Disability Essay

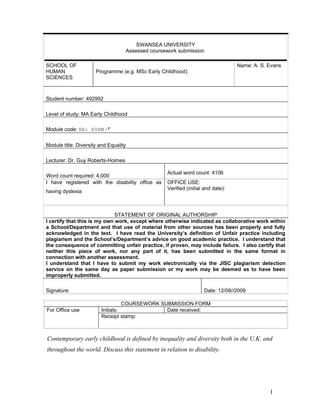

- 1. SWANSEA UNIVERSITY Assessed coursework submission SCHOOL OF Name: A. S. Evans HUMAN Programme (e.g. MSc Early Childhood): SCIENCES Student number: 492992 Level of study: MA Early Childhood Module code: RE: EYXM ٠٣ Module title: Diversity and Equality Lecturer: Dr. Guy Roberts-Holmes Actual word count: 4106 Word count required: 4,000 I have registered with the disability office as OFFICE USE: Verified (initial and date): having dyslexia STATEMENT OF ORIGINAL AUTHORSHIP I certify that this is my own work, except where otherwise indicated as collaborative work within a School/Department and that use of material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged in the text. I have read the University’s definition of Unfair practice including plagiarism and the School’s/Department’s advice on good academic practice. I understand that the consequence of committing unfair practice, if proven, may include failure. I also certify that neither this piece of work, nor any part of it, has been submitted in the same format in connection with another assessment. I understand that I have to submit my work electronically via the JISC plagiarism detection service on the same day as paper submission or my work may be deemed as to have been improperly submitted. Signature: Date: 12/08//2009 COURSEWORK SUBMISSION FORM For Office use Initials: Date received: Receipt stamp: Contemporary early childhood is defined by inequality and diversity both in the U.K. and throughout the world. Discuss this statement in relation to disability. 1

- 2. There are many issues of inequality and diversity surrounding the area of childhood disability however this essay will focus on three key areas • Eugenics • labelling • Models of disability. Eugenics is the study of, or belief in, the possibility of improving the qualities of the human species. This can take the form of discouraging reproduction by people who may have genetic defects or presumed to have inheritable undesirable traits. It is argued that eugenics has been replaced by genetics in the search for the solution to imperfections within society. This has wider implications for children born or yet to be born with disabilities. This essay will consider the subtle shift from eugenics to genetics which has surfaced in a number of aspects within professional practice. Labelling disability has been a long term practice within the medical and educational establishment. Historically children with disabilities have been labelled with terms according to their physical or mental disabilities, e.g. severely physically handicapped, retarded, etc. This essay will consider the implications of labelling children with disabilities. In the U.K. the predominant models used in disability are the medical model and the social model. Both these models are used by professional agencies in medicine, education and social work when dealing with children with disabilities. Disability movement groups have moved towards the social model. This essay will look at the positive and negative effects of both models on children with disabilities. Eugenics – Genetics 2

- 3. According to Michael Roe (2000) there has been a new surge of interest in genetic technologies. Roe (2000) suggests that this interest is fed by dangerously unexamined assumptions that resemble old style eugenics. Roe (2000) argues that the promotion of genetic technologies contain the unexamined belief that such developments are for humanities benefit. The search for perfection, physical, psychological and behavioural is what appealed to eugenicists in the early part of the 20th Century. One could argue that eugenics played a part in the mass genocide of millions of people in Nazi Germany. Vast numbers of children deemed to be imperfect were put to death in concentration camps. Baker (2002) suggests that one of the significant differences between eugenics and genetic practices are • eugenics is aimed at the prevention of fertility of the unfit • genetic practices are orientated toward the management of conception In reconsidering the issues of sameness, difference, equality and democracy in the public school system in America, Baker (2002) focuses on the question of disability. Baker (2002) suggests that disability becomes reinscribed as “outlaw ontology” outlaw ontology can be defined as ‘a way of being or existing outside the normal and as such needing to be chased down’. According to Baker (2002) there is a shift in debates around inclusive schooling and mainstreaming. Baker (2002) argues that the point of prohibition is relocated suggesting that instead of telling a child they simple cannot attend a normal school the child perceived as having disabilities of a certain kind can now be problemised, marginalised and managed within the mainstream institution. Campbell (2000) suggests that eugenics is seeking to eliminate the birthing of bodies marked as disabled. Campbell argues that if bodies marked disabled are born then the activity of the posse switches to trying to ‘perfect’ the ‘defective’ body or mind and make it normal. According to Campbell (2000) new eugenics has taken three forms. • prenatal screening • disability dispersal policies • compulsion towards perfecting and morphing technologies of normalization 3

- 4. Crowe (2000) argues that new eugenics is a discreet movement. Crowe (2000) suggests that the terms of genetic discourse are different from old-style eugenics. According to Crowe (2000) this is apparent in those proposals that seek out defects by prenatal screening turning motherhood into decisions about what kinds of bodies to give birth to. Baker (2000) argues that disability dispersal policies and perfecting technologies ( the use of science and technology to improve human mental and physical characteristics and capacities) relate directly to schooling and stresses the importance given to studying the wider implications of the hunt for disability in public education. Baker (2000) notes the proliferation of categories of educational disability used to mark students as outside norms of child development or as at risk of school failure. Studies have revealed an abysmal record of underachievement for youth with disabilities. A study by Phelps and Hanley-Maxwell (1997) found that the dropout rate for youth with disabilities far exceeded those of non-disabled students by nearly a factor of two. The employment and further education opportunity also falls below levels of non disabled peers. Even when the students with disabilities found employment their wages were just above the minimum wage with limited prospects for promotion. Disabilities can have negative effect for young people limiting access to education and employment which can lead to economic and social exclusion. In this type of climate one could question whether or not children should be labelled with a disability. Definition and Labelling of Disability The definition of disability and disabled person according to the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 is: (1) Subject to the provisions of Schedule 1, a person has a disability for the purposes of this Act if he has a physical or mental impairment, which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on his ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. 4

- 5. (2) In this Act “disabled person” means a person who has a disability. Historically there have been a number of terms used to label children’s disabilities. Some of these have been less than complimentary, deep-rooted in negative attitudes towards the disabled. The terms ‘spaz’, ‘reject’, ‘mong’, ‘spesh’, etc have all found their way into contemporary ways of referring to the disabled child. One could argue that some form of labelling is a necessity for certain individuals in order for them to access services and benefits. Children with dyslexia, attention deficit disorder or autism require labelling before accessing educational, medical or community based services. It was not until the Warnock Report on Special Educational Needs (DES, 1978) that the term learning difficulties was used to describe a broader group of children exhibiting difficulties in learning. The Children Act (1989) defines children in need as: • Those who are unlikely to achieve or maintain a reasonable standard of health or development unless the local authority provides services • Those whose health or development is likely to be significantly impaired unless the local authority provides services; and • Disabled children The process of labelling disabled children can encourage negative perceptions of the child. According to Jones and Bilton (1994) there may be some sense in negative attitudes to disabled people including children and that these attitudes reflect the negative status of disabled people in society. Jones and Bilton (1994) argue that all children have needs and those children ‘in need’ and children with ‘special needs’ are not separate groups. Jones & Bilton (1994) suggest that the availability, adequacy and quality of primary and universal services are an important determinant of the extent to which there are children in need. Swain et al argue that being labelled, as ‘in need’ can be pathologising as well as implying that there is some intrinsic problem in the child. Swain et al (1993) suggest that needs should not be seen as shortfalls in the individual or family but as an opportunity for development. 5

- 6. Lewis (1995) suggests that discussions about children’s needs are complicated by the diversity of and use of different definitions. Lewis (1995) argues that there is no straightforward relationship between disability label and educational provision. According to Mehan et al (1986) when a child is officially labelled as handicapped or learning disabled it becomes a social fact about the child and they become instantly restricted and limited by the boundaries established by mythic discourse. Swain (1993) suggests that being labelled is a fact of life for disabled people. Swain (1993) argues that without surrendering to these labels there is no other way of gaining access to services and welfare benefits and as such ends the possibility of maintaining that an individual or group is not disabled. There is evidence to suggest that disabled children from ethnic minority groups face a form of double or simultaneous oppression. Carby (1982) used the term ‘simultaneous oppression’ to describe the experiences of black, radical feminist writers in the 1980’s. According to Carby (1982) these women were subject to simultaneous oppression of patriarchy, class and race, which rendered their position and experiences as marginal and invisible. Stuart (1993) identifies three areas where black disabled people experience a distinct form of simultaneous oppression • Limited or no individual identity • Resource discrimination • Isolation within black communities and the family Stuart (1993) suggests that each of these areas is influenced by the ideas of new racism. Stuart suggests that this new racism is based on cultural differences and places black disabled people at the margins of the ethnic minority and disabled populations. Studies in the U.S. during the 1980’s (Argulewicz, 1983; Carrier, 1986; Sleeter, 1987) found an over representation of working class and minority children in the classification of children with learning difficulties. In the U.K. Tomlinson (1984) found that there was an over representation of children of immigrants from the Caribbean in the category of 6

- 7. educationally subnormal relative to the percentages of the population. Tomlinson (1984) argues that arbitrary labelling of these children resulted from personality clashes between teacher and student however some argue that there are other reasons. Thomas and Glenny (2000) claim that emotional and behavioural difficulties are bogus needs in a false category. Thomas and Glenny (2000) suggest that where children from working class families and minority children are over represented the question arises as to whether such categories are purely a biomedical (medical research) phenomenon or confusion between administrative need and quasi-medical categorizing. Tomlinson (1984) suggests that the determination of educational or academic disability was culturally biased with little or no biomedical or neurophysiologic base. According to Tomlinson children from Caribbean families were over represented in the labelling process initiated by white teachers. Tomlinson (1984) concluded that what was being labelled was not simply the child but a culture. Prejudicial attitudes toward disabled people and, indeed, against all minority groups, are not inherited. They are learned through contact with the prejudice and ignorance of others. Challenging discrimination became a necessity for groups of people including homosexuals and African Americans. From the 1950’s onwards women, black people and homosexuals were involved in challenging prevailing definitions by challenging the language used to underpin the definitions. They did this by creating, substituting or taking over terminology to provide a more positive image including terms like ‘black is beautiful’, gay is good, etc. Some argue that redefinitions of labels may be the way forward for disabled people. Oliver (1990) suggests that labels or definitions are important for minority groups and that if social problems are to be resolved they required a fundamental redefinition of the problem itself. Labelling of children with disabilities has spread though usage in a number of different areas. Rieser (2002) argues that some powerful and pervasive views of the disabled are reinforced in the media, books, films, comics, art and language. Many disabled people 7

- 8. internalise negative views of themselves. These negative views can create feelings of low self-esteem and achievement. This reinforces non-disabled people's assessment of disabled people’s worth. Baker (2000) argues that in the public school system in the U.S. labels are usually what qualify a child for special educational services. Similarly in the U.K. children are routinely labelled with A.D.H.D. (attention deficit disorder), B.D. (behavioural difficulties), D.C.D. (developmental coordination disorder), etc. Baker (2000) suggests that the use of acronyms for labelling children has become a phenomenon. Baker (2002) suggests that one could choose any letter of the alphabet and place a ‘D’ after it to find a category defining a school aged child as a problem which requires recording in school files. Baker suggests that these new disability nomenclatures are not just new ways of speaking about children and their development. Baker (2002) argues that they represent a shift from the moralization of disability to the medicalisation of disability during the 20 th Century. Jaques-Stiker (1999) debates what incites the fever for classification and the passion for sameness. Jaques-Stiker (1999) argues that the question we have forgotten to ask is ‘why is disability called dis-ability’? Jaques-Stiker (1999) questions why people who are born or become different are referred to by so many names. Baker (2000) suggests that there has been a swarming effect around the hunt for and diagnosis of disability as a negative ontology used by schools. Baker (2000) suggests that the schools are actively seeking to name and remedy disabilities with best intentions. Rieser (2002) argues that the models of disability in use by professionals today can create a cycle of dependency and exclusion, which is difficult to break.’ There are different models of disability which claim to cater for the needs of disabled people including children. The two main models of disability in use in the U.K. are the ‘medical model’ and the ‘social model’. The Medical Model of Disability 8

- 9. The medical model of disability has been defined as A model by which illness or disability is the result of a physical condition, is intrinsic to the individual (it is part of that individual’s own body), may reduce the individual's quality of life, and causes clear disadvantages to the individual. Wikipedia (2009) Oliver (1990) suggests that the predominant concept of disability in the U.K. is that it is regarded as a personal tragedy requiring medical attention. Richard Rieser (2002) argues that the medical model of disability sees the disabled person as the problem, which has to be fitted into the world as it is. Historically disabled children have been placed in ‘special’ schools, institutions or isolated at home. Rieser (2002) argues that in these circumstances the emphasis is on dependence backed up by stereotypes of disability. Society has traditionally valued physical and mental perfection as well as independence. Anyone displaying the opposite, i.e. physical and or mental imperfection being dependent have been pitied or patronised. Some parents argue for inclusion through integration for their child because they do not want them segregated from the rest of the school-going population. Szivos (1992) suggests that we should ask ourselves whether in denying labels we are also denying and devaluing ‘difference’. Rieser (2002) suggests that people should be encouraged to view the issue of including disabled children from a human rights and equality perspective rather than seeing the child as ‘faulty’. This view is supported by Uditsky (1993) who argues for a set of principles which ensures that the student with a disability is viewed as a valued and needed member of the school community in every respect. This view is supported by Mercer et al (1997) who argue for an inclusive approach. Swain et al (1993) suggest that the overriding political feature of interventions administered by the medical profession is that it brings all disabled people together under a single medical interpretation of the cause behind their marginalized position in society. Rieser (2002) believes that the medical model of disability is a powerful tool used by 9

- 10. medical and associated professions to determine many aspects of the lives of disabled people. Rieser suggests that these ‘usually non-disabled professionals’ decide on • Where disabled people go to school, • What support they get • What type of education they get • Where they live • Whether or not they can work and what type of work they can do • Whether or not they are born at all • Whether they are allowed to procreate Rieser argues that the same control is exercised over the disabled by the built environment. Rieser argues that the disabled life chances are curtailed because their needs are not being met. Rieser suggests that these barriers exist in work, school, leisure, entertainment facilities, transport, training, higher education, housing, personal, family and social life. Participation and equality for the disabled can be hindered by the negative attitudes of ‘able’ people in families, communities, government and some voluntary sectors. Swain et al (1993) suggest that another model has emerged which is based on community-based service providers. Swain et al argue that contrary to helping disabled people have greater control over their lives the community –based providers have wider perspectives than their medical colleagues which leave disabled people with little to do for themselves. Swain et al suggest that the community worker is there to provide expert advice on everything from the architecture of the disabled person’s home to the intimacies of their personal and sexual problems. This form of intervention has been described as leaving the disabled person as ‘socially dead’ Miller & Gwynne (1972). Swain (1993) suggests that disabled people have had to pay a price for the benefits of a needs based provision, which includes invasion of privacy by an army of professionals. Swain et al suggest that the disabled are socialized into dependency because the services are provided for them rather than with them. Swain (1993) suggests that voluntary 10

- 11. organisations and the media continue to promote negative images of children with disabilities accentuated by televised events like ‘Children in Need’. One study found that disabled children ‘appear to have been conditioned into accepting a devalued role as sick, pitiful and a burden of charity’ (Hutchinson and Tennyson, 1986, p.33). We all have different needs, and different weaknesses. Palme (2000) believed that the society in which we live should never be formed on the basis of the special demands by the few. Palme (2000) suggested that society must be formed in such a way that it will suit all and that the needs of disabled persons must influence the planning of our societies as much as the needs of non-disabled persons. Palme (2000) suggested that this should happen not because we must pay special attention to the disabled, but because they are citizens of the society as everyone else. Palme (2000) argued that the needs of the disabled must be included in the building of the society as a matter of course’. This view could be considered as supporting the social model of disability The Social Model of Disability The social model of disability proposes that systemic barriers, negative attitudes and exclusion by society (purposely or inadvertently) are the ultimate factors defining who is disabled and who is not in a particular society. Wikipedia (2009) The 'social model' of disability views the barriers that prevent disabled people from participating in any situation as what disables them. The 'social model' arises from defining impairment and disability as very different things. Crowe, C. (2000) suggests that the social model of disability has changed the lives of disabled people considerably. Crowe (2000) argues that the physical disability is not responsible for difficulties disabled people face. Crowe argues that external factors, barriers created by society are responsible. Crowe (2000) suggests that because these restrictions had been created by society then society could solve them. 11

- 12. Silburn (1988) carried out research into the expressed needs of young disabled people in North Derbyshire. The research was based on seven needs which were defined by the young disable people themselves. They included the need for • Information on aspects of benefits, services and opportunities. • access to everyday facilities • barrier free accommodation for independence • technical aids for independent living • personal assistance when required and controlled by the disabled person • counselling for the same reasons as able bodied people • barrier free transport Swain et al (1993) suggest that the integrated living teams involved in the North Derbyshire project are operating at the interface of social and medical models of care. Swain et al (1993) suggest that the rehabilitation of the disabled dominates the medical model. According to Swain et al (1993) rehabilitation is a vast area of the health service which is underpinned by research departments in universities. Swain et al (1993) question to what extent disabled people would want to be rehabilitated if they lived in a world with decent wheelchairs and a barrier free environment. There are a number of other issues which affect the young disabled and cross both the medical and social model of disability. There is evidence (H.M Government 2006) which suggests that disabled children are at increased risk of abuse, and that the presence of multiple disabilities appears to increase the risk of both abuse and neglect. In the report Working Together to Safeguard Children (2006) it is argued that disabled children may be especially vulnerable to abuse for a number of reasons. These reasons include the fact that disabled children • have fewer outside contacts than other children 12

- 13. • receive intimate personal care from a number of carers, which may both increase the risk of exposure to abusive behaviour and make it more difficult to set and maintain physical boundaries • have an impaired capacity to resist or avoid abuse • have communication difficulties that may make it difficult to tell others what is happening • be inhibited about complaining because of a fear of losing services • be especially vulnerable to bullying and intimidation and/or be more vulnerable than other children to abuse by their peers In order to safeguard disabled children the report suggests that particular attention should be paid to promoting high standards of practice and a high level of awareness of the risks of harm. The recommended measures in the report are more in line with the social model of disability than the medical model. The recommendations include • strengthening the capacity of children and families to help themselves • making it common practice to help disabled children make their wishes and feelings known in respect of their care and treatment • ensuring that disabled children receive appropriate personal, health and social education (including sex education) • making sure that all disabled children know how to raise concerns, and giving them access to a range of adults with whom they can communicate Conclusion 13

- 14. In the early part of the 20th Century Eugenics was considered as a realistic way of solving a number of social, physical and psychological problems in society. One can only imagine what sort of atrocities children suffered in the concentration camps of Nazi Germany in the name of Eugenics. Roe, Baker & Campbell (2000) bring our attention to a renewed form of eugenics reinscribed as genetics. Prenatal screening, disability dispersal policies and genetic practices towards the management of conception are all included in new eugenics. One could argue that society is heading towards the elimination of disabilities and therefore it is a matter of time before the issues of diversity and equality for disabled children will no longer exist. Campbell (2000) makes the point that for the child already born disabled scientists are involved in trying to perfect the disability itself. With developments in prenatal screening and genetic research prospective parents are now faced with ethical, religious, moral, physical, financial and emotional considerations as to whether they give birth at all to what might be a child with disabilities. Children who are born with a disability are protected by a number of rights including the Children’s Act 1995 and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. In order to access services and benefits children have had to be labelled with a specific disability. Jones & Bilton make the point that all children have needs and that children are only in need if there are limited, inadequate, quality primary and universal services. Given that this is the case one could argue that labelling children with a disability instantly restricted by the boundaries of mythic discourse on disability. Tomlinson (1984) makes the point that an over representation of children from these groups occurs through a combination of administrative and medical needs. It is argued that this categorisation is prejudiced towards children from minority groups. There has been a rise in the amount of 14

- 15. nomenclature used to categorise children’s difficulties leading Baker (2000) to describe it as ‘a phenomenon’. The medical model of disability sought to place children in institutions segregated from their able bodied peers. The pervasive view of these children was that they were pitied and patronised. The child was seen as having a problem outside of the ‘norm’. The social model argues that society creates the disability. The social model attempts to remove social barriers for the disabled. Both models can work together in addressing the multitude of issues surrounding issues of equality and diversity in childhood disability. There is evidence that when young disabled people are given the opportunity to participate fully in the decision making process they achieve a greater independence. 15

- 16. References: Argulewicz, E. N. (1983) Effects of Ethnic Membership, Socio-Economic Status and Home Language on LD, EMR, and EH Placements. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 6 (Spring), 195-200. Baker, B. (2002) the Hunt for Disability: The New Eugenics and the Normalization of School Children. Teacher’s College Record. Vol 104, No 4, June 2002, pp 663-703. Campbell, F. (2000) Eugenics in a Different Key? New Technologies and the “conundrum” of “disability”. In M. Crotty, J. Germov, & G. Rodwell (Eds.), “A Race for a Place”: eugenics, Darwinism, and Social Thought Practice in Australia. Pp. 307-318. Newcastle, AU: The University of Newcastle Press. Carby, H. (1982) Black Feminism and the Boundaries of Sisterhood, in the Empire Strikes Back: Race and Racism in 70s Britain, Hutchinson, London. Carrier, J. G. (1986) Learning Disability: Social Class and the Construction of Inequality in American Education. Vol. 18. New York: Greenwood Press. Children’s Act (1989) H.M.Government. Crowe, C. (2000) Inheriting Eugenics? Genetics, Reproduction and Eugenic Legacies. In M. Crotty, J. Germov, & G. Rodwell (Eds.), “A Race for a Place”: Eugenics, Darwinism, and Social Thought Practice in Australia. Pp. 173- 180. Newcastle, AU: The University of Newcastle Press. Disability Discrimination Act (1995). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_model_of_disability 16

- 17. Hutchinson, D. & Tennyson, C. (1986) Transition to Adulthood: A Curriculum Framework for Students with Severe Physical Handicap. London. Further Education Unit. Jones, A. & Bilton, K. (1994) The Future Shape of Children’s Services. London. The National Children’s Bureau. Jaques-Stiker, H. (1999) A History of Disability. University of Michigan. University of Michigan Press. Lewis, A. (1995) Children’s Understanding of Disability. New York. Routledge. Mehan, H, Hertweck, A. & Meihls, J.L (1986) Handicapping the Handicapped. Decision Making in Student’s Careers. Stanford, California. Stanford University Press. Mercer, G & Barnes, C. (1997) Breaking the Mould? An Introduction to Doing Disability Research. Leeds. The Disability Press. Miller, E.G. & Gwynne, G.V. (1972) A Life Apart, London, Tavistock Press. Oliver, M (1990) the Politics of Disablement. London. Macmillan. Palme, O. (2000) Prime Minister of Sweden, cited in DFID, 2000: 5 Phelps, L. and Hanley-Maxwell, C. (1997) School-to-Work Transition for Youth with Disabilities: A Review of Outcomes and Practices. Review of Educational Research.1No 67.pp197-226. Rieser, R. (2002) http://inclusion.uwe.ac.uk_by Richard Rieser, Director, Disability Equality in Education (DEE) 2002. 17

- 18. Roe, M. (2000). Eugenics’ challenge to Liberal Humanism: A Personal traverse. In M. Crotty, J. Germov & G. Rodwell (Eds.), “Race for a Place”: Eugenics, Darwinism and Social Thought and Practice in Australia. Pp 235-247. Newcastle AU: The University of Newcastle Press. Silburn, R. (1988) Disabled People: Their Needs & Priorities, Benefits Research Unit. Department of Social Policy and Administration. University of Nottingham. Sleeter, C. (1987) Why is there Learning Disabilities? A Critical Analysis of the Birth of the Field in its Social Context. In T. Popkewitz (Ed), The Formation of School Subjects: The Struggle for Creating an American Institution. Pp 224-232. New York. Falmer Press. Stuart, O. (1993) Double Oppression: An Appropriate Starting Point? In J. Swain, V. Finkelstein, S. French & M. Oliver (Eds), Disabling Barriers-Enabling Environments. London, Sage Publications. Swain, J, Finkelstein, V, French, S. & Oliver M. (1993) Disabling Barriers – Enabling Environments. London. Sage Publications. Szivos, S. (1992) The Limits to Integration? In Normalisation: A Reader for the Nineties. (H. Brown & H. Smith Eds) London. Routledge. Thomas, G. & Glenny, G. (2000), Emotional & Behavioural Difficulties: Bogus Needs in a False Category. Discourse, 21 (3), 283-298. Tomlinson, S (1984) Educational Subnormality: A Study in Decision-Making. London. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Uditsky, B. (1993) From Integration to Inclusion: The Canadian Experience. In R. Slee (Ed) Is There A Desk with My Name on It? The Politics of Inclusion. New York. Routledge. 18

- 19. Warnock, M. (1978). Report on Special Educational Needs. DES Working Together to Safeguard Children. (2006) A Guide To Inter-Agency Working to Safeguard the Welfare of Children. H.M. Government. 19