Case Scenario – Week 1 Project CharterBackgroundYou ar.docx

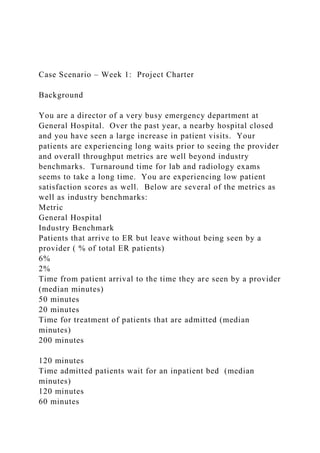

- 1. Case Scenario – Week 1: Project Charter Background You are a director of a very busy emergency department at General Hospital. Over the past year, a nearby hospital closed and you have seen a large increase in patient visits. Your patients are experiencing long waits prior to seeing the provider and overall throughput metrics are well beyond industry benchmarks. Turnaround time for lab and radiology exams seems to take a long time. You are experiencing low patient satisfaction scores as well. Below are several of the metrics as well as industry benchmarks: Metric General Hospital Industry Benchmark Patients that arrive to ER but leave without being seen by a provider ( % of total ER patients) 6% 2% Time from patient arrival to the time they are seen by a provider (median minutes) 50 minutes 20 minutes Time for treatment of patients that are admitted (median minutes) 200 minutes 120 minutes Time admitted patients wait for an inpatient bed (median minutes) 120 minutes 60 minutes

- 2. Length of stay for patients that are discharged from the ER (median minutes) 180 minutes 120 minutes Patient Satisfaction 30th percentile 75th percentile (Hospital goal) Your Chief Operating Officer (COO) and Chief Nursing Officer (CNO) have asked you to serve as a team lead and put together a multi-disciplinary team to identify the reasons for the throughput delays and put together a plan to improve the above metrics over the next 4-6 months. The boundaries are that no additional staff can be hired and there are no capital dollars available for use. The Chief Nursing Officer will be the executive sponsor and would like to see a project charter prior to kicking off the project. The Assignment 1. Based on the above scenario and details, complete the yellow portions of the below sample Project Charter. Each section should be approximately 3-5 sentences. Each box is worth 15 points. Total possible points= 90 points. 2. What questions will you ask your sponsor when reviewing the charter for sign-off? List 2-4 questions below. This answer is worth 10 points. Your Name: Haley Butler__________________ Course 4310 Date: September 3, 2014________________ Market / Location: Project Lead: Sponsor:

- 3. Sign Off: RVP: Sign Off: Phase Timeline: Date: Date: Date: Date: Date: Identify/Charter Assess Improve Deploy

- 4. Sustain Type Response to #2: Section 3: Project Scope (Team Boundaries) Section 1: Problem Statement – Opportunity (Background) Section 4: Team Composition Section 2: Project Goal w/ Metric & Initial Measure

- 5. Section 5: Project Resources Business Case (ROI) and Patient Impact Section 6: Stakeholders & Stakeholders’ Communication Plan

- 6. ABOUT US ADVERTISE / EXHIBIT MEDIA KIT SUBSCRIBE CONTACT US RSS FEED SEARCH Training Conference & ExpoTraining Conference & Expo Online Learning ConferenceOnline Learning Conference Live+OnlineLive+Online Training Mag NetworkTraining Mag Network Training Top 125Training Top 125 Article Author: Lorri Freifeld TRANSFER OF TRAINING: MOVING BEYOND THE BARRIERS A new model helps promote training transfer to the workplace. Posted: April 6, 2012 By Alexis Belair Q: How can I produce skilled learners in the workplace? A: It’s simple! Teach for Transfer! Would such a succinct response to a posed question on the development of skilled professionals be sufficient for its understanding? A swift, “No,” probably would be the answer. With the concept of “teaching for transfer” at the forefront of any training program, it has become vital to understand the concept beyond its surface. Would it be sound to declare that the use of the word, “simple,” to describe the method of “teaching

- 7. for transfer” is somewhat of an understatement? The correct answer most likely would be, “Definitely!” With a mere 10 to 20 percent of information being transferred to the workplace post-training, it is evident the methodology has its complexities. There is a need to develop a greater understanding of the principle. Consequently, the issue deeply rooted in the methodology is not this peripheral understanding of the concept, but rather the lack of best practices used for bolstering transfer in training. In reference to the above, the word, “simple,” would be an erroneous representation of the method of teaching for transfer. An attempt to implement the technique is admirable, but this does not suggest effectiveness. Research has shown that even the most successful training programs fail to transfer knowledge and new skills to learners (Cheng, 2008). Today, organizations strive for knowledgeable and skilled employees in order to improve organizational performance (Burke, 2008). In light of this, what are the factors that are being overlooked when trying to execute the practice? Undoubtedly, there is a need to understand the process in order to target some of its glitches. Factors in the Transfer Process

- 8. The idea that “training needs to be demonstrably effective” is the epitome of any learning outcome (Cheng, 2008). Although evaluation models, such as Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Evaluation, have been used to measure deficiencies in performance, the challenge is in finding training solutions that will achieve the intended objectives and mold learners into idyllic performers. Notwithstanding the complexities of training, it is indisputable that the true success of training is represented in the learner’s ability to demonstrate what has been learned. It is, thus, irrefutable that training well done is, in fact, worthy of investment (Cheng, 2008). The school of “situated learning” has deemed the learner’s ability to participate in their environment a supreme technique for acquiring skills (Cheng, 2008). However, the idea that off-the-job training is of little value can only be considered gaudy from the stance of any professional. Authors from the article “Transfer of training: A review and new insights” offer an exemplary rendering of the acquisition of “core skills” (2008). A balanced combination of on-the-job and off-the-job learning is preferable. Trainee personalities also play a vital role in the transfer process. “The main goal for training designers

- 9. should be to foster the trainees’ motivation to use new skills on the job” (Liebermann and Hoffmann, 2008). Overall learner satisfaction is greater if the training is relevant to the job. In alignment with this idea is the importance goal setting (Gist et al. 1990). Relevant goals intensify the learner’s interest in the tasks at hand, which results in persistence from the learner to reach the goal (Gist et al. 1990). In light of this, it is obvious that practical relevance of a training program has become a crucial factor entrenched in all research pertaining to transfer solutions. The archetype of any good workplace environment “provides adequate resources and opportunities to apply the new knowledge” (Liebermann & Hoffmann, 2008). To plow further into the idyllic environment of training practices is indispensable and should remain at the forefront of training practices research. SPONSOR TRAINING MAGAZINE EVENTS Need to Start (or Expand) a Corporate Coaching Program? Join Tim Hagan on September 29. Click here.

- 10. Check out the Top 10 Reasons Why You Should Attend the Allen Interactions User Conference in Chicago, Sept 22 Training's Live + Online has 4 NEW Certificate programs! Save $150 when you register a month in advance. Check out all our programs and NEW Website here. Download the brochure for the 2014 Online Learning Conference in Chicago, September 22-25. Going off- line to solve online challenges! Registration is open for the 38th Annual Training 2015 Conference & Expo, February 9-11, 2015, in Atlanta, GA! Interested in speaking at our Conferences? SPONSOR HOMEHOME CURRENT ISSUECURRENT ISSUE PAST ISSUESPAST ISSUES EVENTSEVENTS PRESENTATIONSPRESENTATIONS SUBSCRIBESUBSCRIBE WEBINARSWEBINARS TRAINING DAY BLOGTRAINING DAY BLOG

- 11. ENEWSLETTERENEWSLETTER FAQFAQ Page 1 of 3Transfer of Training: Moving Beyond the Barriers | Training Magazine 9/1/2014http://www.trainingmag.com/content/transfer-training- moving-beyond-barriers Researchers also have identified the organizational environment as a determinant of hindering transfer. The application of structured timely feedback in a positive environment is somewhat difficult to master. Unlike popular belief, extensive feedback is not the panacea of improved behavior. Rather, one must be vigilant when providing feedback (Van den Bossche, 2010). With careful consideration of these factors, feedback can be used as an effective support mechanism to assist in the transfer of training. Tips for Effective Transfer: A Proposed Model A new model of transfer has been offered in light of the difficulties outlined in past research (Burke & Hutchins, 2008). Based on the proposed model of transfer offered by the authors, here are some useful points to consider for promoting transfer: Extend stakeholders beyond trainers, trainees, and supervisors:

- 12. Although peer support has proven in the past to wield the effects of transfer on trainees, new research has shown peer support as being significantly influential on effects of transfer (Burke & Hutchins, 2008). Peer collaboration, networking, and the sharing of ideas relating to the content can act as support for skill transfer in trainees (Hawley and Barnard, 2005). Further, consider the organization itself as a major stakeholder. The organization’s “transfer climate” can directly influence training transfer results. Whether the organization values learning can have a direct impact on employee performance (Awoniyi et al. 2004). Extend beyond the classic before, during, and after evaluation of transfer: It is important to consider that transfer is not necessarily time-bound (Burke & Hutchins, 2008). “Put simply, the transfer problem is not rooted in a specific time phase and, thus, its remedies should not be either” (2008). Provide support for transfer throughout the duration of the transfer process and not solely at specific time phases. For example, consider creating jobs aids before the training so the trainee can use it during and after training. Such tactics help extend beyond the training itself and promotes for continuous on-the-job learning (Baldwin-Evans, 2006;

- 13. Clarke, 2004). Consider trainer characteristics and evaluation as influential factors: Learner characteristics, the design and delivery of the training, and the environment all have been considered as influential factors that may inhibit or support transfer. Consider incorporating expressions in the delivery of the content and ensure the content is well organized. Further, incorporate assessment of transfer from trainee, trainer, and the organization’s perspective. This helps to create an environment that values and supports learning (Bates, 2003). Include moderating variables: Consider the size (small, medium, large) of the organization. These factors may have a direct affect of the training department and the way in which transfer is evaluated (Burke & Hutchins, 2008). Although the ambition to create a perfect training transfer model is admirable, the fact remains that transfer is nothing short of complex. That said, in order to provide for optimal effectiveness of training for transfer, it is essential that all aspects of training be garnered into a manageable practice.

- 14. References Alexis Belair is a student at Concordia University in Montreal completing a Master’s degree in Educational Technology. SPONSOR FREE WHITE PAPERS Take the corporate MOOC PLUNGE! Transform training to learning - organizational learning in 5 manageable stages Virtual Onboarding for Today's Global Workforce MOST READ TODAY 1. Will that Visionary Plan Work? Better Check with the Board of Execution First (2,322) 2. Training Magazine Events (393) 3. Comrade or Competitor? Set the Tone When Onboarding (241) 4. Training Matters (220) 5. Four Types of Leaders (198)

- 15. Awoniyi, K., Salas, E., & Garofano, C. (2004). A study of best practices in training transfer and proposed model for transfer. In L. A. Burke & H. M. Hutchins (2008). Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(2), 107-128. Bates, R. A. (2003). A study of best practices in training transfer and proposed model for transfer. In L. A. Burke & H. M. Hutchins (2008). Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(2), 107- 128. Burke, L. A., & Hutchins, H. M. (2008). A study of best practices in training transfer and proposed model for transfer. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(2), 107-128. Cheng, E., & Hampson, I. (2008). Transfer and training: A review and new insights. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(4), 327-341. Gist, M., Bavetta, A., & Steven, C.K. (1990). Transfer training method: Its influence on skill

- 16. generalization, skill repetition, and performance level. Personnel Psychology, 43(3), 501. Hawley, J. D., & Barnard, J. K. (2005). A study of best practices in training transfer and proposed model for transfer. In L. A. Burke & H. M. Hutchins (2008). Human Resource Development Quarterly, 19(2), 107-128. Liebermann, S., & Hoffmann, S. (2008). The impact of practical relevance on training transfer: evidence from a service quality-training program for German bank clerks. International Journal of Training and Development, 12(2), 74-76. Randi, J., & Corno, L. (2007). Theory into practice: A matter of transfer. Theory into Practice, 46 (4), 334-342. Van de Bossche, P., Segers, M., & Jansen, N. (2010). Transfer of training: the role of feedback in supportive social networks. International Journal of Training and Development, 14(2), 81-94. Page 2 of 3Transfer of Training: Moving Beyond the Barriers | Training Magazine 9/1/2014http://www.trainingmag.com/content/transfer-training- moving-beyond-barriers

- 17. TRAINING TOP 125 2014 Training Top 125 Winners Operating like a well-oiled machine, No. FROM THE EDITOR Thanks for the Measurements, Don When I first joined Training magazine in 2007, my publisher gave me a stack of magazines to read and strongly suggested I familiarize myself with Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Evaluation. Leadership in Bloom Go Figure Lubed Up Weathering the Storm

- 18. Get Smart DIGITAL ISSUE Click above for Training Magazine's current digital issue Click here to subscribe! TRAINING LIVE + ONLINE CERTIFICATE PROGRAMS Now You Can Have Live Online Access to Training magazine's Most Popular Certificate Programs! Click here for more information. EMERGING TRAINING LEADERS 2014 Emerging Training Leaders Spring is—finally—in the air. 2013 Emerging Training Leaders By Lorri Freifeld

- 19. TWITTER Official Training Magazine Daily is out! …paper.li/TrainingMagUS/ Stories via [email protected] Training Magazine [email protected] Expand Official Training Magazine Daily is out! …paper.li/TrainingMagUS/ Stories via [email protected] Training Magazine [email protected] Expand 12h 31 Aug Tweets Follow Tweet to @TrainingMagUS FEATURED VIDEO

- 20. TRAINING MATTERSTRAINING MATTERSTRAINING MATTERSTRAINING MATTERS Posted: August 11, 2014 MORE RECENT VIDEOS Privacy Statement Terms of Use Drupal Themes by ThemeShark.com Page 3 of 3Transfer of Training: Moving Beyond the Barriers | Training Magazine 9/1/2014http://www.trainingmag.com/content/transfer-training- moving-beyond-barriers INFO LINE Tips, Tools, and Intelligence for Trainers Issue 0710 Training Basics Dennis E. Coates Enhance the Transfer of Training Issue 0710

- 21. A U T H O R Dennis E. Coates, Ph. D. Performance Support Systems, Inc. 435 Paradise Hills New Braunfels, TX 78132 Tel: 830.907.3000 Email: [email protected] Dr. Coates is CEO and co-founder of Performance Support Systems. He is the author of 20/20 Insight GOLD, a customizable multi-source performance feedback and survey technology. He has served on the faculties of the United States Military Academy, the Armed Forces Staff College, the College of William and Mary, and Thomas Nelson Community College, and as an adjunct instructor at the Center for Creative Leadership. He is the author of numer- ous articles on leadership, management, and training. Infoline Associate Editor Justin Brusino Copy Editor Ann Bruen Production Design Kathleen Schaner Enhance the Transfer of Training Training Basics

- 23. . Gain.Commitment.................................................................... .....................................11 Implement the Enhancements.......................................................................... .12 . Step.1..Integrate.Reinforcement................................................ ..................................12 . Step.2..Measure.Improvement................................................... ..................................12 . Step.3..Involve.Direct.Managers............................................... ...................................13 References & Resources................................................................................ .....14 Job Aid . Monitor.Key.Actions............................................................... ......................................15 Infoline.(ISSN.87559269).is.published.monthly.by.the.America n.Society.for.Training.&.Development,.1640.King.Street,.Alexa ndria,.VA.22314..The.subscription.rate.for.12.issues.is.$89.(for. ASTD.national.members).and.$129. (for.nonmembers)..Periodicals.postage.paid.at.Alexandria,.Virgi

- 24. nia..POSTMASTER:.Send.address.changes.to.Infoline,.P.O..Box .1443,.Alexandria,.VA.22313- 1443..Claims.for.replacement.of.subscription.issues.not.receive d. must.be.made.within.three.months.of.the.issue.date..Copyright. ©.October.2007.Infoline.and.ASTD..All.rights.reserved..No.part .of.this.work.covered.by.the.copyright.hereon.may.be.reproduce d.or.used.in.any.form.or.by.any. means— graphic,.electronic,.or.mechanical,.including.photocopying,.rec ording,.taping,.or.information.storage.and.retrieval.systems— without.the.express.written.permission.of.the.publisher..For.per mission.requests,.please. go.to.www.copyright.com,.or.contact.Copyright.Clearance.Cent er.(CCC),.222.Rosewood.Drive,.Danvers,.MA.01923.(telephone: .978.750.8500,.fax:.978.646.8600)..Material.appearing.on.pages .15-16.is.not.covered.by.the. copyright.and.may.be.reproduced.and.used.at.will. Need a trainer’s lifeline? Visit infoline.astd.org. Infoline. is. a. real. got-a-problem,. find-a-solution. publication.. Concise. and. practical,. Infoline. is. an.information.lifeline.written.specifically.for.trainers.and.other .workplace.learning.and.perfor- mance.professionals..Whether.the.subject.is.a.current.trend.in.th e.field,.or.tried-and-true.train- ing.basics,.Infoline.is.a.complete,.reliable.trainer’s.information. resource..Infoline.is.available.by. subscription.and.single.copy.purchase. Printed.in.the.United.States.of.America.

- 25. For.help.or.inquiries.about.your.subscription,.please.contact.Cu stomer.Care.at.1.800.628.2783/ 1.703.683.8100.(international). Copyright © ASTD � Not long ago, I asked a branch manager of one of the largest banks in the United States about the train- ing she had received during the past two years. In glowing terms she described a well-known effective- ness program. I asked, “Based on what you learned, how has your performance improved?” After a long pause, she replied, “It’s not that I’m doing anything differently, but I really enjoyed that course.” No matter how excellent the instruction is, it’s rare to find people who are consistently applying what they learned in training. Organizations spend bil- lions of dollars each year on training programs, expecting to achieve lasting, measurable improve- ments in performance and positive impacts on busi- ness results—a goal that is hard to achieve. Published research confirms that only a small per- centage of the participants of training programs actually change their behavior. Experts have been telling us this for decades. They estimate that most of this investment—between 70 and 90 percent—is wasted. Cognitive neuroscience explains that changes in behavior require repetition of new behaviors to develop new connections in the brain. This pro-

- 26. cess takes a lot more time than a typical training program allows. When participants first return to the workplace, their new skills feel forced and awk- ward, and they don’t consistently yield the desired results. Without a supportive environment, many people give in to the pressures of work and fall back on their old habits. Recent books address what they refer to as the “transfer of training” problem. The issue, they say, is not with the trainers or their programs, but with the fact that learning is an ongoing process, not an event. A finite number of days of instruction simply can’t be expected to undo problem behavior pat- terns that have been ingrained for years. Experts claim that most organizations fail to follow through with enough reinforcement for individuals to in- grain the new skills they learned in the classroom. The purpose of this Infoline is to help you achieve what many regard as the “holy grail of human resource development (HRD)”—permanent, measurable improvements in performance and a positive impact on business outcomes. The approach is to focus on the specific areas of train- ing and development that most organizations fail to do well and to suggest practical strategies for achieving this highly desirable and elusive goal. This Infoline builds on the work of previous Infolines No. 9512, “Transfer of Training,” and No. 9804, “The Transfer of Skills Training,” to provide new insights and describe specific actions you can take to improve your organization’s current system. It includes a realistic plan for getting change un- der way—to create a foundation of initial successes

- 27. from which an organization can continue to get bet- ter results going forward. Learning Transfer � Enhance the Transfer of Training � Answering the following seven questions will help you establish a “direct line-of-sight” from the desired business results to the developmental program: 1. Which business results are not being met? 2. Which work units are assigned to contribute to these results? 3. Which unit performances are falling short of expectations? 4. Which areas of individual performance are con- tributing to this unit failure? 5. Which individual performers aren’t measuring up in these areas? 6. Are the performance shortfalls due to deficien- cies in knowledge or skill? 7. If so, what kind of developmental program would best correct these deficiencies?

- 28. With regard to Question 6, remember that individ- ual performance shortfalls do not necessarily mean that employees need training. They may already know how to do what they’re expected to do, but they may not have the requisite motivation or sup- port from the organization to do their jobs. Set Up Training Transfer The reinforcement of new behavior patterns has to begin in the classroom. The first step in improv- ing performance is to introduce a model of the desired behavior. The classroom is ideally suited for this task. Over the years, training professionals have adopted a number of adult learning methods that promote retention and learning transfer. To learn more, see the sidebar Training Design Strategies. The more of these elements you employ in your develop- ment programs, the better participants will be pre- pared for what comes afterward—the difficulties of applying, reinforcing, and ingraining new work habits. Classroom instruction can prepare learners to work through these challenges, and it can intro- duce them to resources and programs that support ongoing learning. Copyright © ASTD� Enhance Training Transfer � Enhance the Transfer of Training

- 29. � What’s needed in most organizations is not so much a revamping of the existing training and develop- ment system as optimization of current practices. Therefore, this Infoline will focus on eight initia- tives to increase the successful transfer of training: l Focus on shortcomings: Identify training needs that will have a positive impact on business results. l Set up training transfer: Incorporate learning strategies that promote application and rein- forcement of skills. l Coordinate learning networks: Organize support for reinforcement. l Prepare coaches: Get direct managers ready for their developmental role. l Integrate follow-up: Implement reinforcement programs with assessment and training programs. l Insist on accountability: Measure performance improvement and calculate ROI (return-on- investment). l Align culture: Modify the organization’s policies and practices to support performance improve- ment. l Gain commitment: Support follow-up reinforce- ment.

- 30. By focusing on these eight initiatives you can drive the transfer of training in your organization. Focus on Shortcomings If you want training to have a positive impact on business results, your training programs must focus on correcting performance shortfalls that negatively affect business. Take an active role in identifying these shortcomings with department managers. Copyright © ASTD � Enhance the Transfer of Training � Training Design Strategies The following is a collection of widely used training design best practices that support follow-up reinforcement and long-term ingraining of desired skills and work habits. l Create or acquire courses to address performance prob- lems that have an impact on business results. l Create course objectives that are application oriented— what participants will need to do on the job. l Design the course to focus on doing a few important things very well rather than covering all possible topics. l Structure the course so that the learning is broken into

- 31. short segments. l Explain why the training is being conducted—the need for the organization to improve business results, evidence of related knowledge and skill deficiencies, or the impact of new skills on workplace performance and business results. l Help learners understand the personal benefits of the learning—“what’s in it for them.” l Early in the course, brainstorm with learners to focus on workplace challenges, and then refer to these scenarios during course activities. l During instruction, relate new concepts and skills to what learners already know. l Provide forms and build in opportunities for learners to record ideas, insights, and post-course application issues—questions, possible problems, and resources they’ll need to put skills into practice. l Provide frequent opportunities to discuss “lessons learned.” l Make practice exercises as realistic and work-related as possible. l Give learners a variety of case studies and relevant articles. l Vary the practice exercises—challenge learners with dif- ferent situations and scenarios. l Vary the membership of table groups, so learners are

- 32. exposed to different perspectives. l Give immediate individual behavioral feedback during practice exercises. l Structure practice so that learners can give one another feedback. l Give learners structured time to visualize correct perfor- mance on the job. l Give learners job aids related to major skill areas— summary references that describe how-to steps. l Preview support for post-course follow-up reinforce- ment: reinforcement planning, online resources, work- books, job aids, feedback assessments, learning support groups, and direct manager coaching. l Help learners identify individuals for a learning support group—people who can give feedback, encouragement, and advice or coaching after the course. l Make time for learners to discuss their concerns and plans for using their new skills. l Have learners draft a realistic plan or contract for using their new skills on the job; make copies—send to direct managers, and several weeks after the course, send to participants as a reminder. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training

- 33. � The stakes are too high to simply hope that partici- pants will follow through on their own. There are many ways to structure learning support using a va- riety of media, formats, frequency, and participants. The smart money is to find out from learners and their direct managers what they need, offer sugges- tions, and create a plan to make it happen. Prepare Coaches Management may be willing to invest in profes- sional coaches for executives, but coaching for the majority of employees must come from within the organization. Trainers often have good coach- ing skills, but they’re usually busy preparing and delivering programs. In addition, there aren’t enough trainers to go around. Mentors are a pos- sible coaching resource, but most employees don’t have a mentor, and mentors lack oversight and authority. n UnderstandingManagement’sRole Although trainers provide learning opportunities and support, what managers do after training influ- ences behavior far more than what trainers do in the classroom. The manager is responsible for directing, motivating, observing, evaluating, and improving the employee’s performance and has the authority to tell employees what to do. The manager decides whether an employee will even have the opportu- nity to use newly learned skills. How well a manager carries out this role can make or break the transfer of new knowledge into permanent improvements in

- 34. workplace performance. This fact is not intended to devalue the vital role of trainers. However, trainers don’t own the system, and they don’t run the organization. Once program participants leave the classroom, trainers can no longer significantly influence their development. Trainers have some influence, but have practically no control over what happens in the workplace, where new skills must be diligently applied in or- der to be ingrained. To learn more about the role of managers in training reinforcement, see the sidebar Learning Triangle. Also, the trainer’s influence isn’t confined to the classroom. The next critical area describes how trainers can support learners and their direct man- agers after formal instruction is over. Coordinate Learning Networks While only the direct manager can provide effec- tive performance coaching in the workplace, he or she can be supported in this role. For one thing, trainers are uniquely qualified to get involved in follow-up reinforcement. Also, other interested individuals within an organization can give a devel- oping employee advice, feedback, encouragement, and coaching during the extended period of rein- forcement. Your learning network should include l program co-participants l peers l co-workers l subordinate team members l mentors.

- 35. These adjunct coaches represent a network of sup- port for the learner. If trainers simply encourage participants to create their own networks, results will vary widely. A more effective course is to plan and set up a system to support learning networks, tell participants and their bosses how to use it, and supervise its use. Here are some of the approaches used by successful organizations: l “brown bag” or informal roundtable lunch meet- ings, during which participants review learning media, discuss on-the-job challenges, and share experiences l webinars or teleconferences, in which trainers or guest speakers discuss performance topics with participants l online forums, in which participants interact with supportive individuals to ask questions, discuss issues, get feedback, or share encouragement l action plan monitoring systems, whether an on- line service or a manual tickler system managed by trainers. n ChangingMindsets For many organizations, the biggest hurdle is to change the mindsets of managers. Managers who already have more to do than they can accomplish will probably resist the idea of assuming what they perceive as “new responsibilities.” The notion that the most crucial phase of learning begins after class-

- 36. room instruction is over is alien to many workplaces. Many managers exhibit these negative behaviors: l showing reluctance to release employees for training l contacting participants during the course—or even worse, calling them away from classroom activities l expecting employees to “get back to work” l creating an environment of business as usual and not giving employees a chance to apply the new skills l misunderstanding what’s involved in skill devel- opment and the essential role of the manager in reinforcing new skills. n PreparingManagers You can help overcome the reluctance of direct managers to accept their coaching role by com- municating clear expectations. Ideally, coaching and developing direct reports will become formal aspects of a manager’s responsibilities. These ex- pectations can be incorporated into manager com- petencies, leadership assessments, job descriptions, performance review parameters, roles and func- tions manuals, and other administrative documents. For help establishing expectations, see the sidebar Manager’s Leadership Checklist. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training

- 37. � Performance improvement must be an ongoing process in which three key influencers—trainers, learners, and learners’ manag- ers—cooperate to promote employee development as an aspect of everyday work. This partnership is visualized as a “learning triangle.” When managers aren’t involved, program participants are left without the support, encouragement, and coaching they need to persist during the challenging period of reinforcement. This shortfall is the norm in most organizations, which in large part explains why training so often fails to transfer to improved on- the- job performance. Learning Triangle Direct Manager TrainerLearner Assessment Training Reinforcement Monitoring and encouraging improved perfor- mance may be a vital leadership role, but many managers feel unprepared for it. If managers haven’t previously been expected to take respon- sibility for the day-to-day development of subor-

- 38. dinates, look for off-the-shelf coaching courses to fill this need. The most effective courses will give a realistic explanation of what it takes to change be- havior, as well as the manager’s responsibilities for coaching and improving performance. Also, nearly every manager needs practice in facilitating one- on-one discussions with subordinates to help them learn from both success and shortfall experiences. To learn more, see the sidebar Seize the Coaching Moment. Integrate Follow-Up To expect improved performance from an isolated training event defies everything we know about be- havior change. To achieve lasting changes in behav- ior, organizations need to take a different approach. Developmental programs need to be preceded by assessment and followed by an extended period of reinforcement, which includes l ongoing learning l coaching l follow-up assessment l accountability. These activities should be conceived and presented as a single, integrated process. Integrated training materials need to include the resources that will be used during reinforcement and instructions about how to use them. Also, the training programs need to be selected based on pre-course assessment, and instructors should refer to these assessments dur- ing the course. This means that specific behavioral training objectives need to be identical to the be- havioral items assessed before and after training.

- 39. These assessments are important, and you can use them later to calculate ROI. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training � Use this checklist to inform, instruct, empower, assess, and hold managers accountable for their responsibilities in coaching and developing direct reports in the workplace. h Communicate with trainers about direct reports’ perfor- mance, participation in developmental programs, and rein- forcement activities. h Attend, audit, or review direct reports’ courses to prepare for setting an example of the skills to be learned; if this is not pos- sible, review course materials including agendas and learning objectives. h Meet with direct reports to evaluate performance assessment results and communicate expectations for performance im- provement. h During training, refrain from contacting direct reports about work issues. h After training, meet with direct reports to evaluate learning experiences, set performance improvement goals, and plan for ongoing reinforcement. h Give assignments that require using new skills on the job. h Provide encouragement.

- 40. h Discuss “coaching moments” with direct reports—help them integrate the lessons of experience while applying new skills. h Give direct reports time to meet with trainers, co- participants, mentors, and others who can contribute to learning. h Meet with direct reports to review the results of post- course feedback surveys and update plans for ongoing reinforcement. h Hold self and direct reports accountable for achieving perfor- mance improvement goals. Manager’s Leadership Checklist Assessing Interpersonal Skills Performance tests are a straightforward assess- ment method for most technical and administra- tive skill areas. However, most jobs also involve interpersonal skills that can be hard to measure. These skills include l team communication l leadership l sales l instruction l negotiation. The most effective method of assessing interper- sonal behaviors is multi-source feedback, in which participants receive information about their perfor-

- 41. mance from the people who work around them. To create tailored assessments that are aligned with what actually happens in the workplace and with course objectives, an organization needs to use a highly customizable survey technology. Also, to support post-course measurement, the system will need to enable low-cost repeat assessments. Insist on Accountability Like an investment in new equipment, technol- ogy, or advertising, it’s fair that executives ex- pect their considerable investment in training and development programs to produce tangible, measurable results. To gain their support for fu- ture developmental programs, trainers need to provide credible proof of improved performance and return-on-investment. n IndividualPerfomanceROI Rather than pursue “business results ROI,” which is the quest to isolate the impact of training among many other contributing factors, focus on an “in- dividual performance ROI,” the financial return you get from actual improvements in performance. This technique addresses the two questions of most interest to executives: 1. Did the training work—did people improve their performance? 2. Was the investment worth it—did these im- provements outweigh the costs? Copyright © ASTD

- 42. Enhance the Transfer of Training � A coaching moment occurs whenever someone applies a new skill in the workplace, so recognizing this moment is particularly important for direct managers. The purpose of engaging an em- ployee in a discussion about a workplace experience is to help the individual learn from the event, whether it be a success or a shortfall. When a manager learns that a direct report has had an opportu- nity to apply a new skill, he or she should encourage the individual to talk about the experience. Carefully avoiding an instructional approach, the manager should guide the employee to think about what happened by asking leading questions such as the ones listed below. Using these open-ended questions as a guide, the skillful coach can encourage the learner to do most of the talking: l What happened? Who did what? What was the sequence of events? l Why did you handle it that way? What were you trying to accomplish? What helped or hindered? What led to the ulti- mate outcome? l What were the consequences? What was the impact on others? What were the costs and benefits? Was anything resolved? Did the incident cause any problems? l What did you learn from this? What would you do differently if you encountered a similar situation in the future?

- 43. l What are your next steps? What support do you need from me to be more successful? A typical discussion may last only a few minutes but needs to be long enough to help the direct report to “connect the dots” and integrate the learning. Seize the Coaching Moment Performing dollar calculations for this type of ROI is relatively simple. The key is to quantify the ac- tual improvement in performance, then translate this benefit into dollars and determine whether the payoff is more than the cost. Conveniently, the data created by the pre- and post-course performance assessment comparison technique described above can be used in a simple return-on-investment cal- culation. See the sidebar Measure Performance ROI for the sample calculation. Executives should find that this calculation provides meaningful evidence of results, and they should have no difficulty understanding how it was de- rived. Note that the sample calculation presented in the sidebar is based only on the first post-training measurement. If coaching, learning, feedback, and accountability continue as a routine aspect of work, the results of subsequent assessments may improve again going forward, causing the benefits and ROI to increase even further. Once again, the performance data used in this cal-

- 44. culation comes from the feedback assessments. A multi-source feedback survey includes the behav- iors to be taught in training. Managers tell direct reports that the survey will be administered again after training. The pre-course diagnostic helps participants set quantified, behavior-based perfor- mance improvement goals. Knowing that follow-up measurements will be taken later peaks their moti- vation and attention going into training. n WhentoEvaluate It’s important not to measure post-program perfor- mance improvement too soon. It usually takes time for an individual to show improvement and mastery. Even in the best case, early attempts are awkward and results will be mixed. If surveys are conducted too soon, while learners are still struggling to mas- ter the skills and unlearn old habits, performance scores could actually drop, introducing the possibil- ity that measurements could be misinterpreted. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training � Individual performance ROI is obtained using this formula: Percent ROI 5 (Program Benefit – Program Costs) 3 100 4 Program Costs To estimate the costs of an individual’s training, add the program costs for trainers, assessments, materials, facilities, and time away

- 45. from work, and then divide by the number of participants. In this example, assume the cost of an individual’s attendance at a three- day course was $1,600. When calculating the benefit of the training, the question is how much additional productivity will an organization get for the same salary? You’ll need to know the individual’s total annual compen- sation, data showing how much the individual’s performance has improved, and an estimate of how much the individual’s perfor- mance affects his or her productivity. Assume the learner’s total annual compensation was $75,000. Sev- eral weeks before the training, the participant received a bench- mark diagnostic multi-source feedback assessment. To measure performance improvement, the same assessment was adminis- tered nine months after the course. The assessment scores (scale 0 to 10) increased from an average of 6.3 (before training) to 7.9 (after training). (7.9 – 6.3) 4 6.3 5 25 percent improvement in performance Individual performance is only one of several productivity factors. Support, co-worker skills, reward systems, and many other factors also have an impact on productivity. Sorting this out scientifically is impractical and unnecessary. Simply ask managers to agree on

- 46. a consensus estimate of the relative impact of an individual’s per- formance on his or her productivity. In this case, management estimated that the impact was approximately 33 percent. Multiply the annual compensation times the percent improvement in per- formance times the percent of impact on performance and you will get the dollar value of the improved individual performance. $75,000 3 25 percent 3 33 percent 5 $6,250 additional impact on productivity This benefit is significantly greater than the total cost of the indi- vidual’s training, which was $1,600. Percent ROI 5 ($6,250 – $1,600) 3 100 4 $1,600 5 290 percent Measure Performance ROI A good time to administer your initial assessment is six to nine months after training. This gives learn- ers quantitative and qualitative feedback about how they’re doing as they try to improve their skills. Also, the assessment documents whether the individual has improved on-the-job performance. Since both pre-course and follow-up post-course assessments are identical, scores can be compared easily. Im- proved scores confirm improved performance. For ongoing measures of performance improvement, simply administer the assessment again at the 12- and 18-month marks.

- 47. n OtherConsiderations Evaluating behavior (Level 3) and measuring re- sults (Level 4) produce hard evidence of whether programs are changing behavior. While Donald Kirkpatrick’s model is often used to hold the train- ing department accountable, it’s important to re- member that others share responsibility for these results: l learners, who persist during the lengthy and sometimes frustrating period of reinforcement l direct managers, who supervise and coach the learner while providing opportunities to apply skills in an encouraging environment l trainers, who present behavior-based training that is optimized for skill transfer and who coor- dinate follow-up programs l senior executives, who establish expectations, commit resources, promote an approach that can change behavior, and remain patient while employees ingrain new behavior patterns. Align Culture Aspects of an organization’s culture, policies, and systems may frustrate participants’ efforts to ap- ply what they’ve learned. There are many possible problems, such as project assignments that prevent application of new skills or incentives that fail to encourage desired performance. There are many possible issues, and most of the time they are aspects of the culture that have persisted and are

- 48. now causing problems. If the work environment thwarts the application of new skills, there’s little chance that learners will persist through the diffi- cult period of reinforcement. Locating Barriers What aspects of an organization’s culture have an impact on the transfer of training? What can be done to optimize the system for performance im- provement? In order for management to remove barriers in the workplace, it needs to locate them. This isn’t an easy task, because problem policies and practices serve important purposes and have usually been in place a long time. Both managers and trainers are adept at sensing what’s going on in the workplace, and they can report problems to management. Perhaps the easiest way to identify these issues is to get feedback from the participants themselves after training. See the sidebar Gauge Organiza- tional Support for Performance Improvement to learn more. Ideally, the survey is administered to program participants 30-60 days after they return to the workplace, when they’ve had time to apply their skills. The survey solicits ratings and com- ments about the most important aspects of orga- nizational support for performance improvement. When enough responses have been collected, man- agement can study the consolidated feedback and modify policies and practices accordingly. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training

- 49. � Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training �0 Gauge Organizational Support for Performance Improvement Use this survey to assess how well organizational systems support an employee’s efforts to improve performance. For maxi- mum effectiveness, survey learning program participants 30-60 days after they return to the workplace. How strongly do you agree with the following statements? (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) ______ My job responsibilities require me to use the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My performance goals and objectives require me to use the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ I’ve been given assignments or tasks with opportunities to apply the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My performance review evaluates how well I’m using the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ The rewards and incentives available to me motivate me to use the skills and concepts I learned in training.

- 50. ______ Additional learning resources such as programs, videos, and books are available to help me improve how I per- form the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ I have regular opportunities to learn from others, to talk with co-workers, program participants, or mentors about “lessons learned” related to the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ Management has made it clear that I’m expected to use the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ I receive feedback from surveys that measure how much I’ve improved the way I perform the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My manager sets a good example for using the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My manager has told me that I’ll be held accountable for using the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My manager is actively involved in my ongoing learning and development related to the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ The way my manager coaches me in the workplace helps me improve the way I perform the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My department structure makes it easy for me to apply the skills and concepts I learned in training. ______ My organization’s policies and practices encourage me to apply the skills and concepts I learned in training.

- 51. ______ My organization gives me adequate support to help me improve the skills and concepts I learned in training. Over a period of time, executives and supervi- sors alike can get used to the status quo. Like the proverbial frog in a pot of slowly warming water, people may not sense the problem. They have be- come comfortable with a bad situation that will eventually cause unacceptable pain. Executives need to confront this mindset before more dam- age is done. No organization wants to waste money, and while optimizing development programs can produce long-term improvements in performance and a significant return-on-investment, people may be reluctant to do things differently. Without com- mitment at all levels of management, the will to push past resistance simply won’t be there. Tough decisions will not be made, and initiatives will be abandoned. n Top-LevelCommitment It can be challenging to gain attention, commit- ment, and action from top-level management. They may operate several layers of management removed from training and development programs. They may be preoccupied with shareholder, strategic, legal, acquisition, or succession issues and have little time for focusing on training and development. But if management doesn’t make a priority of improv- ing performance and optimizing systems to support transfer of training, nothing is likely to change. The requisite level of commitment usually builds because top executives notice compelling business

- 52. reasons for getting behind the changes. Like any major investment in infrastructure, training and development is expensive, and executives should expect measurable results. Key executives who have ownership interest or profit-and-loss respon- sibility will be especially concerned if resources are being wasted. Commitment is usually sparked by a knowledge- able champion who owns responsibility for training and performance improvement, understands the issues, and wants to do something about them. After gathering data about program costs and pro- gram results, this influential person can educate key executives and gain their commitment up front. Gain Commitment You may find that your organization is already do- ing much of what is recommended here. However, optimizing an approach to training and develop- ment typically means making changes. Be prepared for the training staff and managers to resist, even if the changes make sense and promise to increase profitability. For example, it’s natural that some managers may not want to take on what they perceive as additional responsibilities, especially if these duties involve knowledge and skills they don’t have. Program par- ticipants may feel uneasy about being assessed be- fore and after training, because this enables their managers to hold them accountable for results. The trainers themselves may feel uneasy about assessments that accurately measure whether their programs actually change behavior. Popular train-

- 53. ing programs may be eliminated as irrelevant. New technologies may be acquired. Long-standing poli- cies and procedures may have to change. n BeaChangeAgent Change agents can run into a wall of denial. Often an organization has lived with pain of this kind of waste so long that it’s perceived as normal. Peo- ple rationalize that if world-class trainers present high-quality courses, some good has to be com- ing from these activities, even though behavior doesn’t appear to change. Here are some common rationalizations: l It’s unreasonable to expect measurable improve- ments in performance. l Improvements are too subtle to notice. l Improved behavior will manifest itself unpre- dictably in the future. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training �� Copyright © ASTD�� Top-down commitment needs to be visible and demonstrative. Executives need to l make sure managers understand why a rein-

- 54. forcement-intensive approach is necessary and why the organization must take new approaches to performance improvement l communicate to managers that they are expected to function effectively as performance coaches for their direct reports, and if needed, give them training to prepare them for this role l improve aspects of policies and practices when it’s discovered that the system discourages on- the-job application of newly learned concepts and skills l clarify expectations for improved performance and positive impacts on business results, to in- clude measuring performance improvement, calculating ROI, and defining accountability l acquire compatible behavior-based programs that work together seamlessly to support assess- ment, training, and reinforcement. Executives have several options for getting their message across: l meetings and briefings l presentations by experts l repeating the message in a variety of media: email, web, video, newsletters, and memoranda l workshops to involve managers in optimizing the organization’s approach to training and develop- ment and creating a plan for implementation

- 55. l detailed expectations incorporated into manag- ers’ job descriptions and performance reviews l personal appearances in courses to emphasize importance l setting an example by modeling the desired skills. Enhance the Transfer of Training �� Implement the Enhancements Practically speaking, it’s easier to gain commitment if management understands that it doesn’t have to implement all eight critical enhancements at once to be successful. While many variables influ- ence whether classroom learning is reinforced and ingrained in the workplace, it’s possible to make a beginning and get positive results by focusing on three of the critical enhancements. Step 1. Integrate Reinforcement Start small, and begin with a single program. You should acquire or design a training program that l is structured to achieve specific behavioral objectives l includes resources, such as related job aids, books, and behavior model videos, which can be used to reinforce skills after training.

- 56. Next, set up a system to assess current skill levels of the program’s behavioral objectives, through obser- vation, performance testing, or multi-rater assess- ment. If the latter, make sure the feedback system is easily customizable and can be repeatedly used with various subjects at minimal expense. Step 2. Measure Improvement Assess performance levels about a month before and again several months after training. Make sure participants know about the assessment schedule in advance. Coach managers to help direct reports analyze the results of the assessment in order to focus on priority learning goals during the course. After the course, assess performance again using the same behavior sets. Then compare pre-course scores with post-course scores; the quantitative and qualitative data will reveal whether areas of perfor- mance have improved. Notify learners and direct managers about whether ongoing reinforcement has had the desired effect; then they can use the results to establish a new set of developmental goals and metrics. Copyright © ASTD Enhance the Transfer of Training �� Measuring performance improvement provides

- 57. hard evidence of whether programs are changing behavior, making it possible to hold the key players in the “learning triangle” accountable: l learners, who must make a determined effort to change behavior patterns l direct managers, who monitor and coach the direct reports l trainers, who present behavior-based training that is optimized for skill transfer. Step 3. Involve Direct Managers Changing behavior patterns takes months, not days—even in ideal circumstances. Only the learn- er’s direct manager is in a position to give enough support, oversight, encouragement, feedback, coaching, and reinforcement over the long term to change behavior. No matter how much was invested in the learning program, how well the manager car- ries out this role will make or break the transfer of new knowledge and skills into permanent improve- ments in workplace performance. At a minimum, you’ll need to do three things to draw direct managers into a “learning triangle” with their direct reports and trainers: 1. Inform managers of their developmental re- sponsibilities. Have them review the sidebar Manager’s Leadership Checklist, and then let them know they will be held accountable for those actions.

- 58. 2. Prepare direct managers to be more effective performance coaches. If needed, make coach- ing training available. At a minimum, give them a book about coaching for managers. 3. Hold managers accountable for carrying out their role as performance coaches. Define ex- pectations in job descriptions and performance evaluation systems. Using this simplified strategy for getting started will immediately enrich the way you conduct training programs, and you will experience positive results. However, it’s only a beginning. Each of the eight critical areas deals with significant cause-and-effect shortfalls and opportunities, none of which should be ignored. Your organization will need to build on the foundation of initial successes with a tailored strategy to optimize the other key areas that influ- ence learning transfer. The transfer of training issue has always been the human resource development community’s biggest problem and biggest opportunity. If applied, this summary of how skills are ingrained and practical methods for transferring classroom instruction to improved workplace performance can help you cre- ate a huge success story in your organization. See the job aid Monitor Key Actions. Obviously, there’s no quick fix. In most organiza- tions, a lot of work will need to be done. How far you go to create lasting improvements in performance and positive impacts on business outcomes will depend on the degree to which you and manage- ment acknowledge the pain that comes from com-

- 59. mitting resources to programs that fail to achieve the expected results. Copyright © ASTD�� Enhance the Transfer of Training Baldwin, Tim, and Kevin Ford. “Transfer of Training: A Review and Directions for Future Research.” Personnel Psychol- ogy, May 1982, pp. 63-105. Kandel, Eric R., and Robert D. Hawkins. “The Biological Basis of Learning and Individuality.” Scientific American, September 1992, pp. 79-86. Newstrom, John W. “The Management of Unlearning: Exploding the ‘Clean Slate’ Fallacy.” Training and Development Journal, August 1983, pp. 36-39. Saari, Lise M., et al. “A Survey of Manage- ment Training and Education Practices in U.S. Companies.” Personnel Psychol- ogy, April 1988, pp. 731-743. Zenger, Jack, Joe Folkman, and Robert Sherwin. “The Promise of Phase 3.” T+D, January 2005, pp. 30-34. Books Begley, Sharon. Train Your Mind, Change

- 60. Your Brain: How a New Science Reveals Our Extraordinary Potential to Trans- form Ourselves. New York: Ballantine, 2007. Brinkerhoff, Robert O., and Anne M. Apk- ing. High Impact Learning: Strategies for Leveraging Business Results from Training. New York: Basic Books, 2001. Broad, Mary L. Beyond Transfer of Train- ing: Engaging Systems to Improve Per- formance. San Francisco: Pfeiffer, 2005. Broad, Mary L., and John W. Newstrom. Transfer of Training: Action-Packed Strategies to Ensure High Payoff from Training Investments. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1992. Kirkpatrick, Donald L., and James D. Kirkpatrick. Transferring Learning to Behavior: Using the Four Levels to Improve Performance. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2005. Leberman, Sarah, Lex McDonald, and Stephanie Doyle. The Transfer of Learning: Participants’ Perspectives of Adult Education and Training. Burling- ton, VT: Gower Publishing, 2006. Luecke, Richard. Coaching and Mentoring: How to Develop Top Talent and Achieve Stronger Performance. Boston: Harvard Business School, 2004.

- 61. Mager, Richard F., and Peter Pipe. Analyz- ing Performance Problems: Or, You Really Oughta Wanna, 3rd ed. Atlanta: Center for Effective Performance, 1997. Phillips, Jack J. Return on Investment in Training and Performance Improvement Programs. Houston: Gulf Publishing, 1997. Phillips, Jack J. and Mary L. Broad, eds. Transferring Learning to the Workplace: Seventeen Case Studies from the Real World of Training. Alexandria, VA: ASTD, 1997. Robinson, Dana Gaines, and James C. Robinson. Performance Consulting. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 1996. Sousa, David A. How the Brain Learns, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2000. Whitmore, John. Coaching for Perfor- mance: Growing People, Performance and Purpose, 3rd ed. London: Nicholas Brealy, 2002. Wick, Calhoun, et al. The Six Disciplines of Breakthrough Learning: How to Turn Training and Development into Business Results. San Francisco: Pfeiffer, 2006. Infoline s

- 62. Garavaglia, Paul L. “Transfer of Training.” No. 259512 (revised 2000). Sullivan, Richard L. “The Transfer of Skills Training.” No. 259804. References & Resources Articles Lynn S. Lewis, MBA, PMP, CPLP President Learning Solution s, LLC External Consultant Enhance the Transfer of Training To ensure that training produces permanent, measurable results in the workplace, key participates should be monitored before, during, and after training has occurred. Use this checklist to plan, track, and evaluate actions of key role players: trainers,

- 63. learn- ers, and direct managers. Monitor Key Actions (Continued on next page) The material appearing on this page is not covered by copyright and may be reproduced at will. �� Job Aid Before Training This time should be used to assess current skills and prepare for the upcoming training. Trainers h Acquire, design, or review and update courses to ensure they incorporate learning strategies that promote reten- tion and learning transfer. h Send managers and learners information about pre- course benchmark individual diagnostic surveys.

- 64. h Administer pre-course individual benchmark diagnostic surveys and send confidential reports to participants (com- plete feedback) and their direct managers (summary). h Distribute pre-course learning materials to participants and course information to learners’ direct managers, in- cluding performance improvement and business results objectives, course content, and schedule. Managers h Review course materials and meet with direct reports to discuss forthcoming training programs: benchmark diagnostic scores, developmental priorities, relevance to workplace shortfalls, impact on business results, course content, boss’s support role, arrangements to cover re- sponsibilities, expectations, post-course reinforcement planning, and assessment activities. h Meet with direct reports to discuss forthcoming bench- mark diagnostic survey: what, why, who, when, how. h Review, audit, or attend the course to prepare for setting a positive example.

- 65. Learners h Complete pre-course assignments, focusing on personal learning and performance improvement goals. During Training It’s important that the learners receive support while they are in training; also, they should be prepared for reinforcement. Trainers h Facilitate programs, implementing training strategies that promote retention and learning transfer. h Brief learners about follow-up learning resources and help them set up learning support networks. Managers h Take care of learners’ responsibilities and protect partici- pants from work-related issues. Learners

- 66. h Focus on priority goals for improving performance, participate in skill-building exercises, and make plans for follow-up application and reinforcement. After Training This time should be used to reinforce skills and ensure that learners are able to apply their new skills on the job. Trainers h Publicize and recognize successful course completion. h Make online behavior-modeling videos and other learn- ing resources available to participants. h Host “brown-bag” learning lunches and other discussion groups. h Administer brief feedback projects when participants want anonymous, ongoing feedback from team members.

- 67. The material appearing on this page is not covered by copyright and may be reproduced at will.�� Enhance the Transfer of Training Job Aid Monitoring Key Actions (continued) After Training (continued) Trainers (continued) h Assist in calculating return-on-investment. h Administer a repeat post-course individual skills assess- ment and send results to learners (complete feedback) and learners’ managers (summary). Managers h Meet with learners to discuss the course experience, set goals, and plan for applying and reinforcing new skills. h Set an example for desired behavior.

- 68. h Provide projects, assignments, and other opportunities to apply newly learned skills. h Monitor workplace performance, give feedback, and offer encouragement, as appropriate. h Meet with direct reports to discuss successes and frustra- tions and to help them learn from work experiences. h Meet with direct reports to compare pre-course and post-course feedback assessment results, update per- formance improvement goals, and adjust plans for follow-up reinforcement. h Exercise patience as they await evidence of improved performance and positive impacts on business results. Learners h Brief team members about course objectives and content, major lessons learned, and plans for follow-up reinforce- ment as well as request ongoing feedback and support. h Complete a survey about the organization’s support for

- 69. performance improvement, one to two months after the program. h Stay in contact with trainers, course participants, and mentors, who share experiences, insights, feedback, and encouragement. 250710. $12.00.(USA) STRATEGY | 04 | DEC 13 | TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT www.aitd.com.au We train people so they will learn. The reason we want people to learn is so they will change a behaviour or perform a certain way. Surprisingly, little emphasis is placed on

- 70. ensuring learning occurs in the training and even more surprisingly, little importance is placed on making sure learning transfers across to improve performance on the job. Is there a missing link somewhere between the conception of the training idea, the delivery of the training intervention and the return back to work? Without a platform or a process to help recently trained employees actually apply their new learning at work, the money spent on the training is wasted. The transfer of learning to the workplace is critical and yet it is often totally disregarded. The link to performance improvement is nowhere to be seen. Think of how many courses you or your colleagues have completed after which you have had every intention of using the new skills or knowledge, only to find you never quite get around to it. You still have the binder or the notes or the thoughts but, alas, you do nothing with them. There are numerous obstacles that marginalise the transfer of learning for newly

- 71. trained employees. Even though participants finished the training ready to change, in many instances it is easier to revert back to the old way when they get back to their roles. And…there is usually no consequence for doing so except, perhaps, to be signed up to the same course next year. “Bandaid” solutions are prevalent in many places - train them, test them and set them free: a quick recipe for an ineffective training strategy that ultimately wastes the precious resource of time and we all know time costs money. Quality learning comes from top notch training that is designed to meet organisational goals and to produce measurable results. Measuring learning is a skill and must reflect the level of complexity that is required to help the employee transfer the skills and knowledge to their role. Transferring Learning

- 72. Let’s assume the training was excellent and the learning was measured. What structure is in place to help the employee transfer that learning to their job? More importantly, who is responsible for this, and, what role do managers play? The workplace climate can greatly affect the transfer of learning. If staff are dismissive about training, trainers are poorly respected, or topics are seen as irrelevant, this inspires no confidence or desire on the part of the learner to actually apply their learning at work. There are numerous things that can be done to promote a better learning culture and the responsibility of this does not fall with one person. If a learner returns to work to find all their colleagues using the old method or the wrong method, the learner is unlikely to be the odd one out by using a different process. It is disheartening and alarming for newly trained employees to do a task the way they have been trained when no one else does it that

- 73. way and their own manager or supervisor does not role model expected performance. If the manager has not used an informed approach to make sure the employee is completing the right training to produce measurable results then the manager really doesn’t know what to look for when the employee returns from training. Many managers send staff for training in the hope that the trainer’s magic will rectify the staff member’s performance issues. In your place of work, what are the consequences for employees who do not apply what has been taught in a training session or does anyone even know? There are numerous skills and knowledge components that employees are taught in training that are seldom checked on the job to see if the learning transfer occurred. Where knowledge and skill relates to easily measured tasks that are frequently checked it is easy to see learning transfer gaps.

- 74. When these are identified, what are the consequences or the actions taken? What should or could a manager’s role be in bridging the transfer of learning to improved performance for newly trained staff? Do managers take an active or passive role when learners return from training? Oftentimes employees learn concepts and theory in their training, which they have trouble transferring to the reality of their workplace. They may lack the confidence to apply new techniques or knowledge back at work, or lack the experience and practice with the better, newly learned, processes, sometimes they need to relearn how to juggle multiple new skill and knowledge requirements in an efficient manner in order to function in their work day. The manager’s role in the transfer of learning to the workplace Helen McPhun

- 75. STRATEGY www.aitd.com.au TRAINING & DEVELOPMENT | DEC 13 | 05 | It seems, in some workplaces, employees are ‘sent off to get fixed’ by training. When they return no one checks. Surely managers have a key role in managing the newly trained employee to apply what is learnt and perform. There are workplaces where a trainee returns from training and the manager and colleagues encourage the employee to use the new skills and knowledge. Where workmates are supportive and where senior management actually knows what training is occurring. In this instance learning would certainly be transferred into performance improvement. The key to making learning stick is to

- 76. encourage employees who have been trained to apply what they have learned. They also need to be measured to see that they are applying the knowledge and skills the correct way in the right contexts. It is not just the trainee’s responsibility to transfer learning to work. The manager must promote and encourage an environment that supports the application of the new learning. This may include team members sharing what they have learnt in a team meeting. The colleagues must also be onboard to contribute to a positive learning culture. Each person must be role modelling what the trainee has been taught. Where the learning is not transferred to the workplace there should be consequences. Those consequences should not be sending the same person off to a similar course, but rather include learning application goals and targets to be achieved within reasonable timeframes.

- 77. Where senior managers are approving the training spend of other managers and supervisors, they need to check that there is a return on this training spend. The requirements to provide a bridge from training to learning and then from learning to improved performance is upheld by multiple players. A learning culture is grown from within by everyone and not dictated as the new initiative from HR, OD or senior managers. A learning culture provides a bridge for newly trained employees which encourages them to apply their learning on the job and measures whether the learning has improved their performance. Helen McPhun is a Director and Learning and Evaluation Specialist for McZoom Ltd a consulting practice based in Auckland, New Zealand. Helen is the Education Director for LEARNPLUSTM – a Category One,

- 78. NZQA accredited school offering Management and Adult Education qualifications. Contact via [email protected] or [email protected] C R IC O S 0 0 2 3 3 E_ ju n

- 79. io rG U 3 6 7 9 6 The next step in developing your training expertise Master of Training and Development (MTD) This customised professional studies degree is designed to take your knowledge and skills in learning engagement to the next level. The MTD is for people who want to build upon their professional experience to advance their knowledge of training and development.

- 80. So, if you’re aiming to move into training or teaching, staff development, or to extend your knowledge and skill in adult education, we can offer you an effective education pathway. The MTD is an 80 credit point program* with the option of completing by part dissertation. Our blended approach to delivery includes face-to-face, online and distance engagement with lecturers. For those without an undergraduate degree, the Graduate Certificate in Training and Development is a stand-alone qualification of 40 credit points and a pathway to the MTD. To find out more visit griffith.edu.au/education/adult- vocational-education or contact Mark Tyler [email protected] *Please note that the overall volume of learning for the MTD is set to increase to 160 credit points in 2015.

- 81. Copyright of Training & Development (1839-8561) is the property of Copyright Agency Limited and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use. Studies in Business and Economics - 82 - Studies in Business and Economics THE INFLUENCE OF SUPERVISORY AND PEER SUPPORT ON THE TRANSFER OF TRAINING

- 82. NG KUEH Hua University Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia Abstract: The burgeoning literature investigating the effect of supervisory support on the transfer of training is characterized by inconsistent findings. Also, to date, research examining peer support is still lacking, despite earlier studies show support emanating from co-workers has a significant influence on the transfer of training. Hence, this study attempts to rectify the inadequacies in the literature by examining the effects of supervisory and peer support on the transfer of training. Based on a cross-sectional method, quantitative data was collected from 100 employees working in one of the Malaysian state health departments, with a response rate of 48 percent. The results of multiple regression analysis revealed that supervisory support was not significantly associated with transfer of training, whereas peer support exerted a significant and positive influence on transfer of training. This study responded

- 83. to the pressing calls for more studies to elucidate the relationship between social support and the transfer of training. The findings contributed to the body of literature by clarifying the nature of relationships between supervisory support, peer support and transfer of training, particularly from the Malaysian workplace perspective. Key words: Supervisory support, peer support, transfer of training 1. Introduction Over the years, organizations increasingly invest on training and development to improve employees’ work performance. It is estimated that organizations in the United States spend approximately $130 billion annually on training and development (Paradise, 2007). Unfortunately, only a small portion of

- 84. learning is actually transferred to the job (Pham, Segers & Gijselaers, 2010). As a result, it is not surprising that human resource practitioners often questioning to what extent employees are able to change their behaviour after attending training (Blume, Ford, Baldwin & Huang, 2010). Practitioners have been experimenting with various organizational interventions that are proven by training researchers as effective and reliable in promoting the transfer of knowledge, skills and attitudes (KSA) on the job (Ford & Weissbein, 1997; Cheng & Studies in Business and Economics Studies in Business and Economics - 83 - Ho, 2001). However, this method is often costly, time- consuming and required a lot of