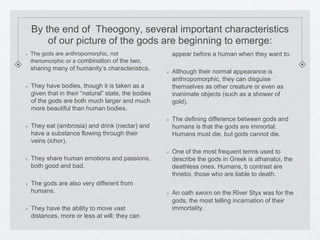

Zeus consolidates his power after overthrowing the Titans by allocating spheres of influence to his brothers - Hades rules the underworld, Poseidon rules the sea, and Zeus rules the sky, though he maintains control over the earth as well. Zeus establishes order through his roles in justice, prophecy, and guest-host relationships. He sires many children both with goddesses and mortal women, though has difficulties producing acceptable sons with his wife Hera, who hates Zeus's mortal offspring. Hesiod's Theogony describes the origins of the Greek pantheon and establishes Zeus as the supreme ruler among the anthropomorphic yet immortal gods.