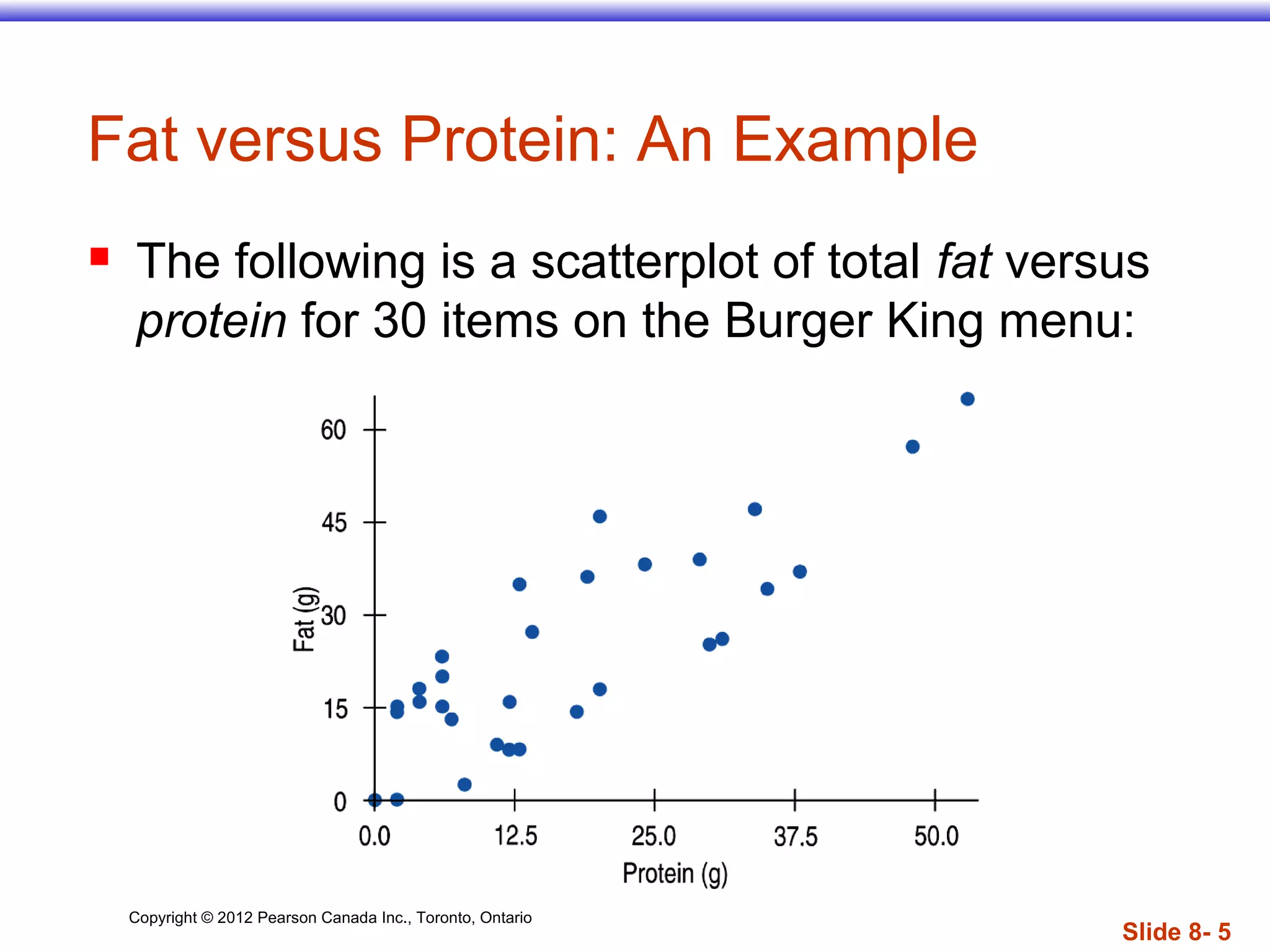

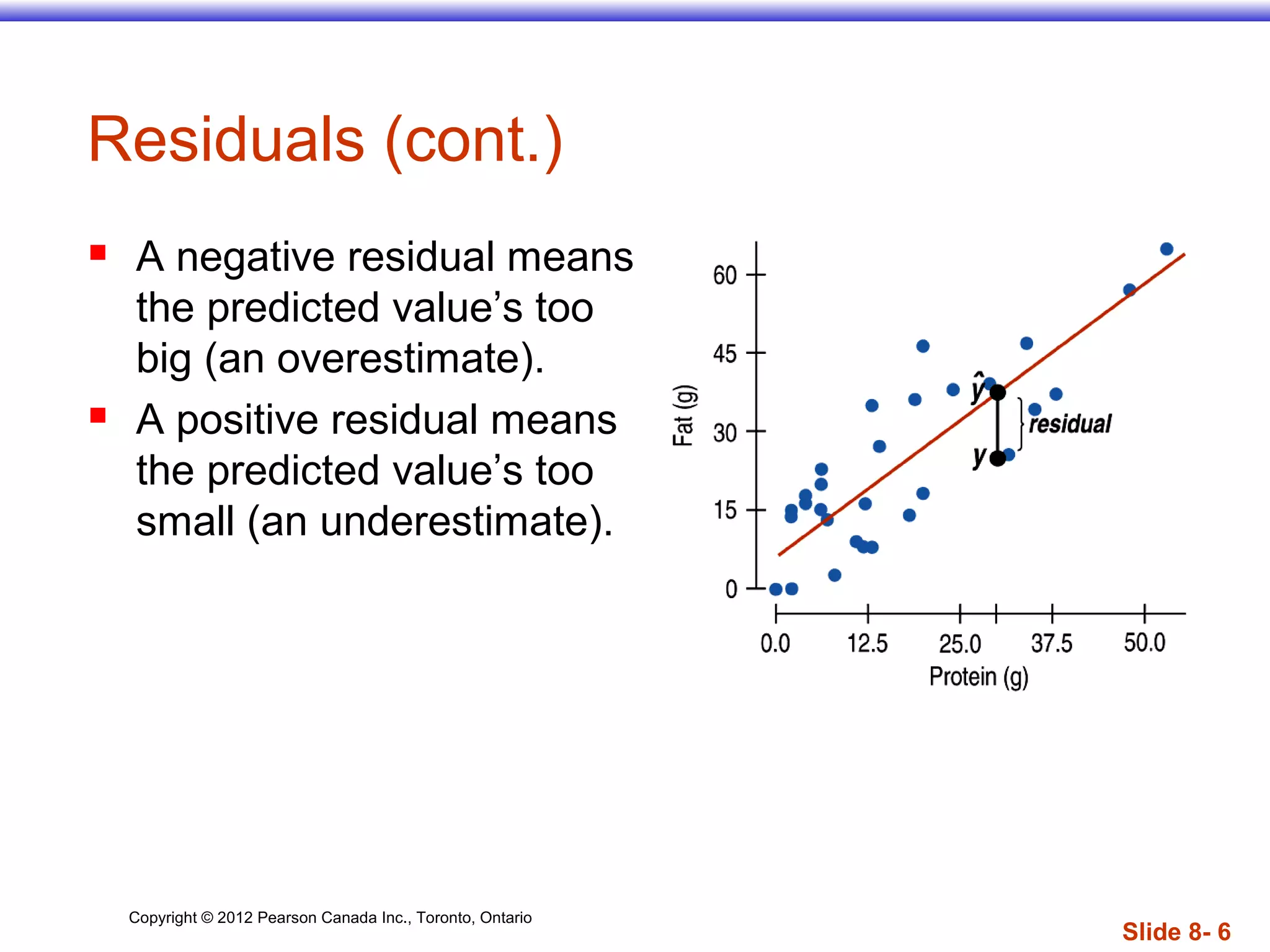

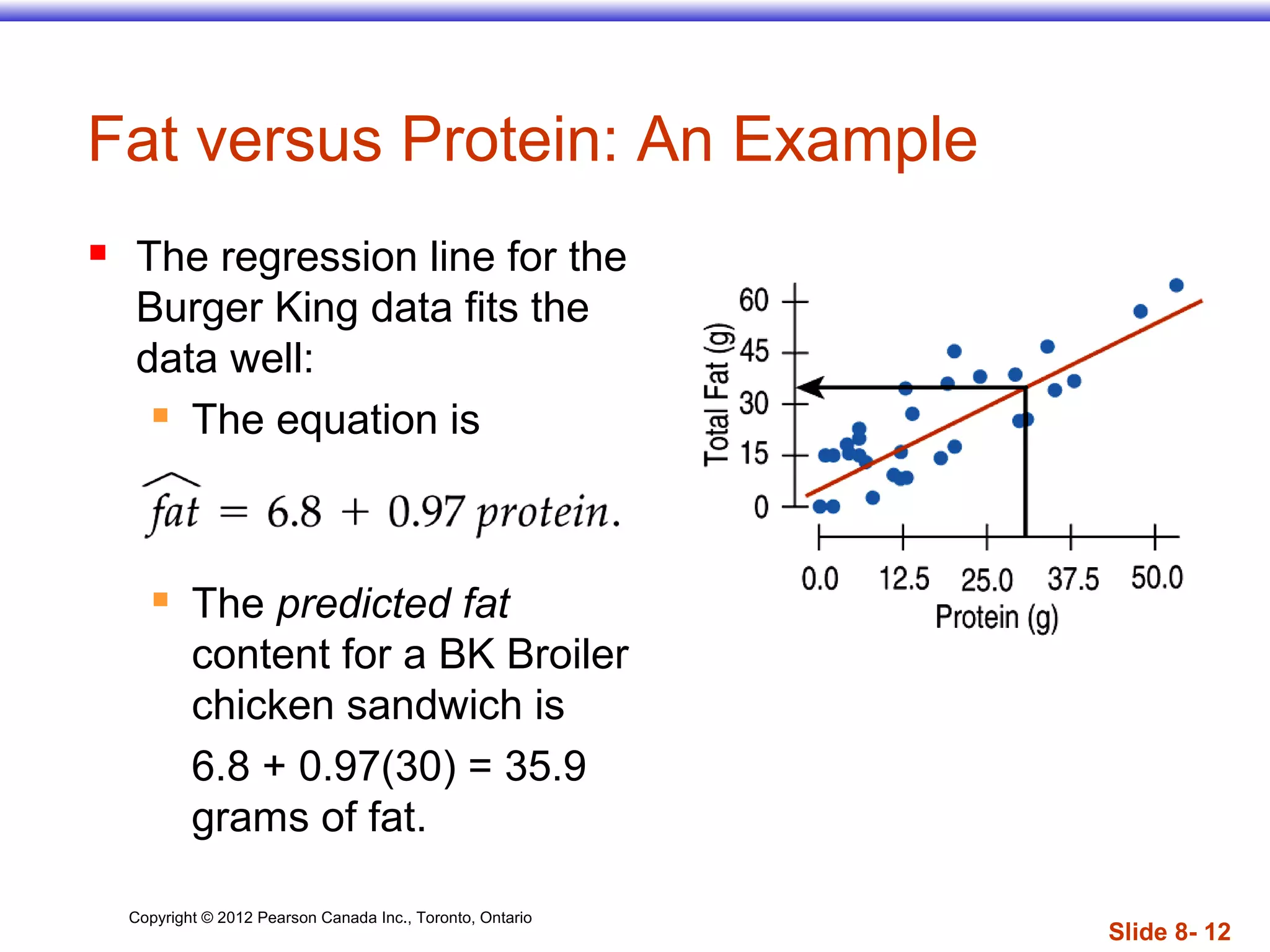

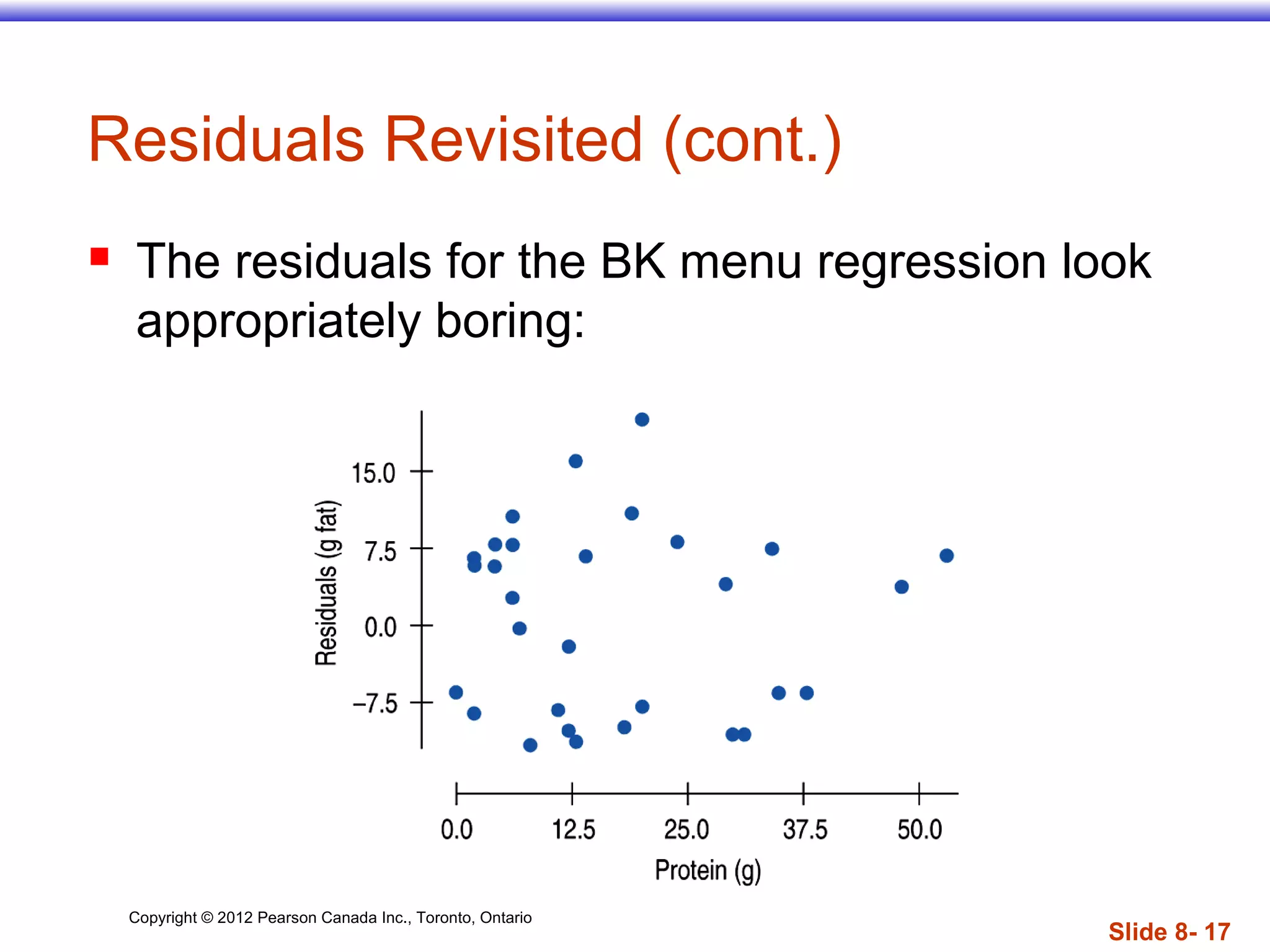

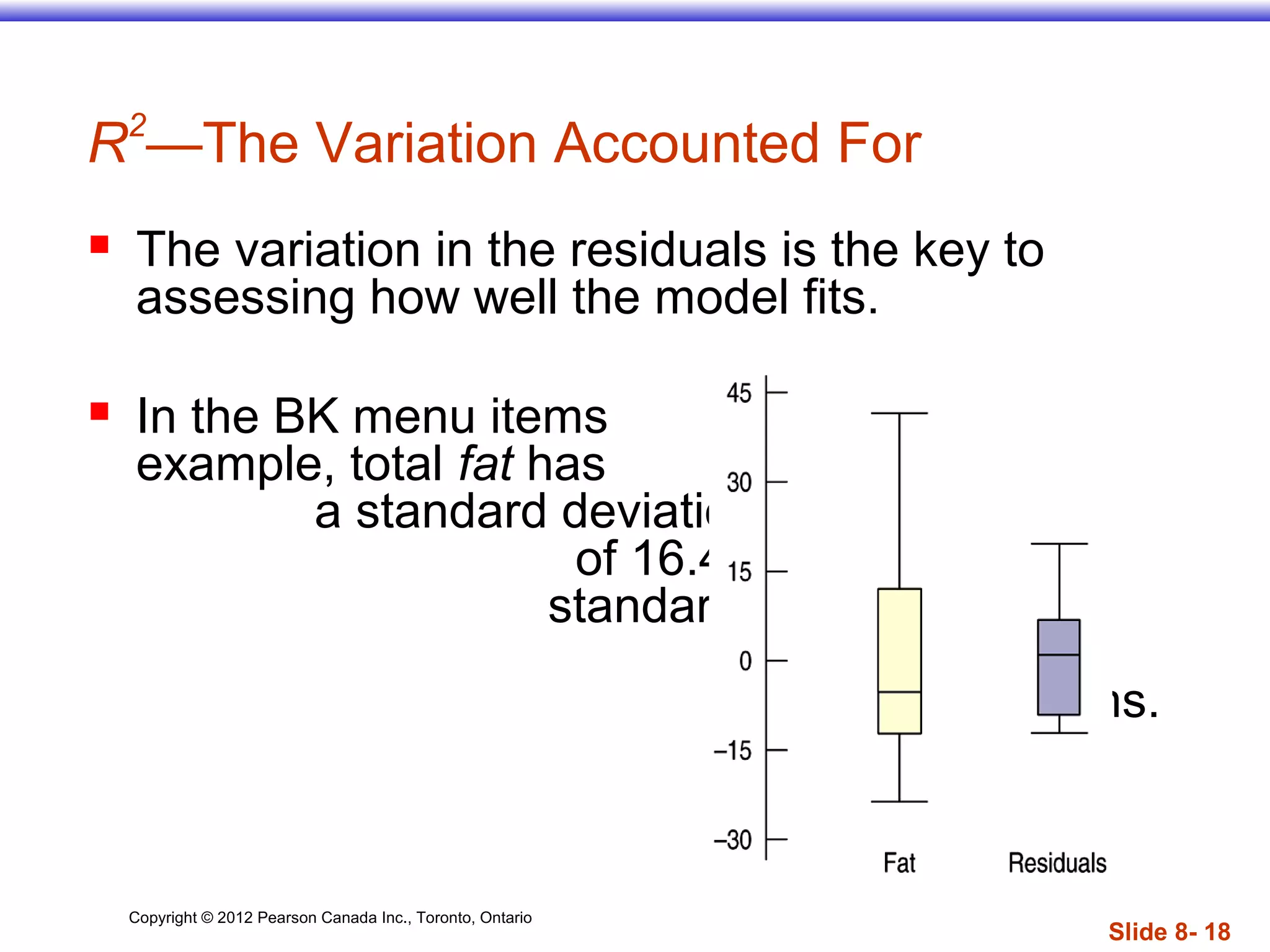

The document discusses linear regression models, which provide a linear equation to model the relationship between two quantitative variables. A linear regression finds the line of best fit that minimizes the sum of squared residuals between observed and predicted values. The regression outputs include the slope, intercept, and R2 value, which indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the model. Key assumptions are that the variables have a linear relationship, there are no outliers, and the residuals are randomly distributed with no discernible pattern.