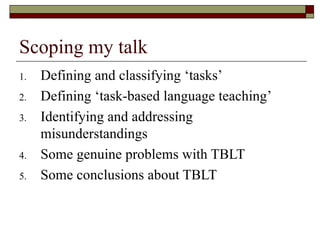

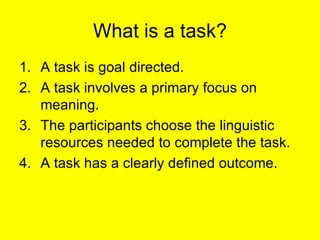

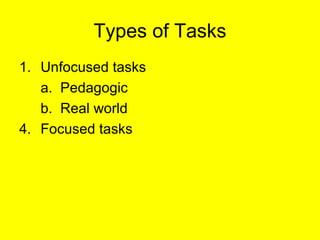

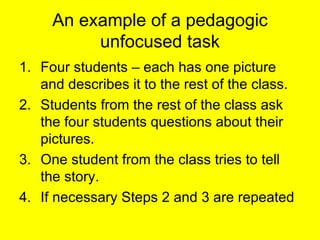

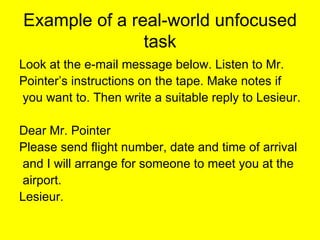

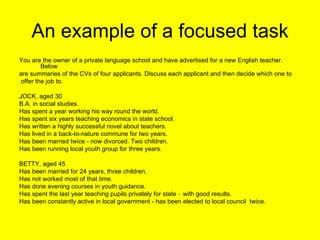

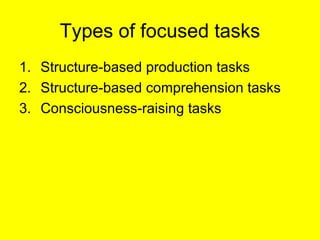

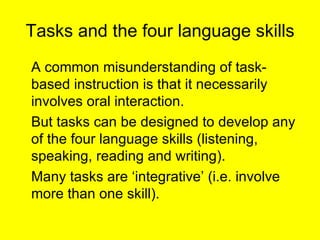

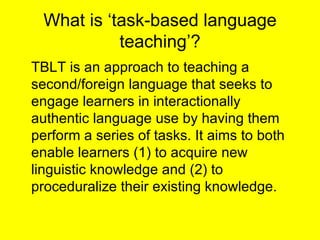

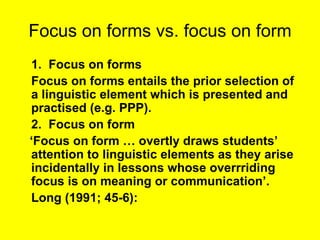

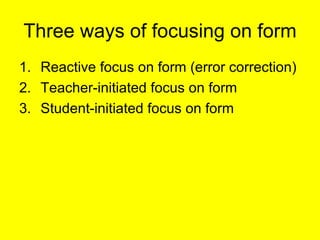

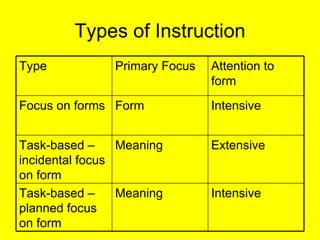

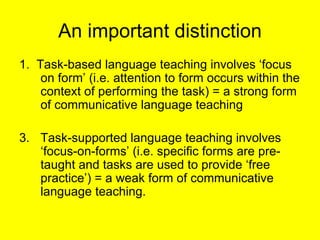

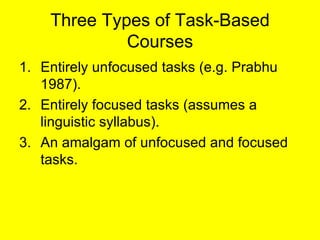

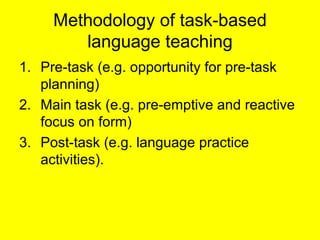

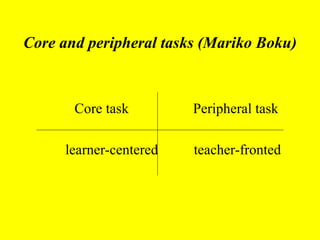

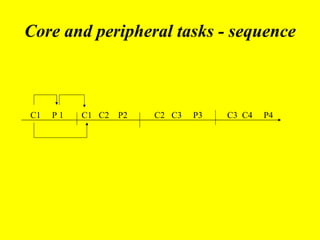

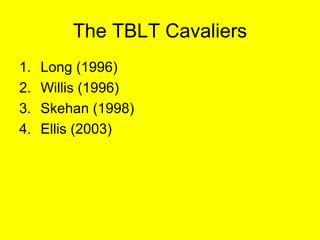

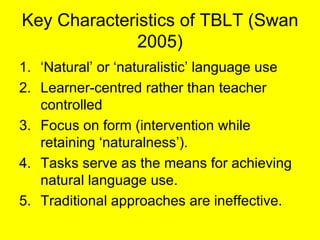

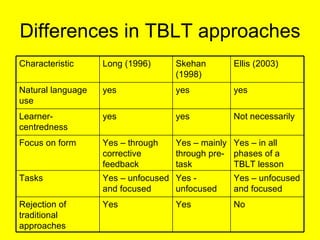

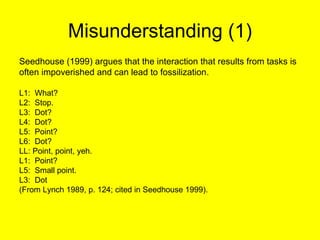

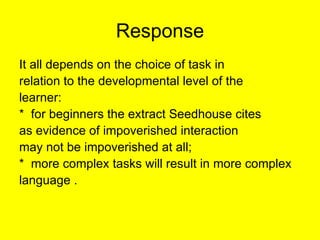

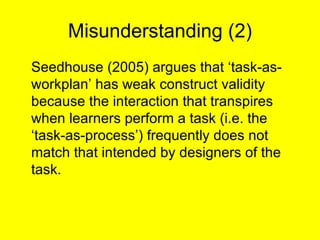

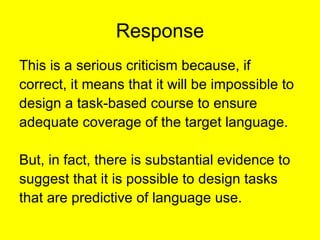

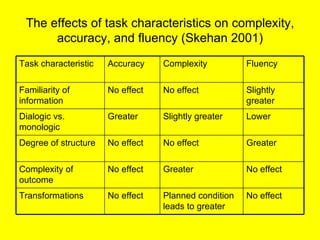

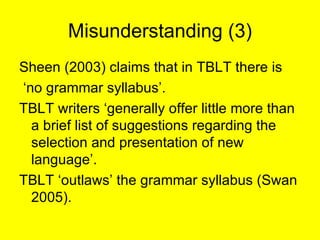

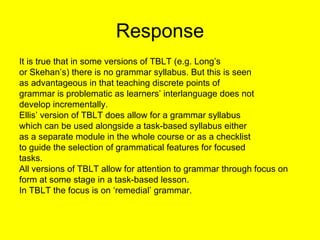

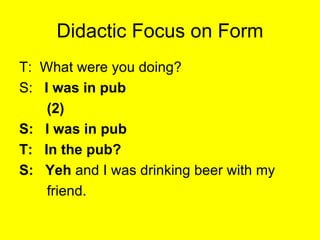

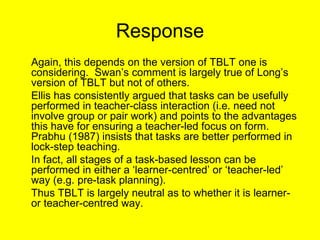

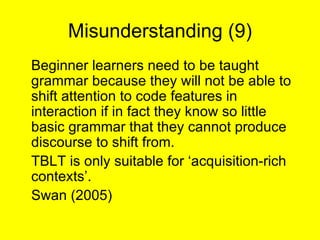

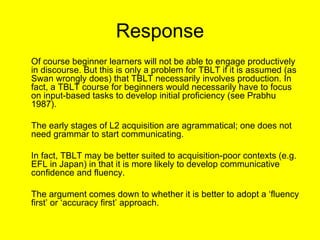

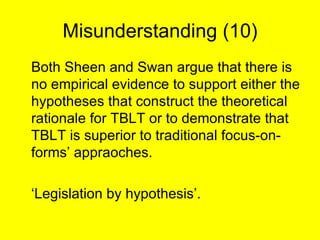

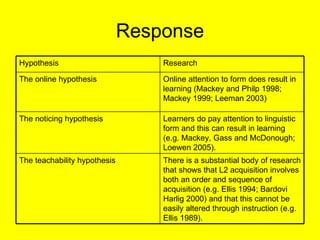

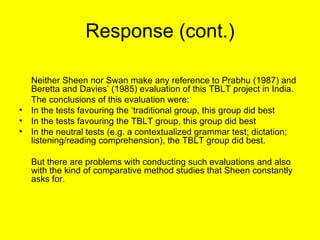

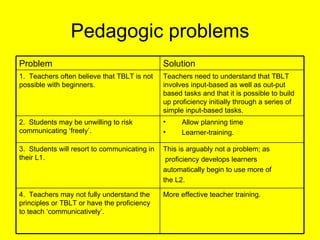

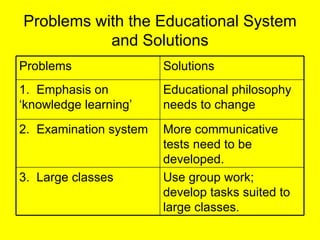

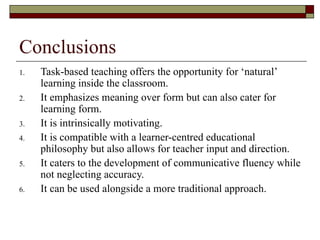

This document summarizes Rod Ellis's talk on task-based language teaching, addressing common misunderstandings about the approach. It defines tasks and discusses different types of tasks. It also defines task-based language teaching and compares it to a focus on forms. The document addresses six misunderstandings critics have about task-based language teaching, such as claims that interaction in tasks is often impoverished or that it does not allow for a grammar syllabus. It provides responses explaining how task design can impact interaction quality and how different versions of task-based language teaching incorporate grammar instruction.