Spontaneous pneumothorax

- 4. •

- 5. •

- 6. •

- 7. •

- 8. •

- 9. •

- 10. •

- 11. •

- 12. • After the first episode of PSP, recurrence varies, ranging from 16% to 54%. Most studies indicate an average of 30%.14,15 Recent research indicates that the presence of subpleural blebs on high-resolution CT confers a recurrence risk of up to 68.1%, whereas the absence of blebs carries a recurrence risk of only 6.1%.16 Most recurrences develop between 6 months and 2 years after the initial episode.15 Men who are tall and have a history of smoking are at the greatest risk of recurrence. Counseling for smoking cessation should be strongly encouraged.15 After the second episode of PSP, the likelihood of recurrence increases markedly and can reach as high as 83%

- 13. •

- 14. • A giant bulla mimicking pneumothorax on a radiograph in a 67-year-old man. He has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a cigarette smoking habit. a A giant bulla appears as an oval radiolucency (black arrows) in the right lung apex on an erect radiograph. It resembles pneumothorax in the apicolateral space. Bullous emphysema exists in both lungs, and a large bulla is observed in the left lung apex (arrowhead). b A coronal CT image reveals a giant bulla (black arrows) in the right lung apex. A large bulla (black arrowhead) also exists in the left lung apex in addition to bullous changes in both lungs

- 15. •

- 16. • Learning points • Bullous emphysema is typically seen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and when bullae occupy more than 30% of hemithorax, they are called ‘giant bullae.’2 • Giant bullae can mimic pneumothorax and a CT scan is required in such cases to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary procedures. • An important differentiating factor between these two entities on imaging is that the lung collapses towards the ipsilateral hilum unless there are adhesions in case of pneumothorax, while the lung is draped around the bulla with the giant pulmonary bulla.3

- 17. •

- 18. • Observation Small pneumothoraces are those that are less than 3 cm in distance between the apical parietal pleura and the thoracic cupula, with no lateral component. Asymptomatic patients should be managed expectantly26-28 by close monitoring, physical examination, continuous pulse oximetry, and repeated chest radiography within 3 to 6 hours.

- 19. • Residual apical pleural space was determined by measuring the lung apex-to- cupola distance (double-headed arrow), which is the vertical distance from the 1st costovertebral joint to the tip of apical lung.

- 20. • The ACCP recommends against the placement of chest tubes, or aspiration of small pneumothoraces. Our practice is to monitor patients in the hospital for a minimum of 24 hours. Even though some patients with stable radiographic features may be discharged from the hospital with follow-up within 12 to 24 hours,16,26 the potential for catastrophic consequences from a missed tension pneumothorax is a great risk.29 Small pneumothoraces usually resolve without intervention, but recurrence is possible. If chest radiography reveals that the SP is enlarging, immediate intervention is crucial

- 21. • Aspiration Aspiration allows evacuation of pleural air and complete reexpansion of the lung. This technique can be applied even for larger pneumothoraces if the patient is stable. We prefer the Seldinger technique,30,31 which uses a small, single-lumen central line placed over the superior rib edge in the second interspace in the midclavicular line. A three-way stopcock and large syringe are used to aspirate until resistance is felt, usually signifying full lung expansion. Chest radiography is then performed to confirm the findings, and the catheter is removed.27,28,32-36 Commercially prepared kits with one-way valves (Heimlich valve)7 allow air to exit but prevent air entry. These valves can be left in place until full lung expansion is achieved. For more rapid resolution, however, it is our preference to perform tube thoracostomy with a small chest tube. Complications of aspiration, although rare, may include bleeding and possible lung injury. Reported success is higher in resolving PSP (66% to 83%) than for SSP (37%).27,35 SP that does not respond successfully to aspiration requires tube thoracostomy

- 22. •

- 23. •

- 24. • Tube Thoracostomy Tube thoracostomy is recommended for patients with large or symptomatic SP and for most patients with SSPs. Patients with signs of a tension pneumothorax should be treated without hesitation, even before chest radiography is performed. Tube placement is through the fifth intercostal space in the midaxillary line. In our experience, as with chest tubes placed through port sites following VATS, there is no need to tunnel chest tubes placed at bedside

- 25. • A small chest tube can be difficult to direct to the apex of the chest, so a 28 Fr is preferable. The chest tube is left in place for 24 to 48 hours. Our practice is to place the chest tube on water seal once lung expansion has been confirmed. If an air leak persists and nonoperative management is preferred, a Heimlich valve can be placed The patient can then be discharged for outpatient management. The efficacy of suction is debated, but there is no evidence that it speeds the resolution of SP. If it is used, it should be used judiciously.37 • Tube thoracostomy successfully resolves PSP in approximately 90% of patients for the first occurrence, 50% for the first recurrence, and 15% after a second recurrence.38 For this reason, definitive management of SP recurrences will require either surgical intervention or chemical pleurodesis.

- 26. • Pleurodesis After tube thoracostomy, chemical pleurodesis may help prevent SP recurrence. Sclerosing agents are instilled to create pleural symphysis. The most commonly used agents are sterile talc slurry and doxycycline solution. Because adult respiratory distress syndrome may be triggered by high doses of talc, use should be limited to

- 27. • In theory, talc has the potential to induce malignant transformation after decades of use, but thus far, this has not been demonstrated in humans.41 Nonetheless, our agent of preference is doxycycline to sclerose benign pleural processes. A total of 500 mg of doxycycline combined with lidocaine is infused through the chest tube, and the patient’s position is shifted from side to side to distribute the sclerosant. Suction is then placed for 48 hours. Recurrence of SP in patients treated with bedside pleurodesis is high, ranging from 8% to 40%.40,42,43 In our institution, this treatment is reserved for patients who are not considered good operative candidates, most commonly patients with SSP.

- 28. •

- 29. • Surgery Surgical indications for PSP are recurrence, large or persistent air leaks, and incomplete lung expansion after tube thoracostomy. Other surgical indications include patients with a history of bilateral SP and patients in occupations that would place them at high risk if a pneumothorax recurred, such as commercial pilots and professional scuba divers.19,26,37,38 Although some thoracic surgeons recommend surgery in patients with a first-time PSP if bullae are detected on CT scan,22 we think that this strategy is highly aggressive, unnecessary, and unproven; thus we do not incorporate this practice into our treatment strategies.

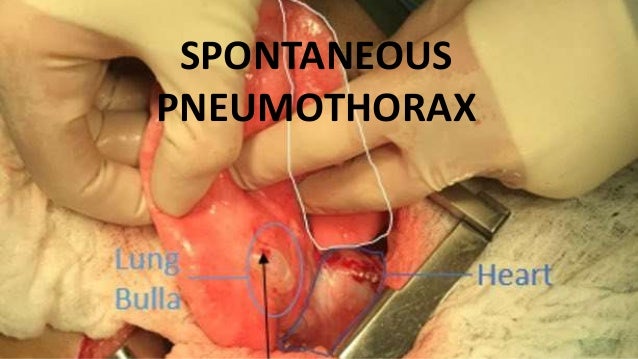

- 30. • VATS is the surgical procedure of choice for SP, replacing the previous procedure, axillary thoracotomy.44,45 The goals of surgery are resection of the offending bulla, complete lung expansion, and pleurodesis to prevent recurrence. A standard three-port VATS technique is used with lung isolation through a double-lumen endotracheal tube. The entire lung is carefully inspected, with particular attention to the apex and superior segments, because these are typical bullae locations. Saline flooding of the hemithorax during gentle lung inflation can help locate a ruptured bleb. Some surgeons resect the apex of the lung even if no bleb is located, although our practice is to perform lung resection only when a bleb is identified (Fig. 27-1). Buttressed staple lines are not necessary with otherwise normal lung parenchyma

- 31. •

- 32. •

- 33. • Intraoperative pleurodesis should be performed in addition to blebectomy. Mechanical pleurodesis is our most common method and is performed with use of a Bovie scratch pad with aggressive abrasion of the parietal pleura (Fig. 27-2). It is our practice to infuse doxycycline as an additional chemical sclerosant, although some surgeons choose to infuse talc at the time of surgery with good results and minimal impairment of pulmonary function over time.46,47 This is in spite of a recent study out of Korea suggesting that there is no difference in recurrence with mechanical pleurodesis following bleb resection

- 34. •

- 35. • Another effective method of obtaining pleural symphysis is parietal pleurectomy, by either VATS or open techniques. Results are similar to those of mechanical abrasion.49,50 Surgeons should make every effort to control air leak before leaving the operating room. Apical chest tube placement is crucial to full lung expansion. Postoperatively, chest tubes are placed to water seal as soon as a chest x-ray demonstrates full expansion, and no air leak is present. VATS successfully resolves SP and prevents recurrence in more than 90% of patients.51 Whereas some studies show that recurrence of SP is slightly higher with VATS compared with thoracotomy, this small increment does not justify the discomfort and lost work days in this generally young population.52 Thoracotomy is reserved for VATS failures and complex giant bleb resections not amenable to VATS.

- 36. • SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS Secondary Spontaneous Pneumothorax Clinical presentation of SSP is similar to that of PSP; however, dyspnea and respiratory compromise are often more profound, given the presence of underlying lung disease, even with small pneumothoraces. In this setting, intervention should be performed quickly with tube thoracostomy. Major causes of SSP are COPD with bleb rupture followed by Pneumocystis infection in patients with HIV infection, asthma, cystic fibrosis, necrotizing pneumonia, or tuberculosis. Less common causes are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, lung cancer, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, sarcoidosis, and catamenial pneumothorax.12 SP in patients with COPD portends poor long-term prognosis.53 Management strategies must be tailored to the individual patient. Operative risk in a markedly compromised patient must be weighed against the potential morbidity and prolonged hospital course that can accompany nonoperative intervention. We have found Heimlich valves particularly valuable in managing patients with prolonged air leak because they allow easy ambulation and outpatient management.

- 37. •

- 39. • Catamenial pneumothorax in a 40-year old woman. (a) Posteroanterior radiograph shows a right-sided pneumothorax (arrows). (b) Image obtained at video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery shows round brown endometrial implants (arrows) on the right hemidiaphragm.

- 40. •

- 41. •

- 42. • Conclusions: Catamenial pneumothorax may be suspected in ovulating women with spontaneous pneumothorax, even in the absence of symptoms associated with pelvic endometriosis. During video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, inspection of the dia- phragmatic surface is paramount. Plication of the involved area alone can be successful. In complicated cases, hormonal suppression therapy is a helpful adjunct.

- 43. •

- 44. •

- 45. • Patient 2 In December 2001, a healthy 32-year-old woman, gravida 0, had two right-sided spontaneous pneumothoraces and was treated with a medical talcum pleurodesis. During VATS after a second recurrence in May 2002, no lesions were found. We performed an apical pleurectomy down to the seventh rib. After another recurrence that coincided with her menses in August 2002, we discovered during reexploration several perforations in the centrum tendineum of the dia- phragm, associated with purple nodules. Through a minitho- racotomy, we excised a perforation with the adjacent nod- ule, reinforced the perforated portion with a double running suture, and performed a talcage. Histologic examination confirmed an endometrial implant (Figure 2). After release, she had a recurrence in October 2002. To explore the extent of a possible abdominal endometriosis, we undertook a rethoracoscopy in combination with laparoscopy. The in- trathoracic findings were inconclusive, although we did not mobilize the whole basal portion of the lung. Laparoscopic exploration confirmed the suspicion of disseminated pelvic endometriosis. After recovery, luteinizing hormone–releas- ing hormone analog therapy was started, and the patient has been symptom free for 17 months.

- 46. •

- 47. •

- 48. •

- 49. •

- 50. •

- 51. •

- 52. •

- 53. •

- 54. •