Outline Before you start writing the first draft of y.docx

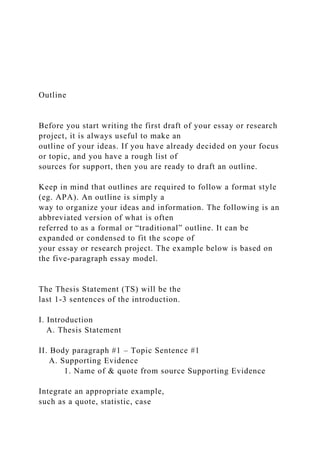

- 1. Outline Before you start writing the first draft of your essay or research project, it is always useful to make an outline of your ideas. If you have already decided on your focus or topic, and you have a rough list of sources for support, then you are ready to draft an outline. Keep in mind that outlines are required to follow a format style (eg. APA). An outline is simply a way to organize your ideas and information. The following is an abbreviated version of what is often referred to as a formal or “traditional” outline. It can be expanded or condensed to fit the scope of your essay or research project. The example below is based on the five-paragraph essay model. The Thesis Statement (TS) will be the last 1-3 sentences of the introduction. I. Introduction A. Thesis Statement II. Body paragraph #1 – Topic Sentence #1 A. Supporting Evidence 1. Name of & quote from source Supporting Evidence Integrate an appropriate example, such as a quote, statistic, case

- 2. study, etc. 2. Name of & quote from source #2 (if applicable) B. Explanation 1. Explanation of source 2. Explanation of source #2 (if applicable) C. So What? Explanation Explain how this evidence supports your topic sentence. Try to develop your explanation in 2-4 sentences. III. Body paragraph #2 – Topic Sentence #2 A. Supporting Evidence 1. So What? What’s significant or important about the ideas (topic sentence + evidence + explanation) in this paragraph? Remind your reader how all this connects back to the TS. 2. B. Explanation 1. 2. C. So What? IV. Body paragraph #3 – Topic Sentence #3 A. Supporting Evidence

- 3. The TS is the first 1-3 sentences of the conclusion. It should be “rephrased” here rather than repeated verbatim. Avoid simply summarizing the main points in the conclusion: synthesize them. B. Explanation C. So What? V. Conclusion A. Rephrase thesis statement B. Bring closure by going from specific to broad To see what a complete outline, refer to the model below. The thesis statement has been taken from the Thesis Statement Guide section of the Ashford Writing Center. I. Introduction A. Thesis Statement Although there are educational television programs, parents should regulate the amount of television their children watch because it is not always intellectually stimulating, it can distort a child’s perception of reality, and it inhibits social interaction. II. Body paragraph #1 - Topic Sentence #1 While television has the potential to offer programs that can

- 4. be seen as educational supplements, too much television has an even greater potential for turning children into passive viewers and getting in the way of intellectual stimulation. A. Supporting Evidence As a recent article from the University of Michigan Health Systems (2008) maintains, “Too much television can negatively affect early brain development. This is especially true at younger ages, when learning to talk and play with others is so important” (qtd. in “Television”). B. Explanation Indeed, too much television can be detrimental to cognitive development because preschool-aged children need physical interaction, and television for older children acts as an unhealthy replacement for reading and being read to. Children need to engage in imaginative play; adolescents and teenagers benefit from getting fresh air and being more active. C. So What? While it would be too easy to dismiss every TV show directed at youths—in fact, PBS and Discovery Kids offer excellent programming— children’s lives are increasingly centered around TV-watching, and thus, parents should regulate how much their kids are viewing regardless of content or perceived quality.

- 5. III. Body paragraph #2 - Topic Sentence #2 Moreover, with proper supervision or regulation, there are television programs that can distort a child’s perception of reality. A. Supporting Evidence In the online article “How TV Affects Your Child,” Dr. Mary Gavin (2008) points out that “TV characters often depict risky behaviors, such as smoking and drinking, and also reinforce gender-role and racial stereotypes.” B. Explanation Certainly, seeing these types of behaviors and stereotypes exhibited by favorite television personalities and encouraged by favorite shows can contradict with the values parents want to instill in their children, which can cause both tension and confusion. While television does have entertainment value, children cannot learn all the differences between right and wrong from it. C. So What? Although it is difficult to prevent children’s total exposure to questionable social mores and limited multicultural representation in the media, parents can have

- 6. some control by supervising their children’s viewing as well as talk about what’s portrayed on television. IV. Body paragraph #3 - Topic Sentence #3 Finally, television can impede healthy relationship-building and impose on family time. A. Supporting Evidence For example, recent studies have found that the television is on most of the time in 51% of households and that “[k]ids with a TV in their bedroom spend an average of almost 1.5 hours more per day watching TV than kids without a TV in the bedroom” (qtd. in “Television”). B. Explanation If children are spending this much time glued to the their favorite television programs, and if parents do not have rules about how much is okay to watch, then children are not only spending less time on important cognitive development activities such as reading and doing homework, but they are also spending less time on social interaction with peers and important family time. C. So What? Given how long families are apart from each other during

- 7. the week because of school and work, it is unfortunate that any extra time outside of those obligations should be wasted on watching television; therefore, regulation is one key approach to ensure a family’s closeness and the strength of the parents’ bond with their children. V. Conclusion A. Thesis Statement rephrased Television can be both educational and entertaining for children; however, only in moderation. Thus, it’s important that parents step in to supervise how much television their children watch as it can negatively affect their intellectual, psychological, and social development. 130 ABLVol36No2 2010 Contributed Article Balancing Work, Family and Life: Introduction to the Special Edition

- 8. •John Burgess and Jennifer Waterhouse* The papers in this special edition of Australian Bulletin of Labour are about the issue of balancing paid work with other aspects of life. Work- life had its genesis in the concept of work-family balance in the 1980s, when the apparent tension between work and family life began to be recognised. Woolcott (1990) showed that concerns about issues outside of work, particularly family responsibilities, had the potential to affect both the wellbeing and productivity of workers. Failing to address problems of imbalance between work and other life aspects has also been identified as resulting in detrimental social and economic consequences (OECD, 2008). As a result of these consequences, initiatives that assist workers to balance their work and family lives have gained increasing support from policy makers, employee and employer groups. Early conceptualisations of work-family balance tended to confine research, policy and organisational attention to the matter of conflict between work and the rearing of dependent children. Research has since covered significant terrain, becoming multi-disciplinary, with studies emerging from industrial relations, economics, psychology and human resource management and including topics such as long working hours (for example. Bunting 2005), gender (for example,

- 9. Gregory and Milner 2009) and power (for example, Mescher, Benschop and Doorewaard 2009). *University of Newcastle Burgess and Waterhouse 131 This special edition draws primarily from an industrial relations and policy perspective; but the eclectic nature of the topics covered reflects the diverse nature of the concept. Authors have used both the terms 'work- family balance' as well as the broader 'work-life balance'. This is in keeping with a general trend towards the inclusion of non-family aspects as an important consideration for policy makers, employers and employee groups. The trend is contentious in that the term 'work-life' can be considered a catch-all phrase arguably disguising critical social issues and over-simplifying the complexity and inequity of life inside and outside of paid work such as the gendered imbalance related to child rearing and domestic duties. For the purposes of this special edition, work- life balance is, however, a useful term to capture the full gamut of the topic. The papers provide insights into a wide range of issues, including consideration of the approaches and interventions of various entities at various levels, discussion on the resultant

- 10. or potential outcomes of such approaches and observations about current work- life experience. The study by Skinner and Pocock provides findings from a large Australian survey and highlights the varied experiences of work-life balance for different categories of workers. It provides a useful starting point for themes developed in other articles in this issue. One such theme that also appears in the paper on call centres by Hannif, McDonnell, Connell and Burgess and the study by Brown, Bradley, Lingard, Townsend and Ling is unsociable working hours. The latter study sheds new light on old ground when the benefits of a two-day break are discussed. In this, the study departs from the more common focus on long working hours to a consideration of a need for a long break. All three studies demonstrate the detrimental effects of unsociable hours and the need to deal with this important element in the work-life balance equation. Another common theme is the extension of working hours through the use of informal or unofficial working time arrangements such as that found in call centres, discussed by Hannif, McDonnell, Connell and Burgess. Organisational practice as to working hours and access to work-life policy provisions also forms a major theme of Colley's study of a public sector agency. Of interest in the Colley paper

- 11. is the broadening of organisational policy to encompass a work- life framework; but staff access to entitlements is limited by organisational norms and managerial preference and discretion. Both papers, therefore, highlight the importance of informal practices at workplace level for the extent of workers' access to work- life flexibility arrangements. The main question which these observations on working time and flexibility arrangements raise is the extent to which legislation 132 Australian Bulletin of Labour is able to identify and deal effectively with the informal aspects of organisational practice that adversely affect employees' ability to balance their work and other life activities. The paper by Waterhouse and Colley suggests that the process provisions of the Fair Work Act limit the scrutiny and the enforcement of flexible work arrangements that are necessary to meet the work-life balance needs of employees. It can be argued that the economic and social effects of a failure to address work-life balance (OECD 2008) should extend the topic beyond the interests of traditional stakeholders in industrial relations. Community groups, such as those representing the interests of families, emergency and social

- 12. services, have also sought to contribute to the debate on work-life balance through their contributions to govemment enquiries. The finding by Waterhouse and Colley, that the interests of these non-traditional stakeholders were largely overlooked in favour of traditional actors, suggests the continued view of work-life balance as being more about the needs of industry and the workplace than the needs of society. Much remains to be done in terms of research and practice. The direction for future research is two-fold. First, there is a need for high-level, multi-disciplinary approaches to encompass the intersection of work-life balance in different disciplines. Secondly, and at the other end of the spectrum, is a continued need for investigation of individual cases and experiences. This special edition contributes to this future direction through research that extends from national-level studies, through to industry level and individual organisational cases. References Bunting, M. (2005), How the Overwork Culture is Ruling our Lives, Harper Perennial, London. Gregory, A. and Milner, S. (2009), 'Editorial: Work-life Balance: A Matter of Choice?', Gender Work and Organization, vol. 16, pp. 1-13. Mescher, S., Benschop, Y. and Doorewaard, H. (2009),

- 13. 'Representations of Work Life Balance Support', Human Relations, vol. 63, pp. 21- 39. OECD (2008), Babies and Bosses: Baiancing Work and Family Life, Policy Brief, July. Woolcott, I. (1990), 'The Structure of Work and the Work of Families', Family Matters, vol. 26, April, pp. 32-38. Copyright of Australian Bulletin of Labour is the property of National Institute of Labour Studies and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. Balancing Work–family Life in Academia: The Power of Timegwao_571 283..296 Gudbjörg Linda Rafnsdóttir* and Thamar M. Heijstra In the article we analyse the structuring of time among academic employees in Iceland, how they organize and reconcile their work and family life and whether gender is a defining factor in this context. Our analysis shows clear gender differences in time

- 14. use. Although flexible working hours help academic parents to organize their working day and fulfil the ever-changing needs of family members, the women, rather than men interviewed, seem to be stuck with the responsibility of domestic and caring issues because of this very same flexibility. It seems to remove, for more women than for men, the possibility of going home early or not being on call. The flexibility and the gendered time use seem thus to reproduce traditional power relations between women and men and the gender segregated division in the homes. Keywords: academia, flexibility, gender, power relations, time, work–family balance Women and men often spend their time differently due to the widespread gender division inwork and family life. Thus, Bryson (2007), Kvande (2007) and Davies (1989) emphasize the importance of analyzing the structuring of time and time consciousness when discussing gender equality. Bryson (2007) mentions that the time squeeze can cause decreased autonomy among indi- viduals and diminish their ability to become active citizens. The structuring of time is also a matter of health and wellbeing. According to Frankenheuser (1993) who compared managers in a Swedish factory, women showed the same level of stress as men until the afternoon when the stress increased among women only due to their attempt to reconcile work and family life. As far as gender equality in Iceland is concerned, the country passed an Act on gender equality in 1976 in an attempt to secure the equal input of women and men in society, to work against

- 15. gender-based discrimination in the labour market and to enable both women and men to reconcile work and family life. Today, the Icelandic welfare system is based upon the Nordic welfare model (Esping-Andersen, 1991). In Iceland this includes 9 months of parental leave, of which 3 months is reserved exclusively for fathers, and relatively cheap access to qualified day care for children aged between 1 and 6 years. Each parent is also entitled to ten fully paid child sick days per year. Iceland prides itself on promoting sexual equality and, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (2009, 2010) the country has claimed to be at the forefront of gender equality in the world. The Index benchmarks national gender gaps using economic, political, educational and health-based criteria. It is thus of interest to investigate how career-oriented people such as academics manage to structure their time and combine their work and private life in Iceland. This article revolves around the question whether or not female and male academics use the flexibility at work to balance their work and family life, and if they do, how they do it. To start, we first look more closely at the concept of time. Address for correspondence: *University of Iceland, Faculty of Social and Human Sciences, Oddi, Sturlugata, IS 101 Reykjavík, Iceland; e-mail: [email protected] bs_bs_banner Gender, Work and Organization. Vol. 20 No. 3 May 2013 doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2011.00571.x

- 16. © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Time and gender Our standpoint is that time is multiple and linked to power. That means that we do not see time only as clock time or as linear time that is to be divided into different components. We picture it, rather, as a web where people can move around, at times situated in one compartment, and sometimes in many simultaneously. Power is related to time since time is an essential resource to which access may be unequally distributed. Those who have more power in their relationships are more likely to be able to manage their own time and the time of others in both the private and public realm. The concept of time can be viewed from different perspectives. Bryson (2007), Leccardi (1996) and Davies (1989) point out that so-called traditional time was based on the natural rhythm of the seasons and the tasks that had to be done. The relation to time was local, task-oriented, seasonal and repetitive. With the development of capitalism and industrialization this traditional time consciousness gradu- ally gave way to the modern time of waged workers who were paid for the hours they worked but not on the basis of the tasks they performed or the service they provided. As time consciousness changes, Davies and Bryson argue that time is socially constructed. Davies (1989, p. 17) states: [T]ime consciousness and time measurement are crucial for the structuring and direction of

- 17. women’s and men’s everyday lives. Time can furthermore be used as an instrument of power and control. Former sociologists did not reflect much upon time when discussing the power structures in society. However, a few deal with time, though more obliquely. Frederick W. Taylor (1964) became known for the principle of scientific management or time and motion studies based on breaking a job into its component parts and measuring each to a hundredth of a minute. The ideas behind Taylorism resulted later on in theories like Fordism, principally known as a mass production system theory, and just in time production processes (Watson, 2003 [1980]). Émile Durkheim noted that time is socially constructed and linked to a society that encloses the individual (Durkheim, 1971) and time spent in production is in some ways central to the thought of Karl Marx (1954). Even though these sociologists discuss time, neither of them deals with time as being crucial for their theories, nor do they theorize gender. In contrast, the feministic sociologists Davies (1989), Leccardi (1996) and Bryson (2007) do shed light upon gender when analysing the structuring of time in society. Bryson (2007) points out that the ways in which time is used, valued and understood are central to the maintenance of gender inequalities in public and private life, and are damaging for both men and women. She shows that while parental time with children and leisure in general have increased during the last decades, parents, particularly mothers, partly achieve this by combining the time they spend with their children with other activities. This explains

- 18. why parents perceive themselves as being more and more pressed for time because stress is not simply a matter of the total hours of paid and unpaid work, it is exacerbated by the intensity of their use of time. Parents often have to force different activities into the same period. Bryson refers to Southerton (2003) who has coined the useful term ‘harriedness’ to cover women’s sense of being both harried and harassed by the seemingly incompatible demands on their time and the need to co-ordinate a host of fragmented activities. Davies (1989) argues that there are two major ways of conceiving time in modern society; cyclical (female) and linear (male) time. However, she does note that this generalization may not account for individual cases as they can be much more complex and partially dependent on lifestyle. The linear conception of time — where time is seen as unfolding in a straight and unbroken line, unidirectional and heading towards an unlimited horizon — is the conception that is preponderant today. It appears to characterize men’s relation to time, in terms of the way in which they organize their daily lives as well as their life course. Usually they do so in a much more clear-cut fashion than women. Linear time also forms the dominant structure in present-day society and may be used, as an instrument of power and control over women. Cyclical time, or female time, on the other hand, is usually associated with everyday life prior to, or concurrent with industrialization. Under a cyclical time consciousness people order the events of 284 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

- 19. Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd their lives according to local and natural rhythms and the future is a perpetual recapitulation of the present. The precise measurement of time in these circumstances is superfluous. On a day-to-day basis, people are not subject to clock time but rather to time that is task oriented. According to Davies (1989), the two facets of women’s lives, that is, wage labour and reproduction, are associated with time. She points out that the responsibility that women have for care and reproduction make their daily lives a complex weaving between the dominant linear (male) time on the one hand, and cyclical (female) time on the other. In their experience, this work of weaving time goes beyond economic rationality. Its special quality derives from being at the same time within and outside of economic logic. Davies (1989, pp. 37–8) argues: ‘Time disposal is partly determined by the individual, partly by social or legal coercion and partly through negotiations with others’. Davies shows that since women historically have been responsible for the family, in addition to other tasks, these activities have engulfed all their time due to the temporal nature of care. Women’s time is thereby characteristically others’ time. For these women, doing several things at the same time appears to be the norm. Nevertheless, she maintains that social and legal coercion as well as negotiation with others are closely related to the issue of

- 20. power. Thus, access to one’s own time and to leisure time is quite simply a question of power and may function to enforcer of male identity and provide one of the means by which male hegemony is constructed and reconstructed: The more power and influence we have, the more we can decide over our own time and other’s time, the more we can negotiate time and resist social control. Women’s subordinate position in the public sphere as well as their ascribed role in the private sphere have major implications with regard to this. . . . At home, their time — more than any other family member’s — becomes others’ time . . . both men and women do not and cannot freely choose how to use and structure their time, but . . . for women there are specific structural relations which have special implications for how their time is used. (Davies, 1989, p. 38) Leccardi (1996) argues along the same lines as Davies. She insists that feminist theory calls into question the representation of time in capitalist societies and provides an approach that point to a different conception of the relationship between life and time for both women and men. Women’s biographical time she says, as a result of their increasing capacity to produce income in an indepen- dent manner, is increasingly confronted by the logic, scansions and rhythms of public time. The various dimensions of women’s work are shaped by different forms of logic where family work is governed not by the logic of the market, but by expectations of reciprocity. Even though the clock remains an essential mediator in our everyday existence, its claim to being time per se and its taken-for

- 21. granted hegemony have been undermined. ‘As such, “women’s time” is shown to be “contaminated” by emotions and affections, never to be merely clock time’ (Leccardi, 1996, p. 182). Hassan (2007) connects the discussion about time to new information and communication tech- nologies (ICTs). He points out that the network time provides people with the capability to create their own time and spaces as ICTs and people in interaction undermine and displace the time of the clock. In pre-industrial societies task-oriented time was dictated by the task itself and the interaction between human, technological and local circumstances. Due to the effects of high speed and com- puter technology a network-generated ‘fragmented time’ is emerging alongside the ‘industrial time’ of the clock. Hassan describes the possibilities within these digital spaces to create, experience and control our context-dependent time, where the clock will have marginal or no effect: The important point is that this context-created temporal experience is disconnected from the local clock times of the users. The clock no longer governs, as it once did in the preinformation age. (Hassan, 2007, p. 52) Time use-studies Davies (1989) and Bryson (2007) reveal that the problem with time-use studies in general is that they are based on a view of time in which time can be divided into small measurable components. This PROBLEM REPRESENTATIONS OF EQUAL PAY 285

- 22. © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 makes it difficult to measure tasks that are carried out simultaneously and to measure the time that is involved in caring for others and different kinds of caring responsibilities in which ‘being there’ is important. Bryson (2007, p. 157) stresses: ‘Studies are also unable to record the intermittent worrying, guilt and stress individuals may experience around what they are not doing while they are doing something else’. She highlights that the studies are not able to show the different kinds of time people experience and that all time is not equal. Some people’s time seem to be worth more than others’, which reflects a certain kind of power. Leisure studies are becoming more frequent as leisure appears to play an increasingly large role in the life of adults, at least among the middle class. However, Bryson (2007) notes that, while the rhetoric of time poverty is widely used, writers disagree as to the nature and significance of class and gender-based differences in the availability and nature of free time. In spite of this it is clear to Bryson that the manual working class has less control over its leisure time and does not have access to time-saving resources. This finding is supported by Weigt and Solomon (2008) who compared work and family management among women in low-wage services and female assistant professors at universities in the USA. They found that women privileged by class were also privileged in their

- 23. ability to manage work and family demands. While class muted gendered experiences for the female assistant professors it exacerbated gender experiences for women in the low-wage service sector. Flexibility at work Whenever describing so-called good jobs, the features autonomy and flexibility are often mentioned (Constable et al., 2009). Flexibility at work has basically two characteristics; flexible working hours and telecommuting. Flexible working hours, on the one hand, give employees a certain amount of freedom to decide when to start and end their work day. Telecommuting on the other hand, allows employees to decide where they work, as long as there is an Internet or phone connection (Dickisson, 1997). Autonomy is closely related to flexibility and it has been argued that flexibility at work improves the work–family balance of the worker (Blair-Loy and Wharton, 2004; Reeves et al., 2007). Moreover, some studies show that flexibility decreases stress levels among workers and makes people more productive (Golden and Veiga, 2005; Kurland and Bailey, 1999). Dickisson (1997) notes that employees in flexible organizations take fewer sick days and are often more creative, although he emphasizes the importance of having one’s own work space at home, preferably with a door that can be closed. Kvande (2007) discusses flexibility from another point of view. She points out that especially in knowledge organizations, the shift from standardization to the differentiation of working hours leads to an endless flood of work, long working hours and less family

- 24. time. Kvande refers, for example, to Hochschild (1997) when she points out that the formal contract that regulates working hours is being replaced by moral obligations and time norms that demand total commitment. Blair-Loy (2009) support this findings as her studies shows that stockbrokers in firms with scheduling flexibility experience more work–family conflict than those in firms with scheduling rigidity. Hassan (2007) argues that the reality of network time and network communication for most people is impelled by the need to constantly look for ways to be more efficient and productive. Speed is fetishized and short-term outcomes are valorized. This is in line with Heijstra and Rafnsdóttir (2010), who show that even though ICTs make some features of the life of academics easier, they also initiate a proliferation of the workload, trigger a prolonging of the workday and enhance a demand for extensive availability. While ICTs increase the flexibility of academics at work this does not seem to improve their work–family balance. On the contrary, ICTs and flexibility are found to increase work–family conflict, as the ICTs in combination with their flexibility make it increasingly difficult for academics to disengage from work. Furthermore, according to Pétursdóttir (2009) and Rafnsdóttir (1995) men often have more flexibility at work than women and this improves their autonomy in private and public life. However, most of them do not use this flexibility to reconcile work and family life. 286 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

- 25. Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Academics Being an academic is generally characterized by having a large amount of flexibility and autonomy. Academics have for the most part the freedom to decide where, how and even when to work. Most come close to being their own supervisors even if they are employees. With the arrival of ICTs the possibilities of working from home have increased for them. However, at the same time studies from the UK (Doherty and Manfredi, 2006) and the USA (Jacobs and Winslow, 2004) show that, while academics have a high level of flexibility at work, they also have to deal with an intensification of their workload and long working hours. This might explain why one out of five university teachers in the USA displays serious burn-out symptoms (Lackritz, 2004). A study among university staff in the USA, Canada and UK found that university teachers scored consistently lower on the work satisfac- tion variable and that they were more negative about their workload and work–family balance than other university staff (Horton, 2006). Furthermore, in a study among 18 female Michigan university teachers, participants were asked how they managed to balance career and family demands. ‘Getting used to little sleep’ turned out to be the key answer (Damiano-Teixiera, 2006). Sleepless in academia is the title of an article by Acker and Armenti (2004) in which they present two Canadian studies

- 26. on academics. In these studies women emphasized high stress levels, exhaustion, fatigue and sleeplessness in association with building an academic career and bringing up young children simultaneously. Working harder and sleeping less were the main responses when participants were asked how they coped at the univer- sities. Acker and Armenti point out that these coping strategies can cause illness among women. The men in the study were less likely to describe illness and their jobs seemed not to be tearing them apart in the same way as they did in women. In academia in Iceland the working hours are unregulated and the work is to a large extent product oriented. Academics get monthly wages but they also get a bonus payment once a year for performing certain tasks, such as publishing peer-reviewed articles in highly ranked international journals. The pressure to publish has been intensified by actions that reward or punish the individual university teacher and departments on the strength of research productivity. The remaining part of the article revolves around our study and the question whether high flexibility at work influences the way in which academics in Iceland manage their time and how they reconcile their work–family balance. By emphasizing gender in this context we focus on everyday experiences at work, family and leisure time of the academics interviewed and explore whether or not gender meanings shape their time structure. Method

- 27. The study is based on 42 semi-structured in-depth interviews with academics and top managers in private Icelandic companies. In this article we focus on the 20 academics interviewed, 10 women and 10 men. The academics are from different faculties and different universities. They are employed full time and rank either as lecturer, senior lecturer or professor. They are all parents and most of them have two to four children varying in age from 6 months to a little over 20 years. According to Statistics Iceland (2011) the fertility rate among Icelandic women in 2010 was 2.2, which is higher than in other Nordic countries and among the highest in the western world (Eurostat Demographic statistics, n.d.). The average fertility rate of the academics interviewed was 2.7. One of the participants was a single parent and all the others were married or cohabiting. Most of the interviews were done in or around the universities, but some took place in the participants’ homes. The interviews, which lasted between 25 and 90 minutes, were tape-recorded, transcribed and analysed according to grounded theory. Smith (1987, p. 99) quotes Marx and Engels stating that ‘Individuals always started, and always start, from themselves. Their relations are the relations of their real life’. In accordance to this, we focus on the interviewees’ everyday life when analysing their structuring of time in the academy. We PROBLEM REPRESENTATIONS OF EQUAL PAY 287 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013

- 28. asked them, among other things, about the organization of their work, work procedures, flexibility, leisure and family life, housework and childcare arrangements. Regarding anonymity, performing qualitative research in a small community is not easy. The academics’ freedom of speech was based on our commitment to anonymity, which is quite complex in Iceland as there are only seven universities and a few hundred tenured academics. In order to strengthen anonymity, we have therefore decided not to describe our interviewed professors as precisely as we would have done in larger communities. The only information pre- sented here is whether the participants are male or female and if they have small children, teenage or grown-up children, or both. To give the reader further information could put the anony- mity of the interviewees into jeopardy. We believe that the information given will be sufficient for the reader to understand the topics we are presenting in the article. Like Smith (1987) we are constrained by our commitment to ensure that the academics we spoke to speak again in what we write, like active and reflective subjects, despite our reinterpretation of what they had to say. Findings This section discusses the findings from the study with the interviewed academics. We start from the basic assumption that social life (Berger and Luckmann, [1966] 1987) and time (Bryson, 2007; Davies, 1989) are socially constructed and linked to power.

- 29. Flexibility The academics in our study generally enjoy a high level of flexibility at work. They refer to this flexibility as one of the main advantages of working in academia. They feel that the flexibility helps them to balance work and family life. Nonetheless, the female participants seem to utilize this flexibility in different ways from the men. Even if there have been certain changes during the last years between women and men regarding the division of housework and childcare, it may not be as much as we would like in terms of gender equality. For instance, mothers are more likely than fathers to use this flexibility to be on call for the family. Ólöf, an academic mother of both young and teenage children, explains how flexibility at the university helps family life to continue. She says: I always came home early . . . he, [her husband] couldn’t do it himself and in the past I have always taken more days off when the children were sick because my workplace is more flexible. Here Ólöf points out that because her husband does not have the same flexibility at work as she does it is always her duty to be on call. The academic male participants that also have this flexibility do not mention, as some of the women do, that it is their primary obligation and not their partners’ to be on call. However, they do stress that their flexible working schedules are good for their family. Their wives seem to take the primary responsibility for the household and for ‘being there’, independent

- 30. of whether they themselves have flexible schedules or not. This probably explains why some of the women interviewed praise their flexibility but at the same time point out that, unlike the men, they do not have flexibility as individuals because their time schedule is too tight. ‘I think it is probably more in my mind than it is in reality [that I can decide] when I work and where I work’, says Maria, one of the academic mothers with both young and grown-up children. Even though the participants mention that the flexible working schedules and telecommuting improve their work and family balance, it turns out that those work characteristics lengthen their workday and prevent them from spending time with their family without having work-related issues on their mind all the time. 288 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd A double-edged sword When asking about the negative side of the unregulated working hours we see that what is felt as the most positive aspect of their work, that is, the flexibility and the freedom to work ‘whenever and wherever’, is also the most negative aspect. The unregulated working time in the academy thus feels like a double-edged sword:

- 31. [The] disadvantage, of course, is that it’s much more difficult to keep a clear distinction between your free time and your work time and if you are not careful, all your time will be swallowed up by work. (Tómas, an academic father of small children) Sigurdur, also a father of small children says: ‘You are never off’. Johanna, a female colleague with small children, has similar thoughts in relation to her workload: I think [the workload] is too much. . . . So what I do in the evening is to write, try to write some articles. So I feel like I am doing all of that just in my free time. Interestingly enough, Johanna argues, however, that the balance between her work and family life is good, but she adds: It has to be at the expense of feeling that I haven’t done anything except work and be with the kids. After saying this, she points out that having children was something she decided to do: ‘Of course, it was my choice’ she says. This is a remarkable statement which we find in several of our interviews with women. Some of them seem to feel that they were not allowed to complain about a heavy work–family workload because it was their choice to have children. None of the interviewed fathers refer to their own liability for having children when discussing the combination of work and family life and long working hours. Regardless of how many children the academic fathers have, and even if they do some of the household chores, they are less likely

- 32. than the academic mothers to say they have a heavy family workload. The flexible working hours and the possibility of going home early to care for the children and the household before they continue working in the evenings are praised by both women and men. However, women are more likely than men to express time poverty and lack of personal time: Last winter, and even more the year before that, I felt that I never had time for myself to read a book or do anything besides just working and being with the kids. And, you know, when they are small it’s like, it’s of course very nice being with your children but it’s still a lot of work, you know, doing all that. (Ólöf) Working always and everywhere Even if some scholars like Dickisson (1997) stress the importance of having a separate room in the home to work in, most of the academics choose to work where the family was even if they have a separate room. Favourite places to work in are the living room, the children’s bedroom and the kitchen. Working where the family is can partly be explained by the fact that academics, especially women, work ‘in bits and pieces’ at home. This means that they work whenever they get the chance and they feel it is easiest to do this by having the laptop closely at hand in the places where they most often are, that is, in the living room or the kitchen. Based on the interviews, working everywhere also seems to be a way for these academics to hide from themselves and their families the fact that they are

- 33. constantly working. They hope that their families may not experience it as work when they are ‘playing on the laptop’ in front of the television or in the kitchen. In addition, for the academics themselves it feels more as if they are supporting their family when they do not isolate themselves in a separate room. Maria, who always has her laptop with her, says: ‘I am on the computer in bits and pieces if I am at home’. Ragnar, a father of small and grown-up children, says: PROBLEM REPRESENTATIONS OF EQUAL PAY 289 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 The laptop fits everywhere . . . we have an office at home but I don’t use it much. I work . . . in the living room, I have my laptop in the couch. Nevertheless, how well the academic parents are able to work while their children are around varies. Tómas, who works a lot at weekends, says: I like waking up early on Saturdays and Sundays, then the kids want to watch TV. So maybe I will just take my computer and sit with them for 2 or 3 hours. I get a lot of work done and they are just . . . watching television. The quote shows that his children do not interrupt him while he is working but he feels he is supporting the family by his presence. Other parents give

- 34. examples of how they integrate work and childcare, even in the children’s bedroom. Helena, a mother of both young and teenage children says: I often take my youngest daughter to bed . . . and then I bring with me an article, books . . . so while she is falling asleep I am reading something I need to read up for work. Johanna says: Last winter I worked every single evening and it was very difficult to do that, but, I mean, that was just the price, really, that [I] had to pay for leaving work so early. She usually picks up her children from preschool in the afternoon and experiences her university work in the evenings as the ‘price I have to pay’ for this. The men interviewed do not say that working in the evenings is the price they have to pay. Magnús is a father who has both young children and teenagers. He says: A long work week really means that you have a lot of time to work on things that you added, you know, you are working on it because you decided to and that’s what you like to do, and that’s why you are doing it. Unlike Johanna, Magnús says that he has power over his own working time. He works long hours because he likes it and has decided to do so. Working late in the evening is not a consequence of the time he has to spend with his family.

- 35. The official summer leave in Iceland is 5 to 6 weeks for academics, depending on their age. As in other Nordic countries, many employees take these 5 to 6 weeks for their summer vacation but also make sure that they have some days left that they can use as a Christmas break. However, this is not the case for most of our interviewees. Ólöf says: Actually when I started working here, I asked a lot of people, ‘How much time do we have as a summer vacation?’ And nobody really knew that, and I was like, ‘Ooh, that’s very interesting’. She continues: I feel sometimes like . . . the atmosphere here is that you are not supposed to have any family life. Sometimes I feel like I can read between the lines . . . that people who are working in the university . . . should always be working. . . . And I feel a little bit like it’s prestigious in this institution not to take a summer vacation or not to know when you are going to take it. She mentions that when you have children you must take some days off: ‘Having the kids forces you a little bit to take vacation, which I think everyone should do anyway’. Helena says that it is a conscious effort not to work during the summer vacation. She usually takes some books with her and the laptop when she is on leave. But her husband doesn’t like her working when the family is on vacation and she usually makes an agreement with him about how much she can work. She tries to convince him that her work during the vacation is in the interest of the family:

- 36. I got that piece published and now I was getting my points and I was telling my partner, you know, ‘Just for this article we get this much money’. [Laughs] 290 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd The interviewed men do not express the need to justify their work to their wives or their family. The wives of these academic men in general seem to have a better understanding of the ‘endless work’ than the academic women’s husbands.1 Furthermore, the academic women express more guilt over working at inconvenient times than their male colleagues. We interviewed the academics’ partners, to bring to the light their views on academic working schedules, flexibility and the work–family life balance. Actually none of the men interviewed talked about remorse in relation to their family because of their long working days. The reason for this might be that some of the men still considered themselves to be the main breadwinners, even though their wives or partners worked full time and had their own income. The breadwinner role thus releases them from the main responsibility for the household, even if they participate in the household tasks allocated to them. Maria often comments that she is the main breadwinner in the family. However, this does not free her from having the main responsibility in the household, which

- 37. she believes is unfair. It would be interesting to know whether her partner also considers her as the main breadwinner, or whether he feels that he is the main breadwinner even though he earns less than she does. Sigurdur often refers to his father when describing why he likes to work long days even during family vacations. His father liked to work a lot, and so does he. The female academics do not refer to their mothers or fathers when describing their long days at work. Quite the opposite, their image of a good mother rather seems to make the women express bad feelings about their heavy workload. The time that never comes The academics interviewed define their workload at the university as heavy because ‘you have never done enough’. Maria says: I started to have health problems due to too much work and some heavy family responsibilities. . . . I am working my ass off. Of course, I am working because I like it. Like Johanna, who prefers to stress that she chose to have children, when explaining the struggle for mastering the work–family balance, Maria underlines that she likes her job when talking about her workload. In both cases these remarks are like excuses that tone down their complaints and leave images of a problem that is self-inflicted. What remains is that these women blame themselves for being unable to balance their work and family life. The women and the men describe their workload differently.

- 38. Even if both genders say they work about 60 hours a week, the men seem to get more support for their long working schedules and they seem to bear less overall responsibility for their work within the family. The women are more likely to make a formal or informal agreement with their family members while working during periods when the family expects them to be off, while the men’s working time seems to be more on their own premises. Some of the women interviewed express struggles in their work–family life, while they are fighting to create time for their work and for their family to become more engaged in the household. Iris, a mother of both young and teenage children, says: ‘I think there is always gonna come a time when things are better [laughs]. I always have that idea but that time never comes’. She is referring both to her husband and her teenagers, whom she feels take little responsibility in the household. In Icelandic academia research points are very important. As mentioned above, Johanna convinced her family that finishing an article during a family holiday is in their best interest, and not without good reason. Research points are built into the structure of their wages, increasing the possibilities to get grants and speed up the advancement process in the academic career hierarchy. Also, research points make it easy to keep track of who is productive and who is not, and who publishes in highly ranked journals. It seems to be more of a struggle for the female participants in this study than for academic males to earn an acceptable amount of research points each year, which consequently brings about lower wages and slower career advancement. Hildur, who has teenagers and has been

- 39. working for many years in academia, supports this: ‘On the whole, I mean, this job suits me but [it is] very stressful, you know, I get very stressed’. PROBLEM REPRESENTATIONS OF EQUAL PAY 291 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 Maria, who is younger than Hildur and has been working in academia for only a few years, is critical of the structuring of time and the workload: You look at things and think, ‘How much am I willing to sacrifice? I am not going to sacrifice my family completely. I am not going to sacrifice my health to be this excellent researcher with the most prestige. No. . . . I am not going to hang the whole of who I am onto how many points I get. And I am not gonna, you know, compare myself all the time with somebody else’. However, Maria has had health problems due to workload, as remarked before. None of the partici- pating men reflect on their work as a threat to their health or family life and they do not seem to question equating their work with who they are. They do not express any sacrifice or struggle when talking about overtime, research points and their everyday life. When discussing work development and promotion Johanna said: Of course, it is sometimes annoying when young boys . . . [speed up the career ladder], and you

- 40. think, oh my God, they’ve been carried in this world. . . . I don’t wanna sound like a bitter woman or something but, I think, for a lot of us women, we had to fight to do what we love doing and to get a position that enables us to do what we like doing. A lot of support, and a lot of criticism. Ragnar supports this view, referring to old role models and social control. He refers to his colleague who said that ‘being an academic was perfect for bachelors . . . with wives’. This is certainly a joke but one of these jokes that academics can easily identify with. Managing time It is interesting to notice that the men interviewed in general were more likely than the women to say they had power over their own time, and they seem to allocate that time between the family and their work much more easily than the women interviewed. The men approach their work and family life more like different projects in which they decide for themselves when to start and when to finish. Even though they are responsible for different household chores, they appear to be better able than the women to divide their time between these tasks without bearing the generic responsibility for them. Their time, unlike the women’s time, seems to be divided into different projects on a timeline. The men’s time seem in general to be what Davies (1989) calls linear time: If I am given a project to take care of I do it, even if that project has to do with the family I do it . . . I happily do it. That’s probably my way of managing the balance between work and the family, to

- 41. create projects. Here Sigurdur describes his participation in the household. Someone gives him a project in the family. Sigurdur is actually referring to his wife. He was far from being the only one who used this rhetoric, which seemed though to be quite gendered. Tómas said this about how he used the flexibility at the university: ‘Of course when they [the children] are sick and so on, you sometimes are in a position to take leave from work’. Tómas is ‘sometimes’ in a position to take leave, indicating that he has the choice not to take leave when his children are sick if he is bound to other projects. Pétur, another father of young children, says: To be completely honest, I am not very good at balancing work and family life, but what I try to do is to be available when needed. This utterance indicates that Pétur, like Tómas, has the choice not to be available. In general, the academic men, as opposed to the academic women, participate in paid work for longer hours than their partners and thus have in general higher salaries. So, even though the men in academia do not necessarily work more than their female colleagues they seem to get more support from their partners than the academic women, who are more or less bogged down in their daily time-consuming routines 292 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing

- 42. Ltd and family responsibilities besides their work. When Maria is commenting on the structuring of time in academia she says: ‘it’s not a good deal for most women, I think’. What she is referring to is that the unequal distribution of responsibility within the family together with the endless stream of work in academia creates an unhealthy workload for women. Similar to how I feel about being a mother It turns out that a typical workday in academia does not exist. Nothing is normal, every day is very different. ‘The only thing that is constant is too little time and too many tasks’, says Iris. The academics workday generally continues into the evening or even into the night. They work in the evening because there is ‘this endless stream of work’, but also because the evenings and the nights are times when they are not interrupted and can work in relative peace and quiet. When asked about the end of the workday, Andrea, a mother of adolescents, says: Never . . . when I fall asleep. . . . I don’t quit at five because I work at home . . . if there is something I want to do, or need to do, I work at night. She doesn’t quit when she leaves the university because she brings her work home with her in the afternoon. The possibility of working at home seems to lengthen her working day. Maria says, ‘I am always working when I am not asleep’. Ólöf

- 43. takes a few days off when she feels too tired and Iris states that when she starts dreaming about work or isn’t able to fall asleep because of work, it is time to take a day off. Eirikur, a father of adolescent children, affirms that he does not mind long working hours as long as he can be creative. Iris supports his statement by revealing that when she gets into the writing mood she writes non-stop. Hildur has had health problems, probably because of a work overload, and she tries to follow the advice of her physical doctor of only saying ‘yes’ to projects and things she likes. However, she feels that this is easier said than done. It turns out that many participants do not see their profession as a job but rather as many different jobs or even as a lifestyle rather than work. ‘Being an academic is a way of life’ is a common phrase. Some mention that their profession is a part of their identity, something they cannot just switch on and off. Iris says: In many ways it’s the same thing as, or similar to how I feel about being a mother: it is not a real job, it is who I am, you know. Defining work as a hobby or a life style is probably a way of escaping the fact that the work tends to drown both their families and their private lives in general. Discussion and conclusion In this article we have analysed how academics in Iceland structure and use their time and reconcile their work and family life. We have found that in general the

- 44. male participants manage their time better than the female participants, independently of their age or the number of their children. On the other hand, time poverty is prominent among both the women and men interviewed, even if the academic women placed stronger emphasis on time scantiness, as well as on fragmented and constrained leisure and working time. Earlier we referred to Bryson (2007), who argued that time is linked to power. Our interviews with women and men in academia support that view, as well as the argument that time is linked to gender. We also notice the paradox that at the same time as the flexible working hours help academic parents to organize their working day and fulfil the ever-changing needs of family members, the women, rather than the men interviewed seem to be stuck in the responsibility of domestic and caring issues; indeed, because of this very same flexibility. The flexibility seems to remove, more from women than men, the possibility of going home early or not being on call. This flexibility and the gendered time PROBLEM REPRESENTATIONS OF EQUAL PAY 293 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 use seem thus to reproduce traditional power relations between women and men and the gender- segregated work division in their families. This probably explains why the men interviewed seemed to be more relaxed and happy with the structuring of their time

- 45. than their female colleagues, despite their high workload. ICT encourages academic teachers to bring work home thereby blurring the boundaries between family life and work. But, interestingly, this has in general different consequences for each gender. Davies wrote during the 1990s that women’s time at home ‘becomes others’ time’ (1989, p. 38). Our data, collected more than 20 years later among highly educated women and men in a country that scores the highest on the gender gap index show that men are still more able than women to be off work when home, either to recharge their batteries or to work, if they like. Our finding is also in accordance with the 20-year-old Swedish study of Frankenheuser (1993), who found that women managers experience more stress than men while attempting to balance their work and family life. Even if the men in our study take care of their children and perform different household tasks, we also find similarities with Leccardi (1996) who, in the final years of the 20th century, claimed that ‘women’s time’ is shown to be ‘contaminated’ by emotions and affections, rather than clock time. To conclude, when analysing our data, we do not get full support for the assertion of Reeves et al. (2007), Blair-Loy and Wharton (2004) and Golden and Veiga (2005) that flexibility improves the work–family balance, in the sense that this flexibility brings a lot of their work into their homes and diminishes their possibility not to be on call. It also does not necessarily support Golden and Veiga’s results that flexibility decreases stress levels, because working during supposed family time can

- 46. create stress and strain. In both cases, however, this could be more legitimated for men than for women. Our results can support Blair-Loy (2009) who points out that even if the common finding is that workplace flexibility reduces work–family conflict, this is not generalizable for all occupational groups. As our study is based on only 20 interviews with female and male academics, we cannot generalize our results to other occupational groups or to differences between men and women in general. However the results highly support Kvande (2007), who stresses the importance of analysing the gender aspect of flexibility, and Davies (1989) and Bryson (2007), who show the gender aspect of the time. In future studies it would be of interest to include academics who do not have children to see if we notice similar patterns regarding the power of time among couples without children. However, there are only few in Icelandic academia, as it is uncommon for married or cohabiting Icelandic women to choose not to have children because of their career. It is important to stress that even though we question the assertion that flexible and autonomous working schedules improve the work–family balance, we cannot claim that this flexibility makes maintaining the balance more difficult. This sounds like a paradox and leads us to rethink the widespread results of much work–family and flexibility research where we have to take gender power and occupation into closer consideration. In her study Rafnsdóttir (1995) referred to men’s greater flexibility and mobility at work when describing the fact that the gender division of labour in the

- 47. fishing factories leads men to jobs that have more autonomy than the jobs women have. In our study we are not dealing with a gendered division of labour, as women’s and men’s work in the academia were fully comparable. So the contribution of this study to former studies is that, even when comparing highly educated women and men in the same kind of work, that is, academics, men seem to have more personal autonomy than their female colleagues and they are better able to utilize this autonomy for their own interest. The flexible working schedules seem to accentuate the gender role and reproduce unequal gender power. Acknowledgements We thank the University of Iceland Research Fund for supporting the study, and the two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments. We would also like to thank the academics who gave us access to their valuable time and important reflections. 294 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Note 1. We interviewed the academics partners to bring to light their views on academic working schedules, flexibility and the work–family life balance.

- 48. References Acker S. and Armenti, C. (2004) Sleepless in academia. Gender & Education, 16,1, 3–24. Berger, P. and Luckmann, T. (1987 [1966]) The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. Blair-Loy, M. and Wharton, A. (2004) Organizational commitment and constraints on work–family policy use: corporate flexibility policies in a global firm. Sociological Perspectives, 47,3, 243–67. Blair-Loy, M. (2009) Work without end? Scheduling flexibility and work-to-family conflict among stockbrokers. Work and Occupations, 36,4, 279–317. Bryson, V. (2007) Gender And the Politics of Time. Feminist Theory and Contemporary Debates. Bristol: Policy Press. Constable, S., Coats, D., Bevan, S. and Mahdon, M. (2009) Good jobs. London: The Work Foundation. available online at http://www.theworkfoundation.com/research/publications/public ationdetail.aspx?oItemId=226& parentPageID=102&PubType= Last accessed 3 December 2009. Damiano-Teixiera, K. (2006) Managing conflicting roles: a qualitative study with female faculty members. Journal of Family and Economical Issues, 27,2, 310–34. Davies, K. (1989) Women and Time. Weaving the Strands of Everyday Life. Lund: Grahns Boktryckeri. Dickisson, K. (1997) Telecommuting got your homework done? Benefits of a flexible work option that is gaining

- 49. currency in the ’90s, and how to get around its potential pitfalls. CMA Magazine, 70,10, 13–14. Doherty, L. and Manfredi, S. (2006) Action research to develop work–life balance in a UK university. Women in Management Review, 21,3, 241–59. Durkheim, E. (1971) The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. London: SCN Press. Esping-Andersen, G. (1991) The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Eurostat Demographic Statistics. (n.d.) Total Fertility Rate 2007. Available online at http://epp.eurostat. ec.europa.eu/tgm/graph.do;jsessionid=9ea7974b30dcf5dc3a9aa1 7b44ac842c818816276241.e34SbxiPb3uSb40L b34LaxqRaxyTe0?tab=graph&plugin=1&language=en&pcode=ts dde220&toolbox=type, last accessed 15 December 2009. Frankenheuser, M. (1993) Kvinnligt, manligt, stressigt. Höganäs: Bra. Böcker. Golden, T. and Veiga, J. (2005) The Impact of extent of telecommuting on job satisfaction: resolving inconsistent findings. Journal of Management, 31,2, 301–18. Hassan, R. (2007) Network time. In: Hassan, R. and Purser, R. (eds) 24/7. Time and Temporality in the Network Society, pp. 37–61. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Heijstra, T.M. and Rafnsdóttir, G.L. (2010) The Internet and academic’s workload and work–family balance. The Internet and Higher Education, 13,3, 158–63. Hochschild, A.R. (1997) The Time Bind. When Work Becomes Home and Home Becomes Work. New York: Henry Holt.

- 50. Horton, S. (2006) High aspirations: differences in employee satisfaction between university faculty and staff. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 1,3–4, 315–22. Jacobs, A.J. and Winslow, S.E. (2004) Overworked faculty: job stresses and family demands. The Annuals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 596,1, 104– 29. Kurland, N. and Bailey, D. (1999) Telework: the advantages and challenges of working here, there, anywhere, and anytime. Organisational Dynamics, 28,2, 53–68. Kvande, E. (2007) Doing Gender in Flexible Organizations. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget. Lackritz, J. (2004) Exploring burnout among university faculty: incidence, performance, and demographic issues. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20,1, 713–29. Leccardi, C. (1996) Rethinking social time: feminist perspectives. Time & Society, 5,5, 169–86. Marx, K. (1954) Capital. Vol 1. London: Lawrence & Wishart. Pétursdóttir, G.M. (2009) Within the aura of gender equality: Icelandic work cultures, gender relations and family responsibility. PhD dissertation Faculty of Political Science. Reykavík: University of Iceland. Rafnsdóttir, G.L. (1995) Kvinnofack eller integrering som strategi mot underordning. — Om kvinnliga fackföreningar på Island (Women’s Strategies for overcoming subordination. a discussion of women’s unions in Iceland). Lund: Lund University Press. Reeves, R., Gwyther, M. and Saunders, A. (2007) Still juggling after all these years. Management Today, 36–42.

- 51. Smith, D. (1987) The Everyday World As Problematic: a Feminist Sociology. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press. Southerton, D. (2003) ‘Squeezing time’: allocating practices, co-ordinating networks and scheduling society. Time & Society, 12,1, 5–25. PROBLEM REPRESENTATIONS OF EQUAL PAY 295 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 Statistics Iceland (2011) Fertility 1853–2010. Available online at http://www.statice.is/Statistics/Population/ Births-and-deaths. Last accessed 17 April 2011. Taylor, F.W. (1964 [1903]) The Principles of Scientific Management. New York: Harper & Row. Watson, T.J. (2003 [1980]) Sociology, Work and Industry (4th edn) London: Routledge. Weigt, J.M. and Solomon, C.R. (2008) Work–family management among low-wage service workers and assistant professors in the USA: a comparative intersectional analysis. Gender, Work & Organization, 15,6, 621–49. World Economic Forum (2009) The Global Gender Gap Report (2009) Geneva: World Economic Forum. World Economic Forum (2010) The Global Gender Gap Report (2010) Geneva: World Economic Forum. 296 GENDER, WORK AND ORGANIZATION

- 52. Volume 20 Number 3 May 2013 © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd Copyright of Gender, Work & Organization is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.