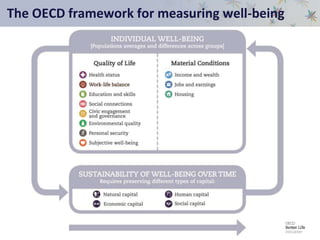

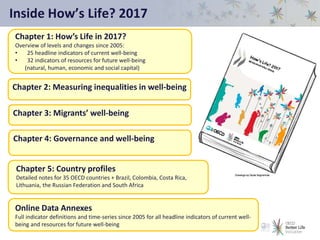

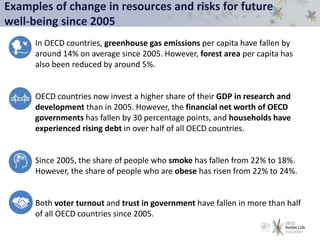

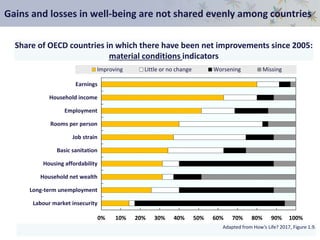

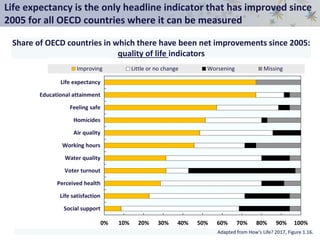

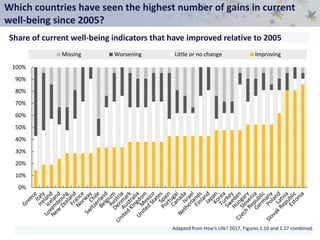

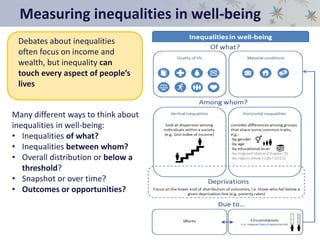

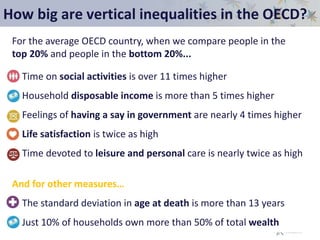

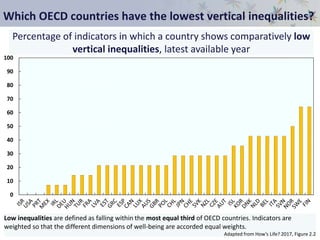

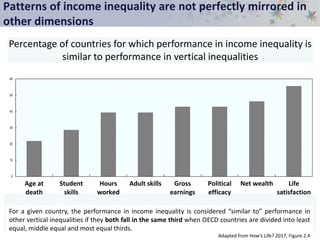

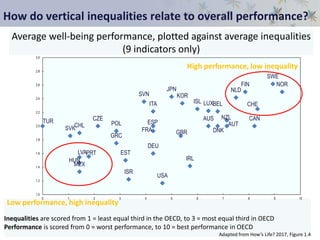

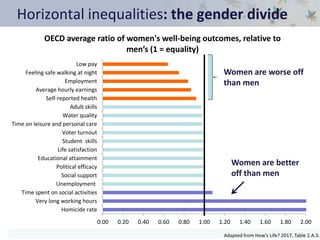

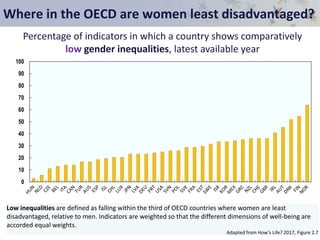

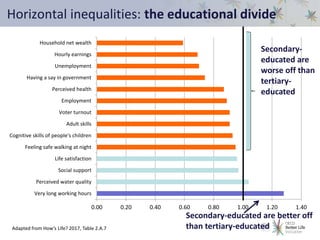

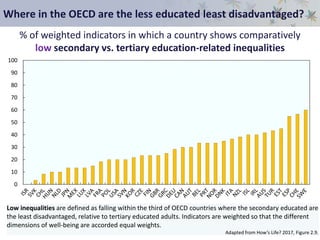

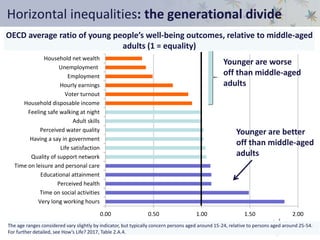

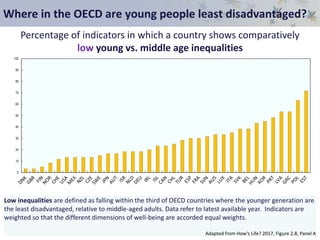

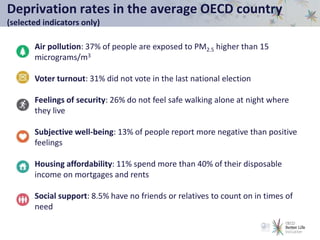

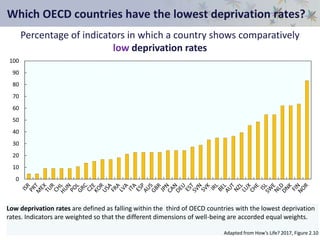

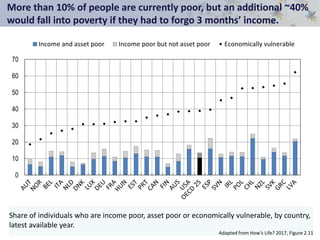

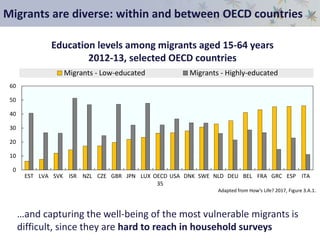

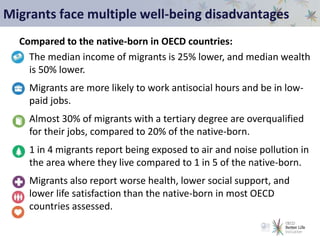

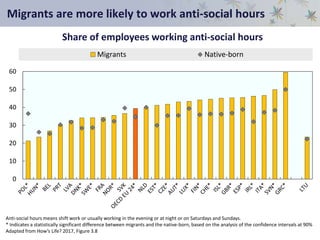

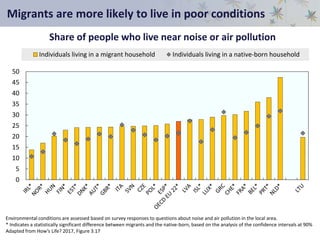

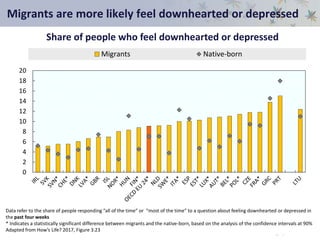

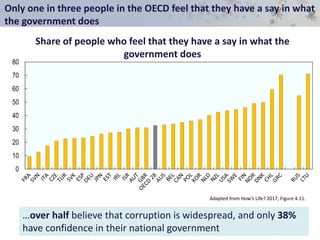

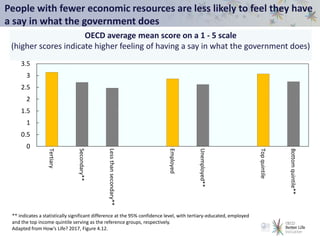

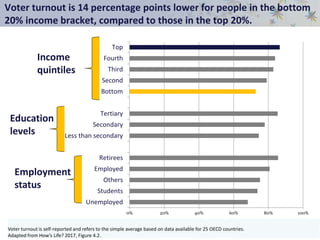

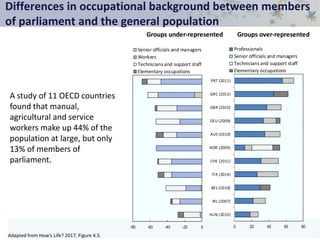

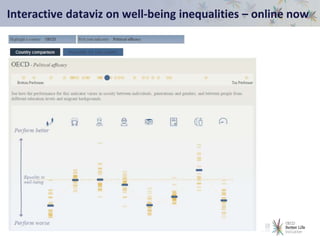

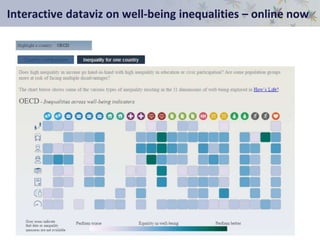

The OECD's 2017 'How's Life?' report measures well-being through a framework focusing on people's outcomes across 25 indicators, tracking changes since 2005 and inequalities among various demographics. The report highlights that while some aspects of life have improved, progress is uneven and significant disparities exist across gender, education, and age groups. Additionally, migrants face distinct challenges, including lower income and social support compared to natives, underscoring the need for a comprehensive understanding of well-being beyond economic metrics.