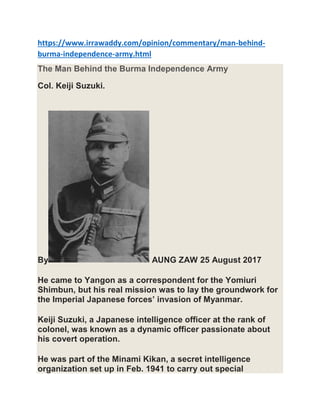

THE MAN BEHIND THE BURMA INDEPENDENCE-ARMY COL KEIJI SUZUKI

- 1. https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/commentary/man-behind- burma-independence-army.html The Man Behind the Burma Independence Army Col. Keiji Suzuki. By AUNG ZAW 25 August 2017 He came to Yangon as a correspondent for the Yomiuri Shimbun, but his real mission was to lay the groundwork for the Imperial Japanese forces’ invasion of Myanmar. Keiji Suzuki, a Japanese intelligence officer at the rank of colonel, was known as a dynamic officer passionate about his covert operation. He was part of the Minami Kikan, a secret intelligence organization set up in Feb. 1941 to carry out special

- 2. operations—a household name among former soldiers who once fought in Myanmar’s independence struggle. In 1940, Col Suzuki took the name Minami Masuyo and arrived in Yangon, where his colleagues set up a secret office at 40 Judah Ezekiel Street and established contacts with young nationalists in Myanmar. Suzuki was described as “genuinely concerned” for countries in Asia colonized by Europeans. The Japanese colonel, who was dubbed “Asia’s Lawrence of Arabia,” attended Japan’s prestigious General Staff College, spoke fluent English, and was known to identify with independence struggles throughout the continent. Recruitment of Young Nationalists The Japanese Imperial Army, however, had no interest in saving Myanmar from the British: the Japanese wanted to cut off the Burma Road, through which the British were sending military assistance, supplies and weapons to China. Before coming to Yangon, Keiji Suzuki developed connections with prominent members of Myanmar’s thakin movement —nationalist activists and students pushing for Myanmar’s independence—as well as those living in Japan.

- 3. A selection of members of the Thirty Comrades. Front row, from left to right: Bo Zeya, Bo Aung, Nagai, Bo Teza, Bo Moegyo, Bo Ne Win, and Bo La Yaung. (Photo: Public Domain) The irony is that the thakins—meaning “masters,” to indicate that they were masters of their own nation—found that they

- 4. had more in common with the Chinese nationalists than Japanese militarists. In fact, many progressive, educated and left-leaning thakins, including young Thakin Aung San, father of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, did not agree with what Japanese forces had done in their invasion of China. However, they were pragmatic, and that played a major role in their quest for independence. To achieve this, Myanmar nationalists were ready to accept assistance from any quarter. Meanwhile, the Japanese propaganda machine was in full swing in British-occupied Myanmar; Japan’s slogan of “Asia for Asians” intersected with growing anti-British sentiment in the country. In Yangon, Col Suzuki met Myanmar nationalists who were willing to take up arms. They were naïve, but idealistic and committed. A decade later, those young nationalists became prominent politicians and independence heroes. Aung San—already a leading figure in the underground movement—was contemplating armed struggle to regain independence, but would require outside assistance. A fugitive from the British authorities, Aung San left Myanmar secretly to seek help abroad. According to the book “Burma and Japan Since 1940,” by Donald M. Seekins, the then head of the Japan-Burma Friendship Society Dr. Thein Maung said that a Japanese diplomat planned Aung San’s escape to Amoy, now known as Xiamen, in southern China.

- 5. In her biography of her father, “Aung San of Burma,” Daw Aung San Suu Kyi wrote that his original intentions were to procure support from communists in China, and not from Japan. In any case, Aung San and a colleague, Than Myaing, were stranded for months in Amoy. Suzuki sent out Japanese agents to rescue the duo and fly them to Tokyo. In Tokyo, Aung San made the decision to work with the Japanese. Dr. Maung Maung, a subordinate and biographer of Gen Ne Win, interviewed 62-year-old Keiji Suzuki at his home in Hamamatsu, Japan in the 1950s. He wrote of Suzuki’s account of Aung San and Than Myaing’s arrival in Tokyo in November: they were dressed only in summer clothes and had no passports. He told Dr. Maung Maung that among Myanmar nationalists there were two schools of thought on seeking foreign aid: one was to form an alliance with China or Russia, and another favored Japan. The first group was in the majority, he believed. Suzuki’s observation of Aung San was that he was honest and brave, but that the then 25-year-old lacked maturity. He asked Aung San to draft a blueprint for a free Burma. Some scholars later questioned whether the blueprint that was forwarded to the Japanese headquarters was originally written by Aung San, or whether it had been modified by Suzuki in an effort to please his superiors. The young Aung San learned to wear Japanese traditional clothing, speak the language, and even took a Japanese name. In historian Thant Myint-U’s “The River of Lost

- 6. Footsteps,” he describes him as “apparently getting swept away in all the fascist euphoria surrounding him,” but notes that his commitment remained to independence for Myanmar. Aung San (right) and his colleagues during military training in Japan. (Photo: Public Domain) Suzuki’s relations with his own military headquarters were also in question. Some historical accounts suggest that there

- 7. was no higher-level interest in Aung San and his colleague Hla Myaing: Suzuki reported the arrival of the two Myanmar activists in Japan to General Staff but was initially told no support would be provided. Suzuki began to receive serious attention from the imperial headquarters when the British reopened the Burma Road to send supplies to China. Only then did a plan to liberate Myanmar begin in Tokyo. Aung San and other young nationalists—mostly Burmans— were secretly brought to Hainan Island to receive intensive military training in mid-1941, months before the Pacific War began with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 8 of that year. Those with Aung San included Bo Let Ya, Bo Set Kya, and Bo Ne Win, all in their 20s. They were among those later known as the “Thirty Comrades.” According to one of the Thirty Comrades, Kyaw Zaw—then 21, and later a leading army officer in 1950s—the training was harsh. At times, they thought of rebelling or joining Chinese communist insurgents hiding out on the island. In his memoirs, he mentioned that at one point, a Japanese officer brought out a Chinese prisoner of war on whom to practice bayonet training. The practice was later documented in Myanmar when Burmese independence fighters captured suspected criminals and collaborators with allied forces. Commander Thunderbolt The Burma Independence Army (BIA) was formed in December 1941 in Bangkok, before the Thirty Comrades’ return to Myanmar. Suzuki was the group’s commander in

- 8. chief, with the rank of General, and Aung San served below him as Chief of Staff. The BIA flag. (Photo: Public Domain) The Japanese promised that as soon as the forces crossed Myanmar’s eastern border and reached Moulmein (now Mawlamyine), independence would be announced. It was not.

- 9. Before entering Myanmar, the Thirty Comrades and Suzuki chose noms de guerre: Aung San became Bo Teza. Suzuki also chose a Burmese name: Bo Mogyo, or “Thunderbolt.” There was a reason behind it: a popular ta baung, or Burmese prophecy, widely shared among Myanmar people suggested that a thunderbolt would eventually strike down the umbrella, a symbol of British colonial rule. Suzuki not only identified himself as this savior, but also spoke of being a descendent of Prince Myingun, who was exiled from the Burmese royal family. Before they marched on Myanmar, the Thirty Comrades held a thwe thauk ceremony in a house in Bangkok, a tradition among soldiers in which a small amount of their blood was mixed with liquor and then consumed by the group. The initial BIA forces included Myanmar exiles and hundreds of Thai of Burmese origins. When the imperial headquarters asked Suzuki how he wanted assistance and arms for the BIA, Suzuki replied that he would need arms and equipment for 10,000 men but did not require any Japanese troops. According to Suzuki, when they entered Myanmar they had 2,300 men and 300 tons of equipment. Along with Japan’s 15th Army, they entered southern Myanmar and swiftly moved toward Moulmein. Suzuki and Aung San wanted to reach Yangon first—by March, the capital fell to Japanese forces. Speaking later to Dr. Maung Maung, Suzuki said that Aung San’s “patriotism and honesty won over all of us in Japan, as well as on our march.”

- 10. BIA troops enter Yangon in early 1942. (Photo: Public Domain) Before troops arrived in Yangon, Japanese planes bombed the city, forcing people to flee to the countryside. British and Indian populations—including soldiers, officers and civil servants—retreated west, to India. Shocking tales of a new “master” traveled fast to Yangon, including stories of Japanese solders’ abuses, including rape, torture, gruesome interrogations, lootings and extrajudicial killings. British and Indian troops destroyed strategic roads, bridges, and hospitals leaving little which could be of use to the enemy.

- 11. When the young Burmese nationalists’ aspirations of independence failed to materialize, they confronted Suzuki. He famously told then politician U Nu—who later became the Prime Minister—that one could not beg for independence, but rather, had to proclaim it. Suzuki allegedly suggested that the Burmese forces form their own government and revolt against Japan. Aung San reportedly replied to him that as long as Suzuki was in the country, he would not undertake such a move. In his own account to Maung Maung, Suzuki said he called in his own officers and asked they would follow him if he turned and fought the Japanese. It is unclear why Suzuki would have encouraged such action—whether he wanted the BIA to remain as his own army, away from the command of the Imperial Japanese forces, or whether he deeply romanticized the Myanmar nationalist struggle. Either way, it did not go down well with Japan. In 1942, Suzuki was called back to Tokyo and Aung San became war minister. The BIA—originally formed in Japan—was re-organized into the Burma Defense Army (BDA), of which Aung San was the head. Japan declared independence for Myanmar from the British, but the Burmese continued to struggle for freedom from foreign domination, this time by the Japanese. Massacre Under Japanese Occupation

- 12. Before departing Myanmar, Suzuki witnessed and was reportedly involved in volatile ethnic and racial conflict that remains a scar on the country today. When BIA troops marched across the Thai border, Burmans frequently welcomed them, but ethnic minorities remained apprehensive. Many groups had large numbers of recruits by the British, including the Karen, Karenni, Chin and Kachin. As the British retreated, promising to return, Karen soldiers went back to their homes. BIA troops then came to disarm them, and confrontation was inevitable. According to one account in Donald M. Seekins’ book, Suzuki ordered the BIA to destroy two large Karen villages, killing all the men, women and children with swords. It was an act of retribution, after one of his officers was killed in an attack by forces resistant to the Japanese. The same account was also described in Brig-Gen Kyaw Zaw’s memoirs, as he served under Col Suzuki when BIA and Minami Kikan officers ordered attacks on ethnic Karen villages in the Irrawaddy Delta. The incident, Seekins wrote, “ignited race war,” with massacres continuing “on both sides,” until the Japanese army could “rein in the hooligan element in the BIA,” In Myaungmya, South of Pathein in the Irrawaddy Delta, 400 Karen villages were destroyed and the death toll reached 1,800, according to Martin Smith, author of “Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity.” Members of the Thirty Comrades like Kyaw Zaw, as well as other independence era politicians, describe in their memoirs the crimes of this period, now remembered as the Myaungmya Massacres.

- 13. In some cases, BIA troops wanted to restore law and order as they saw fit. When they arrested suspected British collaborators, they simply put them on court martial and executed them in public, frequently with bayonets, as the Japanese had done. Just before Myanmar gained its independence, Aung San himself was accused by a political rival of carrying out the summary execution of a village headman in Mon State who was accused of aiding the British as BIA troops moved into Myanmar. In any case, the conflict was not confined to Karen State. In April 1942, Japanese troops advanced into Rakhine State and reached Maungdaw Township, near the border with what was then British India, and is now Bangladesh. As the British retreated to India, Rakhine became a front line. Local Arakanese Buddhists collaborated with the BIA and Japanese forces but the British recruited area Muslims to counter the Japanese. “Both armies, British and Japanese, exploited the frictions and animosity in the local population to further their own military aims,” wrote scholar Moshe Yegar, in his book “Between Integration and Secession: The Muslim Communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma/Myanmar.” Communal strife and retaliation ensued between the two communities as thousands were killed or died of starvation under Japanese occupation—Moshe Yegar estimates that as many as 20,000 people were lost regionally in the conflict. If

- 14. this happened today, it would undoubtedly demand international intervention. When countering Japanese and BIA forces, the Muslims of Arakan, wrote Moshe Yegar, played a valuable military role in reconnaissance missions, intelligence gathering, the rescue of downed aviators and raids on Japanese collaborators. This support arguably enabled the British to recapture Maungdaw and later, all of Rakhine. Soon after independence, the Arakanese began a struggle for an independent state of their own, and Muslims began the Mujahid movement to join East Pakistan (Bangladesh). Today, conflict and division in the region continue. When Aung San turned against Japan in 1945, the Karen, Kachin and Karenni and other minorities received arms and assistance from the British to fight against retreating Japanese forces. “Karen and Karenni guerrillas were later estimated to have killed more than 12,500 Japanese troops retreating through the eastern hills,” according to Martin Smith. The majority of offensives were carried out by allied forces and Gen William Slim, who led the 14th Army and the campaign that eventually defeated the Japanese. Lasting Friendship Suzuki’s protégé and former war minister Gen Aung San was assassinated in July 1947 at age 32. Seven years after they met in Tokyo, the young student activist had developed and

- 15. demonstrated the qualities of a statesman as he matured and gained a stronger understanding of the complexities facing his country.

- 17. Col Aung San and Daw Khin Kyi after their marriage in 1942. (Photo: Public Domain) Bo Let Ya, one of Aung San’s more favored colleagues and a leading member of the Thirty Comrades, became the deputy minister of War Affairs and also served as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defense under Prime Minister U Nu’s administration. He was jailed by Ne Win shortly after the coup in 1962. After serving his prison term, he fled to the Thai-Myanmar border to join resistance forces and fight against Gen Ne Win’s regime. Karen rebels in the jungle killed him in 1978. Bo Ne Win’s assignment in the BIA was to lead an advanced team into Myanmar to create disturbance and work behind enemy lines. In Hainan, he received training in sabotage and intelligence gathering; in 1962 he staged a coup and became head of the Revolutionary Council. Under his leadership, he built a much feared spy network throughout Myanmar. Gen Ne Win has been condemned as one of the most repressive dictators in Asia. He ran—and arguably ruined— the troubled country until 1988 when his government faced a massive uprising. Disgraced, he resigned and died quietly in 2002 while his grandsons served lengthy jail terms under the military regime he had handed power to in the political turmoil of 1988. Ne Win maintained close relations with Suzuki and Minami Kikan members until Suzuki passed away in 1967. Ne Win had invited him to Burma in 1966, one year earlier. In 1981, Ne Win bestowed the remaining six veterans of the Minami Kikan with honorary awards—the Aung San Tagun,

- 18. or the “Order of Aung San”— at the presidential palace in Yangon. Col Suzuki’s widow came to the ceremony. After his coup, Ne Win still needed Japan’s assistance. Myanmar received more than US$200 million from 1955 to 1965. In addition, Tokyo’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) served as a vital lifeline to the Ne Win regime and its successors. The country depended on Japan’s war reparations and ODA. Even after the 1988 massacre and bloody coup, Tokyo recognized the regime then known as the State Law and Order Restoration Council. Even after he resigned as Burma Socialist Programme Party chairman in 1988, Ne Win held gatherings of old Minami Kikan members into the mid-1990s. It is believed that the Minami Kikan remained in contact with Myanmar governments until 1995. In a 2014 trip to Japan, the Myanmar Army’s Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing visited the tomb of Col Suzuki to pay his respects. In the minds of many Myanmar Army officers, Suzuki remained a key figure: the man behind the clandestine beginnings of the BIA and the nucleus of the legendary Thirty Comrades. A controversial figure to both his own mission and his country’s top brass, Suzuki continues to be remembered as influential in Myanmar’s history—his and Japan’s direct involvement in Myanmar’s independence movement has had far reaching consequences. Members of the thakin movement were originally unarmed, but these young politicians and activists soon found a resourceful foreign ally who was ready to assist them in

- 19. liberating Myanmar. This no doubt changed the political dynamics in a country where some ethnic groups had once enjoyed relative autonomy and peace under British rule. Today, all of the legendary Thirty Comrades have died, and many of Myanmar’s problems and complexities remained unresolved. The irony was that liberation brought more chaos, rebellion, and division, and a state run by the army, not the nation’s people. Suzuki’s legacy lives on among the Burmese and the military generals, as does the notorious war machine and lingering conflict. Aung Zaw is the founding editor-in-chief of The Irrawaddy. Topics: Aung San, Foreign Relations, Heritage, Japan, Military, World War II Aung ZawThe IrrawaddyAung Zaw is the founder and Editor- in-Chief of The Irrawaddy. Colonel Keiji Suzuki, a Lawrence of Arabia figure, who encouraged Aung Sang and his thirty comrades to form a Burmese independence force

- 20. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 1/18 JPRI Working Paper No. 60: September 1999 Japan's "Burma Lovers" and the Military Regime by Donald M. Seekins Japanese people often claim that their nation has a "special relationship" with Burma. Most older Japanese think of Michio Takeyama's novel Biruma no tategoto (translated by Howard Hibbett as Harp of Burma), the story of Private Mizushima, a good-hearted soldier who is separated from his comrades and dons the robes of a Buddhist monk. When his unit is repatriated to Japan after the war, he refuses to go with them, staying behind to take care of the remains of the Japanese war-dead. As many as 190,000 Japanese soldiers died in Burma in 1941-1945, and groups of veterans regularly visit the country to relive old memories and pray at the graves of fallen comrades. The other side of the special relationship is Japan's assistance to young Burmese nationalists who opposed the British colonial regime. The most important nationalist leader, Aung San (father of pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi), fled the country with the colonial police hot on his trail in the summer of 1940, making contact with Japanese agents on the China coast. He was brought to Japan where he met Colonel Keiji Suzuki, a colorful, Lawrence-of- Arabia-type figure who had been involved in covert activities in Burma and set up the Minami Kikan, or Minami Agency, to organize local armed resistance against the British. The prewar Japanese military was interested in Burma because it needed the region's natural resources, especially oil, and wanted to cut the Burma Road through which Britain and the United States supplied the beleaguered Chiang Kai-shek government in Chongqing. Aung San soon returned to Burma and recruited other young nationalists who became the "Thirty Comrades," a pantheon of heroes who were given military training by the Minami Kikan on the Japanese-occupied island of Hainan. When war broke out in December 1941, the

- 21. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 2/18 Thirty Comrades became the nucleus of the Burma Independence Army (BIA), which fought alongside the Japanese army in its conquest of the country in early 1942. Most of modern Burma's leaders were associated in one way or another with the Japanese during the war. Aung San became war minister in the "independent" Burmese state proclaimed by Prime Minister Hideki Tojo in August 1943. U Nu, wartime foreign minister, became the country's first prime minister after the country achieved independence in 1948 (Aung San had been assassinated by a political rival in July 1947). Wartime commander of the army, Ne Win, who was also one of the Thirty Comrades, became the country's military dictator from 1962 until 1988. The most important legacy of the Japanese occupation was the establishment of a powerful national army, Tatmadaw in Burmese, which grew out of the BIA and was largely modeled on Japanese rather than British lines. Many of its officers studied at Japanese military academies during the war. Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt, a leading member of the military junta that has ruled Burma since September 1988, commented in November 1988, "We shall never forget the important role played by Japan in our struggle for national independence" and "We will remember that our Tatmadaw [army] was born in Japan."1 Ethnic minorities like the Karens and Shans who have experienced the Tatmadaw's counterinsurgency campaigns in the border areas claim that its brutal behavior was inspired by the Imperial Japanese Army. For Aung San and most of his colleagues, the wartime struggle was against colonialism. Disillusionment with the Japanese occupation set in quickly, however, and in 1944 they organized an underground Anti-Fascist Organization. On March 27, 1945, known today as Anti-Fascist Resistance Day, Aung San and his men rose up against the Japanese and joined forces with the Allies. Aung San was ready to use the assistance of any foreign nation to gain his ultimate goal of Burmese independence. Wartime ties between Burma and Japan were primarily a Burman phenomenon. (The term "Burman" refers to members of the ethnic majority, about two-thirds of the country's population. Burma has as many as one hundred and thirty-five different ethnic groups, the largest being the Shans, Karens, Kachins, Mons, Karenni, and Chins. I shall use the term "Burmese" to refer to citizens of Burma regardless of their ethnic ties. In 1989, the military regime changed the official foreign language name of the country from Burma to Myanmar. The ethnic majority are known as "Bamars," while the ethnically neutral name for all nationals

- 22. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 3/18 is Myanmarese or Myanmars. However, the name-change is highly controversial politically inside the country, and many writers outside the country continue to use the older terms Burma, Burman, and Burmese.) The British colonial army was made up primarily of ethnic minority soldiers, mostly Karens, Chins, and Kachins. These groups and other "hill tribes" living in the country's border areas remained mostly loyal to the British during 1941-1945, such as General Orde Wingate's famous Chindits in their operations behind Japanese lines. The Japanese-sponsored Burma Independence Army was the first predominantly Burman armed force since the British abolished the old monarchy in 1885. In 1942, ill-disciplined BIA men attacked Karen villages in the Irrawaddy delta, and hundreds were killed. This cost the Burman leadership the Karens' trust despite efforts by Aung San and Burma's wartime leader Dr. Ba Maw to promote ethnic harmony. After the country became independent in 1948, the Karen National Union (KNU), supported by some British unwilling to desert their wartime allies, started an insurrection which has continued for more than half a century. Although the major protagonists have long since quit the scene, this forgotten battle of World War II still rages today as the KNU fights the central government from its hard-pressed strongholds along the Thai-Burma border. Postwar Economic Ties Postwar relations between Japan and Burma were primarily economic in nature. Official ties began in 1954, after Tokyo and the U Nu government signed a peace treaty and a war reparations agreement, which brought the struggling young state some US$250 million in Japanese goods and services, supplemented by "quasi-reparations" amounting to US$132 million between 1965 and 1972. Tokyo allocated these additional "quasi-reparations" (jun baisho) on the grounds that the original funds were insufficient compared to those given other Asian countries. During this period, many Japanese who went to Burma as diplomats or technical advisers fell in love with the country. Back home, they were called biru-kichi (Biruma-kichigai, "crazy about Burma"), a remarkable attitude given the condescension with which most Japanese officials regarded their poor Asian neighbors. Japanese were impressed by the professionalism

- 23. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 4/18 and honesty of Burma's civil servants, who used reparation funds conscientiously, in contrast to some other recipient governments. Many Japanese also identified with the country because of shared Buddhist values, although the schools of Buddhism (Theravada in Burma, Mahayana in Japan) are different. Their social ethics are similar, however, stressing respect for elders and educated people, strong family ties, and a sense of mutual obligation. But while Japan had rapidly modernized and is losing many of these traditional values, Burma seemed to have preserved them uncorrupted by modernity. According to the well-known business guru Ken'ichi Ohmae, who visited Burma in 1997 with a Japanese business delegation and was a quick convert to the biru-kichi mindset, "Even I, with much contact with many Asian countries, have seen no other country in Asia whose morality is so firmly grounded in Buddhism."2 Ohmae compares Burma favorably with China where allegedly "they do everything for money." Burma also evokes his nostalgia for Japan's rural past: "Seeing the lives of the people in Myanmar [Burma], I remembered Japan in previous years. I was raised in the countryside in Kyushu, where children always walked around barefoot, the lights were not electric, and the bathrooms had no running water. The current Myanmar mirrors these memories of farming villages in Japan." While biru-kichi is a refreshing alternative to the insular Japan-is-unique worldview, it is not unmixed with other motives, as the title of Ohmae's November 26, 1997, article in Sapio (magazine) suggests: "Cheap and Hardworking Laborers: This country Will Be Asia's Best." After Ne Win seized power in a March 1962 coup d'état, putting an end to Burma's brief experiment with parliamentary government, he established a Soviet-style centralized economy under the rubric of the "Burmese Road to Socialism." Foreign- and domestically-owned enterprises, large and small, were nationalized and put under the control of inept military officers. Civil service professionals were purged. By the late 1960s, the economy was slouching toward disaster. In what had once been the world's largest exporter of rice, food shortages began to occur. During the early 1970s, a desperate Ne Win, beset by popular unrest, booted dogmatic socialists out of his junta and began making noises about economic liberalization. International lenders such as the World Bank and the Asia Development Bank, along with major donor countries such as Japan, West Germany, and the United States, began to listen. After the establishment of a Burma Aid Group of bilateral and multilateral donors which held its first

- 24. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 5/18 meeting in Tokyo in 1976, the Ne Win regime began to receive substantial amounts of official developmental assistance (ODA). Japan was by far the largest donor of this aid. According to statistics published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), between 1973 and 1988, Japan loaned or gave US$1.87 billion to Burma, more than two-thirds of all bilateral aid disbursements to the country. Aid included project loans, commodity loans, grant aid, technical assistance, and food aid. During the 1980- 1988 period, Burma was consistently ranked among the top ten among Tokyo's aid recipients, with single year disbursements reaching levels of US$244.1 million in 1986 and US$259 million in 1988. This does not include funds given by Tokyo to multilateral institutions like the Asia Development Bank some of which were also used to fund projects in the country.3 The generosity of these disbursements is remarkable since despite his pledges to the contrary, Ne Win continued to preside during the 1980s over an inefficient and corrupt socialist economy which had none of the dynamism of other Asian aid recipients. Personal networks in Japan, including veterans and biru-kichi types, may have played a role in this generosity. In January 1981, Burma's strongman awarded seven members of the old Minami Kikan with the Order of Aung San (Aung San Takun), the country's highest decoration, for their contributions to Burma's struggle for independence. But the bottom line rather than war memories explains Tokyo's large aid outlays. Four important factors were (1) Burma's reputation as a country rich in natural resources, especially oil and natural gas (Japanese companies carried out oil exploration in the 1970s); (2) future investment possibilities in a country with a low-wage and literate labor force; (3) the interests of major Japanese companies, especially general trading companies, which stood to benefit from aid contracts (by the late 1980s, eleven general trading companies had offices in Rangoon); and (4) Japan's practice of tying its aid to purchases by the recipient countries of expensive Japanese "hardware" rather than small-scale indigenous or human-capital projects, which makes these contracts especially profitable to Japanese exporters. Statistics published by the Japan International Cooperation Agency show that between 1978 and 1987, 28.2 percent of all Burma aid projects were in the mining, manufacturing, and energy sectors. 21.2 percent were public works projects, and 18.9 percent were in agriculture and fishing. Only 2.2 percent and 2.7 percent were in human resources and health respectively. As budgets for Japan's ODA rose steadily through the 1980s, Burma emerged as an ideal

- 25. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 6/18 location--from a business and administrative standpoint--for large, costly, and sometimes inappropriate projects. The quantity of Japanese ODA to Burma is perhaps best appreciated by comparing it with funds allocated to other Asian recipients during 1980-1988. Burma received the equivalent of US$1.42 billion, or 63 percent of the amount given to Thailand (US$2.24 billion), the newest of Asia's newly industrializing countries, and 42 percent of the amount given to Indonesia (US$3.36 billion), which has vied with China as Tokyo's top aid recipient. Most of these funds were in the form of concessional loans for the kinds of large projects mentioned above. One of the more unusual projects was a planetarium built near Rangoon's famous Shwe Dagon Pagoda which can be used to plot the conjunctions of the stars. According to journalist Bertil Lintner, Ne Win, who was obsessed with astrology, used the planetarium to plan his moves in an increasingly dangerous and unpredictable world (Aera, June 30, 1992). How did Burma benefit from the inflow of hundred of millions of dollars in loans and grants, mostly from Tokyo? Some inputs such as pesticides and fertilizers did contribute to significant growth of agricultural production after high-yield varieties of rice were introduced in the mid- 1970s, but rice yields stabilized and declined during the early 1980s for lack of further inputs such as farm mechanization. Aside from any astral guidance Ne Win might have gotten from his Japanese-built planetarium, foreign aid served as the regime's life-raft, keeping it afloat as the economy began to founder once again in the mid-1980s. The impact of aid on the people's standard of living was minimal. In 1987, the United Nations placed Burma in the status of "least developed country," with a per capita income of US$200 a year, one of the poorest in Asia. Although the Ne Win regime depended on foreign aid for transfusions of capital, especially from Japan, the Old Man (as Burmese commonly refer to him) was deeply xenophobic. Japan's policy of strictly separating political from economic policy (seikei bunri), its allocation of aid on the basis of requests from recipient governments (yosei-shugi), and its generally low profile in foreign relations made it a less threatening source of foreign capital than either of the superpowers or Burma's old colonial master Britain. Another major aid player was West Germany, the second most generous donor. A West German state-owned firm, Fritz Werner, built and operated small arms factories as a joint venture with the regime.

- 26. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 7/18 From Critical Distance to Limited Engagement In 1962 and 1974, student demonstrations broke out in Rangoon that were brutally suppressed by the authorities, causing hundreds of fatalities. However, no one was prepared for the countrywide pro-democracy movement of 1988, sparked when riot police killed university students in March and June. During "Democracy Summer," the demonstrations became a full scale revolution as townspeople, peasants, monks, and even military men joined student activists in demanding an end to Ne Win's dictatorship. Ne Win did resign his post as chairman of the Burma Socialist Program Party, the only legal political party, in late July, but he warned the populace that "in continuing to maintain control, I want the entire nation, the people, to know that if in the future there are mob disturbances, if the army shoots, it hits--there is no firing into the air to scare."4 Ne Win was a man of his word. After the students proclaimed a general strike on August 8, 1988, Tatmadaw troops fired point-blank on massed crowds of civilians in Rangoon and other towns, killing thousands. On September 18, 1988, generals loyal to Ne Win set up a martial law regime with the appropriately ugly acronym SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council). No one knows exactly how many people including women and children died during Democracy Summer, since the army carried away as many bodies as possible and cremated them with no attempt at identification. One credible estimate is one thousand dead in Rangoon alone after the SLORC putsch, which resembled the semaine sanglante (bloody week) of May 1872, when the French army stormed Paris and crushed the Paris Commune. Because much of the shooting took place in central Rangoon, it was witnessed by foreign diplomats. Among these was the Japanese ambassador, Hiroshi Ohtaka, who urged his government to freeze official developmental disbursements and delay formal recognition of the new military regime because of the political instability. On September 28, 1988, Ohtaka urged a "peaceful, democratic resolution of the crisis in accordance with the general wishes of the people." To his great credit, Ohtaka joined other Rangoon diplomats in boycotting SLORC's celebration of Burma's independence day on January 4, 1989, although he had attended the state funeral of Daw Khin Kyi, wife of independence leader Aung San and mother of Aung San Suu Kyi, two days before. From September 1988 to February 1989, Japan's response to the political crisis in Burma could be called "critical distance." It is unclear whether Ambassador Ohtaka's sympathies for the pro-

- 27. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 8/18 democracy movement were fully endorsed by foreign ministry officials in Tokyo. There is evidence, moreover, that Tokyo was also strongly pressured by the United States to freeze aid and hold SLORC at arm's length (based on a comment of a State Department official to the author, September 17, 1992). It took the Japanese government about five months to work up a consensus to move from "critical distance" to "limited engagement," reflected in the "normalization" of relations between Tokyo and SLORC announced on February 17, 1989. Unlike most countries, Japan has government-to-government rather than state-to-state diplomatic relations, meaning that if a new regime is established through extra-legal means such as a coup, Tokyo must make a conscious decision whether to grant it recognition. Before that time, Japanese diplomats cannot have any formal contacts with the new regime. Arousing considerable international criticism, normalization seems to have been a compromise worked out between Japan's three main government agencies concerned with aid policy. The Ministry of Finance had become uneasy about the huge amounts of official developmental assistance funds being poured into the black hole of Ne Win's socialist economy and the regime's inability to service its international debt (almost US$5 billion in 1988). The Ministry of International Trade and Industry represented business interests that had a big stake in the continuation of the aid gravy train and were also supportive of SLORC's decision to welcome foreign private investment. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs performed a delicate tightrope act, trying to preserve good relations with "the friendliest country in Asia toward Japan" while appeasing Japan's Western trading partners who condemned the junta and later imposed economic sanctions. Business interests were behind a petition presented to the Japanese government on January 25, 1989, by the Nihon-Biruma Kyokai (Japan-Burma Association, now known as the Nihon- Myanmaa Kyokai), a group whose members were an honor role of Japan's top trading, construction, and manufacturing firms (interestingly, its chairwoman was Ambassador Ohtaka's wife, Yoshiko Ohtaka, who was also a close friend of Ne Win). The petition called for the reopening of frozen aid on the grounds that huge losses would be sustained by firms with ODA contracts. It stressed the two countries' "historical friendship" and expressed concern that unless normalization took place, the Burmese government would not be able to send an official representative to the funeral of the Showa emperor in late February 1989. It also warned that if

- 28. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 9/18 Japan disengaged, Asian competitors like South Korea would take over this promising market.5 Foreign Ministry officials denied that the Nihon-Biruma Kyokai petition had any impact on the normalization decision. Aside from the fact that it viewed SLORC as exercising effective control over most of the country and observing international treaties, the Ministry believed that limited engagement would encourage the junta to make good on its September 18 promise to hold "multi-party democratic elections." New political parties had been allowed to organize days after the putsch in order to contest the election, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD). Just before normalization, an official of Burma's foreign ministry told a visiting Japanese delegation that election laws had been drafted and that the voting would be held by mid-1990. The election was held on schedule May 27, 1990, and the NLD won sixty percent of the vote and eighty-two percent of the seats in the People's Assembly. The regime simply refused to recognize the results. Because of her leadership of the democracy movement and refusal to back down in the face of military harassment, Suu Kyi was awarded the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize. The Japanese government considered normalization a plausible alternative to "business as usual"--the shovelling of more yen loans and grants into the official developmental assistance pipeline as was done during the Ne Win era--or extending diplomatic recognition without giving any ODA, old or new. The former would have damaged Japan's international image and created one more contentious issue between Tokyo and its Western trade partners, but the latter would have meant the end of Japanese influence in Burma, carefully built up over the previous thirty-five years. Such influence, Foreign Ministry officials explained, could be used to promote democratization. The Post-1988 Japanese Presence For business interests the bottom line of normalization was that some funds for ODA projects which had been approved before 1988 were now released, pending case-by-case approval by the Japanese government. No new aid was to be given, apart from humanitarian aid. Yet the Japanese aid presence in Burma after 1989 has not been insignificant. According to OECD statistics, an average sum of US$71.6 million was transferred annually during 1989-1993. Ironically, Burma once again achieved "top ten" status among Tokyo aid recipients in 1991. On top of this, the Japanese government gave debt relief grants totalling tens of billions of yen and

- 29. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 10/18 continued to provide technical advisers and accept Burmese trainees in Japan (for example, at the Japan International Cooperation Agency's lavish international center in Urasoe, Okinawa). The junta has sometimes used Japanese aid in questionable ways. According to the respected journal Jane's Intelligence Review (December 1998), debt relief grants have been diverted to procure items such as a "special combat vehicle" based on a Nissan truck, designed by the Tatmadaw for urban warfare. These trucks may be far from state-of-the-art weaponry, but they have proved indispensable in crushing public demonstrations, especially when equipped with machine guns. The special combat vehicle was first used to quell renewed student demonstrations in December 1996. Japanese law forbids the military use of aid funds, but Burma's generals are intent on building up the largest armed force in Southeast Asia. What was defined as "new aid" and "old aid" became frustratingly ambiguous. For example, in February 1998, in a move which both Aung San Suu Kyi and the U.S. government severely criticized, the Japanese government announced the release of ¥2.5 billion (a little under US$20 million) in loan funds for renovating Rangoon's Mingaladon International Airport. This was part of a ¥27 billion airport modernization project which received no new funds after 1988 for technical as well as political reasons. Some Tokyo officials described this newly released aid as "humanitarian aid," designed to prevent air crashes, since All Nippon Airways operates a regular service between Kansai Airport and Mingaladon. Other Japanese officials justified the airport loan as a "carrot" to encourage the regime to go easy on the political opposition. They expressed satisfaction that after it was announced the junta (which dropped the SLORC acronym and adopted the softer-sounding name State Peace and Development Council or SPDC in November 1997) allowed the National League for Democracy to hold a congress in May 1998, the eighth anniversary of its victory in the 1990 general election. But after May, the SPDC once again stepped up its evisceration of the NLD, detaining party members, closing down branch offices, and severely restricting Suu Kyi's movements, all of which suggested that the Japanese government's "sun diplomacy" --giving monetary rewards for democratization gestures--was not very effective. Some observers believe the Japanese government played an important behind-the-scenes role in the junta's decision to release Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest in July 1995. Soon after, Tokyo announced a grant of ¥1.6 billion to renovate a Rangoon nursing college as a reward for its good behavior. But again there was no real progress toward democratization.

- 30. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 11/18 While the Mingaladon Airport funds caused an uproar in Japan, a number of small-scale projects, also under the rubric of humanitarian or grass-roots aid, have gone largely unnoticed by the public. One of the most interesting came to light when former Liberal Democratic Party Secretary General Koichi Kato visited Burma in late February 1999. Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt took Kato to Kokang, a remote district on the northeastern border between Burma and China which is a major center of opium production. Kato, chairman of the "Japan Buckwheat Association," became an eager convert to the biru- kichi mentality a couple of years ago, and was supposedly inspecting a crop-substitution project funded by the Japanese government and the LDP. Its purpose is to encourage Kokang's desperately poor farmers to grow buckwheat rather than poppies. The crop would then be exported to Japan to make soba noodles.6 The Kokang area in what is known as the Golden Triangle is controlled by a drug-dealing warlord gang known as the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) which signed a cease-fire with the SLORC junta in 1989. Lt. Gen. Khin Nyunt negotiated the cease- fire deal with the MNDAA and is today in charge of the junta's "border development" policies. It is difficult to assess the project's effectiveness. Crop-substitution programs have succeeded in neighboring Thailand where hill tribes once grew poppies, but they depend on the availability of markets for the new crops. Khin Nyunt has also been a zealous builder of international ties, especially with China, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), and Japan. In 1994, he established a "think tank," the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS), manned by military intelligence officers with overseas experience and containing an international affairs department. Its responsibilities include establishing contacts with foreign opinion-leaders, hiring Washington public relations firms to refurbish Burma's image in the West, and establishing on-line information services to battle anti-regime dissidents in cyberspace. That the Japanese government recognizes this new OSS as an emerging center of political power is reflected in the Foreign Ministry's invitation to its current director, Brigadier General Kyaw Win, to visit Japan. During his low-profile visit with three other OSS officers in January 1999, he met with a wide range of public and private figures. The Foreign Ministry explained the controversial decision to bring them to Tokyo as part of its on-going policy of "quiet dialogue," urging the junta to democratize. During meetings with Japanese officials Kyaw Win

- 31. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 12/18 explained that the junta would transfer power to a democratically elected government after a constitution had been drafted and a general election held (in other words, the junta would continue to ignore the NLD victory in the May 1990 election). The ten-day visit was cut short for unexplained reasons. One diplomat in Rangoon suggested to this writer it was because of anti-junta demonstrations by Burmese exiles and their Japanese supporters. Given the OSS's central role in the junta's and General Khin Nyunt's emerging power structure, critics in Japan could not be faulted for thinking the Foreign Ministry had pursued "limited engagement" a bit too far. Aside from his international activities, Khin Nyunt is chief of Burma's military intelligence. He is called "the prince of darkness" by oppositionists and has been directly responsible for some of the regime's worst human rights violations, including the routine torture of political prisoners. Japanese Business and the So-called Suu Kyi Problem While the Japanese Foreign Ministry claims to be engaged in a "quiet dialogue" with the junta to promote democratization, business interests have turned a blind eye to politics and lobbied for full economic engagement, including new aid. As early as June 1994, Keidanren, the powerful Federation of Economic Organizations, sent a special fifty-man mission headed by Marubeni chairman Kazuo Haruna to Rangoon to meet with the junta's top brass. In the wake of the mission, many Japanese companies, especially banks, opened branch offices in Rangoon. Two years later, in May 1996, Keidanren upgraded its informal study group in Burma to a "Japan-Myanmar Economic Committee." The timing was less than opportune, for SLORC was then in the middle of a crackdown on the NLD about which the Japanese government expressed great concern. Business interests also seem to have been behind the June 1998 formation of a group of Diet members, the "Parliamentarians' League to Support the Myanmar Government," led by Kabun Muto, a powerful member of the LDP. According to 1998 statistics, Japan is only the ninth largest foreign investor in Burma, after Singapore, France, Britain, and even the United States. Japan has US$219 million in private funds committed to Burma, or 3.1 percent of total foreign private investment. This suggests that mainstream companies consider the business environment excessively risky outside the profitable channel of official developmental assistance contracts. Yet practically all major trading companies continue to have representative offices in Rangoon, preparing for the day

- 32. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 13/18 when conditions are ripe for a return to the pre-1988 relationship. The Japanese construction and manufacturing sectors are also well-represented. Aside from ODA self-restraint, Japanese businesses wanting to expand their operations in Burma have another problem: Aung San Suu Kyi. As pro-democracy leader, she has opposed any form of economic engagement (except for carefully monitored humanitarian aid), and in one of her "Letters from Burma" published in the Mainichi Shimbun and Mainichi Daily News, she singled out Japan for special criticism: To observe businessmen who come to Burma with the intention of enriching themselves is somewhat like watching passersby in an orchard roughly stripping off blossoms for their fragile beauty, blind to the ugliness of despoiled branches, oblivious of the fact that by their actions they are imperilling future fruitfulness and committing an injustice against the rightful owners of the trees. Among these despoilers are big Japanese companies.7 In the same letter, she mentions "forced labor projects where men, women, and children toil away without financial compensation under hard taskmasters reminiscent of the infamous [Japanese-built] railway of death of the Second World War." For a country wrestling with its wartime aggression in Asia, she chose potent imagery. On the other hand, her letter concludes, "At the weekend public meetings that take place outside my gate, there are usually a number of Japanese sitting in the broiling sun, who, although they cannot understand Burmese, pay close and courteous attention to all that is going on. And . . . at the end of the meeting, many of them come up to me and say Gambatte kudasai! [Don't give up]." Many inside Japan's business world--and their supporters in academia and the media--seem to share a common goal with the junta: discrediting Aung San's daughter. Given her central role in the struggle for democracy, it is not an exaggeration to say that if she could be marginalized and lost the support of the international community, big corporations in Japan and elsewhere would find it easy to get their governments to snuggle closer to the junta. Without Suu Kyi, full economic engagement and recognition would surely follow swiftly. Kazushige Kaneko, director of an obscure Institute of Asian Ethnoforms and Culture in Tokyo, repeats the junta's racist charges that Aung San Suu Kyi sold out her country by marrying a foreigner, the late Oxford professor Dr. Michael Aris. He writes, "For example, if Makiko Tanaka [the daughter of former Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka and today a member of the

- 33. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 14/18 Diet] stayed in America for thirty years and returned with a blue-eyed American husband and children, do you think we Japanese would make her our prime minister?" (The Asia 21 Magazine, Fall 1996). Nor is the attack on Aung San Suu Kyi confined to fringe figures. In an April 1995 article published in Bungei Shunju, Yusuke Fukada claims that Burmese are sending out a "love call" (rabu kooru) to Japan for economic assistance and that Suu Kyi is the only real obstacle to better relations. The reason she is so uncompromising with the military regime, Fukada argues, is her marriage to an Englishman. "If she had married a Japanese, she would have made quite different decisions." In the June 1996 issue of Shokun, Keio University Professor Atsushi Kusano expresses amazement that Suu Kyi has become a figure of international stature, attributing it to a campaign by the mass media.8 Ken'ichi Ohmae's Views on Suu Kyi Ken'ichi Ohmae, popular author of business-oriented books such as World Without Borders, is undoubtedly Japan's biggest gun when it comes to promoting the Burma connection. In his November 1997 articles in Sapio, he extolled the country's economic potential: its honest, hard-working people, its rich natural resources, and above all its low-wage labor force. In fact, he is impressed with the cheapness of just about everything Burmese: "In the hotels, a haircut cost $15, a massage cost $10, and children in the streets charged $1 for twenty postcards. . . . One friend of mine bought a ruby initially priced at $200 but after the negotiation it was $5" (Sapio, November 26, 1997). A student of cultural studies would find his comments a textbook example of "Orientalism," since he envisions a colonial-type situation in which Burma's happy workers and peasants, living in a premodern Garden of Eden, enrich a foreign (i.e., Japanese) business elite. Substitute the Irrawaddy Flotilla and Steel Brothers (colonial-era British firms) for Mitsui and Marubeni and one would think that Ohmae was the chairman of the Rangoon Chamber of Commerce talking to fellow businessmen in 1900. Two serpents in this Garden of Eden are the United States, which has imposed economic sanctions on Burma and would like other countries to do the same, and Aung San Suu Kyi, who--Ohmae claims--Washington regards as "the Jeanne d'Arc of Myanmar":

- 34. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 15/18 The U.S. . . . is using her to spread their propaganda and pressure the regime. However, why the U.S. feels the need to do this and to achieve what end is beyond my comprehension. . . . One cannot help but think that in a year or two, Mrs. Suu Kyi will be a person of the past. Although the government is a military authority, it has relaxed regulations and implemented liberalization measures aiming for a market economy. This year, after finally realizing Burma's admission into ASEAN, as in the fable of "North Wind and the Sun," Myanmar has started to shed its coat. In regard to infrastructure, significant improvements have been made. . . . Despite the general aversion to the military authority, such visible progress allows people to accept its accomplishments and to say that time will leave Suu Kyi behind (Sapio, November 12, 1997). In a special year-end issue of Asiaweek (December 1997), Ohmae disparaged Suu Kyi's 1990 election victory, again linking her to the United States: "The West knows Myanmar through one person, Aung San Suu Kyi. The obsession with Suu Kyi is a natural one if you understand the United States. Superficial democracy is golden in the U.S.: Americans love elections. Just as Myanmar is Buddhist, and Malaysia is Islamic, America has a religion called democracy." It is no coincidence that Ohmae has been close to Malaysia's Prime Minister Mohammad Mahathir, who is not only a promoter of the "Asian authoritarian model" (economic development first, democratization maybe later) but who has also been one of SLORC/SPDC's most vocal backers in Southeast Asia and sponsored its July 1997 entry into the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. In 1994, Mahathir and Ohmae jointly published a series of dialogues on Asia's enrichment and the role of allegedly distinct Asian values in it, entitled Ajiajin to Nihonjin (Asians and Japanese) with the English subtitle Japan in Asia's New Map (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1994). Revolutionary Nationalism The Asian authoritarian model as espoused by Ohmae and Mahathir will not, however, work in Burma. Not only are there the bloody events of 1988; the country's identity is also defined by revolutionary nationalism, first embodied in Aung San and now his daughter. The pro- democracy movement of 1988 was in many ways an uncanny reenactment of the countrywide strikes and demonstrations of 1938 against the British, except that the British colonial police claimed only twenty or so victims, whereas the Tatmadaw has claimed thousands. Aung San Suu Kyi's statement that the 1988 movement was Burma's "second struggle for independence" resonates deeply with a population oppressed by decades of inept military rule.

- 35. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 16/18 Indeed, Burma's revolutionary roots go back further than the colonial period. A theme which recurs often in the history of old Burma is the overthrow of an unjust ruler by a minlaung, a claimant to the throne, who governs benevolently according to Buddhist precepts. Many Burmese see Aung San Suu Kyi as a minlaung not only because of her "royal" blood (being the daughter of Aung San) but because of her courage and spiritual strength. (It should be pointed out that she has never expressed a desire to become Burma's leader.) Ohmae's attempt to belittle Suu Kyi as a made-in-America Jeanne d'Arc reveals his ignorance of Burmese revolutionary tradition. In denigrating Aung San's daughter, Ohmae, Kusano, and other representatives of Japanese business interests not only mimic the junta's own propaganda but run against deep currents of Burmese history. Two factors seem to account for Japan's ambiguous Burma policy. One is the strength of its business interests, counterbalanced by pressure from Japan's Western trading partners who take a less indulgent stance toward the junta. Some observers cynically suggest that Western governments, especially Washington, act as Tokyo's "superego" on human rights, inhibiting it from pursuing its usual economics-first policies. But Liberal Democratic Party cabinets cannot ignore business interests, which have been stepping up pressure for full engagement since 1989, using means both fair and foul. The best of both worlds for policymakers in Japan would be a transition to civilian rule, either involving Aung San Suu Kyi or someone else. This could legitimize more active aid policies as well as greater investment by Japanese companies. But given the political situation, this is unlikely to happen soon. Second, if Tokyo strongly supported the democracy movement in Burma, this would inevitably reflect on its policies toward other countries such as China and Indonesia, where the stakes for Japan are much higher. Some Americans have criticized their own government's inconsistency on this matter: the Clinton Administration maintains sanctions on little-known Burma but maintains full economic engagement with the regime in Beijing. Japanese elites are not used to and do not like open debate, especially on foreign policy. Some members of the Diet are interested in Burma, both pro- and anti-junta, but the issues are rarely discussed, even the junta's misuse of debt relief funds for the procurement of weapons. Bureaucrats and LDP bigwigs keep policy initiatives to themselves, which means that their actions often appear incomprehensible or arbitrary to outsiders, including Japanese citizens. The flap over so-called humanitarian aid for Rangoon's airport is an example of this. In a way, Tokyo's Burma policy, deeply influenced by the sentimental Orientalism of the business world

- 36. 8/27/2017 JPRI Working Paper No. 60 http://www.jpri.org/publications/workingpapers/wp60.html 17/18 and its allies, says as much about the limitations of Japanese-style democracy as it does about the lack of democracy in Burma. NOTES 1. Gustaaf Houtman, Mental Culture in Burmese Crisis Politics: Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 1999), p. 153. 2. This and succeeding Ohmae quotations are from Ken'ichi Ohmae, "Mrs. Suu Kyi Is Becoming a Burden for Developing Myanmar," Sapio , November 12, 1997; and "Cheap and Hardworking Laborers: This Country Will Be Asia's Best," Sapio, November 26, 1997 (translations supplied by the Burmese Relief Center, Japan). 3. Donald M. Seekins, "Japan's Aid Relations with Military Regimes in Burma, 1962-1991," Asian Survey 32:3 (March 1992): pp. 246-262. Also see Seekins, "The North Wind and the Sun: Japan's Response to the Political Crisis in Burma, 1988-1998," Journal of Burma Studies, forthcoming; and "Burma in 1998: Little to Celebrate," Asian Survey 39:1 (January-February 1999), pp. 12-19. 4. Bertil Lintner, Outrage: Burma's Struggle for Democracy (Hong Kong: Review Publications, 1989), p. 119. 5. Teruko Saito, "Japan's Inconsistent Approach to Burma," Japan Quarterly 39:1 (January- March 1992), pp. 17-27. 6. "'Keshi hatake o soba hatake ni,' mizukara teisho no jigyo shisatsu Myanmaa de Kato-shi" (From Poppy Fields to Soba Fields: Mr. Kato Inspects a Project He Promotes), Yomiuri Shimbun, March 1, 1999. 7. Aung San Suu Kyi, "Letter from Burma No. 22," Mainichi Daily News, April 22, 1996. For the full set of letters, see Aung San Suu Kyi, Letters from Burma (London: Penguin Books, 1997). 8. These and other writers are discussed by Nagai Hiroshi, "Yuganda media no naka no Biruma" (Burma in the Distorted Media), Sekai, August 1997, pp. 300-302. Nagai invented the term "Suu Kyi-bashing" to describe these writers' reports. DONALD M. SEEKINS is professor of Southeast Asian studies at Meio University in Nago, Okinawa, and author of "Sayonara Suu Kyi-san?" Burma Debate 5:1 (Winter 1998) and other articles on Burmese politics.

- 37. 8/27/2017 Burmanet » The Irrawaddy: Tokyo Calling http://www.burmanet.org/news/2014/09/30/the-irrawaddy-tokyo-calling/ 1/12 Home | FAQ | Links | Subscribe | Archives The Irrawaddy: Tokyo Calling Tue 30 Sep 2014 Filed under: News,Regional Last week, Burma Army Commander-in-Chief Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing paid his first official visit to Japan at the invitation of General Shigeru Iwasaki, Chief of Staff of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. This marked the first visit by a commander-in-chief to Tokyo since Gen Ne Win visited Japan in the 1960s. The recent visit will be seen as part of the Burmese armed forces’ outreach to allies—new and old— after the political opening in the country. Under Ne Win’s socialist government, Japan was Burma’s largest donor but scaled down its assistance and aid programs after the US and other Western nations imposed sanctions on the regime following the crackdown on the 1988 democracy uprising. But after recent reforms in Burma, Tokyo has not missed the chance to renew its old friendship, including by boosting defense ties between the two nations.

- 38. 8/27/2017 Burmanet » The Irrawaddy: Tokyo Calling http://www.burmanet.org/news/2014/09/30/the-irrawaddy-tokyo-calling/ 2/12 In May, Japan’s military chief, Gen. Shigeru Iwasaki, met with President Thein Sein in Naypyidaw where the two officials reaffirmed their countries’ goals of enhancing defense cooperation and exchanges at all levels. During his four-day visit, the Japanese general also met with Snr-Gen Min Aung Hlaing, holding discussions on security issues in the Asia-Pacific region, including Japan’s sovereignty row with China over the disputed Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, as well as territorial disputes in the South China Sea, where China has been aggressively asserting its claims. The Japanese Defense Ministry released a statement at the time saying that the two generals discussed bilateral defense cooperation and agreed on “the importance of exchanges at every level between the Self- Defense Forces and Myanmar Armed Forces.” During his recent trip, Min Aung Hlaing also paid a visit to the tomb of the late wartime Japanese officer Col Suzuki Keiji and his old residence. Col. Suzuki, who ran a special operations directorate known as Minami Kikan, played a key role in British- ruled Burma during the early stages of World War II when late independence hero Gen Aung San, then a young nationalist fugitive, sought overseas military assistance to liberate the country. When he was in Amoy, now known as Xiamen, in southern China, Japanese intelligence officers intercepted Aung San. There, the young nationalist leader met Col Suzuki who convinced him to receive military assistance from the Japanese for an uprising in Burma. Col Suzuki, whose Burmese name was Bo Mogyo (Thunder), had earned the respect and trust of Burmese nationalists.

- 39. 8/27/2017 Burmanet » The Irrawaddy: Tokyo Calling http://www.burmanet.org/news/2014/09/30/the-irrawaddy-tokyo-calling/ 3/12 Aung San subsequently brought a group of young men known as the legendary “Thirty Comrades” to be trained by Japanese officers in 1941. This was the beginning of the Burma Independence Army or BIA. The Kempeitai (the Japanese army’s military police) and other sections of Japan’s security forces also trained Ne Win, one of the “Thirty Comrades” who became chairman of the now defunct Burma Socialist Programme Party. Many officers who were trained by Japanese forces in the early 1940s also served as ministers in the Ne Win government. Ne Win maintained close relations with Suzuki and Minami Kikan members until Suzuki passed away in 1967. In 1981, Ne Win bestowed the remaining six veterans of Minami Kikan with honorary awards—the Aung San Tagun or ‘Order of Aung San’—at the presidential palace in Rangoon. Colonel Suzuki’s widow showed up for the ceremony. Even after he resigned as party chairman in 1988, Ne Win held gatherings of old Minami Kikan members as late as the mid-1990s. Japanese forces invaded Burma from Thailand to liberate the country from the British in 1942. Burma was then under Japanese occupation, headed by a puppet government. Aung San then formed an anti-fascist organization and joined with British and allied forces to drive out the Japanese in 1945. During the war, Japan lost 190,000 soldiers in Burma. Thus, it is safe to say that Burma holds a special place in many Japanese hearts. With the recent opening in Burma, it is also part of Burma’s strategic interests to balance against its powerful neighbor, China. Naypyidaw hasn’t wasted any time patching up, or initiating, relations with former or prospective allies. Since assuming the position of commander-in-chief of the armed forces, Min Aung

- 40. 8/27/2017 Burmanet » The Irrawaddy: Tokyo Calling http://www.burmanet.org/news/2014/09/30/the-irrawaddy-tokyo-calling/ 4/12 Hlaing has visited several countries in the region including the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, and Thailand (twice), and is currently visiting South Korea. Last year saw significant developments in Japan-Burma relations. In May 2013, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited Burma, the first visit by a Japanese PM since 1977. During the visit, Abe wrote off nearly US$2 billion in debt and pledged up to US$498.5 million in new loans. Thein Sein then travelled to Japan in December. Training vessels from Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force also made a first ever port call to Burma, for a five-day mission, in September. http://www.irrawaddy.org/burma/news-analysis/tokyo-calling.html Share this: Search Related Irrawaddy: Burma, China consolidating military relations - Min Lwin Irrawaddy: Selection time precedes election time in Burma – Aung Zaw Irrawaddy: A dictator's balancing act - Aung Zaw October 29, 2008 In "News" November 24, 2009 In "Opinion" February 23, 2007 In "News"

- 44. 8/27/2017 28 Dec 1941 | World War II Database https://ww2db.com/event/today/12/28/1941 1/4 Home » Events » WW2 Timeline » 28 Dec 1941 28 Dec 1941 I-68 arrived at Kwajalein, Marshall Islands and received temporary repairs. ww2dbase [Main Article | Tabular Record of Movement | CPC] American destroyer USS Peary, while in transit from the Philippine Islands toward Australia, was attacked by 4 Japanese aircraft at 1420 hours, causing no damage. At 1800 hours, she was mistaken for a Japanese ship and was bombed and damaged by 3 RAAF Hudson bombers off Kina, Celebes, Dutch East Indies, killing 1 and wounding 2. ww2dbase [CPC] The US Navy Chief of Bureau of Yards and Docks, Rear Admiral Ben Moreell, requested that construction battalions be recruited. These construction personnel were soon to be known as the "Seabees". ww2dbase [CPC] Lieutenant-General Thomas Hutton assumed command of Burma army. A competent and efficient Staff Officer (he had been responsible for the great expansion of the Indian army), he had not actually commanded troops for twenty years. Across the border in Thailand, Japanese Colonel Keiji Suzuki announced the disbandment of the Minami Kikan (Burmese armed pro-Japanese nationalists) organization, which would be replaced by the formation of a Burma Independence Army (BIA), to accompany the Invasion force. ww2dbase [Main Article | AC] Indian 22nd Brigade arrived at Kuantan, Malaya. ww2dbase [Main Article | CPC] German submarine U-75 attacked Allied convoy ME-8 off Mersa Matruh, Egypt, sinking British ship Volo; 24 were killed, 14 survived. British destroyer HMS Kipling counterattacked and sank U-75 with depth charges; 14 were killed, 30 survived. ww2dbase [CPC] Australia George Brett arrived in Darwin, Australia. ww2dbase [Main Article | CPC] Greece While in Athens, Greece, Hans-Joachim Marseille received a short telegram from his mother stating that his sister, Ingeborg, was dead, asking him to return to Berlin, Germany. ww2dbase [Main Article | CPC] Search WW2DB & Partner Sites Custom SearchSearch News » Wreck of USS Indianapolis Found (19 Aug 2017) » Unexploded WW2 Bomb Found Near Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant (11 Aug 2017) » New website Russian Retrospective (10 Jan 2017) » See all news Random Photograph Earl Louis Mountbatten at the terrace of his home, Belgravia, London, England, United Kingdom, 1976 World War II Database Home Intro People Events Equipment Places Books Photos Videos Others Reference FAQ About

- 45. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 4/16 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II

- 46. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 5/16 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II Monday, June 19, 2017 Mail A timeline of the Japanese invasion, British defeat, Allied reoccupation and political turmoil that would set the stage for an independent Burma. By JARED DOWNING | FRONTIER July 7, 1937: Japan invades China Under the command of Kuomintang Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, the Chinese Nationalists begin work in 1937 on the 1,154- kilometre (717-mile) Burma Road, connecting Kunming in Yunnan with Lashio, and ultimately Rangoon, to help supply their beleaguered forces in China. The Burma Road – along with Burma’s rubber, oil and other resources, and the country’s proximity to British India – make the country instrumental to Japan’s plans to dominate Asia. August 14, 1940: Aung San flees Burma as a political fugitive Aung San, then a 25-year-old activist, would soon be recruited by the Japanese to nurture an anti-colonial movement in Burma along with a hand-picked team that would be known as the “Thirty Comrades”. December 8, 1941: The last days of peace Facebook Twitter Facebook Messenger WhatsApp Viber LinkedIn

- 47. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 6/16 Japan forces Thailand into an armistice and immediately attacks British Malaya, the Philippines and Hong Kong. Already embroiled in a war in Europe, Britain declares war on the Empire of Japan. Burma was only defended by two divisions – the 17th Indian Division and the 1st Burma Division – but at the time the Allies, underestimating Burma’s strategic value and overestimating its jungles, mountains and rivers as natural defences, did not expect an invasion by the Imperial Japanese Army. December 14, 1941: The Japanese invasion Japanese forces begin the invasion of Burma by capturing a British airfield at Victoria Point (Kawthaung) at the country’s southern tip, cutting off British reinforcements bound for Malaya. The Allied Commander-in-Chief, India, General Archibald Wavell, (who had previously fought the Germans in North Africa) scrambles to rally Burmese forces for a counterattack with assistance from the Chinese Nationalists, but it is too late.

- 48. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 7/16 Illustration by Jared Downing | Frontier December 23, 1941: Bombing of Rangoon

- 49. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 8/16 Fighter planes from the British Royal Air Force and the 1st American Volunteer Group (the “Flying Tigers”) fight valiantly, but continued attacks over the coming months will devastate the city. February 19, 1942: First Japanese bombs fall on Mandalay February 22, 1942: The battle of Sittaung Bridge Retreating ahead of a smaller but more experience Japanese force, the 17th India Division – comprising British, Indian and Burmese troops – makes a stand at the bridge over the Sittaung River (about 140 kilometres by road northeast of Rangoon). The Battle of the Sittaung Bridge is a disaster. Allied forces destroy the bridge to slow the Japanese advance, inadvertently trapping two Indian brigades on the eastern side of the river. The Japanese find another way to cross the river and continue their rapid advance on Rangoon. March 9, 1942: Japanese enter Rangoon After days of bitter fighting at Pegu (Bago) and Taukkyan, British forces secure a retreat towards Mandalay. The Japanese Imperial Army enters an undefended Rangoon. As Chinese Nationalist forces head for Yunnan, retreating British and Indian troops, together with thousands of British and Indian civilians, endure a grim journey towards the safety of northeastern India. Thousands of civilians perish from hunger and disease during the exodus through mountains and jungles to the Indian border. May 1, 1942: Aung San and the Thirty Comrades return As the Japanese plotted their invasion of Southeast Asia, they had been nurturing an anti-British network in Rangoon and giving General Aung San and the other members of the Thirty Comrades military training on Hainan Island, then occupied by the Japanese. Most of the Thirty Comrades, the nucleus of the Burma Independence Army, had returned with invading Japanese forces through southern Burma in 1941.

- 50. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 9/16 In the coming months, under the guidance of Japan’s Colonel Keiji Suzuki (who called himself Bo Mogyo, or “Thunderbolt”), the BIA’s efforts to recruit volunteers were aided by the nationalist sentiment it aroused. The BIA would grow to about 18,000 soldiers, although many were untrained and underequipped and there were problems with maintaining discipline. The BIA (which would be refined and re-branded the Burma Defence Army, a forerunner of the Tatmadaw) saw some action but left the heaviest fighting to the Japanese. However, tensions grew between the Bamar and ethnic minority groups that had been loyal to the British, including the large Karen population in the Irrawaddy Delta. Mutual suspicion ended in violence and atrocities on both sides and the suppression of the Karen planted the seeds for what would become a 70-year civil war. May 20, 1942: Japanese complete conquest of Burma August 1, 1943: Japan grants “independence” to Burma The Japanese establish a provisional Burmese government with pre-war nationalist leader Dr Ba Maw as its head and Aung San as Minister of War. The Burma Defence Army is re-named the Burma National Army. Ba Maw’s government was fond of pomp and showboating, but the Japanese clearly held power. Life under the Japanese was as often brutal, with constant arrests, interrogations, executions, looting, sex slavery and forced labour. Burmese were among the 180,000 Asian forced labourers and 60,000 Allied prisoners-of-war who toiled on the infamous Death Railway, built by the Japanese to link Kanchanaburi in Thailand with Thanbyuzayat, about 60 kilometres south of Moulmein. The barbaric conditions under which they were forced to work claimed the lives of about 90,000 Asians and 12,400 Allied POWs.

- 51. 8/27/2017 Myanmar 101: Burma in World War II | Frontier Myanmar https://frontiermyanmar.net/en/myanmar-101-burma-in-world-war-ii 10/16 WikiCommons