Description Total Possible Score 6.00General ContentSubje.docx

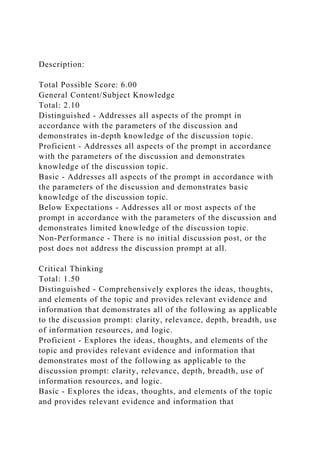

- 1. Description: Total Possible Score: 6.00 General Content/Subject Knowledge Total: 2.10 Distinguished - Addresses all aspects of the prompt in accordance with the parameters of the discussion and demonstrates in-depth knowledge of the discussion topic. Proficient - Addresses all aspects of the prompt in accordance with the parameters of the discussion and demonstrates knowledge of the discussion topic. Basic - Addresses all aspects of the prompt in accordance with the parameters of the discussion and demonstrates basic knowledge of the discussion topic. Below Expectations - Addresses all or most aspects of the prompt in accordance with the parameters of the discussion and demonstrates limited knowledge of the discussion topic. Non-Performance - There is no initial discussion post, or the post does not address the discussion prompt at all. Critical Thinking Total: 1.50 Distinguished - Comprehensively explores the ideas, thoughts, and elements of the topic and provides relevant evidence and information that demonstrates all of the following as applicable to the discussion prompt: clarity, relevance, depth, breadth, use of information resources, and logic. Proficient - Explores the ideas, thoughts, and elements of the topic and provides relevant evidence and information that demonstrates most of the following as applicable to the discussion prompt: clarity, relevance, depth, breadth, use of information resources, and logic. Basic - Explores the ideas, thoughts, and elements of the topic and provides relevant evidence and information that

- 2. demonstrates some of the following as applicable to the discussion prompt: clarity, relevance, depth, breadth, and use of information, and logic. Below Expectations - Attempts to explore the ideas, thoughts, and elements of the topic and provide relevant evidence and information, but demonstrates few of the following as applicable to the discussion prompt: clarity, relevance, depth, breadth, use of information resources, and logic. Non-Performance - There is no attempt to explore the ideas, thoughts, and elements of the topic and provide relevant evidence and information in either the original post or subsequent response posts within the discussion, or no post is present. Written Communication Total: 0.60 Distinguished - Displays clear control of syntax and mechanics. The organization of the work shows appropriate transitions and flow between sentences and paragraphs. Written work contains no errors and is very easy to understand. Proficient - Displays control of syntax and mechanics. The organization of the work shows transitions and/or flow between sentences and paragraphs. Written work contains only a few errors and is mostly easy to understand. Basic - Displays basic control of syntax and mechanics. The work is not organized with appropriate transitions and flow between sentences and paragraphs. Written work contains several errors, making it difficult to fully understand. Below Expectations - Displays limited control of syntax or mechanics. The work does not include any transitions and does not flow easily between sentences and paragraphs. Written work contains major errors. Non-Performance - Fails to display control of syntax or mechanics, within the original post and/or responses. Organization is also not present.

- 3. Engagement/ Participation Total: 1.80 Distinguished - Contributes to classroom conversations with at least the minimum number of replies, all of which were thoughtful, relevant, and contributed meaningfully to the conversation. Fully engages in the conversation with appropriate topic-based responses. Proficient - Contributes to classroom conversations with the minimum number of replies that are somewhat thoughtful, relevant, and contributed meaningfully to the conversation. Attempts to fully engage in the conversation with appropriate topic-based responses. Basic - Contributes to the classroom conversations with the minimum number of replies. Attempts to fully engage in the conversation, but the responses are not relevant or fully aligned with the discussion topic. Below Expectations - Attempts to contribute to the classroom conversations with fewer than the minimum number of replies; however, the replies are not thoughtful and relevant, or they do not contribute meaningfully to the conversation. Non-Performance - There is no contribution to the discussion. Powered by Chapter 5 Principles of Universal Design for Learning AP Photo/Janet Hostetter Learning Objectives After reading this chapter, you should be able to: · Describe the intrinsic barriers associated with efforts to design for the average student and provide an example of how this type of design might look in the classroom. · Summarize the conceptual foundations of universal design for learning.

- 4. · Demonstrate three methods for improving the accessibility of text. · Identify the accessibility barriers found in audio files and video files, and suggest what features must accompany these types of media to make them universally accessible. · Demonstrate how you could implement universal design for learning in your classroom using the principles of multiple means of representation or multiple means of expression. 5.1 The Importance of Accessible Design When designers create a new product, they are seeking to solve a problem through innovative design. Perhaps you have heard the phrase, "Build a better mousetrap, and the world will beat a path to your door" (Kassinger, 2002, p. 128). This statement speaks to the value of innovative design for solving practical problems. However, design and invention are always contextualized within a time period and a specific culture, and are subject to the limitations of contemporary technologies and materials. As a result of recent advances in technology, it is now possible to design tools, products, and information resources in ways that make them accessible to diverse individuals. In this section, readers will be introduced to principles from the field known as accessible design. You will learn how designs that focus on the special needs of individuals with disabilities can improve the user experience for these individuals while also having secondary benefits for everyone. Design for the Mean One common design strategy is known as "design for the mean." As shown in Figure 5.1, using this approach, the designer is focused on creating a product that will reach the largest number of people to ensure that it is commercially successful. Figure 5.1: Design for the mean A product that is designed for the mean seeks to achieve

- 5. commercial success by reaching a large percentage of people in the mainstream. The blue line represents the standard bell curve. The shaded area below the peak indicates the target mass market of the average user. In education, "design for the mean" takes on the form of one textbook that is written, purchased, and distributed to every student at a specific grade level. Similarly, design for the mean is the key instructional principle when a teacher decides that all students will write a three-page book report to demonstrate that they have read and understood a specific book. Another example of design for the mean is the traditional lesson plan book where teachers record their plans for covering content (see Figure 1.7 in Chapter 1). When designers assume that everyone is like them (e.g., average height and weight, able to read at grade level), the product they create will inevitably meet the needs of only a limited range of users. As an example, consider the fiasco with the Amazon Kindle where designers failed to recognize that blind readers would want to use a handheld reading device and that they would need voiced navigational menus—a design decision that was reversed after 6 months of complaints and disability advocacy (Amazon.com, 2009). Without an appreciation for the fundamental ways that people are different, it is unlikely that designers will be able to design products that meet the accessibility and usability needs of all learners because they will not understand the special needs of some. Clearly, there is much more to learn about how to meet the instructional needs of diverse learners, and until we begin describing the salient nature of these differences in ways that inform design (see Table 5.1), it is unlikely that we will design products that meet the needs of all learners. Table 5.1: Diversity and instructional design Student Performance Variable Range of Diversity

- 6. Memory Students develop increased capacity in short- and long-term memory as they grow. Some disabilities interfere with information storage and retrieval and therefore may require explicit strategy instruction. Motivation Students will display varying levels of persistence in completing a task that may be related to their previous success with similar previous tasks. Therefore, choice of challenge and dependency on adults are important aspects to monitor. Over time, learners develop intrinsic motivation for completing challenging tasks. Sustained Attention Span Ranges from 8 seconds for 2-year-olds to 40 minutes for young adults. Attention deficit disorder may affect attention span. Over time, learners develop expanded attention spans that allow them to focus on complex cognitive tasks. Speech and Language Speech and language begins developing in very young children and provides a foundation for accelerated development once children reach school-age. Some disabilities will impair a child's oral communication skills and therefore may require other methods of communication, such as a communication board or augmentative communication system. Fine Motor Skills Fine motor tasks require a level of eye–hand coordination and fluency that is first learned as a preschooler and evolves over time. Some disabilities will impair fine motor skills, and this

- 7. has applications for student work that may involve handwriting, keyboarding, and manipulating objects such as turning pages in a book or using a computer mouse, etc. Reading Children's early learning experiences frequently prepare them for formal reading instruction. Reading skills are measured by grade levels and Lexiles. The goal is to match the difficulty of a text with the student's independent or instructional reading level. It is common to find a range of reading levels at every grade level (some students will be reading at several levels below grade level, and some students will be reading at levels above grade level). Problem Solving As in each of the other areas, children's mathematical and problem-solving skills will vary considerably at each grade level. Young children and students who have difficulty with the conceptual processes of problem solving benefit from the use of manipulatives. Older students learn how to support their problem-solving skills by using tools such as graphing calculators and spreadsheets. At this point, it is important to understand two related concepts: accessibility and usability. Accessibility refers to the inclusive goal of designing tools, products, and information resources to be usable by all people regardless of their skills or abilities. Usability, in turn, refers to how easy it is to learn and use a product. When considering any tool, product, or information resource, it is necessary to evaluate both the accessibility and usability (Lazar, 2007). A key principle of accessible design involves understanding that the special needs of individuals with disabilities can produce solutions that benefit other groups.

- 8. For example, knowing that some people have a vision impairment can translate into a design principle that all text should be adjustable, if necessary, by users so that they can enlarge the text to a size sufficient for comfortable viewing. Although vision impairments are a specific disability, the same text enlargement intervention can benefit most adults who experience decreased visual acuity as they age. The fundamental problem of the design for the mean approach is that the resulting tool, product, or information may be inaccessible for many individuals. That is, because the designer focused on only meeting the needs of a specific segment of the population (Hackos & Redish, 1998; Lidwell, Holden, & Butler, 2010), the product may not be accessible or usable by many others. Again, consider the textbook that is written with the expectation that all students read at grade level. Quite readily we can identify at least three groups of students whose needs will not be met. For example, a student who is blind will not be able to access the printed textbook. A student with a reading disability will not be able to independently read the information. Third, while a gifted student will be able to read the information, she may not be sufficiently challenged to learn at a level commensurate with her ability. As a result, design for the mean involves assumptions about the average student and fails to meet the needs of students whose skills and abilities fall outside that range. The printed textbook had many positive attributes in the early 20th century. Clearly the technical advances that allowed printing costs to be reduced such that each student could study from his or her own textbook was an important advancement in education. However, the historical one-size-fits-all textbook is a poor match for the needs of diverse learners in the 21st century because of the fixed layout, font size, reading level, and language. This situation creates the need for accommodations and modifications to make the textbook accessible to diverse individuals by converting it to a digital format that will permit the student who is blind to access the text through refreshable

- 9. Braille, the student with a reading disability to listen to the text with a text-to-speech tool, and the gifted student to pursue more advanced topics through hyperlinks. A characteristic of innovation is the development of new technologies. Therefore, if we consider the achievement gap to be a result of the limitations of traditional instructional design in education, it is necessary to explore instructional designs that are more inclusive (Burke, Hagan, & Grossen, 1998; Coyne, Kameenui, & Simmons, 2004; Edyburn, 2010). Design for More Types The principles of universal design have emerged from our understanding of the design of physical environments for individuals with disabilities. As a result, the term universal design is most commonly associated with architecture (Preiser & Ostroff, 2011; Steinfeld & Maisel, 2012). These developments have provided important insights regarding the need to prepare architects and designers to understand special needs to ensure that their designs are accessible from the outset, rather than requiring costly building modifications later. Perhaps the best example of the success of universal design principles is curb cuts. Originally designed to improve mobility for people with disabilities within our communities, curb cuts not only accomplished that goal, but they also improved access for people navigating their community with baby strollers, roller blades, bicycles, and so on. Curb cuts addressed the special needs of people in wheelchairs by providing better accessibility. iStockphoto/Thinkstock Another well-known example of accessible design in the built environment is what is known as the zero-entry swimming pool. This type of pool design was created to provide access for individuals in wheelchairs but has proven to be excellent for anyone seeking to enjoy the water without becoming completely submerged. Readers may also encounter the term universal design in the

- 10. context of the home remodeling industry if you are caring for an aging parent. Thus, home remodelers have discovered that specific types of changes to the living space (i.e., kitchen, bathroom, bedroom) make a home more accessible, and safer, for aging adults. Many families explore universal design home remodeling options, such as changing out door knobs, altering countertop heights, and modifying toilets and showers, as a cost-effective alternative to nursing homes. Indeed, many of the universal design interventions for individuals with disabilities are also relevant for facilitating the independence of older adults. Another application of universal design concepts was created in the 1990s as the underlying principles were applied to computers. Gregg Vanderheiden at the TRACE Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, spearheaded conversations among the disability community and technology developers concerning initiatives to include disability accessibility software as part of the operating system. At the time, a person with a disability would need to seek out the services and assistance of an assistive technology specialist in order to be able to independently use a computer. Vanderheiden argued that many accessibility needs could be addressed, not only for individuals with disabilities but also for older adults, by installing the specialized accessibility software on each computer when it was shipped, rather than being added later as an accommodation. After a period of time, the computer manufacturing industry found Vanderheiden's argument persuasive and agreed to install an accessibility folder within the operation system. As a result, since the mid-1990s, every computer that is shipped in the United States has an accessibility control panel that allows users to customize the operation of the computer to accommodate physical, sensory, and, to a limited extent, cognitive disabilities. Thus, accessibility control panels on computers represent a powerful example of universal design that moves the construct from simply focusing on the built

- 11. environment to one that illustrates the importance of making tools and information accessible. The historical lessons learned through these cases have led to a statement that serves as a mantra for universal design: "Good design for people with disabilities can benefit everyone." While universal design is often advocated for as "design for all," in practice this has been difficult to achieve. A more practical way to think about universal design is "design for more types" (see Figure 5.2). This means that we seek to understand the accessibility and usability barriers that individuals encounter and create new tools, products, and information resources that are inclusive to more individuals than would be the case with ordinary design for the mean approaches (see Figure 5.1). We will explore the practical implications of this concept further in Section 5.3. Figure 5.2: Design for more types Design for more types reflects the goal of universal design by expanding the zone of accessibility and usability beyond a small segment of the population (as contrasted with Figure 5.1) in order to include as many individuals as possible. Recognizing and Responding to Differences As discussed in Chapter 3, over a lifetime, each of us, or someone we know, will encounter limitations due to aging, disease, accident, and/or disability that may impair basic life functions such as hearing, seeing, self-care, mobility, working, and learning. While some of us may be born with a disability or disease that will require us to overcome limitations throughout our lives, others will need to learn how to respond to challenges that arise from an accident or simply as a result of growing older. In other words, we must learn to recognize that differences and limitations are fundamentally part of the human condition. In the classroom, it is important to think about learner differences as part of the instructional planning process. For example, shouldn't we expect to find great variation in students'

- 12. knowledge and skills? When we walk into any classroom, we should anticipate differences among students relative to the following: attention span persistence reading ability handwriting legibility number sense and problem-solving skills oral communication skills. Diverse students encounter a variety of barriers in school, both obvious and hidden, as demonstrated here. Obvious Barriers Stairs for a person in a wheelchair or a person on crutches Print for a person who is blind Audio for a person who is deaf Video for a person who is blind Hidden Barriers Attitudes One-size-fits-all approaches Text that is fixed Poor design Time limits Often learner differences are viewed as a negative, outside of a range that we think we can manage (e.g., "Oh, I can't teach that student; he's blind."). When we fail to recognize the range of diversity found in the population, there will be a need for an accommodation (i.e., "We'll see if we can get a copy of the textbook in Braille."). Contrary to this narrow and often negative approach to diversity, the goal of universal design is to proactively value differences—that is, to anticipate learners' differences before they enter the classroom so that we can support their academic performance before they fail. This is consistent with McLeskey and Waldron's (2007) description of the goal of special education as "making differences ordinary." As a result, we need not only to recognize diverse learners in our classrooms

- 13. but also to respond to their needs before they fail. Universal design for learning is a specialized application of universal design and is an approach that holds considerable promise for meeting the needs of diverse learners. 5.2 Foundations of Universal Design for Learning The origin of the term universal design for learning is generally attributed to David Rose, Anne Meyer, and their colleagues at the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) (Edyburn & Gardner, 2009). However, a fact that is often overlooked is that the principles of UDL were developed during the period before and after the 1997 reauthorization of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). During that time, both general and special educators were preoccupied with issues associated with implementing inclusion. While students with disabilities had gained physical access to the general education classroom through inclusion, concerns were being raised about how students would gain "access to the general curriculum." An interpretive document about universal design for learning (Orkwis & McLane, 1998) was disseminated extensively and served to generate the first wave of national attention to the construct. McLaughlin (1999) reported that IDEA reauthorization contained several specific mandates relative to making the general curriculum accessible for students with disabilities: Statements of a child's present level of educational performance to specify how his or her disability affects involvement and progress in the general curriculum. IEP teams to design measurable annual goals, including short- term objectives or new benchmarks, to enable the child to be involved—and progress—in the general curriculum. A statement of the special education and related services and supplementary aids and services to be provided to the child. A description of any program modifications or supports for school personnel necessary for the child to advance appropriately toward the annual goals, to progress in the general curriculum, and to be educated and participate with other

- 14. children both with and without disabilities. IEP team members to document an explanation of the extent, if any, to which the child will not participate with children without disabilities in the general class and activities. Readers interested in a legal analysis of the issues associated with access to the curriculum are encouraged to review Karger and Hitchcock (2004). These issues were at the forefront of CAST's work, and in 1999 CAST received a federal grant to establish the National Center on Accessing the General Curriculum, which became instrumental in garnering national attention for the potential of UDL. As CAST's insights about UDL were taking shape, staff members presented their work at the annual Office of Special Education Project (OSEP) Director's conference in 2000. CAST also used publication outlets to describe its ideas about how universal design could be applied within education (Meyer & Rose, 2000; Rose & Meyer, 2000). The second wave of widespread attention to UDL came in 2002 when Rose and Meyer published a book called Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age, which has become the definitive work about UDL (also available online, http://www.cast.org/teachingeverystudent/ideas/tes/). The authors elaborated on the conceptual framework of UDL, pointing out that it is grounded in emerging insights about brain development, learning, and digital media. Rose and Meyer also called attention to the disconnect between an increasingly diverse student population and a one-size-fits-all curriculum, arguing that these conditions would not produce the desired academic achievement gains expected of 21st-century global citizens. Challenging educators to think of the curriculum as disabled, rather than students, their translation of the principles of universal design from architecture to education are nothing short of a major paradigm shift (Edyburn & Gardner, 2009). CAST advanced the concept of universal design for learning as a means of focusing research, development, and educational practice on understanding diversity and applying technology to

- 15. facilitate learning. CAST's philosophy of UDL is embodied in a series of principles that serve as the core components of UDL: Multiple means of representation to give learners various ways of acquiring information and knowledge; Multiple means of expression to provide learners alternatives for demonstrating what they know; and Multiple means of engagement to tap into learners' interests, challenge them appropriately, and motivate them to learn. Multiple means of representation may be understood as providing students with alternatives to learning information beyond solely using a textbook. Teachers today have many choices when it comes to presenting instructional content to students: Watch a YouTube video, listen to a podcast, read text on a webpage, look up a topic using Wikipedia, and more. The key notion is to break out of the one-size-fits-all model, which assumes that all students learn in the same way, and to encourage teachers to use a wider palette of information containers to reach diverse students. A teacher takes his class on a field trip to learn about ecosystems. What are some other ways teachers can present information to students without using a textbook, while capturing different learning styles? iStockphoto/Thinkstock Multiple means of expression draws attention to the need to provide students with multiple methods of demonstrating what they know. Some teachers recognize the value of this principle as they allow students a choice of writing a paper, preparing a slideshow presentation, recording a video, and so on. The key notion is to provide students with choices in how they demonstrate what they have learned and the media they use to express themselves. Twenty-first century educators will likely need to alter their instructional practices in order to place students in the role of Goldilocks: that is, allowing them to try multiple options to determine which option is "just right" for ensuring that their performance meets increasingly high

- 16. standards. Principles of fairness dictate that equity is achieved when every student receives what he or she needs (Welch, 2000). Of the three principles above, perhaps the most important is multiple means of engagement, which is based on the learning principle that deep learning is only accomplished through sustained engagement. Access to the curriculum is a prerequisite to engagement. However, sustained engagement is achieved by activities that are interesting, motivating, and at the right challenge level, what Vygotsky (1962) calls the Zone of Proximal Development. Indeed, research has demonstrated the relationship between deep learning and high levels of performance and expertise (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Schlechty, 2002). CAST has elaborated on these core principles through the development of UDL Guidelines (CAST, 2011). As illustrated in Figure 5.3, each of the three core principles has been expanded to include three guidelines that speak to the instructional design features that are needed to implement each principle. Teachers and instructional designers can use these guidelines as they create instructional materials. Figure 5.3: CAST's UDL principles By following the core guidelines for providing multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement, teachers can help shape more informed, goal-oriented, and determined learners. Source: CAST (2011). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.0. Wakefield, MA: Author. http://www.cast.org. Policy Foundation The impact of universal design for learning can be traced through U.S. federal special education law. Thus, in the 2004 reauthorization of the Individual With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which governs special education, the term universal design was officially defined (20 U.S.C. § 1401): The term universal design has the meaning given the term in

- 17. section 3 of the Assistive Technology Act of 1998. (U.S.C. § 3002) Following the backward chain of legal reference, the definition of universal design as it was included in the Assistive Technology Act of 1998 is as follows: The term "universal design" means a concept or philosophy for designing and delivering products and services that are usable by people with the widest possible range of functional capabilities, which include products and services that are directly usable (without requiring assistive technologies) and products and services that are made usable with assistive technologies. (U.S.C. § 3002) Next, consider how the terms are defined in the Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-315, Section 103, a): (23) UNIVERSAL DESIGN. – The term 'universal design' as the meaning given the term in section 3 of the Assistive Technology Act of 1998 (29 U.S.C. 3002). (24) UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING. – The term 'universal design for learning' means a scientifically valid framework for guiding educational practice that – (A) provides flexibility in the ways information is presented, in the ways students respond or demonstrate knowledge and skills, and in the ways students are engaged; and (B) reduces barriers in instruction, provides appropriate accommodations, supports, and challenges, and maintains high achievement expectations for all students, including students with disabilities and students who are limited English proficient. As illustrated, the definition of universal design for learning evolved from a concept or philosophy in 1998 to a scientifically validated framework in 2008. Of concern is the fact that to date, although there is a significant body of work on universally designed assessment (e.g., Ketterlin-Geller, 2005; Thompson, Johnstone, & Thurlow, 2002), there has been little research on UDL. Thus, without an adequate base of primary research, an

- 18. analysis of research evidence that establishes UDL as a scientifically validated intervention is not yet possible (Edyburn, 2010). Evidently, the work CAST compiled to support various components of UDL design principles (CAST, 2011) was mischaracterized by lobbyists and written into federal law. Unfortunately, the claim that UDL has been scientifically validated through research cannot be substantiated at this time. Over the past 10 years, universal design for learning has captured the imagination of policymakers, researchers, administrators, and teachers. Universal design for learning provides a vision for breaking the one-size-fits-all mold and therefore expands the opportunities for learning for all students with learning differences. Recognizing and responding to diversity is a core motivation for engaging in UDL practices. Finally, the expectations associated with No Child Left Behind (NCLB) makes UDL an important and timely strategy for enhancing student academic achievement. The mantra that evolved from our understanding of the value of curb cuts, "Good design for people with disabilities benefits everyone," provides a powerful rationale for exploring large-scale application of UDL in education. One of the significant flaws in a federal law that states that UDL is a scientifically validated framework is that CAST's UDL framework does not feature a component associated with the measurement of student learning outcomes. All three of the "multiple means" statements by CAST focus on the provision of multiple concurrent interventions. As a result, within existing conceptualizations of UDL, there is no clear way to measure claims that UDL is effective for enhancing the academic performance of diverse students. This is a significant shortcoming for anyone trying to operationalize, implement, and evaluate a UDL program. The Potential of Universal Design for Learning Anne Callies, Assistive Technology Lead for the San Diego Unified School District, speaks about how new technology

- 19. promotes accessability. How does this technology support UDL frameworks? Translating UDL Theory Into Practice Without seeing a class list, in a class of 30 middle school students, one can anticipate that 5–7 students have below grade- level reading skills, 3–5 students will have learning disabilities, 1–2 may have vision or hearing difficulties, and 1–2 students may have a primary language other than English. The current model of curriculum accommodations requires that these students first be identified as having special needs, and then special support services will be provided. The promise of universal design for learning suggests that instructional materials can be designed to provide adjustable instructional design controls. One way to think about these controls is to consider a volume control slider that is adjustable to be off or some level between low and high. Tomlinson (1999) speaks of this concept as equalizers. As illustrated in Figure 5.4, universal design control panels could be included in all instructional software and be accessed by students and teachers when an adjustment is needed. Just think of it: Do you need reading materials at a lower readability? Just go into the control panel and reset the slider, and the same information could be presented at a lower reading level. Figure 5.4: Model of equalizers Table 5.2: Instructional designs that proactively value differences Instructional Challenge Strategy Technology Options Design instructional materials that support diverse learners before they fail. Create multilingual instructional materials that include a variety of levels to engage students at different skill levels. Literacy Center Education Network

- 20. http://www.literacycenter.net/lessonview_en.php Create instructional text at multiple levels to account for different reading levels and interest levels. Ben's Guide to U.S. Government for Kids http://bensguide.gpo.gov/ Create tiered instructional text and offer audio support for the easier levels. StarChild http://starchild.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/StarChild/StarChild.html Create tiered instructional materials for adults to understand the importance of just-in-time support. The Brain: From Top to Bottom http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/ The figure shows a model of equalizers that could be used to adjust the difficulty of curriculum and/or the type of supports that are activated to support diverse learners. Many find it difficult to visualize what universally designed curricula might look like. Table 5.2 identifies digital resources that can help us understand the potential of UDL. As you explore each resource, consider how it was designed to support the success of all learners by embedding supports that can be used by any learner as needed. Also consider the question: Would these instructional materials be helpful to a single student (if so, it might be considered assistive technology), a small group of students (if so, it might be useful as a Response to Intervention [RTI] Tier 2 intervention), or might there be value in giving them to the entire class in order to reach those who we know will struggle as well as many other students whom we cannot identify in advance? Finally, consider the

- 21. difference between traditional textbooks (design for the mean; see Figure 5.1) and these types of digital learning materials that feature embedded supports that can be used by any learner (design for more types; see Figure 5.2). 5.3 Universal Access to Text The text found in textbooks is fixed. That is, the font is a certain size. The leading (the space between lines) is fixed. The margins are fixed. The font color is usually black (to provide a striking contrast against the white paper). While the characteristics of print and books have changed little since the invention of the printing press, we now know that to some people the book is a difficult container in which to access information. For example, consider the child who was born without arms. How does he turn the pages of the book or carry the book from his desk to his locker? What about the child who has a vision impairment and needs the text enlarged to be able to see the print? What about a child whose first language is not English, of what use is the textbook to her? And what about the student who cannot read independently at grade level? By converting printed text into digital format, you can make text more accessible to students. What are other advantages to students accessing text digitally? iStockphoto/Thinkstock Typically, the first step in making the information accessible is to scan the text into the computer (see Chapter 6) to create a digital version of the text. Digital text is inherently flexible. That is, the size, font, and color of the text can be readily altered. In addition, digital text can be manipulated in ways that provide physical, sensory, and cognitive access. To meet the needs of diverse learners, it is becoming increasingly clear that 21st-century curricula should be developed, stored, and used in a digital format, and print-on-demand tools should be used as needed. Notice how the traditional paradigm has been flipped. Rather than creating print books that have to be converted into digital format, books should be created and distributed in

- 22. electronic formats and printed when the need arises. This section outlines a series of design interventions that make text universally accessible. The goal is to present resources, strategies, and tools that you can use in your classroom to ensure that your students will have universal access to text- based information. Text Creation Today, almost all information is created through the use of a keyboard and a computer. This means that most text is "born" digital. As you learned while mastering your word processor, it is easy to save, change, and print documents when the text is saved in a word processor. As a result, few people who have mastered the basic mechanics of a word processor want to go back to using a typewriter or writing entirely by hand. One of the simplest strategies that teachers can use to make text accessible to their students is to provide digital copies (i.e., created on a word processor) of their handouts. In fact, many school districts support this strategy by providing teachers with an online workspace on a local area network (i.e., intranet) or a content management system (e.g., Moodle). These types of tools allow teachers to post documents online. In both cases, students learn to retrieve documents from the server that they can open and view in their own word processor or web browser. Alter the View Students who need to alter the view of a document can use the zoom feature in their word processor (Click on View menu, Click on Zoom, select appropriate size) or web browser (Command + or Command -) to increase the font size. This is another excellent example of universal design. That is, while zoom was originally developed for people with visual disabilities, nearly everyone periodically discovers the need to enlarge text in order to see information more comfortably. A key design principle for making text accessible on webpages uses a web development technique known as Cascading Style Sheets (CSS). CSS is a preferred web development practice because it separates content from the display of information.

- 23. This is really a significant development for accessibility because in the past all decisions about the appearance of text were made by the designer or publisher. By separating content from the characteristics of how information is displayed, the control has shifted from the publisher to the reader, who determines what is the "just right" format. Visit the following website to experience CSS: CSS Zen Garden http://www.csszengarden.com What you will notice is that as you click on each link on the CSS Zen Garden site, the content of the pages stays exactly the same, but the graphic design, layout, text style, and so on, change. The magic of CSS is accomplished by saving the text in one file and saving the CSS variables that affect the appearance of the page in a second file. The point of this website is simply to illustrate that accessible design can be beautiful. When you see webpages that have a series of boxes with the letter A or T, this is an indication that the webpage has used CSS to build in text enlargement. Simply click on the letter to enlarge the text to a comfortable size. The value of text enlargement has led to a number of new tools, some of which are designed to work within your web browser (i.e., browser plugin or bookmarklet). Increasingly common is the need for these same kinds of tools to work on smartphones given the very small screen size and the need to remove the clutter found on many webpages (see Table 5.3). Hence we are seeing another example of universal design that is transforming what was originally an assistive technology intervention into a universal design feature that benefits everyone. Table 5.3: Bookmarklets and apps that alter readability features of text Instructional Challenge Strategy Technology Options

- 24. Need to modify the screen presentation of text to improve its readability. Download a bookmarklet to be used when reading in a web browser. Readability http://www.readability.com/bookmarklets Evernote Clearly http://evernote.com/clearly/ Download an app to improve the readability of webpages on a smartphone screen. Readability http://www.readability.com/apps Another important strategy for making text accessible involves styles. Perhaps you used style sheets when you learned to word process; unfortunately, most of us did not (to learn more, visit http://webaim.org/techniques/word/). The purpose of using a style sheet is that headings and text elements are consistently tagged regarding their function (i.e., Heading 1, body text). While visual users can see the difference in subheadings, blind users cannot. As a result, screen readers rely on style sheets to read the tagged elements of a document and provide the user with the opportunity to move around a document (i.e., using heading tags to jump from one section to another). Styles also offer authors the opportunity to view the headings that they have created in a document in an outline view to ensure that they are being consistent in their writing style.

- 25. Saving the Text File After you have created your text, you have many choices concerning the file format in which you save your document. Table 5.4 summarizes some of the common text file formats. Today, most word processing programs and web browsers can easily open and view documents created in any of these common file formats. In most environments, Microsoft Word® files saved as .doc or .docx are universally accessible because Word® has become the word processing standard. Be considerate of the needs of your students when selecting a file format in which to save the information. For example, if you create a document in WordPerfect® or Pages®, these specialized formats cannot be opened on most computers that do not have these programs installed. In this situation, the student may need to use an online conversion service (see Table 5.5) to convert the file to a format he can open and view. Table 5.4: Common file formats for text File format Attributes .asc ASCII, a generic text file with no formatting properties. A universal standard for the lowest level of text-based information. .doc, .docx Proprietary formats associated with Microsoft Word. Requires Microsoft Word or a compatible word processor to open. .html A file format containing information formatted for the Web. HTM and HTML files will open in a web browser.

- 26. .pdf A proprietary format created by Adobe to facilitate the transfer of documents between computers to ensure compatibility when one user may not own the software that was used to create the original document. Generally recognized as a universal storage format. .rtf Allows some basic formatting (i.e., bold, italics) to be included in the text. The rich text format file type opens in all word processors. .txt A file containing text with no formatting. This text file type opens in all word processors. Table 5.5: File conversion tools Instructional Challenge Strategy Technology Options Unable to open and view a digital file because it is saved in a format that is not compatible with the software on one's computer. Access an online conversion service to upload the file and convert it into another format. Zamzar http://www.zamzar.com

- 27. You Convert It http://www.youconvertit.com Media Converter http://www.mediaconverter.org Manipulating Digital Text Once students have access to a digital text file, they are able to manipulate the information in a variety of ways to make it more accessible. Essentially, the only technology skills needed to do so involve copying and pasting. One important strategy for many struggling readers involves altering the cognitive accessibility of the text. This can be accomplished by copying and pasting digital text into a summarization tool. Search your favorite app store to find summarization products that will work on your smartphone. One example of a free web-based summarization tool is: Text Compactor http://www.textcompactor.com With this tool, students use a slider to determine how much of a summary they want to read, and the summarized text appears in a box on the page. This tool is an interesting application of UDL. Teachers might use it in a class because of a few struggling readers. However, to reach those targeted students, the teacher introduces the tool to the entire class. The potential of UDL indicates that the tool will help not only the small group of targeted students but also a larger number of students in the class—many of whom the teacher could not know in advance would need, want, or benefit from such a tool. This case illustrates that the outcomes of UDL should be considered in terms of primary and secondary beneficiaries. If only a small number of targeted users end up using the tool, it

- 28. functions more like assistive technology. However, if the secondary beneficiaries are a larger group, it is likely we have discovered a UDL application in the same way that we notice the beneficiaries of the zero-entry swimming pool. Once students have a summary of the text, they can choose to copy and paste it into a text-to-speech program. This allows them to listen to information that they may not be able to (or choose not to) read (see Table 5.6). Table 5.6: Text-to-speech tools Instructional Challenge Strategy Technology Options Student would like to listen to text that she cannot or does not want to read. Copy text and paste into a text-to-speech tool. Vozme http://www.vozme.com SpokenText http://www.spokentext.net Read the Words http://www.readthewords.com Finally, digital text affords the opportunity to convert text from English into another language. Some students whose first language is not English will struggle to extract meaning from text found in grade-level readings. Such students may benefit from translation tools that offer the text and audio formats in English and more than 55 languages.

- 29. Google Translate http://translate.google.com The purpose of this section has been to show how something as simple as making digital text available to students in turn allows students to manipulate information to enhance the physical, sensory, and cognitive accessibility of the information in ways that benefit all students. Given the importance of learning from text in American schools, the design of accessible text is a primary starting point for efforts to implement UDL. 5.4 Universal Access to Media The accessibility of instructional media is another important consideration in UDL. While media often supplements text and adds meaning for struggling readers and students who are visual learners, audio and video represent intrinsic barriers for students who have hearing or visual impairments. Thus, efforts to improve accessibility for one population may increase barriers for others. This means we must constantly be attentive to assumptions about our learners and the barriers associated with specific types of information containers we select to use in instruction. However, because of the routine use of audio and video for learning, there are clear guidelines for how to make multimedia content accessible. Accessible Design of Audio Audio files may contain music; a recorded conversation like a radio show, podcast, or interview; spoken text that has been digitized from a human reader (digitized speech), or synthesized speech (generated by a computer voice). While this content may enhance the learning experience for many learners, the audio format poses intrinsic barriers for individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing. Therefore, the key design principle when including audio in instructional materials is to provide a transcript whenever an audio file is made available to students. Transcripts are simply text files that feature the same information that is found in the audio file. For example, if the audio is a radio interview, the transcript would be formatted in script format so that the deaf reader can see who says what.

- 30. Descriptions of sounds are also included in a transcript. For example, if the radio interview begins with soft jazz music, this is indicated in the script. Similarly, if there is background noise such as a fire truck siren, this is also noted. Transcripts may be saved in any convenient text format, such as .doc, .docx, .html, or .pdf. The goal is to provide equal access to the information for all learners. The most significant challenge for most educators is generating a transcript when all they have is an audio recording. The most tedious way to produce a transcript is to replay the audio and type up a transcript. However, a more effective approach is to pay a professional to transcribe the audio. A Google search for "transcription services" will help you identify local, regional, and state transcription services and many organizations may have a negotiated contract to provide this service as needed. Increasingly, efforts are being devoted to automating the transcription process (more about this later in the section). Accessible Design of Images Adding images to text facilitates comprehension for most learners. However, for students who are blind, the information contained in an image is obviously inaccessible. In order for a blind person to have access to the visual information, instructional designers must prepare a text description that explains the information found in the graphic. Whereas captions are commonly used to provide a brief description of an image, a person who is blind will need an extended description. The nature of the description depends on the purpose of the image (e.g., a simple graphic to make the design visually interesting versus a graph with data). Extended descriptions may be included in a word processing document or a webpage so that all may access the information, or it may be stored in a separate file to be accessed as needed. When inserting a graphic on a webpage, most web authoring programs prompt the user to add information in what is known as an alt text tag to an image file. The alt-tag directs screen readers and browsers that have turned off graphics to retrieve

- 31. descriptions or text files that provide a text version of the information that is presented in visual format. The alt-tag signals the availability of a text description that can be read to the individual so that he or she can gain access to the visual information that is available to his or her sighted peers. (If you would like to see an alt-tag in action, and you are reading this textbook online, hover your mouse over any image or figure in the book. The text that was written for the alt-tag will automatically appear. As you view the image and read or listen to the description, decide whether or not the description is adequate for understanding the visual information if you could not see the image.) The universal design of images requires that designers include text descriptions of each image. This is not a difficult process, but it can be time-consuming to thoughtfully describe the information found in an image in ways that are useful to someone who cannot see the image and needs additional information concerning factors that sighted individuals may take for granted (i.e., issues of graphic style or context of a photo). To learn more about creating alt text, visit: http://webaim.org/techniques/images/alt_text Accessible Design of Video The popularity of YouTube and Netflix has placed video in the middle of social media and, therefore, it is increasingly finding its way into the classroom for instructional purposes. However, the multimedia nature of video makes it problematic for individuals with sensory impairments (i.e., those who are deaf, hard of hearing, blind, or visually impaired). As a result, educators must ensure that all videos are appropriately captioned. Captioning in the context of video and multimedia means that the information that is presented via audio is available through captions or a transcript and that the information that is presented via video is available through text descriptions (see Table 5.7). Creating captions is a bit more involved than creating a transcript because the text has to be linked to specific audio and video frames. As a result, this is one area of

- 32. accessible design that is difficult to expect teachers to be able to do on a daily basis. However, new tools are making the process easier, and commercial services provide a method for schools to contract for accessibility services if they are creating videos. Table 5.7: Captioning tools for creating accessible media Instructional Challenge Strategy Technology Options An instructional designer is interested in creating universally accessible media for new instructional materials. Add captions and text descriptions to audio and video. Web Captioning Overview http://webaim.org/techniques/captions/ Making Video Accessible http://www.longtailvideo.com/support/jw-player/22/making- video-accessible CaptionTube http://captiontube.appspot.com/ 5.5 Developing a Personal Plan to Implement UDL In the final section of this chapter we will focus on how teachers can plan for implementing UDL in their classrooms. The goal is to provide you with some practical strategies to enhance the accessibility of instruction moving from design for the mean (Figure 5.1) to design for more types (Figure 5.2). We will also address issues that are likely to impact universal design in the near future.

- 33. The A3 Model The transition from inaccessible design to universally accessible design will involve awareness training, new technical development, and time for these new standards to be widely adopted. As a result, achieving universal accessibility will not happen quickly. The A3 Model (Schwanke, Smith, & Edyburn, 2001) illustrates the ebb and flow of concurrent interactions between advocacy, accommodation, and accessibility across a three-phase developmental cycle necessary to achieve universal accessibility (see Figure 5.5). Figure 5.5: The A3 Model The figure shows how advocacy, accommodation, and accessibility shift across the developmental cycle. Source: Adapted from Schwanke, Smith, & Edyburn, 2001. Advocacy efforts raise awareness of inequity and highlight the need for system change to respond to the needs of individuals with disabilities. It is during this phase that advocates seek to spread the message about the benefit of UDL. Part of the message is intended to change the thinking of individuals and organizations about the need for equitable access to tools, products, and information resources. Accommodations are the typical response to advocacy: Inaccessible environments and materials are modified and made available. Typically, accommodations are provided upon request. While this represents a significant improvement over situations in the earlier phase, accommodations tend to maintain inequality because (a) there may be a delay (i.e., time needed to convert a handout from print to Braille), (b) it may require special efforts to obtain (i.e., call ahead to schedule), or (c) it may require going to a special location (i.e., the only computer in the school with text enlargement software is located in the library). Accessibility describes an environment where access is equitably provided to everyone at the same time. Often this is

- 34. accomplished through outstanding design (i.e., ergonomic furniture, software with accessibility and performance supports built in). Thus, this third phase illustrates the goal of universal design in that the majority of instructional materials are universally designed, therefore drastically limiting the number of accommodations needed. It is important to understand that all three factors are present in each phase. However, the waves across each phase suggest the differential impact of the three factors in terms of time, effort, and focus. As a result, individuals and organizations can use the model to assess how their time and effort is being allocated to determine which phase they are currently operating within. CAST's work on UDL paints a vision of the world in which instructional environments, materials, and strategies are universally designed (as found in the third phase). It has created an outstanding series of products (i.e., WiggleWorks [CAST, 1994], Thinking Reader [CAST, 2004], UDL Editions by CAST [2008], CAST UDL Book Builder [2009a], CAST Science Writer [2009b]) that provide experiential evidence of what UDL principles could look like in practice. These products illustrate what might be possible if students had access to a large supply of UDL materials to support their learning across subjects, each and every day of the school year. In the first 10 years of UDL implementation, we have shared the message of UDL with substantial numbers of educators (Phase 1). However, the reality is that once we understand the principles of UDL, we move from Phase 1 (advocacy) to Phase 2 (accommodation). This means that while we are waiting for the widespread availability of the promise of UDL (Phase 3— accessibility), we are left to our own devices to try and apply the UDL principles to create more accessible accommodations (e.g., "Since the webpage does not feature audio, let me show you how to copy the text and paste it into a text-to-speech tool."). Thus, the A3 Model illustrates why many early disciples of UDL find themselves struggling to achieve the potential of UDL within the current limitations of instructional design and

- 35. product development. Pause to Reflect Given your understanding of the A3 Model, which phase do you believe most accurately describes your personal knowledge and skills concerning UDL? A fundamental question that has yet to be fully addressed in the UDL literature is whether or not the demands of daily instruction will allow teachers to function effectively as instructional designers. That is, is UDL a task for developers who make instructional products? Or are teachers the principal stakeholders as they select and deliver instruction in accordance with UDL principles? Given the difficulties the author has observed in trying to scale UDL implementation beyond single classrooms, he is of the opinion that UDL is an intervention that involves the design and creation of instructional materials (Phase 3—accessibility). Hence, the work of teachers is more accurately represented by the description of Phase 2—that is, advocating for universal design for learning, selecting and using UDL materials when they are available, and facilitating accommodations (as illustrated in Section 5.3 for making text accessible). However, this perspective is controversial. In the sections that follow, we explore tools and strategies for implementing universal design in the classroom with the goal of helping teachers design for more types (Figure 5.2). Planning for Multiple Means of Representation The UDL principle of multiple means of representation seeks to provide diverse students with alternatives to gaining information solely from a textbook. You can implement this principle in your classroom by using a planning template. A sample plan, illustrated in Figure 5.6, provides an example of what such a multiple means of representation menu might look like for a middle school lesson on volcanoes. While this planning template does require extra time on the teacher's part, it provides multiple pathways for all students to explore the content, as the teacher may select resources that provide a more

- 36. basic presentation of the information as well as those that provide more advanced content. Because students will review each of the resources, just as Goldilocks does to determine what is "just right," they are likely to accumulate more time on task than commonly found with traditional one-size-fits-all curricula. When teachers seek to implement the UDL principle of multiple means of representation, they are valuing academic diversity by discarding the historical notion that any one information source is the only one needed. In reality, providing students with a menu of information sources is thought to enhance access, engagement, and learning outcomes for both targeted students (primary beneficiaries) who we know will struggle with the content, but also for a large number of other students (secondary beneficiaries) who we cannot identify in advance. Figure 5.6: Sample volcano lessons using the multiple means of representation planning template This figure shows an example of how lessons can be planned using the multiple means of representation planning template. Click here to download the Multiple Means of Representation Template. Planning for Multiple Means of Expression A second principle of universal design for learning focuses on providing students with choices on how they express what they have learned. In many classrooms, teachers expect students to make presentations to the class regarding a topic that they have studied. Beyond formal presentations, teachers are increasingly allowing students to use other formats, such as short videos (http://www.xtranormal.com/), comic strips (http://www.toondoo.com/), and other modes of storytelling and presentation. In this case, the teacher would like each student to make a formal presentation, using one of the tools in Table 5.8. By giving students a choice in the presentation tool, students can opt to learn a new tool, or use one that they are familiar with or

- 37. one that supports specific features (e.g., collaboration [Google Drive]; visualization [Prezi]; or cognitively simplified interface [Kid Pix 3D]) that they want to utilize in this particular context. Because the teacher may not be an expert in each of the products, she directs students to use each other as resources for learning about the tools as well as to take advantage of online help and tutorials. This tactic frees the teacher to devote more time and energy on helping the students learn about the content and performance standards. Once such a menu has been created, it may be reused frequently. Table 5.8: Multiple means of expression menu Instructional Challenge Strategy Technology Options Develop an electronic presentation for the class to report on information that has been learned about a topic. Use electronic presentation software/apps. Google Presentation http://drive.google.com/ Keynote (Macintosh, iPad) http://www.apple.com/iwork/keynote/ Open Office http://www.openoffice.org/ Roger Wagner's HyperStudio 5 http://www.mackiev.com/hyperstudio/index.html

- 38. Kid Pix 3D http://www.mackiev.com/kidpix/index.html PowerPoint http://office.microsoft.com/ Glogster http://www.glogster.com/ Prezi http://prezi.com/ Zoho Show http://show.zoho.com/ Planning for Multiple Means of Engagement Access to information is not the same as access to learning (Boone & Higgins, 2005; Rose, Hasselbring, Stahl, & Zabala, 2005). Access is necessary but not sufficient. As a result, it is important to consider how technology and digital media engage students in meaningful learning activities. When UDL provides the opportunity for a student to access and engage in learning, as minutes of engaged learning accumulate (i.e., time on task), this fosters the opportunity for deep learning to occur. Deep learning, sustained over time, has been found to lead to significant gains in academic achievement. As we seek to

- 39. reverse the effects of the achievement gap, we must keep this strategy in mind. That is, how do we engage students in meaningful learning activities such that they are able to experience the deep learning that is needed for the development of expertise? One strategy for implementing the UDL principle of multiple means of engagement is to use an instructional planning template known as Tic-Tac-Toe. As illustrated in Figure 5.7, a teacher created a Tic-Tac-Toe activity for students in her ninth- grade biology class to complete. In populating the nine cells, she has kept in mind the UDL principles, as she has provided multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement. Students are expected to select three in a row (using the traditional rules of tic-tac-toe) to complete the assignment. Naturally, the creation of tic-tac-toe activities will require a bit of time investment for teachers. However, as an instructional management tool, it is an excellent beginning step for applying the principles of universal design to the classroom. Teachers will reap the dividends of their time investment when they track the academic performance of students who have typically struggled to complete traditional assignments. Often students will ask to do more tic-tac-toe projects. This is a powerful indicator of the instructional value of this intervention and one that operationalizes our values of proactively valuing diversity to support students before they fail. Figure 5.7: Sample tic-tac-toe activity The sample activity shown is based on cells, and is an excellent means of managing universal design principles in the classroom. Source: Permission to reprint granted by Meridith Berghauer.