This document summarizes a study that models changes in surface runoff from drought-induced soil hydrophobicity in watersheds in Ventura County, California. The study uses the Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS) to model 11 watersheds under current conditions and potential future drought conditions. Drought is assumed to increase soil impermeability by 25%, based on previous studies. The model simulates runoff for 2, 10, 25 and 100-year storm events to compare changes in overland runoff under normal and drought conditions. Preliminary results suggest drought could significantly increase surface runoff and flooding risks by reducing soil infiltration capacity.

![Works Cited

"Camarillo Springs Homes Damaged by Mud, Debris Flow." ABC7 Los Angeles. N.p.,

12 Dec. 2014. Web. 05 Nov. 2015.

Clark, James S., et al. "Drought cycles and landscape responses to past aridity on

prairies of the northern Great Plains, USA." Ecology 83.3 (2002): 595601.

Brock, John H., and Leonard F. DeBano. "Wettability of an Arizona chaparral soil

influenced by prescribed burning." JS Krammes [TECH. COORD.]. Proceedings

of a Symposium on the Effects of Fire Management of Southwestern Natural

Resources. 1988.

Doerr, S. H., R. A. Shakesby, and RPD Walsh. "Soil water repellency: its causes,

characteristics and hydrogeomorphological significance." EarthScience

Reviews 51.1 (2000): 3365.

Dale, Virginia H., et al. "Climate change and forest disturbances: climate change can

affect forests by altering the frequency, intensity, duration, and timing of fire,

drought, introduced species, insect and pathogen outbreaks, hurricanes,

windstorms, ice storms, or landslides." BioScience 51.9 (2001): 723734.

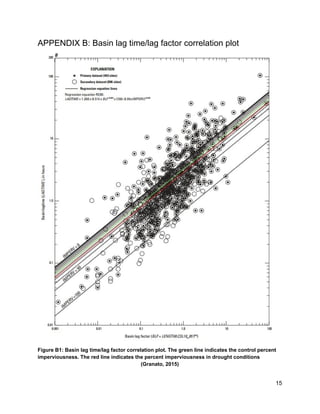

Granato, G. E. “Estimating Basin Lagtime and Hydrograph Timing Indexes Used to

Characterize Stormflows for RunoffQuality Analysis.” Reston, Virginia. 2012.

USGS. Web.

Honarbakhsh, Afshin, Seyed Javad Sadatinejad, Moslem Heydari, and Mohamadreza

Mozdianfard. "Lag Time Forecasting in a River Basin." Environmental Sciences

9.1 (2012): 47. Web. 6 Dec. 2015.

Johnson, A. I. A Field Method for Measurement of Infiltration. Washington, D.C.: U.S.

G.P.O., 1963. USGS. Web.

Liddell, Tommy. “Ventura County Watershed Protection District Planning & Regulatory

Hydrology Section Memorandum.” (2010). Web.

Mann, Michael E., and Peter H. Gleick. "Climate change and California drought in the

21st century." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112.13 (2015):

38583859.

"RMA Links." Ventura County Planning Division. Web. 2 Dec. 2015. Zoning figure

Shakesby, R. A., S. H. Doerr, and R. P. D. Walsh. "The erosional impact of soil

hydrophobicity: current problems and future research directions." Journal of

hydrology 231 (2000): 178191.

Ventura County Watershed Protection District. "VCWPD Hydrologic Data Server."

(Hydrodata). Web. 7 Dec. 2015.

Wallis, M. G., D. J. Horne, and A. S. Palmer. "Water repellency in a New Zealand

development sequence of yellow brown sands." Soil Research 31.5 (1993):

641654.

Walter, Lorraine. “Ventura River Watershed Management Plan.” (2015). Ventura River

Watershed Council. Web. 5 Dec. 2015.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/64f761e7-e6fd-4a72-90af-7035432ea5ec-160119231438/85/Writing-Sample-11-320.jpg)