDY GUIDE Title One note of caution: Be careful that you create a psychologically safe environment in order to avoid the inclination for others to respond defensively. Also, be careful that you do not fall into Model I traps as you seek to help others recognize their stereotypes. Your goal is not to prove them wrong or prove yourself right, as those are actions are indicative of Model I behaviors designed to achieve unilateral control or blame. Instead, think of yourself as a coach whose role is to ask questions in order to help people consider new angles. In the process, you may learn more about yourself as well, and you may even realize assumptions and stereotypes that you have held. Intervention at the Team-Level Organizational change may occur through either a formal or an informal intervention, led by one or more people within the team or by an external consultant. In both cases, the leader or consultant uses self-as- instrument to initiate change by helping people to dialogue in order to better understand themselves and other people. Like the individual-level intervention described above, interventions at the team level also use a Model II feedback loop to help people learn from the diverse

- 17. perspectives of other people. The goal is to create a culture that uses Model II. Intervention at the Organization-Level Depending on the scale of the intervention, particularly with a large team or an entire organization, you may wish to enlist the help of an external consultant who is well- versed in transformative change through the development of a Model II culture. The tools presented in this class may help initiate an intervention at the individual level and perhaps among small teams. Conclusion Model II includes excellent strategies for dispelling stereotypes and abolishing discriminatory practices. Think about how Model I and Model II apply to the examples in the Required Readings. Also, seek to recognize examples of Model I and Model II in your own experience and think about how you might lead those relationships from Model I to Model II, achieving productive learning and change. References Argyris, C. (2000). Flawed advice and the management trap. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Argyris, C. (2004). Reasons and rationalizations: The limits to organizational knowledge. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- 18. Argyris, C. (2006a). Effective intervention activity. In J. V. Gallos (Ed.), Organization development (pp. 158-184). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Argyris, C. (2006b). Teaching smart people to learn. In J. V. Gallos (Ed.), Organization development (pp. 267-285). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Argyris, C. (2010). Organizational traps: Leadership, culture, organizational design. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Argyris, C., & Schön, D. A. (1996). Organizational learning II: Theory, method, and practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Cummings, T. G., & Worley, C. G. (2009). Organization development & change. Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning. Friesenborg, L. (2015). The culture of learning organizations: Understanding Argyris’ theory through a Socio-Cognitive Systems Learning Model. Manuscript submitted for publication. Schein, E. H. (2009). The corporate culture survival guide (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- 19. 7.3 Approaches to the Guidance and Discipline of Young Children It is important to remember that the goal of discipline and guidance is to help children internalize important rules and societal expectations. If the discipline or guidance approach a caregiver uses is consistent with Erikson's stages of psychosocial development, success will be higher, and the caregiver will be less frustrated. Further, when all parties involved in disciplining a child are consistent, the results will be more effective. These various approaches are summarized in Table 7.1. An important category of learning is behaviorism, which is an observable change of behavior caused by the environment (Ormrod, 2008). Behaviorism can be roughly divided into two overall categories: rewards (known as positive and negative reinforcement) and punishments. (The exception to this rule is the social cognitive approach [modeling], which is both behavioral and cognitive.) Rewards/Reinforcements A reward, or positive reinforcement, is the consequence of a child's behaviors that increases the probability of it recurring (Marzano, 2003). Rewards can be a smile or a positive personal message, such as "I love how you put the books back on the shelf." Rewards can also be in the form of external privileges, such as the use of the computer after the child has finished an assignment. Rewards include things like money, toys, candy, dessert (after eating a main meal), tokens, and stickers. Reinforcing agents, or reinforcers, can be primary reinforcers or secondary reinforcers. Primary reinforcers satisfy a built-in need or desire, such as food, water, air, or warmth, and are essential to our well-being. Other primary reinforcers, such as candy, are not essential, but physical affection, a smile, and cuddling would seem to be (Ormrod, 2008). There are individual differences regarding the effectiveness of these rewards. For example, for someone who does not like chocolate,

- 20. chocolate is not a reinforcer. Secondary reinforcers are previously neutral stimuli that, through repeated association with another reinforcer, have become a reinforcer. A neutral stimulus is a stimulus that a person does not respond to in any noticeable way. For example, initially ringing a small bell in the classroom causes no response from the children; however, after the bell is continually followed by a snack, the bell will produce a marked response. Other examples of secondary reinforcers are praise, tokens, money, good grades, and a feeling of success. Extrinsic Reinforcement Positive reinforcers are rewards that increase a person's behavior, such as a smile from the teacher after a child has helped another child solve a problem, or the feeling of satisfaction when one has completed a difficult task. They are arranged into two different categories: extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic reinforcements are rewards provided by the outside environment. Material reinforcers. These are actual objects, such as food, toys, or candy. While this approach is extremely effective in changing behavior, it can be counterproductive, as it focuses the child's learning on achieving the reward, rather than on the complexities and strategies required to learn. Social reinforcers. Social reinforcers are gestures or signs (a smile, praise, or attention) that one person gives to another. Teachers' attention, approval, and praise are powerful and effective reinforcers (McKerchar & Thompson, 2004). Activity reinforcers. This is the opportunity to engage in a favorite activity after completing a less favorable one. It is called the Premack principle. The more desirable activity is contingent on the completion of the less desirable one (Premack, 1959). Positive feedback. Positive feedback works when it

- 21. communicates to the child that he or she is doing well or making progress, and it is particularly effective when it gives students guidance about what they have learned and how to improve their behavior. Students think about this information in an effort to modify their behavior (Ormrod, 2008). Token economies. A token economy is a program in which individuals who have behaved appropriately receive a token—an item that can later be traded for objects or privileges of the child's choice. Most children under age 5 cannot benefit from a token economy due to their developmental stage and lack of experience. Intrinsic Reinforcement Intrinsic reinforcements are the internal good feelings that come from within the child. Feelings of success, pride, and relief at completing a task or assignment are all examples of intrinsic reinforcement. For many young children, the motivation for achieving a variety of new skills and tasks, from learning to walk and talk to toilet training and holding a spoon, come from a deep sense of accomplishment and personal satisfaction. Rather than generally praising children for what they have attempted or achieved, a parent or teacher can praise the effort: "I like how you kept trying until you were able to tie your shoe" and "I see how carefully you decided which tomatoes were ripe enough to pick, and which were the ones that needed to stay on the plant." Negative Reinforcement Negative reinforcement increases a response through the removal of a stimulus—usually an unpleasant one. Thus, negative reinforcement occurs when something negative is taken away to improve a behavior. Telling children they can leave the classroom to go to the playground once they have completed their math activity is negative reinforcement. Other examples include when a parent picks up a crying baby (negative stimuli)

- 22. and the baby stops crying, as well as the annoying buzzer in your car that keeps going until you put on the seatbelt (you put on the seatbelt [the desired behavior] to get rid of the annoying noise [the negative stimuli]). Punishment Punishment is a behavioral approach that attempts to reduce a child's inappropriate behavior (Ormrod, 2008). There are two kinds of punishment: (1) the presentation of a negative stimulus, for example, scolding a child who has misbehaved or assigning a failing grade after a child did not complete an academic task; and (2) removal of a stimulus, usually a pleasant one. This could be, for example, taking away an allowance or the loss of special privileges. Both kinds of punishment reduce the target behavior. Forms of punishment used in early care, education programs, and homes include natural consequences, logical consequences, unrelated consequences, response cost, verbal reprimands, and time out. Punishment does not directly help the child gain emotional regulation or internalize accepted behaviors, but it does help children (if used consistently) know which behaviors are acceptable and which are not acceptable (Bodrova & Leong, 2007). Problems with the Use of Punishment to Modify Children's Behavior Though punishment is a very popular approach used by adults with young children (both parents and early care and education staff) and can be very effective (Hall et al., 1976), it tends to be overused and is fraught with problems. For example, a punished behavior is not eliminated. It often reappears when the person doing the punishing leaves, thus requiring constant adult supervision at home and in the program. Further, punishment does not address the cause of the behavior. Often, there are clear and salient reasons why a young child is behaving a specific way in a specific situation, and it is important that these causes be addressed.

- 23. In some situations, punishment can actually lead to an increase in the behavior that is being punished. This can occur in two ways. If punishment is the only attention the child gets from the adult, the child will continue to engage in the behavior for attention. Punishment can also increase the behavior in a setting where there is no one to control it; for example, punishing certain bad language in the classroom can increase the use of the same language on the playground. Further, young children are often unaware of the specific behavior being punished, and then they believe they are being punished for being "a bad child." This develops low self-esteem, particularly in young children who take an all or nothing view of personal criticism (e.g., "I am all good" or "I am all bad"). Punishment can also lead to children avoiding certain places and activities. For example, a child who always does poorly at an assignment, such as math, and is punished for it, may not only learn to avoid math, but may learn to dislike school because he or she learns to associate all of school with math (Smith & Smoll, 1997). When punishment is used on children, they are not always being shown how to engage in the appropriate behavior. The punishment only tells them what not to do and what they are doing poorly; it does not teach anything about what they should be doing instead. Often, children do not know how to engage in the socially acceptable alternative to aggression (for example, how to resolve a conflict without being aggressive). A child who grabs a toy from another child may not understand that there is another way to get what he or she wants; a child who bites another child may not have the language to communicate his or her anger and frustration. Punishment can also lead to aggression and later to bullying (Landrum & Kauffman, 2006), because it models aggressive behavior and the use of power by adults to achieve their goals (see Helping Children Develop: Do as I Do: The Power of Example).

- 24. Finally, severe punishment can lead to emotional and physical harm. Punishment can potentially lead to child abuse; many adults with low self-esteem can trace this back to receiving constant and harsh negative putdowns and punishment as children (Smith & Fong, 2004), and parents who were abused as children are more likely to become abusers themselves (Milner et al., 2010). Natural and Logical Consequences Natural and logical consequences are forms of punishment that make much more sense to children and teach them that certain behaviors have consequences, some of which are unpleasant. Natural Consequences Natural consequences are the result of a child's behavior without any direct involvement by an adult. They teach children the causes and effects of certain behaviors. For example, if a child fails to put on a jacket, the natural consequence is that he or she might get cold; a child who comes late to lunch may get cold food or fewer food choices. Natural consequences do not work when a child is too young to make the connection between cause and effect. They also do not work when the adults involved are overly protective and do not allow children to "suffer the consequences" of their actions or inactions. Logical Consequences Logical consequences occur when a child must rectify a situation or repair damage caused by his or her behavior. When a child spills milk on the floor, the logical consequence is for the child to help clean up the milk; if a child draws on a table top, the logical consequence is for the child to scrub the table top clean. Logical consequences only work when the following occur: Children are able to make the connection between their

- 25. behavior, the consequences of that behavior, and what they are then asked to do. This connection develops during the preschool years, through experience and brain development. The consequence is logical. Preventing a child from going outside to play because he misbehaved in the classroom is not a logical consequence. The consequence occurs immediately after the infraction takes place. A logical consequence might be to remove a child from an activity or group, which is called time away. For example, a child who continually knocks down other children's constructions in the block area may be asked to leave for a while; but again, this consequence must be logical and timely. Because logical consequences require a child to "fix" the problem, they are rarely something the child would choose to do and thus are not often viewed by the child as a reward. However, the child learns that if he or she wants to participate in an activity, or do what the other children are doing, then he or she needs to engage in the appropriate behaviors. While time away is a form of time out (discussed later in the chapter), its focus is on making it clear to the child that removal from the activity is directly related to the child's behavior. Unrelated Consequences Unrelated consequences are the punishment of a child's inappropriate behavior with something that is totally unrelated to the behavior—as in the example of keeping a child from outdoor play after he or she has misbehaved inside the classroom. Because the consequence is not logically related to the behavior, this approach is usually ineffective (Ormrod, 2008). It can also misfire; for example, the child who is kept indoors because he or she misbehaved may need to go outside to burn off energy and take a rest from academic activities; preventing this will cause further classroom disruption. Response Cost

- 26. Response cost involves taking away something the child previously earned. Thus, a child might have earned time at the computer by cleaning up the art area but now loses this privilege due to fighting with another child. The response cost approach is most effective when used with positive reinforcement for an appropriate behavior and when the child does not lose everything he or she has earned by only a small infraction (Phillips et al., 1971). When children lose everything they have earned, they will soon not bother to earn anything. Verbal Reprimands Verbal reprimands are more effective when they are immediate, brief, and accompanied by eye contact or a firm grip (Pfiffner & O'Leary, 1993). (See Chapter 6 for a discussion on this in relation to eye contact.) A verbal reprimand may also be more effective when spoken quietly and close to the child, thus not bringing attention to the child, which would cause guilt and shame. Verbal reprimands should also provide an encouraging statement indicating the caregiver knows the child can engage in the appropriate behavior (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002). Time Out Time out is punishment because the child is removed from a pleasurable and enjoyable stimulus due to his or her inappropriate behavior (Skiba & Raison, 1990). Time out differs from time away in that time out is a general punishment for any kind of behavioral problems, while time away is removal of the child when the child's behavior directly results in the disruption of an activity. Further, in time away, the focus is on the child understanding the relationship between his or her behavior and the resultant disruption, and not on putting the child in a stimulus-free environment (removal is the punishment). In time out, the child is usually removed to another room or a corner of the classroom that is screened off. The time out environment should not be reinforcing, such as the school corridor or principal's office—or frightening, such as a dark closet (Walker

- 27. & Shea, 1995). Time out is usually quite short—for example, one minute for each year of a child's age. A key for using time out is that a child's release from the environment is contingent on the child's demonstrating the appropriate behavior. Time out has been shown to be effective in reducing a variety of disruptive and inappropriate behaviors (Pfiffner & Barkley, 1998; Rortvedt & Mittenberger, 1994) and does not interfere with the ongoing classroom activities and events. Time out also does not give undue attention (a reward) to the child. Modeling Modeling is both a behavioral and cognitive process of social learning by which a person observes the actions of others and then copies them. The academic term for modeling is social cognitive theory. Infants imitate facial expressions of others within a day or two after birth. By 6–9 months of age, they learn new ways to manipulate objects by watching a model demonstrate those behaviors, and by 18 months of age, they remember how to imitate an action they observed a month before (Collie & Hayne, 1999). Albert Bandura is the theorist most associated with our understanding of modeling. According to Bandura, modeling can teach new behaviors, increase the frequency of previously forbidden behaviors, and increase the frequency of similar (but not exactly the same) behaviors (1977, 1986). From a discipline perspective, modeling can teach and increase desired behaviors, such as putting blocks back on a shelf like a teacher or classmate does. Negative behaviors can also increase through modeling (e.g., teasing Johnny because others are doing so) (see Helping Children Develop: Do as I Do: The Power of Example). Modeling works by the learner (child) observing the behavior of the model (adult, peer). After the behavior of the model is reinforced, the learner repeats the behavior. The reinforcement of the model's behavior is called vicarious reinforcement and is the behavioral part of the theory. The ability of the child to

- 28. imitate the model's behavior (even some time later) and the motivation to do so make up the cognitive part of modeling. As mentioned, children can learn both appropriate and inappropriate behaviors through modeling. A great amount of research has been conducted on learning aggression from real models and from film, television, and video game models. These studies show the powerful effect of models on teaching children aggressive behaviors (Bandura, 1986). However, modeling (both real and symbolic) can also effectively teach prosocial behaviors—those aimed at helping others (Bandura & McDonald, 1963). HELPING CHILDREN DEVELOP: Do as I Do: The Power of Example It works better than rewards and punishments to change a child's behavior. It works better than direct instruction to teach academic skills and concepts. It explains why children imitate the behavior of people and characters their parents and teachers might find unacceptable. It is one of the most effective ways for parents to help their children develop important literacy skills. What is This Miraculous Thing? Social cognitive theory. Commonly called modeling, social cognitive theory is a very powerful, yet often misunderstood, method for teaching young children. Children will imitate the behavior of a role model, which can be a live person or a symbolic model such as a character from a TV program, movie, video game, or book. Unfortunately, the behaviors they copy may be appropriate or inappropriate—it

- 29. works equally well for both! But social cognitive theory is more complex than simply copying a role model. The theory is powerful because it combines cognition (thinking), behaviorism (rewards and punishment), and motivation. For modeling to work, the following conditions must be met: The model must be competent in the area or skill being modeled. While a professional athlete would be a good model for encouraging athletics in children, he or she may not be an effective model for teaching children to read. The model must have respect and stature in the eyes of the learner. The model must model behavior in which the child is already interested. For example, someone who can speak Portuguese is likely to be a role model for someone who is about to go to Brazil and wants to learn Portuguese. But this same person is not likely to be a role model for someone who has no interest in learning Portuguese. The role model's behavior must be reinforced in some way. Many children look up to professional athletes and rap stars, for example, because these stars' actions are seen by the children to be rewarded with money and the things money can buy, such as fancy cars, big houses, and expensive jewelry and clothing. Teachers, parents, and even children can become role models for teaching good or bad behavior. If Johnny, a popular boy in the classroom, picks on another child and other children laugh while the teacher ignores his behavior, other children are likely to engage in this kind of bullying behavior. If, on the other hand, when Johnny teases another child the teacher sternly cautions him and removes him from the action for a short while, chances are the other children in the classroom will not mimic Johnny's behavior, because it is not being rewarded. Uses of Social Cognitive Theory When a teacher wants a young child to clean up after the child has played with blocks, the teacher can tell the child to replace

- 30. the blocks on the shelves and threaten him or her with some sort of punishment if the task is not done, or the teacher can get down on the floor with the child and show him or her how to put the blocks on the shelf, making it a pleasant experience. Then, when the child has finished, the teacher can praise the child for helping. If a parent wants to help a child learn to read, the best thing the parent can do is model reading to the child. Modeling can be done by reading a newspaper or book, reading the directions aloud when a child wants to make something, and reading books to the child on a regular basis. This will help the child realize that reading is a pleasant and rewarding experience. Finally, if parents and teachers want to know why a child is using bad language or engaging in poor behavior on the playground or in the classroom, they usually only have to look as far as the role models in the child's life, which sometimes means reflecting on their own behavior and making positive changes. Wardle, F. (2003). Do as I do: Power of example. Children and Families, 17(4), pp. 62–63. National Head Start Association. Table 7.1: Approaches to guidance and discipline with young children Type of discipline/ guidance How it works Advice/cautions Reinforcers/ Rewards

- 31. Material reinforcers These can be primary (e.g., food) or secondary (e.g.,money). Th ese are given to the child after the child has exhibited the required behaviors. Be careful not to create situations where children believe They must be rewarded for everything they do. Never reward a whole group for the behaviors of a few. Social reinforcers Smiles, hugs, and kind words are social reinforcers, as is adult attention (which is why teachers must becareful when respondin g to negative behaviors). This is often the best kind of reinforcement because itcreates important trust and relationships. Activity reinforcers/ Premack principle Completing a less-than- desirable activity (e.g.,cleaning up the art area) is rewarded by a More favorable one (e.g., playing on the computer). Caution must be observed to make sure this does not punisha child incapable of completing the first task to the teacher's satisfaction. Positive feedback This is verbal feedback that tells the child he or she is doing well and making progress. The more specificthe praise, the more effective it is in modifyin g behavior. This is an extremely effective approach because it lets children know what they are doing correctly. Negative reinforcement This is increasing a behavior by removing a negativestimulus. For example, children will compl ete work more quickly so they can go to the playground sooner. Rather than using negative reinforcement, teachers should determine whether the behavior children are trying to avoid could be made more meaningful and interesting. Token economy

- 32. Children's appropriate behavior is rewarded immediately with tokens, which are exchanged for material reinforcers or privileges. Tokens must be exchanged for things students really want; a choice should also be provided. Many believe tokens do not work with children under age 5. Intrinsic reinforcement Intrinsic reinforcement comes from within the child: feelings of success or happiness, or a sense of competence or pride. The ultimate goal of discipline and guidance is that they are internalized. Some people believe using extrinsic reinforcers reduces the power of intrinsic reinforcement. Punishments Natural consequences This is the natural result of what a child does or does not do. A child who forgets to put on a jacket will get cold on a winter day. A child who comes late to the meal may miss out on his or her favorite food. This works only when adults are willing to let go, and to let the child live with the consequences of his or her behaviors. A child needs to be able to make the connection between the behavior and the result. Logical consequences If a child spills milk, a logical consequence is to have him or her clean up the mess; a logical consequence for a child drawing on a table is to have him or her scrub the table clean. The focus should be on fixing the problem and not on the punishment. The child must be able to see how he or she caused the problem and how the action helps to fix it. Unrelated consequence A child who does not complete a math assignment is prevented from playing on the playground. There is no logical connection between the behavior and the consequence.

- 33. This approach should be avoided as much as possible, because it does not teach anything and can backfire. Response cost A child's inappropriate behavior is punished by removing a privilege he or she has earned. For example, a child may earn money for a task and then have it taken away for disobeying. This approach is most effective when combined with positive reinforcement for appropriate behavior, and when the child does not lose everything he or she has earned. Verbal reprimands This is a verbal response by the adult to the child's inappropriate behavior. The response should not be sarcastic, in anger, or degrading. It should inform the child of how he or she can engage in the appropriate behavior. Verbal reprimands are more effective when they are brief, immediate, and accompanied by eye contact or a firm grip. They should be softly spoken and include a statement acknowledging that the child is capable of exhibiting the appropriate behavior. Time out This is a punishment that removes a child from a pleasurable, engaging, or enjoyable situation. The setting should not be reinforcing and the duration of the punishment should be quite short. Time out should be used sparingly and at the highest end of a behavioral continuum. If it ends up being used frequently, it is not working. Modeling Modeling is a very powerful way to teach both appropriate and inappropriate behaviors. It works by the child observing an adult or child who has prestige and competence in a certain behavior or skill. Adults and children whom other children see as behavioral and learning models must be extremely consistent in their behaviors. It is ineffective to say, "Do as I say, not as I do!"

- 34. Wardle, F. (2013). Collaboration with families and communities [Electronic version]. Retrieved from https://content.ashford.edu/