Can the United States Continue to Run Current Account Deficits Ind.docx

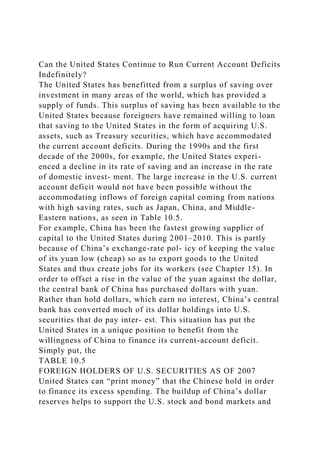

- 1. Can the United States Continue to Run Current Account Deficits Indefinitely? The United States has benefitted from a surplus of saving over investment in many areas of the world, which has provided a supply of funds. This surplus of saving has been available to the United States because foreigners have remained willing to loan that saving to the United States in the form of acquiring U.S. assets, such as Treasury securities, which have accommodated the current account deficits. During the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, for example, the United States experi- enced a decline in its rate of saving and an increase in the rate of domestic invest- ment. The large increase in the U.S. current account deficit would not have been possible without the accommodating inflows of foreign capital coming from nations with high saving rates, such as Japan, China, and Middle- Eastern nations, as seen in Table 10.5. For example, China has been the fastest growing supplier of capital to the United States during 2001–2010. This is partly because of China’s exchange-rate pol- icy of keeping the value of its yuan low (cheap) so as to export goods to the United States and thus create jobs for its workers (see Chapter 15). In order to offset a rise in the value of the yuan against the dollar, the central bank of China has purchased dollars with yuan. Rather than hold dollars, which earn no interest, China’s central bank has converted much of its dollar holdings into U.S. securities that do pay inter- est. This situation has put the United States in a unique position to benefit from the willingness of China to finance its current-account deficit. Simply put, the TABLE 10.5 FOREIGN HOLDERS OF U.S. SECURITIES AS OF 2007 United States can “print money” that the Chinese hold in order to finance its excess spending. The buildup of China’s dollar reserves helps to support the U.S. stock and bond markets and

- 2. permits the U.S. government to incur expenditure increases and tax reductions without increases in domestic U.S. interest rates that would otherwise take place. However, some analysts are con- cerned that at some point Chinese investors may view the increasing level of U.S. foreign debt as unsustain- able or more risky and thus suddenly shift their capital elsewhere. They also express concern that the United States will become more politically reliant on China who might use its large holdings of U.S. securities as leverage against policies it opposes. Can the United States run current account deficits indefinitely and thus rely on inflows of foreign capital? Since the current account deficit arises mainly because foreigners desire to purchase American assets, there is Chapter 10 361 Billions of Country Dollars Japan $1,197 Percent of World Total 12.2% 9.4 9.4 7.6 7.2 4.9 4.0 45.3 100.0% China United Kingdom Cayman Islands Luxembourg Canada Belgium Other 4,418 World Total $9,772 922 921 740 703 475 396

- 3. Source: U.S. Treasury Department, Report on Foreign Portfolio Holdings of U.S. Securities as of June 30, 2007, April 2008, p. 8. Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 362 The Balance of Payments no economic reason why it cannot continue indefinitely. As long as the investment opportunities are large enough to provide foreign investors with competitive rates of return, they will be happy to continue supplying funds to the United States. Simply put, there is no reason why the process cannot continue indefinitely: no automatic forces will cause either a current account deficit or a current account surplus to reverse. United States history illustrates this point. From 1820 to 1875, the United States ran current account deficits almost continuously. At this time, the United States was a relatively poor (by European standards) but rapidly growing country. Foreign investment helped foster that growth. This situation changed after World War I. The United States was richer, and investment opportunities were more limited. Thus, current account surpluses were present almost continuously between 1920 and 1970. During the last 25 years, the situation has again reversed. The current account deficits of the United States are underlaid by its system of secure property rights, a stable political and monetary environment, and a rapidly growing labor force (compared with Japan and Europe), which make the United States an attractive place to invest. Moreover, the U.S. saving rate is low compared to its major trading partners. The

- 4. U.S. current account deficit reflects this combination of factors, and it is likely to continue as long as they are present. At the turn of the century, the United States’ current account deficit was high and rising. By 2006, the U.S. current account deficit was about six percent of GDP, the highest in the country’s history. Even in the late 1800s, after the Civil War, the U.S. deficit was generally below three percent of GDP. During the budget deficits of President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the current account deficit peaked at 3.4 per- cent of GDP. Because of relatively good prospects for growth in the United States compared to the rest of the world, international capital was flowing to the United States in search of the safety and acceptable returns offered there. However, capital was not flowing to emerging markets as in the 1990s. Europe faced high unemploy- ment and sluggish growth, and Japan faced economic contraction and continuing financial problems. Not surprisingly in this setting, capital flowed into the United States because of the relatively superior past performance and expectations for future growth in the U.S. economy. Simply put, the U.S. current account deficit reflected a surplus of good investment opportunities in the United States and a deficit of growth prospects elsewhere in the world. However, many economists feel that economies become overextended and hit trouble when their current-account deficits reach four to five percent of GDP. Some economists think that because of spreading globalization, the pool of savings offered to the United States by world financial markets is deeper and more liquid than ever. This pool allows foreign investors to continue furnishing the U.S. with the money it needs without demanding higher interest rates in return. Presum- ably, a current account deficit of six percent or more of GDP would not have been readily fundable several decades ago. The ability to move that much of world saving to the United States in response to relative rates of return would have been hindered by a far lower degree of international financial interdependence. However, in recent years, the increasing integration of financial markets has created an

- 5. expanding class of foreigners who are willing and able to invest in the United States. The consequence of a current account deficit is a growing foreign ownership of the capital stock of the United States and a rising fraction of U.S. income that must be diverted overseas in the form of interest and dividends to foreigners. A serious Copyright 2010 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. problem could emerge if foreigners lose confidence in the ability of the United States to generate the resources necessary to repay the funds borrowed from abroad. As a result, suppose that foreigners decide to reduce the fraction of their saving that they send to the United States. The initial effect could be both a sudden and large decline in the value of the dollar as the supply of dollars increases on the foreign-exchange market and a sudden and large increase in U.S. interest rates as an important source of saving was withdrawn from financial markets. Large increases in interest rates could cause problems for the U.S. economy as they reduce the market value of debt securities, cause prices on the stock market to decline, and raise questions about the solvency of various debtors. Simply put, whether the United States can sustain its current account deficit over the foreseeable future depends on whether foreigners are willing to increase their investments in U.S. assets. The current account deficit puts the economic fortunes of the United States partially in the hands of foreign investors. However, the economy’s ability to cope with big current account deficits depends on continued improvements in efficiency and technology. If the economy becomes more productive, then its real wealth may grow fast enough to cover

- 6. its debt. Opti- mists note that robust increases in U.S. productivity in recent years have made its current account deficits affordable. But if productivity growth stalls, the economy’s ability to cope with current account deficits will deteriorate. Although the appropriate level of the U.S. current account deficit is difficult to assess, at least two principles are relevant should it prove necessary to reduce the deficit. First, the United States has an interest in policies that stimulate foreign growth, because it is better to reduce the current account deficit through faster growth abroad than through slower growth at home. A recession at home would obviously be a highly undesirable means of reducing the deficit. Second, any reductions in the deficit are better achieved through increased national saving than through reduced domestic investment. If there are attractive investment opportunities in the United States, we are better off borrowing from abroad to finance these opportunities than forgoing them. On the other hand, incomes in this country would be even higher in the future if these investments were financed through higher national saving. Increases in national saving allow interest rates to remain lower than they would otherwise be. Lower interest rates lead to higher domestic investment, which, in turn, boosts demand for equipment and construction. For any given level of investment, increased saving also results in higher net exports, which would again increase employment in these sectors. However, shrinking the U.S. current account deficit can be difficult. The econo- mies of foreign nations may not be strong enough to absorb additional American exports, and Americans may be reluctant to curb their appetite for foreign goods. Also, the U.S. government has shown a bias toward deficit spending. Turning around a deficit is associated with a sizable fall in the exchange rate and a decrease in output in the adjusting country, topics that will be discussed in subsequent chapters.

- 7. In te rn at io na lt op ic s E co no m ic s Editor Stefan Schneider +49 69 910-31790 [email protected] Technical Assistant Pia Johnson +49 69 910-31777 [email protected]

- 8. Deutsche Bank Research Frankfurt am Main Germany Internet: www.dbresearch.com E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +49 69 910-31877 Managing Director Norbert Walter October 1, 2004 Current Issues The U.S. balance of payments: wide- spread misconceptions and exaggerated worries • The U.S. balance of payments is by far the most confusing and least understood area of the U.S. economy. The confusion is centered around the large and rapidly growing deficits. Indeed, the deficit on the current account of the balance of payments rose to new records, both in absolute and relative terms. • These developments created worries and fears regarding the sustainability of the external deficits. However, closer examination of the issue shows that the worries and fears are exaggerated and, most importantly, there are no short- and medium-term solutions because of a number of structural reasons. Mieczyslaw Karczmar, +1 212 586-3397 ([email protected])

- 9. Economic Adviser to DB Research Guest authors express their own opinions, which may not necessarily be those of Deutsche Bank Research. October 1, 2004 Current Issues Economics 3 The U.S. balance of payments is by far the most confusing and least understood area of the U.S. economy. The confusion is centered around the large and rapidly growing deficits. Indeed, the deficit on the current account of the balance of payments rose from USD 474 billion in 2002 to USD 531 billion in 2003 and is estimated to reach over USD 600 billion in 2004 (see table 1). In relative terms, the deficits amount to 4.5%, 4.9% and 5.3% of GDP, respectively, in those years. Both in absolute and relative terms, these are all- time records. The sustainability of external deficits Persistent and rising external deficits have attracted increasing at- tention of politicians, economists and the media. Needless to say,

- 10. the deficits are generally viewed as highly negative for the U.S. economy and U.S. financial conditions. The main points of concern are: • Rising foreign indebtedness that might create financial difficulties over time. • A potential massive dollar depreciation needed to rectify the situation. • In an extreme case, a financial crisis as foreigners refuse to fi- nance U.S. deficits and switch their capital to other places. The media, regardless of their political outlook, have been commenting on the U.S. external deficits for quite some time, spreading fear and predicting all sorts of calamities, which apparently sells newspapers well. About five years ago, in the fall of 1999, The New York Times ran an article with a pointed headline: “The United States sets a record for living beyond its means;” and a Barron’s article talked about a current account crisis and a ticking time bomb. Had these scary predictions materialized, the U.S would have been bankrupt by now. But never mind, the fascination with the rising deficits continues. A Financial Times article a few weeks ago was headlined: “America is now on the comfortable path to ruin.” The persistence of external deficits and their presumable negative effects have focused the economic debate on the key question.

- 11. Are the deficits sustainable? A generally uniform answer is that not, that they are not sustainable. The Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan has repeatedly emphasized that he does not believe the deficits can go on indefinitely. But he confessed that he does not know when will they stop. And he admitted that so far the financial markets have coped very well with the global payments imbalances. The late Herbert Stein, a great economist with a great sense of hu- mor, had famously said that if something cannot go on forever, it will stop. The logic of this reasoning is unassailable. However, 2004 will be the 29th consecutive year of trade deficits and (disregarding the statistical aberration in 1991 when foreign contributions to finance the Gulf war produced a small surplus) the 23rd consecutive year of current-account deficits. But during this period, the U.S. enjoyed a generally prosperous economy, especially during the decade of the 1990s when the economy went through an unprecedented boom. So maybe Stein’s saying should be reversed – if a trend goes on for a long time, and it not only does not have any harmful effects but, on the contrary, coincides with a period of prosperity, it may well be sustainable.

- 12. One-liners aside, there is an apparent conflict between theory and empirical evidence. To address the contradiction between theoretical and empirical considerations, it is necessary to examine the Scary media predictions have so far not materialised -6.0 -5.5 -5.0 -4.5 -4.0 -3.5 -3.0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 -700 -600 -500 -400 -300 -200

- 13. -100 0 Current account USD bn (right) % GDP (left) -600 -500 -400 -300 -200 -100 0 100 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 Current account & trade balance Current account USD bn Trade balance

- 14. Current Issues October 1, 2004 4 Economics following key aspects of the U.S. balance of payments: a) the nature and underlying causes of the deficits, b) the financing of the deficits, c) main characteristics of U.S. foreign debt, and d) the role of the dollar in dealing with the external deficits. Main characteristics of U.S. external deficits When analyzing the external deficits, it is essential to distinguish between cyclical and structural deficits. The cyclical deficits are non-controversial and easy to understand. They result from the disparity in economic growth between the U.S. and its main trading partners, with the U.S. showing stronger growth. This generates increased demand for imports while U.S. exports are hampered by slower growth abroad. Over the past 20 years, the U.S. has shown generally strong eco- nomic performance (except for two brief and shallow recessions in 1991 and 2001), superior to most other industrial countries. It is, therefore, not surprising that this coincided with rising trade and current-account deficits. Indeed, while in 1983 the current-

- 15. account deficit amounted to 1.1% of GDP, it has risen to about 5% in the last two years. How long this strongly rising deficit trend would last? It is difficult to predict with any certainty. Yet, although the trend has been cyclically driven, it has certain permanent characteristics rooted in demo- graphic and productivity aspects. First, the U.S. is the only major industrial country with growing popu- lation. The latest census in 2000 has shown that during the decade of the 1990s U.S. population grew by 13.2%, in contrast with stag- nating or shrinking populations elsewhere in the industrial world. Moreover, although the U.S. population is aging, it is aging less than in other main industrial countries – the census revealed, e.g., that 72.7% of U.S. population was below the age of 50, while the number of people in the 35-54 age range, the most productive and highest spending segment, increased by 32% in the previous decade. Second, the technological revolution of the 1990s was most pronounced in the U.S. as it was in America where the Schumpeterian “creative destruction” took mostly place. This led to strong productivity gains, superior to those in most other nations. The combination of population and productivity growth resulted in a rising growth potential of the economy. Even allowing for the

- 16. most recent slowdown in productivity growth, potential annual growth of the U.S. economy is still estimated at about 3.5%, i.e. about 1% higher than in Europe. To be sure, there has been an acceleration of the economic expan- sion in Japan (even allowing for the most recent slowdown) and continuing strong growth in China and the Asian newly industrialized countries (NIC). This should boost U.S. exports and possibly arrest the inexorable widening of U.S. deficits. But eliminating them, let alone turning them around into surpluses, is out of the question in the foreseeable future. The reasons lie in the structural deficits. The structural deficits draw much less attention than the cyclical ones, even though they are at least equally important. Even if the disparity in economic growth rates between the U.S. and the rest of the world were eliminated, the U.S. would still have trade and current-account deficits for the following main reasons. First, U.S. income elasticity of imports is higher than foreign income elasticity for U.S. exports. This phenomenon is rooted in the general openness of the U.S. market, which makes imported goods readily available and it makes them available at increasingly competitive U.S. has exceptionally high income elasticity of imports

- 17. -600 -500 -400 -300 -200 -100 0 100 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 Current account & real GDP Current account (right)

- 18. USD bn Real GDP (left) % yoy -4 -2 0 2 4 6 8 10 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 Nonfarm productivity % yoy October 1, 2004 Current Issues Economics 5

- 19. prices. Moreover, the development of industrial cooperation and outsourcing has increased sharply income elasticity of imports, as some products or groups of products are no longer produced in the U.S. While traditionally the ratio of import growth to GDP growth was about 1.7, it is now closer to 2.5 –3.0. Second, the proliferation of outsourcing, beginning with the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) 10 years ago, and now extended to India, China and other Asian countries, has almost by definition widened the U.S. trade deficit as US products shipped abroad return to the US with value added; hence, the value of im- ports exceeds that of exports. Third, the U.S. dollar’s function as the main reserve currency makes the current-account deficit inevitable because of (a) inflow to the U.S. of monetary reserves of foreign central banks due to the normal accumulation of these reserves, especially in countries with current- account surpluses, and (b) occasional interventions in foreign ex- change markets by countries trying to resist the appreciation of their currencies vis-à-vis the U.S. dollar. Of course, this source of financing the U.S. current-account deficits is not guaranteed forever. It is hoped that eventually the euro will also become a main reserve currency, which would in fact fulfill

- 20. de Gaulle’s idea of breaking the dollar’s hegemony that was at the foundation of the concept of a single European currency. But this is not likely to happen in the near future. The dollar is still the dominant reserve currency as about 65% of global monetary reserves are held in dollars. The financing of U.S. external deficits It is an axiom of the foreign trade theory that a country can run a balance of payments deficit only to the extent it can finance it, either through borrowing or through depleting its foreign exchange reserves. In this respect, the U.S. is in an exceptionally advantageous situa- tion because it does not need to borrow in a conventional sense. The financing comes voluntarily because of the attractiveness of the U.S. as an investment destination providing generally higher rates of return than obtainable elsewhere; because of the seize, scope, openness and liquidity of the U.S. capital markets; and because of the dollar’s role as the world’s prime investment, transaction and reserve currency. Interest rates are determined by the conditions in the U.S. money and capital market rather than dictated by the lend- ers. And, unlike most other countries, the U.S. has the ability to fi- nance its external deficits in its own currency.

- 21. There is no doubt that this relative easiness in financing is an impor- tant factor in sustaining the US trade and current-account deficits. Some economists go even further. They contend that it is the financ- ing side of the equation, or net capital inflow, that determines the current-account deficits. For example, Milton Friedman – in an inter- view earlier this year – when asked about the reason for the U.S. current-account deficit, responded that it is because foreigners want to invest in the U.S. This view was postulated by the Austrian economist Böhm-Bawerk a good 100 years ago, stating that it is the capital account of the balance of payments which leads the current account. This view is also represented by William Poole, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. In a paper published in the January/February 2004 issue of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, Poole – drawing on research of Catherine Mann from the Institute for International Economics in Washington – examines 2 4 6 8

- 22. 10 12 14 16 80 82 84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 10Y Govt. bond yields % USA Germany Current Issues October 1, 2004 6 Economics three different views of the U.S. international imbalance: (a) the trade view, in which trade flows are the primary factors and the offsetting capital inflows are secondary, (b) the GDP view, in which the current-account deficit is perceived as a shortfall between domestic investments and domestic savings, and (c) the capital flows view, in which the trade and current-account deficits are a residual, the result of the capital-account surplus. This surplus, in turn, is driven by foreign demand for U.S. assets rather than by any structural imbalance in the U.S. economy. Needless to say, the capital flow view is the most amenable to the

- 23. sustainability of the U.S. external deficits. There is a legitimate concern voiced by some economists that – due to persistent foreign demand for U.S. assets – the U.S. has absorbed some 80% of international savings in recent years. This may cause a U.S. dollar overweight in global portfolios. However, there is no solution in sight for this apparent asymmetry in portfolio allocations. The financing of U.S. external deficits is an area of the greatest mis- conceptions. A popular view held by some economists and the me- dia is that foreign investors might refuse to finance the U.S. deficits and switch their capital to other places or invest in their own coun- tries, which could have dire consequences for the U.S. This may indeed happen. But one should keep in mind that foreigners invest in the U.S. because they view this as advantageous for them, not to do America a favor. Granted, they may decide to increase their domestic investments. But as long as the U.S. has a large current-account deficit and Japan, China and other countries have large surpluses, continuing capital inflow to the U.S. is assured. It is also true that foreign countries may shift some of their monetary reserves to other places. But as long as the U.S. dollar remains the pre-eminent reserve currency, this is unlikely because of the limited size and scope of other monetary areas. The situation illustrates the

- 24. “exorbitant privilege” – in de Gaulle’s words some 45 years ago – the U.S. derives from the dollar’s global role. This enables the U.S. to run “deficits without tears” as described by Jacques Rueff, de Gaulle’s adviser. In short, if someone argues that at some point foreigners might re- fuse to continue financing U.S. external deficits, a question must be answered – where would they go with their money. The alternatives to investing in the U.S. are very limited, indeed. The U.S. international indebtedness A very important issue in assessing the sustainability of the U.S. external deficits is the magnitude and structure of U.S. foreign indebtedness, as reflected in annual Commerce Department reports on U.S. international investment position (see table 2).1 As can be seen, net indebtedness reached at the end of 2003 USD 2.4 trillion or USD 2.6 trillion (depending on the valuation method of U.S. and foreign direct investments), i.e. close to 25% of GDP, up from a rough equilibrium in 1989. This has caused widespread lam- entations that the U.S., the richest country in the world, has become within 15 years the biggest debtor in the world. 1 U.S. international investment position does not exactly

- 25. represent U.S. foreign debt, since it also includes equities and physical capital, but it is a good proxy of the U.S. in- ternational indebtedness. Current-account deficit can be financed by a “structural surplus” in the capital account Lack of alternative locations for investment October 1, 2004 Current Issues Economics 7 Such a sharp rise in foreign debt should not be surprising, considering the piling up of current-account deficits in recent years. What is surprising, though, is that the investment income/payments balance has been in surplus (see table 1) despite the large and rising debt. How to explain this apparent incongruity? The main reason for the surplus in investment income despite the rising U.S. indebtedness is that U.S. investments abroad are, in aggregate, more profitable than foreign investments in the United States. This fact is primarily caused by a very large share of foreign official assets in the U.S. due to the dollar’s function as the main

- 26. reserve currency. (Private capital flows, as mentioned before, have an oppo- site characteristic as foreigners generally enjoy a higher return on their investments in the U.S.) As can be seen from table 2 (item 18), foreign official assets in the U.S. reached USD 1.5 trillion at the end of last year, i.e. 60% or 55% of U.S. net indebtedness (depending on the valuation method of direct investments). In allocating their monetary reserves, foreign central banks are primarily motivated by safety and liquidity rather than by the rate of return. They invest these reserves mostly in U.S. Treasury bills, which bring them relatively low returns. In addition, U.S. currency owned by foreigners, which is practically costless, reached USD 318 billion last year (item 27), bringing the total of low- or no-cost U.S. liabilities to about 70% of net U.S. debt. Moreover, foreign official assets and currency have, by a large, a permanent character, similar to demand deposits at commercial banks, further easing the burden of U.S. foreign indebtedness. The balance of payments and the dollar One of the most controversial issues of the U.S. international economy is the relationship between the balance of payments and the dollar exchange rate. Many economists believe that it is the widening of the U.S. current-account deficit that is responsible for

- 27. the dollar decline during the past 2-3 years. Some even go further by saying that it would be impossible to eliminate the deficit without a massive, prolonged devaluation of the dollar. These views are highly questionable. They ignore historic experi- ence and they are based on an obsolete theory. If the weakening dollar is mainly the result of rising external deficits, how to explain the fact that between 1995 and 2001, when the U.S. current- account deficit nearly quadrupled, the dollar was on a strongly rising trend. Going back another 10 years to 1985, the Plaza Hotel Agreement was a major international event aimed at pushing the dollar down, with the main underlying objective of shrinking and eventually eliminating the U.S. current-account deficit. This did not happen, however, and the deficit rose to new highs. The main underlying reason for the weak response of trade flows to the dollar devaluation is the relative low price elasticity of both sides of the U.S. trade balance. On the import side, for the dollar devalua- tion to have a full effect on trade flows, two conditions must be ful- filled: a) foreign exporters have to raise their prices to offset the cur- rency loss, and b) domestic producers competing with imports have to keep their prices constant in order to increase their market share

- 28. and shift demand away from imports to domestic production. None of these conditions is fulfilled to the full extent. Foreign exporters are reluctant to raise their dollar prices in order not to jeopardize their competitive position in the huge and lucrative American market. They often cut their profit margins and sometimes -25 -20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 76 81 86 91 96 01 Net international investment position % GDP 0.00 0.25

- 29. 0.50 0.75 1.00 1.25 70 75 80 85 90 95 00 Balance of investment income % GDP -600 -500 -400 -300 -200 -100 0 100 80 84 88 92 96 00 70 80 90

- 30. 100 110 120 130 140 Current account & USD Current account (right) USD bn USD nominal trade-weighted rate (left) 2000=100 Current Issues October 1, 2004 8 Economics even run temporary losses, all in order to keep their market shares. Labor Department data on import prices clearly show this phenomenon. For the past two years non-oil import prices have risen only marginally. Moreover, even when foreign exporters raise their prices,

- 31. domestic producers competing with imports often raise prices, too, under the umbrella of higher import prices, thus defeating the macro- economic purpose of devaluation. This had happened on a massive scale in the 1985-1995 period when U.S. auto makers did not bother to go for higher market shares; they raised their prices, knowing that Americans will buy Japanese cars anyway because of their superior quality. Interestingly, these are not new phenomena, they have been known for decades. Weak macro-economic effects of currency devaluation were particularly visible during the devaluation of the British pound in 1967. Since that time, if anything, devaluation effects have be- come weaker still as trade flows shifted further away from commod- ity-type trade toward capital equipment. Similarly, on the export side, currency changes and the associated changes in relative prices have had diminishing results on the trade balance. This was especially clear during periods of the dollar ap- preciation in the 1980s and 1990s. It did not hamper U.S. exports, as theoretically expected. On the contrary, exports were running strong since U.S. trade partners were willing to pay higher prices for the U.S. technology, know-how and sophisticated capital goods.

- 32. A separate case is the possible revaluation of the Chinese yuan by eliminating its fixed exchange rate to the dollar. This is strongly ad- vocated by some economists and policymakers in view of the rapidly rising U.S. trade deficits with China. But it is dubious that this would really happen. The exchange rate of the yuan is a political issue rather than an economic one; it is determined by the Chinese Polit- bureau, not by market forces. The dollar decline during the 2001-2004 period cannot be attributed to any large extent to the widening U.S. trade and current- account deficits. The main contributing factors were a) exceptionally wide interest ride differentials between the U.S. and other industrial nations as U.S. rates fell to their lowest levels in over 40 years, b) the September 11 events and constant fears of further terrorist attacks, and c) a change in the attitude of the U.S. toward the dollar as clear signs emerged that the Bush administration is not unhappy with the weaker dollar, in contrast with the strong-dollar policy of the second Clinton administration. All together, a dollar devaluation is not likely to solve the deficit prob- lem (if there is one), and may disappoint those who advocate it. On the contrary, from the policy standpoint, it may have a negative im- pact on the U.S. economy. Considering that it is capital flows

- 33. rather than trade flows that determine the dollar exchange rate, devalua- tion might hamper the financing of the deficit without reducing it to any large extent. Concluding remarks The persistence of U.S. external deficits and the associated rise of U.S. international debt have led to widespread worries and fears as to how long this condition may last and how could it be rectified. Closer examination of this issue shows, however, that the worries are far from justified and the fears greatly exaggerated, for the fol- lowing main reasons: -30 -20 -10 0 10 20 30 40

- 34. 80 82 84 86 88 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 Exports & USD Exports % yoy USD nominal effective exchange rate -20 -15 -10 -5 0 5 10 15 90 92 94 96 98 00 02 04 Import prices & USD Import prices % yoy USD nominal effective exchange rate

- 35. October 1, 2004 Current Issues Economics 9 • The primary cause of U.S. trade deficits is disparity of economic growth, with the U.S. growing faster than most other industrial nations due to demographic and productivity factors. Sure, a deep and protracted recession in America could possibly reverse the rising deficit trend. But, obviously, the cure would be worse than the disease. The U.S. is thus a victim of its own success. The deficit is a reflection of U.S. strength not weakness. • Even when disregarding the growth disparity, the U.S. would still run external deficits for a number of structural reasons, the most important of which are: a) high income elasticity of imports, b) spreading industrial cooperation and outsourcing, c) the dollar’s function as the key global reserve currency. • Although the accumulation of current-account deficits raised U.S. international debt to about one-quarter of its GDP, the structure of the debt is highly advantageous as about 70% of it constitutes liabilities to foreign central banks and U.S. currency owned by foreigners. Both sources have pretty permanent characteristics and, above all, very low cost of financing or are outright costless. • The depreciation of the dollar is not likely to change much the balance of payments deficit but it may jeopardize its financing. So, all together, does the U.S. have a problem with its external deficits? If it does, the problem certainly pales in comparison with

- 36. major long-term problems, such as the unfunded liabilities of the Social Security system in view of the forthcoming retirement of the baby-boom generation, the explosive rise in health-care costs, and the growing dependence on oil imports from volatile areas of the world. Most important, as the paper was trying to demonstrate, if it is a problem, there are no immediate solutions of the problem. And to quote another Herb Stein’s one-liner, “if there is no solution to a problem, there is no problem.” Finally, an important mitigating circumstance is that it is mostly economists and politicians who worry about the external deficits. The general public does not lose sleep over the issue, which only attests to the common sense of the American people. Mieczyslaw Karczmar, +1 212 586-3397 ([email protected]) Economic Adviser to DB Research Current Issues October 1, 2004 10 Economics Table 1: U.S. Balance of Payments (in billions of dollars)

- 37. I. Current Account 2002 2003 2004* Exports of goods 681.8 713.1 791.5 Imports of goods -1164.7 -1260.7 -1400.2 Merchandise Trade Balance -482.9 -547.6 -608.7 Income from services 294.1 307.3 334.3 Payments for services -232.9 -256.3 -283.4 Services Balance 61.2 51.0 50.9 Income from U.S. assets abroad 266.8 294.4 340.8 Payments on foreign assets in the U.S. -259.6 -261.1 -311.2 Investment Income/Payments Balance 7.2 33.3 29.6 Unilateral Transfers -59.4 -67.4 -78.8 Current-Account Balance -473.9 -530.7 -607.0 II. Capital (Financial) Account (private) Foreign direct investment 72.4 39.9 85.8 Foreign portfolio investment 385.9 365.4 503.4 Bank borrowing 96.4 75.6 343.5 Other 99.5 100.7 85.0 Capital inflow 654.2 581.6 1017.7 U.S. direct investment abroad -134.8 -173.8 -216.7 U.S. portfolio investment abroad 15.9 -72.3 -93.7 Bank lending -30.3 -10.4 -436.0 Other -46.4 -32.5 -108.8 Statistical discrepancy -95.0 -12.0 57.3 Capital outflow -290.6 -301.0 -797.9 Capital-Account Balance 363.6 280.6 219.8

- 38. III. Balance of Payments -110.3 -250.1 -387.2 IV. Official Reserve Transactions Decline (+) /Increase (-) in U.S. official reserve assets -3.7 1.5 3.4 Increase in foreign official assets in the U.S. 114.0 248.6 383.8 *) Forecast Source: US Department of Commerce, own calculation and regroupings October 1, 2004 Current Issues Economics 11 Line Type of investment Position, Position 2002r 2003p Net international investment position of the United States: 1 With direct investment positions at current cost (line 3 less line 16).......................................................................................... .....................................................-2,233,018 -2,430,682 2 With direct investment positions at market value (line 4 less line 17).......................................................................................... .....................................................-2,553,407 -2,650,990 U.S.-owned assets abroad: 3 With direct investment at current cost (lines 5+6+7)....................................................................................

- 39. ...........................................................6,413,535 7,202,692 4 With direct investment at market value (lines 5+6+8).................................................................................... ...........................................................6,613,320 7,863,968 5 U.S. official reserve assets...................................................................................... .........................................................158,602 183,577 6 U.S. Government assets, other than official reserve assets...................................................................................... .........................................................85,309 84,772 U.S. private assets: 7 With direct investment at current cost (lines 9+11+14+15)........................................................................... ....................................................................6,169,624 6,934,343 8 With direct investment at market value (lines 10+11+14+15)......................................................................... ......................................................................6,369,409 7,595,619 Direct investment abroad: 9 At current cost......................................................................................... ......................................................1,839,995 2,069,013 10 At market value................................................................................... .... ........................................................2,039,780 2,730,289 11 Foreign securities................................................................................ ...............................................................1,846,879 2,474,374

- 40. 12 Bonds..................................................................................... ..........................................................501,762 502,130 13 Corporate stocks..................................................................................... ..........................................................1,345,117 1,972,244 14 U.S. claims on unaffiliated foreigners reported by U.S. nonbanking concerns............................................................................. ..... .............................................................908,024 614,672 15 U.S. claims reported by U.S. banks, not included elsewhere................................................................................ ...............................................................1,574,726 1,776,284 Foreign-owned assets in the United States: 16 With direct investment at current cost (lines 18+19).................................................................................... ...........................................................8,646,553 9,633,374 17 With direct investment at market value (lines 18+20).................................................................................... ...........................................................9,166,727 10,514,958 18 Foreign official assets in the United States...................................................................................... .........................................................1,212,723 1,474,161 Other foreign assets: 19 With direct investment at current cost (lines 21+23+24+27+28+29).............................................................. .................................................................................7,433,83 0 8,159,213 20 With direct investment at market value (lines 22+23+24+27+28+29)..............................................................

- 41. .................................................................................7,954,00 4 9,040,797 Direct investment in the United States: 21 At current cost......................................................................................... ......................................................1,505,171 1,553,955 22 At market value....................................................................................... ........................................................2,025,345 2,435,539 23 U.S. Treasury securities................................................................................ ...............................................................457,670 542,542 24 U.S. securities other than U.S. Treasury securities................................................................................ ...............................................................2,786,647 3,391,050 25 Corporate and other bonds...................................................................................... .........................................................1,600,414 1,852,971 26 Corporate stocks..................................................................................... ..........................................................1,186,233 1,538,079 27 U.S. currency.................................................................................. .............................................................301,268 317,908 28 U.S. liabilities to unaffiliated foreigners reported by U.S. nonbanking concerns.................................................................................. .............................................................864,632 466,543 29 U.S. liabilities reported by U.S. banks, not included elsewhere................................................................................ ...............................................................1,518,442 1,887,215 p Preliminary.

- 42. r Revised. Source: US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis Table 2: International Investment Position of the United States at Yearend, 2002 and 2003 [Millions of dollars] Current Issues ISSN 1612-314X Topics published on The U.S. balance of payments: widespread misconceptions October 1, 2004 and exaggerated worries Japanese cars: sustainable upswing expected September 27, 2004 Asia outlook: cruising at a good speed September 14, 2004 Foreign direct investment in China - August 24, 2004 good prospects for German companies? Germany on the way to longer working hours August 10, 2004 Steel market in China: Constraints check more powerful growth August 6, 2004 Global outlook: above-trend growth to continue in 2005 July 27, 2004

- 43. Innovation in Germany - Windows of opportunity June 22, 2004 Consolidation in air transport: in sight at last? June 16, 2004 Privatisation and regulation of German airports Credit derivatives: effects on the stability of financial markets June 9, 2004 Demographic developments will not spare the public infrastructure June 7, 2004 Infrastructure as basis for sustainable regional development June 3, 2004 Available faster by e-mail!!! © 2004. Publisher: Deutsche Bank AG, DB Research, D-60262 Frankfurt am Main, Federal Republic of Germany, editor and publisher, all rights reserved. When quoting please cite “Deutsche Bank Research“. The information contained in this publication is derived from carefully selected public sources we believe are reasonable. We do not guarantee its accuracy or completeness, and nothing in this report shall be construed to be a representation of such a guarantee. Any opinions expressed reflect the current judgement of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Deutsche Bank AG or any of its subsidiaries and affiliates. The opinions presented are subject to change without notice. Neither Deutsche Bank AG nor its subsidiaries/affiliates accept any responsibility for liabilities arising from use of this document or its contents. Deutsche Banc Alex Brown Inc. has accepted responsibility for the distribution of this report in the United States under applicable requirements. Deutsche Bank

- 44. AG London being regulated by the Securities and Futures Authority for the content of its investment banking business in the United Kingdom, and being a member of the London Stock Exchange, has, as designated, accepted responsibility for the distribution of this report in the United Kingdom under applicable requirements. Deutsche Bank AG, Sydney branch, has accepted responsibility for the distribution of this report in Australia under applicable requirements. Printed by: Druck- und Verlagshaus Zarbock GmbH & Co. KG ISSN Print: 1612-314X / ISSN Internet and ISSN E-mail: 1612-3158 All our publications can be accessed, free of charge, on our website www.dbresearch.com. You can also register there to receive our publications regularly by e-mail. Ordering address for the print version: Deutsche Bank Research Marketing 60272 Frankfurt am Main Fax: +49 69 910-31877 E-mail: [email protected] October 1, 2004The U.S. balance of payments: widespread misconceptions and exaggerated worriesCI- 24092004karczmar_doc9.pdfOctober 1, 2004The U.S. balance of payments: widespread misconceptions and exaggerated worries