Contents lists available at ScienceDirectChild Abuse & Neg

- 1. Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Child Abuse & Neglect journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/chiabuneg Research article Clout or doubt? Perspectives on an infant mental health service for young children placed in foster care due to abuse and neglect Fiona Turner-Hallidaya,⁎ , Gary Kaintha, Genevieve Young- Southwarda, Richard Cotmoreb, Nicholas Watsona, Lynn McMahona, Helen Minnisa a Institute of Health & Wellbeing, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK b NSPCC, London A R T I C L E I N F O Keywords: Infant mental health Decision-making Foster care Evidence Social work Child abuse/neglect A B S T R A C T

- 2. Despite knowledge about the profound effects of child abuse and neglect, we know little about how best to assess whether maltreated children should return home. The effectiveness of the New Orleans Intervention Model (NIM) is being tested in a randomized controlled trial where the comparison is social work ‘services as usual.’ The future trial results will tell us which approach produces the best outcomes for children; meanwhile qualitative process evaluation is generating intriguing findings about the perceived impact of NIM on decision-making about childrens’ fu- tures. Interviews and focus groups were conducted with social workers, foster carers, legal de- cision-makers and the NIM team (n = 63). Data were analysed thematically. Findings suggest that NIM is seen as bringing greater influence (‘clout’) to decision-making due to its depth of focus, provision of treatment for the family, health professional input and perceived objectivity. Simultaneously, the NIM approach and the detailed information it produces potentially throws judgments into doubt in the legal system. Clout/doubt perceptions permeate opinions about NIM and are inter-related with a historical discourse about ‘health versus social’ models of information gathering, with implications for assessment of child abuse and neglect that extend beyond the study context. The juxtaposition of ‘clout versus doubt’ both highlights and is strengthened by an intense focus among social workers and legal professionals on how evidence will be regarded within legal fora when making decisions about children. There is continuing uncertainty in the child welfare system about the best ways of assessing

- 3. maltreated children, underscoring a con- tinued need for the trial. 1. Introduction 1.1. The need for quality assessment in the complex world of child abuse and neglect Research continues to document the profound personal and societal costs of childhood abuse and neglect (e.g., Caspi et al., 2016; Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). We know that one of the key factors in establishing a child’s resilience to such effects is positive and emotionally responsive caregiving post- maltreatment (Dozier, Bick, & Bernard, 2011; Dozier, Zeanah, & Bernard, 2013). What is less well known, however, is how best we can make the complex decision about whether a child http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.012 Received 21 February 2017; Received in revised form 30 June 2017; Accepted 23 July 2017 ⁎ Corresponding author at: University of Glasgow, House 1, Room 311 (Academic CAMHS), 1 Horselethill Road, Glasgow G12 9LX (Twitter: ACE_centre2016). E-mail addresses: [email protected] (F. Turner-Halliday), [email protected] (G. Kainth), [email protected] (G. Young-Southward), [email protected] (R. Cotmore), [email protected] (N. Watson), [email protected] (L. McMahon), [email protected] (H. Minnis). Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184–195

- 4. Available online 17 August 2017 0145-2134/ © 2017 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. T http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/01452134 http://www.elsevier.com/locate/chiabuneg http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.012 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.012 mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] mailto:[email protected] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.012 http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1016/j.chiabu.2017 .07.012&domain=pdf should return home or not after they have been taken into care. Robust assessment is crucial if decisions are to be beneficial for the child, but there are many challenges in measuring mal- treatment and in disentangling cause from effect (Dinkler et al., 2017; Glass, Gajwani, & Turner-Halliday, 2016; Pritchett et al., 2016). Decision-makers know that there are potential pitfalls in either reunifying children with their parents or in deciding on permanence via long-term foster care or adoption. Half of maltreated children who return back home will be maltreated again within two years (Luke, Sinclair, Woolgar, & Sebba, 2014). This has to be balanced against the knowledge that, for young children under five, disruptions in their relationships with primary caregivers

- 5. can be particularly problematic (Dozier et al., 2013) and foster care can lack a focus on their specific needs (Zeanah, Shauffer, & Dozier, 2011). Ensuring the best outcomes for these chil dren necessitates a research spotlight on how to generate the best quality assessment information upon which to base the life-changing decision of reunification with their parents or permanence. 1.2. The introduction and testing of a new model of assessment In this paper we report on the introduction of a new multi - disciplinary infant mental health service for children aged 0–5 in Glasgow, Scotland, who have been placed in foster care due to concerns about abuse and/or neglect. This service is based on the New Orleans Intervention Model (NIM) (Minnis, Bryce, Phin, & Wilson, 2010; Turner-Halliday, Watson, & Minnis, 2016; Zeanah et al., 2001), which was developed by the Tulane University Infant Team and is made up of psychologists, social workers and a psychiatrist. NIM is being implemented internationally in the US, Australia and England. It has had some encouraging results in the US (Zeanah et al., 2001), however we still know little about its effectiveness. For the first time, NIM is being compared to social work ‘services as usual’ (SW-SAU) in a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) in Glasgow, Scotland (Minnis, 2016; Pritchett et al., 2013; Turner - Halliday et al., 2016). This means that all children who come into care due to suspected abuse and or/neglect, aged 0–5 in Glasgow, are randomized to NIM or SW-SAU and researchers at the

- 6. University of Glasgow measure child outcomes across three different time- points (baseline, 15 months and 2.5 years after the child has been placed in foster care). The trial (known as the Best Services Trial: BeST?) exemplifies the notorious challenges in carrying out RCTs of complex inter - ventions: the existence of multiple outcomes, multiple partners working across multiple settings and agencies, the interventions (both NIM and SW-SAU) comprising multiple elements and a need for flexibility and adaptability in the delivery of the programs (Craig et al., 2008). However, as in any large randomized controlled trial, we expect a good balance across the two groups with regards known and unknown factors (e.g., age, gender, family size) so that only the interventions should differ. NIM and SW-SAU represent different lenses of assessment, different professional skill mixes and different timescales. Both NIM and SW-SAU include a three- month assessment of the family, but the NIM intervention additionally includes a six to nine month trial of treatment that aims to improve family functioning, child mental health and maximize the family’s chance of having the child home, where in the child’s best interests. In Scotland, there is no legal timeframe for decision- making, unlike in England where placement decisions have to be made within a maximum of twenty-six weeks. NIM (called the Glasgow infant and family team – GIFT – in Glasgow) offers a detailed assessment of all of the child’s attachment

- 7. relationships using standardized measures followed, where possible, with the trial of treatment that uses interventions such as Circle of Security, Parent-Child Psychotherapy and Video Interaction Guidance (VIG) (Turner-Halliday et al., 2016). SW-SAU do not offer formal in-house treatment but do reflect on their naturalistic observations with parents and can refer parents onto external services, e.g., substance misuse counselling, if required. In the United Kingdom (UK), SW-SAU usually involves regular contact with families to assess their likelihood of having the child home. Because preventative social work is well developed in the UK, often this will entail thorough scrutiny of past social work involvement with the family and observation of the quality of child-parent contact. The aim of both services is to make a timely recommendation concerning the child’s future placement based on the perceived best outcome possible for the child, be this reunification with their birth family or adoption. Fundamentally, we do not yet know how a new multi- disciplinary infant mental health model will fare in the Scottish context in comparison with the long-standing expertise of traditional social work judgement. 1.3. Using process evaluation to explore the context of NIM The results of BeST? are due in 2021 when we will hopefully learn whether NIM or SW-SAU is the most cost-effective service, but in the meantime there is much to be learned about how an infant mental health model is perceived in the child welfare system

- 8. and, in particular, how the infant mental health mode of decision- making is perceived in comparison with decisions made by social workers. A realist process evaluation is embedded in the trial and allows us to track the ways in which perceptions of both NIM and SW- SAU in the system context are operating (Turner-Halliday et al., 2016). This is important because we know that contextual factors can moderate outcomes and that, rather than receiving interventions passively, participants interact with interventions in ways that are influenced by their subjective attitudes and beliefs as well as cultural norms. This means that those in the context may respond to an intervention in ways that cannot be predicted (Moore et al., 2014). Such subjective reaction, rather than lying dormant, can actively affect what happens in practice. The well known ‘placebo effect’ in trials (re-constructed as a ‘meaning response’ by Moerman and Jonas, 2002) is a classic example of perception affecting outcome. So too is the effect of differing subjective opinions on relationships; for example, conflicts between agencies in the child welfare system can cause delays for children and their families (Johnson & Cahn, 1995). The relationship between perception and practice, in the wider context of an intervention, is circular; Pawson and Tilley (2004, p. 5) remind us that “successful interventions can change the conditions that made them work in the first place.” In this paper, we unpack the views and understandings of those involved in, or affected by, NIM’s implementation – especially F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184–

- 9. 195 185 their views on its impact on decision-making in the child welfare system. Using inductive qualitative methodology, the process evaluation we report here has allowed us to move beyond the normal confines of the RCT, where the focus is very much on the success or otherwise of the intervention. By exploring the context of NIM, we aim to generate explanatory power to explain why NIM may, or may not be, effective in Glasgow. This is particularly important in a trial of a complex intervention where – following an iterative process – the contextual and perceptual impacts on both the intervention and control are captured as they happen; for example the evolving legal landscapes and changing perceptions of NIM as it embeds in the system. This study’s use of realist process evaluation embedded in an RCT is an example of a growing awareness of the necessity to integrate process and outcome data to maximize our ability to interpret results. This represents a movement beyond the historical discourse of ‘quantitative versus qualitative’ methods and beyond the preoccupation only with “does it work?” (Oakley, Strange, Bonell, Allen, & Stephenson, 2006). Process evaluation is providing insight into the contextual and systemic differences between the UK child welfare context and New Orleans (where NIM was

- 10. originally developed). These identified differences unders core that the RCT question of ‘which service is best in Glasgow?’ is a very genuine one. NIM in Glasgow may not generate the same apparently positive results as have been suggested in New Orleans because Glasgow may be dealing with fundamentally different families in a different system. Contextual differences between the two settings include the fact that New Orleans does not have the thorough preventative social services that we do in Scotland so that parents in Glasgow are more likely to have been involved in intervention efforts to prevent maltreatment in the first place. Consequently, the parent group who comes into NIM may have more entrenched problems and their children may have greater attachment insecurity due to going back and forth between their family and foster care. Glasgow does not have a system like New Orleans that legally endorses parents’ engagement in NIM, making it possible that Glasgow parents may have higher instances of non-engagement. Instead, Scotland has an internationally unique legal system for children – the Children’s Hearing System – a key pillar of which is the involvement of Children’s Panels of specifically trained lay people who make decisions about children in the child welfare system, although certain decisions (such as long-term orders for adoption or permanence) are still made by judges (Sheriffs) in the Sheriff Court. Unlike in the US and England, however, judges do not routinely impose timescales around children’s permanent placement decisions, leaving

- 11. uncertainty and interpretability over what are the most timely decisions for the child. Although the Children’s Hearing System has the Welfare Principle (where the welfare of the child should be of para- mount consideration) as its foundation, it has become more adversarial in recent years with increasing involvement of lawyers (Porter, Welch, & Mitchell, 2016). Our realist process evaluation is finding that parents receive varying advice from lawyers in relation to NIM with some being advised not to engage; an example of the increasing challenges for Children’s Panels in making decisions when faced with conflicting opinions (Walker, Wilson, & Minnis, 2013). Exploring such legal tensions will be a new focus for the process evaluation as the trial moves forward. Furthermore, there are differences between New Orleans and Glasgow in relation to the care system. In addition to a concern about instability in the Glasgow care system (Minnis et al., 2010), children in the UK routinely go into emergency and short-term foster care (a pathway that sometimes results in multiple placements) while decisions are made about their future. If it is decided that adoption is the most suitable outcome, the child will usually move to new adoptive parents. In New Orleans and many other parts of the US, foster carers are dually registered as prospective adopters so that, if a child cannot return home, their foster carer routinely becomes their adoptive parent (Turner-Halliday et al., 2016). This means that, for children who are not able to return home, NIM in

- 12. the US is able to work with the child’s long-term caregiver whereas there are challenges for NIM in Glasgow in not being able to work on long-term attachment relationships with such children. 1.4. Using process evaluation to explore the impacts of NIM on decision-making The introduction of NIM into the child welfare system marks the first time that an infant mental health model has been in- corporated into social work systems. The multiple challenges of multidisciplinary working in other fields have already been docu- mented (e.g., Robinson & Cottrell, 2005; Satterfield et al., 2009), but not previously in this context. Realist process evaluation allows us to explore this novel interaction between a health and social approach in assessing cases of maltreatment. It also heightens understanding about the way that NIM generates information upon which to base decision-making, and how the resulting in- formation is received in a child welfare system where there is a longstanding tradition of social work processes. We already know that health and social care differ in terms of their approaches to generating information upon which to base decision-making. Healthcare practitioners consider RCTs to be the gold standard research methodology. These – like BeST? – are predicated on a foundation of uncertainty about whether the intervention (NIM) or the control (SW-SAU) produces the most fa- vorable outcomes (Greiner & Matthews, 2016). The process of randomization to intervention or control in order to even out all known and unknown differences (confounders) between the two groups, except for the intervention that they receive, is fundamental

- 13. since it is the most robust way of preventing selection bias (Craig et al., 2008.) In health, there is a notable congrue nce between the way that medical assessments, for example, are performed and the way that an RCT gathers evidence: both have starting-points of uncertainty where the task is an inquisitive, bottom-up approach, to information gathering. This approach, followed by NIM, may be at odds with, and undermine, the values of social work where common sense representations and reflexive understanding of what is going on in a family are used to contextualize and locate work. In other words, social workers are much more likely to make use of their pro- fessional autonomy during data-gathering. Rather than a purely information-gathering approach to decision-making, it is argued that social workers are operating within a “limited rationality” that is curtailed within legal and organizational requirements (Webb, 2001, p. 57). The uptake of “evidence-based practice”, therefore, has varied across professions. Medicine has adopted evidence-based practice F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 186 into its culture in a way that public policy, for example, has not (Macintyre, Chalmers, Horton, & Smith, 2001). This can be

- 14. linked to varying values between professions in terms of what constitutes the nature of ‘evidence’ and the position of ‘certainty versus un- certainty’ in particular. For example, in the legal system, there is value placed on the professional expertise and autonomy of lawyers and judges in a way that also values an assumption of “certainty as to the ‘right’ answer” (Greiner & Matthews, 2016, p. 303). In contrast, in health, an ethical pre-requisite of RCTs is “equipoise,” defined as a “balance of forces or interests” (Oxford Dictionaries) – in other words, uncertainty as to the outcome of the study. 1.5. This paper – aims and objectives Whilst the BeST? trial continues, we seek to examine how NIM – and its style of decision-making – fits into Glasgow’s child welfare system by gathering qualitative data from a range of participants in our process evaluation (Turner-Halliday et al., 2016). This inductive analysis to date has unearthed a key overarching theme around the perceived impact of NIM on decision-making in the Scottish legal system. The theme represents an apparently contradictory position amongst participants about NIM’s abili ty to make effective decisions, with implications for decision-making and the nature of ‘evidence’ beyond the trial or the Scottish context. These views have permeated the qualitative data gathered from a range of participants throughout the course of the trial and indicate the value in identifying and unpacking unpredictable reactions to a new intervention in the system (Moore et al., 2014). In our

- 15. discussion of the data, we aim to contextualize this theme by linking it with the aforementioned theories of evidence-gathering in health/social models and by proposing what the findings means for the trial and the assessment of cases of abuse and neglect more generally. 2. Methods Data were collected as part of the qualitative process evaluation embedded in BeST,? which follows a realist evaluation approach (Pawson & Tilley, 2004) and uses an inductive qualitative analysis to explore NIM’s context. Realist evaluation asserts that pro- grammes are embedded in open social systems, which are active, and that can change and evolve. One of the key tasks for evaluation, therefore, is to unpack the complex social reality in the context of an intervention in order to understand how interventions function. Realism assumes that programmes will vary depending on context and what is contextually significant may not only relate to locality but also to systems of interpersonal and social relationships. It is proposed that certain contexts will be supportive to the programme theory and some will not, which necessitates a key task in sorting one from the other. As one aim of the larger task of conducting a realist evaluation over the course of the trial, this paper is focussed on NIM as embedded in a social system and, by collecting data from participants across the child welfare system, we aim to understand per-

- 16. ceptions in that context and the ways in which such thinking may be interacting with practice – with possible influences on outcomes. There is growing acceptance that, in the evaluation of complex interventions, evaluations need to understand this complexity to inform future intervention development, or the application of the same intervention in another setting (Craig et al., 2008). Qualitative work in the first part of the trial focused on the implementation and delivery of services from the perspectives of key stakeholders; social workers, foster carers, NIM and SW-SAU. The main data collection method for this purpose was focus group discussions, which were repeated throughout the trial in order to track changes and developments over time. The exception was data collection with foster carers; it was found that they preferred the more personal and private nature of an individual interview. The second phase of the process evaluation, although still tracking the development of issues gleaned in the first phase, adopted case study methodology to focus more specifically on the impact of NIM and SW-SAU on a selection of children and families enrolled in the trial. This narrower focus allowed a more in-depth investigation into the experiences of the birth family, foster carers, social workers and health professionals when a case of maltreatment is under assessment by NIM or SW-SAU. The primary methodology for this part of the process evaluation was individual interviews. For the aspect of the larger process evaluation that we focus on in this paper, we used interviews and focus groups with 63

- 17. participants falling into the categories of a) SW-SAU, b) NIM, c) Foster Carers, d) Children’s Hearing System: 19 interviews, and 11 focus groups. Interviews: 6 SW-SAU individual interviews, 5 NIM individual interviews, 8 foster carer individual interviews. Focus groups: 3 SW-SAU focus groups (11 participants) 5 NIM focus groups (12 participants), 3 Children’s Panel focus groups (26 parti- cipants). Whereas the NIM and SW-SAU focus groups were with the same teams over different time-points in the ongoing trial, the individual interviews with NIM and SW-SAU were with selected team members for conducting the case studies. The five participants in NIM individual interviews also took part in the NIM focus groups and so are not counted twice. Ethical approval was obtained from West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee. Sampling was purposive: all members of NIM and SW-SAU teams were invited to take part in the process evaluation based on their ability to provide views about the models being implemented. Similarly, social workers were invited to take part in focus groups if they were aligned to any of three local area teams representing the geographical spread of area team social work services across Glasgow. Panel members were purposively recruited from six sectors across Glasgow to provide views that represented the spread of panels across the city. The foster carers all had children being assessed by either NIM or SW-SAU at the time of data collection. For the case studies, sampling was both purposive and random; NIM and SW-SAU identified a number of cases where there were

- 18. indications, during the process of assessment, about the nature of the final recommendation and the process evaluation, then we randomly selected two cases from each service where it looked likely that there would be opposing outcomes; one case from each service where indications were suggestive of the child/ren being rehabilitated home, and one case from each service where it looked likely that a recommendation would be made for permanency. Participants were invited to take part in case study interviews based on their involvement in the case and their ability to provide a view on the child from their specific perspective; that is, from the angle of the F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 187 parent, the foster carer, the area team social worker and the key workers involved in the case from either NIM or SW-SAU. All participants received study information forms and had the opportunity to ask questions before consenting to take part. The focus groups and interviews used topic guides that evolved iteratively from thematic analysis during the process of stake- holder engagement prior to the start of the trial and continue to develop as the trial unearths key issues as it progresses. Interview and focus group topic guides were semi-structured so that pre- defined issues were explored whilst allowing for new issues and topics to emerge as introduced by the participants. The general focus of

- 19. all interviews and focus groups was the introduction of NIM into the system. Interviews and focus groups lasted approximately sixty minutes and were audio recorded then transcribed verbatim. All data was stored securely and confidentially and participants were anonymized for the purpose of reporting. A thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was employed where each transcript was examined in detail, noting reflections and preliminary themes. Transcripts were read numerous times to identify repeating patterns and/or differences between transcripts, and any new themes identified at this stage were noted. Lists of identified themes were then organized: themes that were found to relate to each other were clustered together and became a group of themes divided into sub-themes with an overall theme heading that captured the essence of each category. In this first round of analysis, FT-H identified that many of the categories of themes linked to a key overarching premise running throughout the data about the impact and influence of NIM on decision-making. This prompted the formulation of a research question about NIM’s influence and impact on decision-making in comparison with SW-SAU. With this more specific research question in mind, it was decided to conduct a second round of analysis through the lens of the emerging overarching theme. In order to enhance reliability of the analysis, this second round involved a second researcher (GY-S) who independently analyzed the data. Analyzes were compared

- 20. and an overall level of agreement between researchers was found, with the exception of each researcher identifying a few different minor sub-themes that were later identified by both researchers to be out-with the realm of the research question. These were omitted from the overall frame of themes for the paper so that the final themes were aligned only with the research question. 3. Findings The overarching theme identified in the primary analysis of the data was that which we have termed as ‘clout/doubt;’ a phrase representing a set of conflicting views about the impact of the evidence that NIM generates in cases of abuse and neglect. ‘Clout’ (influence or power) refers to the view that the information produced by NIM is held in higher esteem than that which is generated from SW-SAU. On the other hand, ‘doubt’ refers to the view that the NIM approach, and the evidence it produces, has the potential to throw into question (create uncertainty around) assessment services’ recommendations about a child when that recommendation is viewed by the legal system. In the second round of analysis (the more specific focus on clout/doubt), the theme was found to be multi-faceted and, although we later explain that clout and doubt are essentially ‘two sides of the same coin,’ the clout/doubt themes and their sub-themes are presented separately for the purposes of reporting: 3.1. The clout of mental health assessment

- 21. The ethos of a mental health focus when assessing wellbeing in maltreated children was largely seen as positive and it was this that made some feel that the model may better meet the needs of both children and parents. However, there was a stronger focus amongst SW-SAU and Children’s Panel members on the impact of NIM’s evidence in the legal system than on the model itself. One strand of this perceived impact was that NIM was perceived to have greater influence (clout) than SW-SAU. Three main themes were interpreted from the data as being pivotal in relation to perceptions of NIM’s clout: 3.1.1 NIM’s health professional input and position in the system; 3.1.2 NIM having an in-depth assessment focus; 3.1.3 The information gleaned from giving parents a trial of treatment. 3.1.1. NIM’s health professional input and position in the system NIM reports were perceived to be more influential than those from SW-SAU due to a combined effect of the type of professionals involved in the service and where NIM sits in the system comparative to SW-SAU. The presence of psychologists and psychiatrists when presenting NIM evidence was perceived by SW-SAU as adding an element of clout to judgment and opinion. SW-SAU reported that the Children’s Panel, in particular, saw health professionals as providing an additional level of expertise, which often strengthened SW- SAU’s recommendation:

- 22. “The fact that a child psychotherapist was sitting there [at the Children’s Panel] saying the same thing about contact that I was saying…I wouldn’t have just won it on my own, but because a child psychotherapist from GIFT [NIM] was there, saying the same thing, it was a done- deal then” (Area team 2 social worker). Mental health professionals were perceived to bring with them a “medical model,” which is thought by SW-SAU to hold particular credibility with the Children’s Panel: “[NIM] seems more like a medical model almost, and panels respond much better to medical models and they tend to trust doctors and psychiatrists and psychologists. They don’t tend to trust social workers and people who aren’t, you know, medically trained” (Area team social worker, case study 3). F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 188 Coupled with the perceived credibility of the team, NIM was repeatedly referred to as “external” to SW-SAU, particularly by SW- SAU and panel members. Whereas SW-SAU were seen as having a past relationship with the family (often being responsible for removing the child/ren from home as well as assessing them)

- 23. NIM was seen as having a more objective and fresh perspective of the case: “I think that the reports carry a lot of weight, especially if you are presenting that as part of an evidence to panels, because panels − whether we like it or not − sometimes maybe think that the social work or area team are not as objective, but they see them [NIM] as being external…and not just based on social work bias” (Area team 1 social worker). The combination of NIM’s perceived objectivity and level of expertise appeared to ease decision-making by panels: “[NIM] come in independently … it is uncomplicated that these people, who are experts, have come in and their recommendation is such and such, and you would put a lot of weight on that” (Children’s Panel member). The trade-off of NIM’s professional clout for SW-SAU, however, was that their own professional credibility could feel undermined: “I think we believe we should have more professional credibility than we sometimes have. I think probably people have got an anxiety that if we disagree with the GIFT [NIM] assessment and then you get two conflicting assessments going to family court, our assessment will be seen as the lesser…I don’t know whether that has happened, but I think it would be interesting to see if that happened” (Area team 1 social worker).

- 24. This resulted in a perspective that – inadvertently – SW-SAU may enhance NIM’s clout by translating their own feelings of comparative inferiority into the wider system. Some social workers therefore voiced a need for more displays of confidence amongst SW-SAU when presenting evidence in the legal system. 3.1.2. NIM’s in-depth assessment focus A mental health lens was seen as providing a more detailed assessment of need, thereby enhancing NIM’s clout. In one case study, SW-SAU felt that NIM had identified a child’s developmental issues that may otherwise have been missed: “When you do have a case like that with a child who has got additional needs, things can be masked, like her development. GIFT [NIM] had picked up on the clinical side of it, which has given us a much better and thorough assessment” (Area team social worker, case study 4). NIM’s detailed assessment information about a case appeared to further aid panels’ decision-making. The detail was seen as “scientific” evidence, particularly in relation to decisions about the frequency of contact sessions between children and their birth parent/s: “To have a scientific basis upon which to consider the difference between having contact twice a year and six times a year would surely be very, very helpful…I am quite frustrated that social work maybe say that they want to make less contact because it is not going

- 25. very well… and you say, well that’s not really enough information, what do you mean by ‘it’s not going very well?’ But on that [NIM] case there was a whole list of things” (Children’s Panel member). NIM assessments were also seen as more detailed in relation to information about parents. Although SW-SAU assessments were viewed to take account of parents’ history and own experiences of maltreatment, NIM was seen as better examining the implications of a parent’s past trauma on current functioning: “It [NIM’s assessment report] is very detailed and really goes into the case history in terms of the trauma for mum and dad and picking up on things that maybe perhaps in our own integrated assessments have just been skimmed over…but they have had the opportunity to really unpick that and work out why the parents are functioning the way they are now, as opposed to just all the historical stuff all the time” (Area team 1 social worker). Again, however, the perceived clout of NIM’s assessments had a counter point in that it can make SW-SAU feel that their pro- fessional expertise is being called into question: “I feel as if we are undermined at times because we are trained social workers, our job is to assess…social workers are skilled to assess, they do have the skills to do that, and they can come to some kind of judgment” (Area team 2 social worker). 3.1.3. A trial of treatment NIM‘s treatment component offers interventions that focus on

- 26. the parent–child relationship. These interventions can have a secondary effect of addressing difficulties for parents that relate to their own experiences of being parented. This is contrasted with SW-SAU where parents would usually be referred to external services (if available) for such interventions. While carrying out treatment takes longer, it aims to improve the accuracy of the recommendation made at the end by maximizing the parent’s chances of changing whilst demonstrating clarity in relation to any lack of change: “If we get to the point where we say that we would not recommend this child to go home, we have done it having had, you know, the best possible assessment, the best possible intervention. And in the end we have to work in the best interest of the child - on that really sound foundation of what we know and what we have tried to do” (NIM team member). F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 189 Improving accuracy was essentially seen as making the best decisions about the child in the long-term. For children who return to their parents, there was a view that undergoing treatment will make it less likely that they will end up coming back into care: “There are some cases where there would probably be that

- 27. process where the child might have returned home, but potentially would have come back into care without the right support, and that feels like a real strength of what we are doing” (NIM team member). For children who cannot be returned home, the evidence generated from the treatment phase was felt to add clout to the recommendation being proposed, even although the lengthier timescale of the process is often seen as a caveat: “People who have gone through the [NIM] process though by the end of it are saying ‘well actually it is worth it’ because the evidence is there in terms of parent incapacity… I think people get very frustrated with the timescale, you know, and there is no getting away from that” (Area team social work service manager). Those who saw the treatment phase as adding clout to decision- making generally saw the lengthier timescale as necessary payment for improved accuracy. A view of there being ‘differential suitability’ for the NIM model, however, was unearthed and this depended upon whether the case warranted a lengthier timescale. For foster carers, treatment (and a lengthier time to make a recommendation) was particularly suited to cases where previous reunification had subsequently resulted in the child/ren coming back into care: “I do not want these children to go back to their parents if it is not done properly because these kids were in care before and went back to their mum and dad and they failed within six months…I am not saying that I don’t want them to go back to their mum and dad, I

- 28. don’t mean that, but what I mean is they need to be spot on this time and I feel that this long assessment, because it is like a three- month assessment and then a further six months, is the right road for this family” (Foster carer F2). For other children, however, the treatment phase and lengthier timescale was not perceived to be warranted – this is where views of doubt become visible, which are now outlined in the following section. 3.2. The doubt created by a mental health approach The ‘flip side’ of NIM generating evidence that is perceived as more influential is that it was seen as having the potential to throw into doubt the claims and recommendations made after assessment. In our data, doubt perceptions were isolated to cases where it was perceived that a child should not return to the care of their parents. In such cases, fears were expressed that the mental health element of NIM would reflect more favorably on parents than a SW- SAU assessment because: a) it involves a more intricate assessment of child-parent interaction that can be open to interpretation and legal challenge; b) it has a current focus on family functioning that may miss wider information about the child’s social context that SW-SAU often glean; c) it offers parents a trial of treatment, which may convey a perspective that change is possible in families where SW-SAU believe it is highly unlikely.

- 29. These views are explicated in three sub-themes: 3.2.1 The intricate focus on child-parent interaction; 3.2.2 NIM’s lack of historical relationship with the family; 3.2.3 NIM’s trial of treatment. 3.2.1. The intricate focus on child-parent interaction The detailed focus on intricate child-parent interactions that NIM typically assess was thought by SW-SAU to reflect more fa- vorably on parenting capacity than their more naturalistic observation of the relationship. The difference in focus was seen as “psychological versus practical:’ “I think because there are health professionals there at GIFT [NIM], they certainly assess it in a much more thorough way I would say….no “thorough” is not the right word…they go into the ‘nitty gritty’ a bit more…they video it, they analyze very small snippets of contact, for example. If they see one thing positive − like very good eye contact where there was maybe issues with attachment − they would say ‘well we might have something to work with there.’ So they would assess it or they would judge it in a slightly different way whereas social work are looking through two-way mirrors and they are just looking generally at the contact and whether mum does have the capacity to meet the child’s needs; for example, can mum change a nappy when the child’s nappy needs to be changed? Does she recognize that? Is she able to stimulate them by getting the right toys? Able to feed them? You know, the practicalities rather than going into some of the psychological… I

- 30. think you can look at that more optimistically rather than just looking at the way that a social work would assess it” (Area team social worker). In cases where SW-SAU felt that reunification should not be recommended, they feared that the intricate-level data produced by NIM could also reflect an unrealistically positive view of parents in the legal system by providing more room for interpretation and challenge by family lawyers: “It [intricate-level evidence] lends weight but it also gives them [family lawyers] more things to challenge” (Area team social worker). 3.2.2. A lack of historical relationship with the family There is also a feeling that NIM can miss both a historical and a wider social context about the child. In many cases, SW-SAU has a long history of working with the children and the families concerned and there is a fear that NIM may miss much of the arcane F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 190 knowledge that social work has acquired. Social workers saw NIM’s focus as being primarily on current functioning as sometimes

- 31. presenting a more favorable picture of parental capacity: “I think it is different because we [SW-SAU] are not just doing the contact assessment…we are assessing the kind of dynamics in the house, and all the stuff that is provided in that…we are looking usually before they are removed so it is home environment that we are assessing rather than just the contact once the kids have been removed” (Area team 2 social worker). NIM’s focus on current functioning was sometimes seen as presenting an unrealistically positive picture of parenting capacity that would not be maintained. Some social workers feared that this focus would create doubt in the legal system over parental incapacity, resulting in children being sent home to parents who would be unable to maintain behavior change: “I am not saying they [NIM] are unrealistic, and they will still say what the concerns are as well, but I am thinking that this is all a bit artificial…mum and dad are doing okay just now, but, you know, that certainly wasn’t my experience, for example, when I had the children registered for a year…and weekly visits and everything, but now… they are able to pull some of that together, and my anxiety is that once the assessment phase is over, and if that child is returned home, that things would revert back to the previous behaviors” (Area team 1 social worker). 3.2.3. NIM’s trial of treatment Two angles of this theme were identified in the data:

- 32. 3.2.3.1 That NIM’s treatment phase makes it appear that some parents were given a chance when SW-SAU reportedly knew from the outset that reunification was not possible: 3.2.3.2 That a lack of synchronicity between the NIM timescales and those in the wider system can render NIM evidence as more ‘doubtful’ than it would have been if there had been a better fit. These two angles are now described: 3.2.3.1. Conveying a false possibility of change. SW-SAU held the view that there are certain families where it is clear early on – and often based on a historical perspective – that the parents are highly unlikely to ever achieve a level of sufficient parenting. NIM’s implementation of the treatment phase in such cases, where NIM later recommends non-reunification, is seen as a superfluous consideration of an unachievable outcome: “It’s commonplace for social workers, and particularly social work managers, to say to us ‘we wouldn’t be doing this [continuing to work with the family] if you [NIM] weren’t involved - there would be no talk of these children going home’ - and that’s the commonest difference” (NIM worker, case study 4). Implementation and/or continuation of treatment are perceived to weaken the case, legally, for non-reunification; that is, the treatment approach is felt to create doubt by conveying a sense of optimism that the parents could provide adequate care with the right intervention:

- 33. “It was quite clear, to me, that there should have been no rehabilitation plan from the evidence that was there, but certainly GIFT [NIM] were reluctant to make that decision at that time because they were saying they hadn’t gone through the whole assessment. There was support after support went on…there wasn’t any evidence of change at that point and I just felt that we were flogging a dead horse, you know, and giving some false hope to mum as well…and if you go to court with that it puts doubts in people’s mind that maybe mum can come through this and maybe she can parent her child or her children. So, I just think that kind of thing needs to be teased out a bit… certainly when there are cases were it does appear obvious that the children shouldn’t go back home at an early stage” (Area team 2 social worker). Again, a view of there being a differential suitability for NIM was apparent, with these apparently clearer-cut cases viewed as less aligned with NIM than those where decision-making takes longer. In this perspective, perceived early and clear indicators of non- reunification (only one example was given: repeated and failed previous attempts to improve parenting capacity) remove a need for improving the accuracy of decision-making through a trial of treatment. This contradicts NIM’s position where decision- making based on “early” indicators without thorough assessment is questioned, as is ascertaining the clarity of such indicators without a trial of

- 34. treatment. NIM aims to give parents a chance to change in response to treatment, where it is in the child’s interest and where parents can meet the conditions of treatment (e.g. attend regular appointments.) SW-SAU did not refer to NIM’s treatment phase also being based on a rationale that parents whose children cannot safely go home at the end of NIM treatment are less likely to maltreat children from subsequent pregnancies. Due to the stage of the trial, we do not yet know whether NIM is more likely than SW- SAU to recommend reunification, nor whether the trial of treatment has an effect on reunification rates. 3.2.3.2. The doubt over undefined timescales. The debate over whether NIM should be implementing or continuing treatment is often based upon a central question about ‘how long is enough?’ when it comes to giving parents opportunity to change. Not having an imposed legal timeframe in Scotland, even although court- imposed timescales lack an evidence-base, means that appropriate timescales – and whether parents will continue to change in this timescale − is open to interpretation. From the perspective of SW- SAU, parents demonstrating progress in treatment, but taking too long to reach a “good enough” level of care, introduces doubt over a later recommendation of non-reunification: “At the end of the NIM process, they [NIM] had said that mum was now at the place where we would have wanted her to be, like a few F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195

- 35. 191 months ago, but I think that inevitably leads to the question then why not give her a few more months then and see? Well she is at a place now where she has moved, but not enough to send the children home, so it leads to the legal argument of ‘give her more time”' (Area team 2 social worker). The need to make decisions in a timescale that is right for the child was discussed within all avenues of the data, with SW- SAU seeing NIM as sometimes lengthening the process beyond an optimal time-point and NIM pointing to delays in the wider system as creating the most barriers to a timely process. A lack of a legal framework that supports congruence between the timeline of NIM and processes in the wider system was seen as sometimes diluting the clout of NIM reports; for example, a delay between NIM making a recommendation in their final report and a Children’s Hearing being arranged. In such cases, doubt over whether NIM information was still relevant sometimes replaced former clout: “When I was on the hearing I was still thinking ‘but that [NIM report] was in June and things had moved on’ and so I felt that I couldn’t put the same weight on it and I felt very guilty about that because I felt all the work had been put in [by NIM]” (Children’s Panel member).

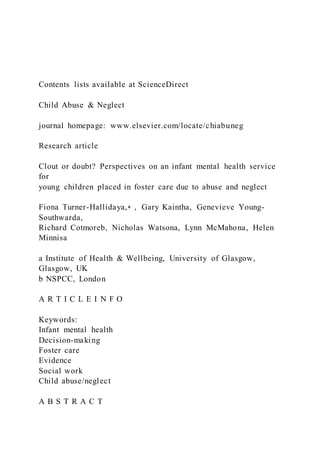

- 36. 4. Discussion 4.1. Overview of clout/doubt and relation to study aims The teasing apart of clout and doubt perceptions in the child welfare system leads us to conceptualize the theme as a two- sided, but inter-related, concept – a ‘double-edged sword’ – with neither clout or doubt existing as separate entities. Fig. 1 diagrammatically represents the perception that NIM is seen as having more clout in the system yet, in contrast, it is also seen to generate evidence that can be doubted. On the other hand, SW-SAU is seen as having less clout but perceptions are that their assessment information is also less likely to evoke doubt. There are clear dilemmas for assessors trying to generate evidence that will be heard, yet perceiving that the trade-off may be an increased risk of legal contest and the chance that their recommendation is not upheld. These are challenging positions for those who face the complex task of making recommendations about child welfare in the context of abuse and neglect. Ironically NIM’s ‘clout factors’ (its involvement of health professionals, perceived objectivity, depth of focus and its trial of treatment) are the very same aspects of NIM that are seen as having the potential to evoke doubt. Firstly, the health professionals in the NIM team, although being a key source of clout, were perceived by SW-SAU to lack a wider social and historical picture of

- 37. maltreatment. Rather than this being specifically about their health professional expertise (as is the case with clout), the doubt generated by health professionals was about their alignment with a current-day approach to assessment. The flipside of NIM’s proposed objectivity is a perceived inflation of some parents’ abilities in an unrealistic way by overlooking past history. NIM’s depth of assessment focus and resulting intricate-level evidence is seen as being open to challenge in the legal system in a way that SW-SAU evidence is less likely to be. Lastly, the trial of treatment for some parents, as well as being seen as having the potential to improving accuracy of decision-making, is thought to convey a message to the legal system that change is possible in cases where SW-SAU felt that it was clear at an early stage that reunification was unachievable. This message is seen as a factor that will lead to legal contest if, after treatment, a recommendation is made that the child should not go home. In research terms, clout/doubt suggests that the BeST? trial maintains equipoise. More broadly, our findings evidence genuine uncertainty in the child welfare system about the best way of assessing cases of child maltreatment: should assessment measure intricate-level interactions through a mental health lens or a more general, and perhaps a more contextualized, overview of the parents’ ability to respond to a child’s needs? Should it have a current or historical focus and should this focus be on the child, the

- 38. parents or the relationship? Should there be a treatment component implicating a lengthier timescale or a shorter timescale with no formal and routine treatment? Until we know the results of BeST,? these questions remain unanswered in terms of the impact of NIM and SW-SAU on child mental health. It is clear that the perceived answers to such questions, however, are inextricably linked with the notion of evidence impact and not just evidence quality. In other words, there is a driving focus on generating evidence that is most likely to be heard and NIM – high clout, high doubt SW-SAU – low clout, low doubt The ideal – high clout, low doubt Fig. 1. The relative impact of NIM versus SW-SAU evidence. F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 192 to withstand legal contest. However, according to our data, this ideal (see Fig. 1) appears unachievable because the assessment approach that leads to being heard (having clout) in the system

- 39. is perceived to simultaneously increase the likelihood of legal contest (doubt) about the resulting recommendation. 4.2. The context and creation of clout/doubt: an adversarial legal system Clout/doubt perceptions appear to be born out of an adversaria l legal context in which child welfare assessors and decision- makers are immersed. Participants in SW-SAU and the Hearing System answered open questions about the general impact of NIM with a central (and more specific) focus on how the new model will be viewed legally, suggesting that consciousness about how recommendations might play out in the legal system is highly influential. This leads to questions about whether an increasingly adversarial legal consciousness surrounding cases of abuse and neglect is shaping the assessment of maltreated young children as assessors attempt to pre-judge the ways in which the legal system will react to the evidence that they present. Whether this jeo- pardizes assessment that should be driven more straightforwardly by the needs of the child is a resulting and concerning question. Whereas clout appears to resonate with a general known difference between the power and influence of health versus social models (e.g. Robinson & Cottrell, 2005), the doubt theme encapsulates findings that shed a particular and novel light on the legal context of maltreatment. There is an irony in NIM attempting to enhance the quality of assessment evidence by providing depth of

- 40. focus and a trial of treatment, yet (according to SW-SAU) it is these very aspects that may lead to the potential for NIM re- commendations about a child not being upheld in legal contest. The immersion of clout/doubt in presumptions about NIM’s legal impact underscores the influence of context on perception. It is clear that perceptions about NIM construct it in a way that often contradicts the way in which it was originally conceived. For example, NIM was referred to as a “medical model,” whereas it is multi-disciplinary with professionals from a social work background making up half of the team. In addition, the health professional mix is dominated by those who would not be classed as “medical,” such as psychologists. Similarly, NIM was cited as being “external,” whereas the NIM team sees itself as being embedded within the child welfare system. Perceptions of NIM as “medical” and “external” are potential barriers to its integration into social work systems – an example of how perception of a model can impact on the actual relations between agencies. Yet these potential barriers are those features of NIM to which clout is attributed. NIM’s clout looks at least partly constructed on the basis of widely held traditional beliefs about the relative power of a mental health “medical” model in the ‘health versus social’ dichoto my (Beresford, 2002). It is possible that, in this context where there is an emphasis on legally impactful evidence, the health/social dichotomy becomes more visible. In other words, when the child welfare system is looking for evidence that has clout in the legal system, the traditional power and

- 41. influence attributed to health models fits this aim. In turn, the perceived power difference between health and social care becomes reinforced. 4.3. Decision-making timescales: clout/doubt and ‘certainty versus uncertainty’ SW-SAU in this study convey a sense that they are able to establish the right decision about some children much earlier than at the concluding point of the NIM model, thereby reducing the time the child spends in care before a decision about their future is reached. For cases where SW-SAU feels that non-reunification is the only option from the start, NIM treatment was seen as superfluous and a delay for the child in moving onto adoption or long-term foster care. There was a concern too that legal decision-makers could also argue for a lengthier timescale for parental change that is not in the best interest of the child. This is weighted against the counter- point that NIM’s treatment phase may improve accuracy of decision-making, reduce the likelihood of a child returning into care if they return home and decrease the chance of children from future pregnancies being maltreated. Essentially, the controversy over the NIM treatment phase reflects a broader debate in the child welfare system, and a lack of evidence, about timescales that are in the best interests of the child. Such debate also spans into controversy over which parts of the system create the most delays for children and the timepoint at which it can be confidently decided that

- 42. parents are not going to progress adequately enough to be able to be re- unfied with their children. Debates about timescales resonate with issues of evidence- gathering and professional autonomy. For SW-SAU, being able to make a judgment without a treatment phase exemplified a core value of using professional experience as a key tool for decision- making. A further facet of SW-SAU experience was their reported ability to draw on their involvement with a family in the home setting and often prior to the child’s removal from that setting. According to social workers, however, their professional experience felt un- dermined in Children’s Panels by the clout attributed to health professionals from NIM. This appears to contradict the position of Greiner and Matthews (2016), who theorize that the legal system would value such professional experience in comparison with an evidence-gathering approach (as NIM is based on). However, Greiner and Matthews (2016) specify this position as being related to judges and lawyers and we know less about how such theory translates to other facets of the legal system like the Hearing System in Scotland. We have yet to collect data with lawyers and judges to explore whether social work predictions about the legal reaction to NIM evidence actually reflect the perspectives of the legal profession. In an alternative interpretation, it is possible that health professional status, and related themes of clout (e.g., expertise

- 43. and objectivity) may translate into a perceived notion of professional autonomy. In other words, NIM reports may be seen as being based on health professional opinion rather than from evidence- gathering by what is in fact a multidisciplinary team. Indeed, it was the voice of health professionals from the NIM team at a Children’s Panel – the actual presence of that professional – that was given as an example of clout impact in the findings. If this is the case, Greiner and Matthews’ (2016) theory about the legal system favoring this type of evidence is instead supported. F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 193 Further research should also explore the potential differences that might occur between health professionals’ presentation of evidence verbally, such as in the Hearing System, versus a more traditional legal system pondering written evidence. It is a limitation of this current study that we cannot say more about the relative weights of different forms of evidence in different legal fora, given that participants often spoke generally about “the legal system” without specification. It is plausible that, in court situations, a key feature of NIM’s clout – the presence of the health professional in presenting evidence – may be diluted as the focus shifts onto documented intricate details – a key feature of NIM’s doubt. It

- 44. is possible, therefore, that NIM recommendations about a case are more likely to be upheld by the Hearing System but contested at court-level. 5. Conclusions and future directions The quantitative results of BeST? are eagerly awaited and there is continued uncertainty (a position of equipoise) about whether SW-SAU or NIM offer the best approach to analyzing cases of maltreatment. This is important, not only because it underscores the ongoing need for the trial, but because of the bidirectional relationship between subjective opinion and practice. The clout/doubt theme is applicable beyond BeST? and beyond Scotland; it suggests a central influence of the legal context on the construction of perceptions about what is the ‘best’ assessment evidence upon which to base crucial child welfare decisions. It will be interesting to witness how the clout/doubt theme evolves over time. If it transpires that NIM really does face more legal challenge than SW-SAU, perceptions of clout/doubt may be affected. Similarly, as SW-SAU is proven ‘right or wrong’ in relation to their projections about NIM’s impact, views about clout/doubt may alter. This might be particularly true in relation to the perspective that NIM reflects more favorably on parents than SW-SAU; it is feasible that, over time, this view may be strengthened or diluted as the conclusions of cases are learned. Calls amongst social workers about a need to demonstrate a greater sense of confidence in their

- 45. judgments have the potential to change and re-balance clout perceptions between NIM and SW-SAU. Conversely, it is possible that social workers will – by feeling undermined – inadvertently contribute to panels’ views of NIM’s clout if they convey a comparative lack of certainty. Clashing timescales between NIM and processes in the wider system also renders clout/doubt a changeable theme; for example, when there is a delay between the production of a NIM report and a Children’s Hearing, the clout of the report can flip over to be replaced by doubt about it’s relevance to current day. The passage of time also may alter the clout/doubt theme as experiences of congruence and conflict between the judgments of NIM and SW-SAU are reflected upon. In cases where conflict between the services exists, there is a rationale for further research adopting a case study approach to explore the process by which opposing opinions are managed and the impact that they have in the legal system. This study provides a novel example of the merits of embedding qualitative process evaluation into RCTs in such complex areas of study. Not only will it provide explanatory power to the future results of this particular trial, but it also provides an exploratory platform to analyze how health and social work models sit together in a vital area of public health interest. Tracking the journey of NIM’s introduction into the system allows us to capture how the health/social relationship may evolve over time and the way it

- 46. might inter-relate with any effects of NIM in the wider system. We therefore endeavor to continue to explore the context of NIM and the potential fluidity of clout/doubt as the trial continues. Funding and acknowledgements This work was funded by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) [grant numbers 20130913, IID/ 1/010449942]; the Chief Scientist Office [grant number CZH4629]; and the National Institute of Health Research [grant number 12/ 211/54] We thank the participants in this study for the time taken to share their views in interviews and focus groups. References Beresford, P. (2002). Thinking about ‘mental health’: Towards a social model. Journal of Mental Health, 11(6), 581–584. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. Caspi, A., Houts, R. M., Belsky, D. W., Harrington, H., Hogan, S., Ramrakha, S., et al. (2016). Childhood forecasting of a small segment of the population with large economic burden. Nature Human Behaviour, 1, 1–10 0005. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (2017). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Retrieved 09/02/2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/ acestudy/. Craig, P., Dieppe, P., McIntyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., &

- 47. Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 337, a1655. Dinkler, L., Lundström, S., Gajwani, R., Lichtenstein, P., Gillberg, C., & Minnis, H. (2017). Maltreatment-associated neurodevelopmental disorders: A co-twin control analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(6), 691–701. Dozier, M., Bick, J., & Bernard, K. (2011). Intervening with foster parents to enhance biobehavioral outcomes among infants and toddlers. Zero Three, 31(3), 17–22. Dozier, M., Zeanah, C. H., & Bernard, K. (2013). Infants and toddlers in foster care. Child Development Perspectives, 7(3), 166–171. Glass, S., Gajwani, R., & Turner-Halliday, F. (2016). Does quantitative research in child maltreatment tell the whole story? The need for mixed-methods approaches to explore the effects of maltreatment in infancy. The Scientific World Journal, 1869673. Greiner, D. J., & Matthews, A. (2016). Randomized control trials in the United States legal profession. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 12, 295–312. Johnson, P., & Cahn, K. (1995). Improving child welfare practice through improvements in attorney-social worker relationships. Child Welfare, 74(2), 383. Luke, N., Sinclair, I., Woolgar, M., & Sebba, J. (2014). What works in preventing and treating poor mental health in looked after children? NSPCC. Macintyre, S., Chalmers, I., Horton, R., & Smith, R. (2001). Using evidence to inform health policy: Case study. British Medical Journal, 322(7280), 222–225. Minnis, H., Bryce, G., Phin, L., & Wilson, P. (2010). The spirit of New Orleans: translating a model of intervention with

- 48. maltreated children and their families for the Glasgow context. Clinical Child Psychology And Psychiatry, 15(4), 497–509. F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195 194 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0005 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0010 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0015 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0015 https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/ https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/ http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0025 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0025 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0030 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0030 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0035 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0040 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0045 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0045 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0050 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0055 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0060 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0065 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0070 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0070 Minnis, H. (2016). The Best Services Trial (BeST?): Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the New Orleans intervention model for infant mental health. Lancet Protocol D-15-06090R1, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02653716.

- 49. Moerman, D. E., & Jonas, W. B. (2002). Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136, 471–476. Moore, G., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Cooper, C., et al. (2014). Process evaluation in complex public health intervention studies: The need for guidance. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68(2), 101–102. Oakley, A., Strange, V., Stephenson, J., Bonnell, C., & Allen, E. (2006). Process evaluation in randomized controlled trials of complex interventions. British Medical Journal, 332, 413–416. Oxford Dictionaries (2017). Definition of equipoise in english. Retrieved 09/02/2017, from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/equipoise. Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (2004). Realist evaluation. Retrieved 30/11/2016, from http://www.communitymatters.com.au/RE_chapter.pdf. Porter, R., Welch, V., & Mitchell, F. (2016). The role of the solicitor in the children’s hearings system: Centre of excellence for looked after children in scotland. Pritchett, R., Fitzpatrick, B., Watson, N., Cotmore, R., Wilson, P., Bryce, G., et al. (2013). A feasibility randomised controlled trial of the New Orleans intervention for infant mental health: A study protocol. The Scientific World Journal 838042. Pritchett, R., Hockaday, H., Anderson, B., Davidson, C., Gillberg, C., & Minnis, H. (2016). Challenges of assessing maltreated children coming into foster care. The Scientific World Journal, 5986835. Robinson, M., & Cottrell, D. (2005). Health professionals in

- 50. multi-disciplinary and multi-agency teams: Changing professional practice. Journal Of Interprofessional Care, 19(6), 547–560. Satterfield, J. M., Spring, B., Brownson, R. C., Mullen, E. J., Newhouse, R. P., Walker, B. B., et al. (2009). Toward a transdisciplinary model of evidence-based practice. The Milbank Quarterly, 87(2), 368–390. Turner-Halliday, F., Watson, N., & Minnis, H. (2016). Process evaluation of the New Orleans Intervention Model for infant mental health in Glasgow. Working with infants and their carers after abuse and neglect. NSPCC. Walker, H., Wilson, P., & Minnis, H. (2013). The impact of a new service for maltreated children on Children’s Hearings in Scotland: A qualitative study. Adoption & Fostering, 37(1), 14–27. Webb, S. A. (2001). Some considerations on the validity of evidence-based practice in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 31(1), 57–79. Zeanah, C., Larrieu, J., Heller, S., Valliere, J., Hinshaw - Fuselier, S., Aoki, Y., et al. (2001). Evaluation of a preventive intervention for maltreated infants and toddlers in foster care. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolscent Psychiatry, 40(2), 14–21. Zeanah, C. H., Shauffer, C., & Dozier, M. (2011). Foster care for young children: Why it must be developmentally informed. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(12), 1199–1201. F. Turner-Halliday et al. Child Abuse & Neglect 72 (2017) 184– 195

- 51. 195 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0075 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0075 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0080 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0085 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0085 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0090 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0090 https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/equipoise http://www.communitymatters.com.au/RE_chapter.pdf http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0105 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0110 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0110 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0115 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0115 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0120 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0120 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0125 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0125 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0130 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0130 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0135 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0135 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0140 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0145 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0145 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267-3/sbref0150 http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0145-2134(17)30267- 3/sbref0150Clout or doubt? Perspectives on an infant mental health service for young children placed in foster care due to abuse and neglectIntroductionThe need for quality assessment in the complex world of child abuse and neglectThe introduction and testing of a new model of assessmentUsing process evaluation to explore the context of NIMUsing process

- 52. evaluation to explore the impacts of NIM on decision- makingThis paper – aims and objectivesMethodsFindingsThe clout of mental health assessmentNIM’s health professional input and position in the systemNIM’s in-depth assessment focusA trial of treatmentThe doubt created by a mental health approachThe intricate focus on child-parent interactionA lack of historical relationship with the familyNIM’s trial of treatmentConveying a false possibility of changeThe doubt over undefined timescalesDiscussionOverview of clout/doubt and relation to study aimsThe context and creation of clout/doubt: an adversarial legal systemDecision-making timescales: clout/doubt and ‘certainty versus uncertainty’Conclusions and future directionsFunding and acknowledgementsReferences Child sexual abuse remains a problem in society, often resulting in the long-term placement of children in the foster care system. In Kentucky, children placed in foster care due to sexual abuse spent more time in care when compared with children removed for any other reason (AFCARS, 2013). Given the cost of long-term foster care placement in both human and eco- nomic terms, few studies have specifically explored if any factors help to predict why this vulnerable population spends signifi - cantly more time in foster care. The overarching goal of this exploratory study was to use binary logistic regression to investi- gate whether any child demographic or environmental character - istics predicted the discharge of a child placed in Kentucky’s foster

- 53. care system for child sexual abuse. Results indicated that children in the most rural areas of the state were over 10 times more likely to be discharged from foster care during the federal fiscal year than those residing in the most urban areas. Given this stark reality, a focus must be allocated in understanding this phenomenon. Future research must examine whether the results speak to the necessity of systematic improvement in urban areas or if they are illustrating a unique strength found in rural areas. Child Sexual Abuse and the Impact of Rurality on Foster Care Outcomes: An Exploratory Analysis Austin Griffiths Western Kentucky University April L. Murphy Western Kentucky University Whitney Harper Western Kentucky University 57 Journal_Vol95_1R2_July_Aug 2007 6/1/17 3:40 PM Page 57 In federal fiscal year (FFY) 2014, 3.6 million child abuse and neglectreferrals were made alleging the maltreatment of 6.6 million children in the United States. Of these, approximately 3.2 million

- 54. (48.5%) received either an investigation or alternative response, resulting in 702,208 (21.6%) victims of maltreatment (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). A majority (75.0%) of these children suf- fered neglect, followed by physical abuse (17.0%), sexual abuse (8.3%), other types of abuse (6.8%), and psychological abuse (6.0%) (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). Approximately one-fourth of all cases investigated by child protective services are sub- stantiated (Walsh & Mattingly, 2012), resulting in difficult decisions about whether or not the child can remain safe in their current home environment. At times, decisions are made to seek court intervention and children are placed in foster care. While many studies have con- sidered factors pertaining to reasons for placement, little to no research has been published on factors impacting the length of stay in placement specifically for children experiencing sexual abuse. Child abuse is costly, in both economic and human terms. Wang and Holton (2007) have estimated the annual financial cost of child abuse and neglect was $103.8 billion. However, this annual calculation of direct costs from hospitalizations, mental health services, child wel-

- 55. fare services, and law enforcement is a conservative estimate, only accounting for the costs related to the victims (Wang & Holton, 2007). Although the economic costs associated with child abuse and neglect are substantial, it is essential to recognize the prevailing “intan- gible losses” that can impact the individual, such as pain, suffering, and reduced quality of life. Although difficult to quantify, these losses may represent the largest component of violence against children and should be taken into account when allocating resources (Miller, 1993). Seeking insight into areas to improve the foster care system and its relationship with the young lives depending on it, it is important to explore any factors that may explain longer stays in foster care and if any variables can be found that help children to achieve timely permanency. 58 Child Welfare Vol. 95, No. 1 Journal_Vol95_1R2_July_Aug 2007 6/1/17 3:40 PM Page 58 According to Child Welfare Information Gateway (2013), children who have been sexually abused have had both their physical and