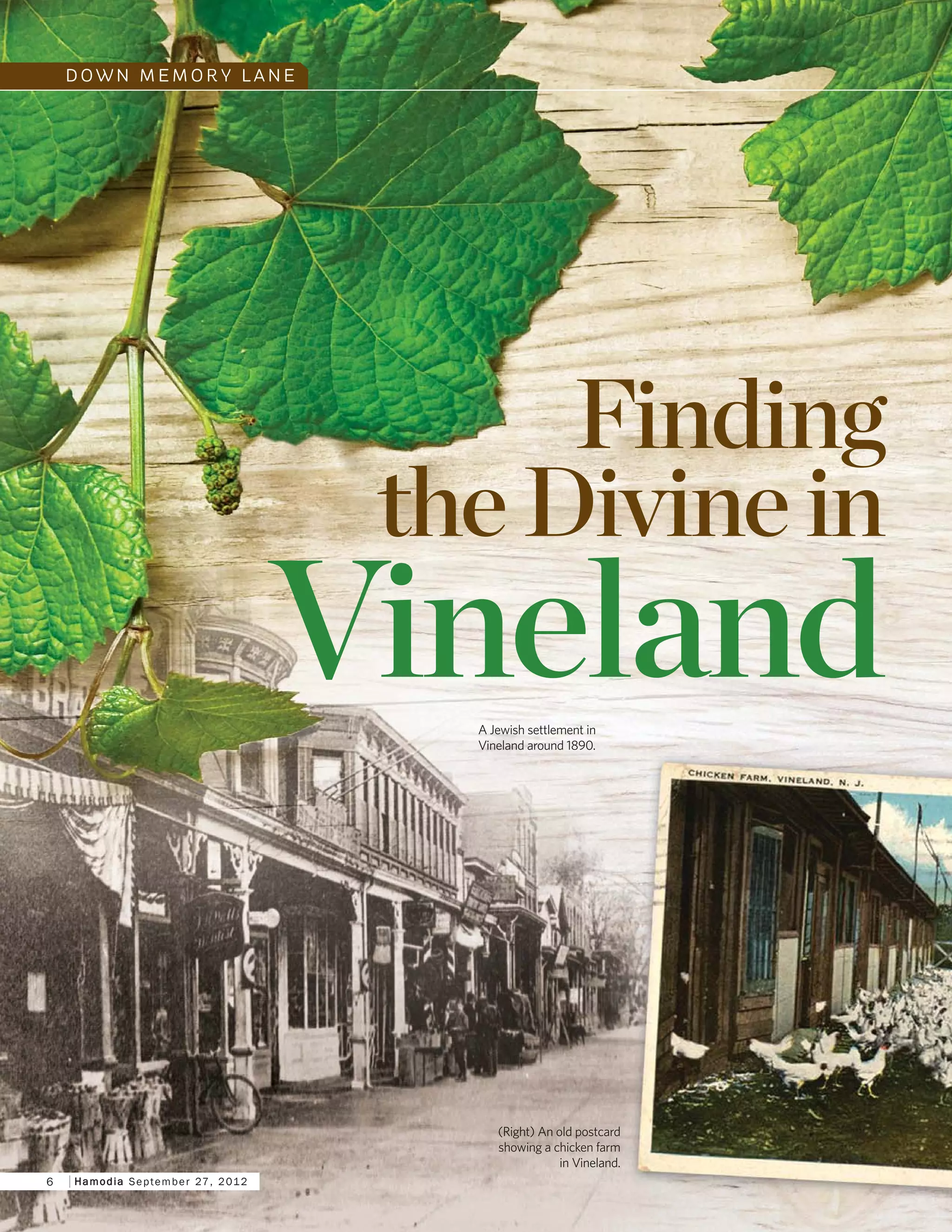

The document details the history of the Vineland Jewish settlement, established in the late 19th century, as a response to the plight of Eastern European Jews facing persecution. It discusses the various agricultural colonies and community developments initiated by figures like Baron de Hirsch, the struggles of immigrant families, and the eventual decline of traditional farming practices and Jewish identity over generations. Despite these challenges, the settlement evolved into a vibrant community with a rich cultural and religious heritage, though many descendants have faced assimilation and disconnection from Jewish traditions.

![IInnyyaann MMaaggaazziinnee 11 Tishrei 5773 9

cemetery, a chevrah kaddisha, and social

clubs. Because of the problem of techum

Shabbos, each town had its own shul,

but Jewish education did not receive the

same priority; hence the loss of later

generations to assimilation.

Several other towns were established

not far from Alliance and the Baron de

Hirsch towns. The best-known was

Woodbine because of its planned mix of

agriculture and industry. It was only

thirty miles from the earlier colonies,

and it was the first incorporated Jewish

borough in the United States. In 1893,

an agricultural school was set up for

the immigrant boys of

Woodbine, with courses in

English, farming, and the

trades. Ultimately the Jewish

agricultural town of

Woodbine failed, probably

due to its poor soil.

The Jewish colonies in

southern New Jersey were

part of what came to be

called the Am Olam movement — or, by

some historians, the back-to-the-soil

movement, which flourished well into

the 1920s and ’30s. The towns listed

earlier lasted longer than Woodbine;

most of the colonists were poultry

farmers and raised blackberries,

strawberries, blueberries, and other

crops that suited the soil.

The second generation generally

stayed in the colonies, but the

generation after that began leaving.

Tilling the soil and raising poultry was

not an easy life, and the white-collar

professions attracted the grandchildren

of the original settlers. Some migrated

to the nearby community of Vineland,

where they entered various

businesses and professions.

Vineland, New Jersey

Founded by Charles K.

Landis in 1861 along the rail

line to Philadelphia, the town

was planned as a utopian

society in which Landis set the

rules. Each settler who bought

land from him had to commit

to building a home within a year,

farming a minimal amount of acreage,

and leaving space between the homes.

In Their Own Words

The following account was written

in 1932 by Sidney Bailey, one of

the early colonists of Alliance, in

honor of the fiftieth anniversary

of the colony’s founding. His

words reflect the motivation,

mindset, and priorities of its

founders — at the same time

indicating the stresses, dilemmas,

and changing values of Eastern

European Jews. The narrative also

indicates the roots of the colony’s

eventual failure to maintain

Jewish identity among the

residents’ descendants, even

though they had respect for

tradition. Without Torah values

and chinuch, without a strong

connection to the Source of their

success, the result of the “natural

life” was usually assimilation.

I

HAD THE PRIVILEGE of being one

of the three men … who

formulated in Odessa on Shabuoth

of 1881 the Am Olam idea that our

brethren should go to America to

become tillers of the soil and thus shake

off the accusation that they were mere

petty mercenaries, living upon the toil

of others. Our thought was to live in the

open instead of being “shut-ins” who

lived an artificial city life. … We came

here instead of going to Palestine, which

was then under a Turkish regime. Thus,

the exodus of 1882 began rolling en

masse to America, and Alliance was

established in May 1882…

Our wanderers, from various parts of

Russia, came with the purpose of

carrying out the idea of Am Olam — to

settle on land. Our people, being

Talmudists, merchants, and tradesmen,

knew nothing of the significance of

farm life. When they came to New York

and arrived at Castle Garden [the

immigration center before Ellis Island]

and talked very naively with our

Charles K. Landis

Continued on page 11

The Chevrah Kaddisha

chapel in Norma, NJ.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalvineland-150818165823-lva1-app6891/85/Finding-the-Divine-in-Vineland-4-320.jpg)

![IInnyyaann MMaaggaazziinnee 11 Tishrei 5773 11

The Heyday

In 1953, a Jewish day school was

established by the mostly German-Jewish

families in Vineland, including the

Loebensteins, the Mayerfelds, the

Blumenthals, the Frohlichs, and the

Weinbergs (later of Philadelphia, Toronto,

and Brooklyn). The Freimarks, a branch

of the Mayerfeld family, sent five girls to

Bais Yaakov High School in Williamsburg,

Brooklyn. They maintained an apartment

there for years as the girls attended school

one after another. The life span of the

Jewish day school in Vineland was short,

not even twenty years. After it closed, the

children were driven to Philadelphia by

older girls who attended the Jewish high

school there. Other parents sent their

children to public school.

Many well-known families were

Vineland residents for a time, among

them the Anisfelds and Zoltys of Toronto,

and the Bistritzkys of New York. Some of

these families built new lives as poultry

farmers in Vineland after surviving the

Holocaust. The community increased with

the arrival of a few Hungarian Jews after

the 1956 revolution, but not all were

observant.

During this postwar period, Rabbi

Moshe Eisemann of Lakewood, who was

of German extraction and a talmid

muvhak of Rav Aharon Kotler, zt"l, started

a yeshivah on the outskirts of Vineland

with about a dozen bachurim. It lasted a

few years and attracted some Washington

Heights students. The Eisemann family

had ten children, all of whom became

marbitzei Torah in various locales. One son

is Rabbi Osher Eisemann of Lakewood,

founder of the famous School for Children

of Hidden Intelligence (SCHI).

Many survivors in the Vineland area

were antagonistic toward Torah as a result

of their suffering during the war. Mrs. Effie

Mayerfeld, who was very active in the

community and conducted many

interviews with survivors for the Spielberg

Foundation, reports that the second- and

third-generation descendants of these

survivors did not stay connected to

Yiddishkeit. As a pillar of the community

for decades and the mother of kiruv

professionals, she attests to the fact that

several fourth-generation Vineland Jews

have returned to observance. Through her

forty-five years in Vineland and her

children’s activism, she has encountered

old folks and young, baalei teshuvah from

the world over, who cite their forebears’

roots in the Vineland area.

Yeshivah Shaarei Torah of Monsey,

New York, conducted a SEED program in

Vineland in the 1990s, during the summer

months. The fruits of that effort and

ongoing outreach have also brought

some progeny of Vineland residents back

to Torah.

German-American brethren who came

to meet us and help us, [the immigrants]

were warned against and advised to give

up the idea of becoming farmers, but

were advised to continue at their trades

or to become peddlers. Thus the Am

Olam broke up. However, a few

remained true to their ideals, and their

ambition was to be realized.

The group consisted of about one

hundred families, and it chose for

its delegates Moses Bayuk,

who was a successful

lawyer in the Russian

city of Bialystok, and

Eli Stavitsky to scout

the country for a

suitable site. This they

did and chose this

territory for one reason

only, that it was located on

the Jersey Central Railroad a little over

one hundred miles from the metropolis

of New York and about forty miles from

Philadelphia.

The vast stretch of land was parceled

out into fourteen-acre farms and

numbered. The streets were named in

honor of the trustees of the Alliance

Land Trust, Judge Isaacs, Eppinger,

Gershell, Henry, Simon Muir, Mendes,

and Jacob Schiff. The farms were chosen

by lot. Our next problem was to clear the

brush land for the homes and to build

the houses, consisting of one room and

garret, which was to “accommodate”

large families.

When berry-picking time arrived, our

men with their wives and children

started out early mornings and walked

for miles in search of farms requiring

pickers. Upon returning, the men would

go to the swamps to cut firewood or

break off limbs of trees and carry them

home upon their shoulders. The women

wouldcook,bake,washtheclothing,and

do other housework. A few of the men

worked in a brickyard in Vineland. ... To

keep the settlers out of “mischief” and to

Continued from page 9

Continued on page 13

Moses Bayuk

Danny Freimark, son of Reverend Ludwig, in front of his home on Plum Street in Vineland.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalvineland-150818165823-lva1-app6891/85/Finding-the-Divine-in-Vineland-6-320.jpg)

![the Mayerfelds and Loebensteins keep

Vineland’s name circulating in the

Jewish world, but of Norma, Alliance,

Brotmanville, Rosenhayn, and the other

original agricultural colonies there is

almost no Jewish remnant other than in

the cemeteries. As Effie Mayerfeld says,

the Baron de Hirsch Fund provided for

the economic and physical needs of the

Jews fleeing czarist Russia, creating shuls,

cemeteries, and mikva’os, but their

spiritual needs were not addressed.

DIFFERENT FROM THE OTHER SETTLERS were members of the

Mayerfeld clan, who settled settled first in Vineland and later in

Norma. Stemming from the town of Crumstadt near Frankfurt-

am-Main, Manfred was the first to arrive in the 1920s as a single

young man. He brought over his paernts, Uri Shraga and his wife,

and his brothers, Max and Sali, and his two sisters, who thus

escaped the churban in Europe. Each came with spouses and in-

laws, thanks to Manfred’s efforts. At first some of them settled in

Sag Harbor, Long Island, where one sister’s husband, Reverend

Ludwig Freimark, worked as a shochet and Jewish religious

functionary. By the 1940s they had all made their way to

Vineland.

The ability to keep Shabbos was what drew the

whole family to southern New Jersey. Nonreligious

relatives told them that they would not be able to keep

Shabbos in the United States even if they tried to

restart their previous businesses. Sali summed up the

family’s attitude: “The chickens won’t mind if I keep

Shabbos. The hens won’t care if I speak German.”

The Mayerfeld family members worked very hard at

poultry farming but didn’t talk about the hardships. They just

worked. There were no vacations, no visiting with other frum

families in their six-and-a-half-day-a-week schedule. As soon as

Havdalah was over, they went out to the chicken coops and worked

some more. The Shacharis schedule was adjusted according to the

time of year, sometimes before morning egg collection and

sometimes after. They also ran a boarding house to bring in some

extra income.

“All the fun was in our house. We didn’t know what we were

missing,” says Nechama Mayerfeld Katz, Sali’s youngest child, who

now lives in Far Rockaway. “When myparents scraped together the

money to send me to Camp Bais Yaakov for three weeks at age ten,

I was enthralled. A whole roomful of frum girls were bentching! It

was amazing to me [since I had] rarely met other frum girls.”

Manfred, Max, Sali, and their parents were mainstays of the

community, in Vineland and later in Norma. They opened the

Jewish day school with others, established the gemilus chessed

fund, which helped many immigrants get started, and they

ran the chevrah kadisha. Opa Sali Mayerfeld was the first

in their area to put an extension phone in his bedroom;

as president of the chevrah kaddisha, he didn’t want

anyone who called during the night to be unable to get

through to the chevrah. The Mayerfeld name is still

closely connected with Vineland even though only

Henry and his wife remain. The Mayerfelds gave up the

poultry business in 1978 and are now in construction and

building supplies.

The family has stayed connected to K’hal Adath

Jeshurun in Washington Heights and their German-Jewish roots.

Harav Shimon Schwab, zt”l, used to travel to New Jersey to

officiate at family simchos. Mrs. Helen Heidingsfeld Mayerfeld had

beenaclassmateoftheRav’sintheHirschRealschuleinFrankfurt.

The family members stayed connected to one another; the next

generations who married outside of Vineland returned regularly

and made sure that the second and third cousins stayed close. All

of the family members, who live around the world, are frum today,

many working as klei kodesh, kiruv professionals,

and lay leaders. Most of the Mayerfeld boys and

girls went away to yeshivos and schools out of town

since chinuch in town was erratic. Rabbi Uri

Mayerfeld, son of Manfred, is the Rosh Yeshivah in

Yeshivas Ner Israel of Toronto. Another Rabbi

Mayerfeld, Max’s grandson, is the rabbi of an

Persian congregation in Los Angeles. Rabbi Hershel

Newmark, whose wife is a Freimark, is a rabbi in

Brooklyn. Rabbi Eli Mayerfeld is the executive

director of Yeshiva Beth Yehudah in Detroit, and

his brother, Rabbi Moshe Mayerfeld, is one of the

directors of Aish HaTorah in London. These last

two are sons of Bernie, Sali’s son.

The Mayerfelds of Vineland

Reverend.

Ludwig Freimark

Sali Mayerfeld with his grandchildren, Moshe

and Yehoshua Mayerfeld, circa 1978.

HHaammooddiiaa September 27, 201214](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalvineland-150818165823-lva1-app6891/85/Finding-the-Divine-in-Vineland-9-320.jpg)

![IInnyyaann MMaaggaazziinnee 11 Tishrei 5773 15

Neither the fund nor the settlers made

provisions for the chinuch of the children,

and the descendants of the original

settlers were therefore largely lost to Klal

Yisrael.

There is one remaining descendant of

Alliance settlers in the vicinity who is

actually still farming the same land and

is shomer Shabbos. He has children and

grandchildren in Eretz Yisrael who are

also frum. His wife’s family, who were also

farmer colonists brought to till the land

through the Baron de Hirsch Fund at the

end of the nineteenth century, resettled in

Colchester, Connecticut. The fund

selected several New England locations

for colonization by Eastern European

Jews, but only few historical relics of these

failed Am Olam farming ventures remain.

Ninety miles from Lakewood, New

Jersey, America’s Torah capital, Jewish

visitors to the tri-city area of Millville,

Vineland, and Bridgeton come to visit the

Wheaton Glassworks company town,

now restored as a historic site. Some

make a detour to Vineland for a minyan if

they are well informed. Lakewooders

may go to Millville’s Wheaton Village on

Sundays and Chol Hamoed, but little do

they know that the sites of an early

Jewish agricultural experiment are

nearby in Cumberland County and in

Salem County. II

We are grateful to the Cumberland County Jewish

Federation for furnishing some photos for this feature.

Since it is impossible in a magazine feature to

mention every person, shul, and organization that

contributed to the uniqueness of any community, we

invite readers to share additional important

information via letters to the editor.

Torah, Mr. Krassenstein the Talmud,

and [lehavdil, my wife and I] the works

of Schiller and Goethe. ... We petitioned

the Board of Education for greater

school facilities, and in consequence

another school was built in Alliance. In

all, as many as five public schools were

built in our midst. ... We built four

synagogues … [and] inaugurated a

Sabbath school where my wife read

poems in Yiddish from Rosenfeld

and others, and also in German

from Schiller and Goethe, and I

spoke on Jewish current events and

Jewish post-biblical history and on

Jewish ethics generally, from the

Scriptures and the Talmud...

Now, after a lapse of fifty years

from such a meager beginning,

when many a rib was broken as we

ran into a stump while plowing or

cultivating; after learning how to

harness horses to a double plow and

to use tractors, hay loaders, potato

planters, and other farm

machinery, we may feel thankful

and satisfied with our achievement.

Our farms are all paid for, we have a

good name and credit in the bank,

befitting industrious and thrifty

people. We feel prosperous and can

keep our heads up; we are employed

steadily; we are our own bosses. We are

well and fairly comfortable and happy.

Even [the Depression], which played

such havoc in the cities with our

brethren who were gambling in real

estate and in stocks and bonds, didn’t

hurt us very much. We lost neither our

heads nor our homes. Indeed, we have

less temptations, albeit less luxuries.

We lead a natural life.

Continued from page 13

The Alliance cemetery

entranceway exhorts visitors

to remember its past.

(Inset) A stone engraving

lists the year of the Alliance

cemetery’s founding, 1891,

and the members of

its board.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/finalvineland-150818165823-lva1-app6891/85/Finding-the-Divine-in-Vineland-10-320.jpg)