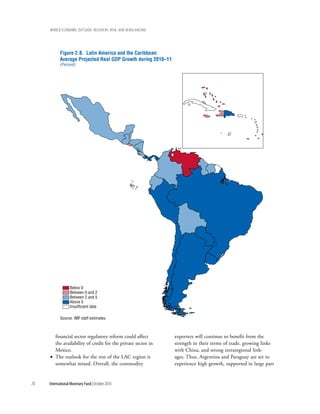

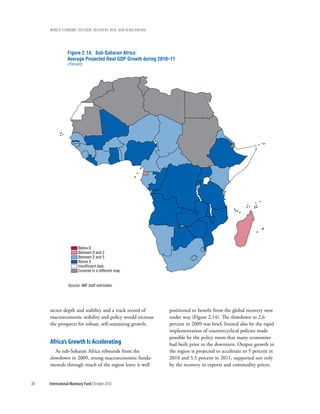

The document is the October 2010 publication of the World Economic Outlook from the International Monetary Fund. It provides an analysis of the global economic outlook and forecasts for GDP growth and inflation. The recovery from the financial crisis is ongoing but uneven across countries. Risks to the outlook include weak bank balance sheets, high unemployment, and global imbalances. More proactive fiscal and monetary policies are needed to support the recovery and rebalancing of growth.

![chapter 4 dO Financial crises Have lasting eFFects On trade??

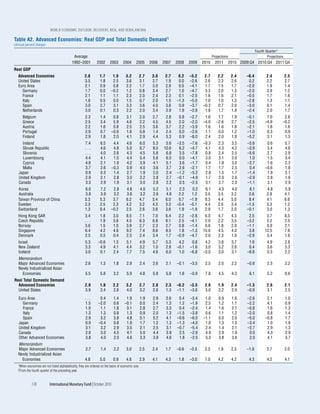

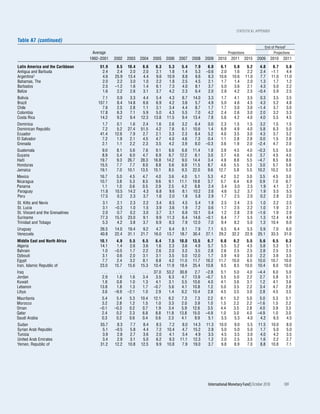

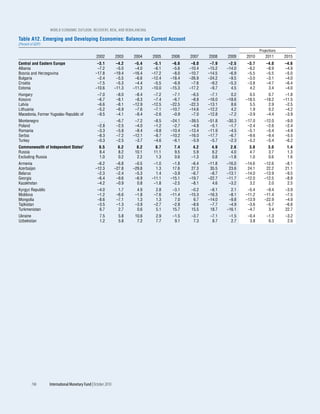

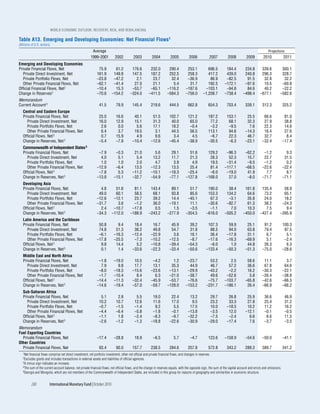

Measures included in Gregory and year” and that “much of the discrimination put in

Others (2010) place then has yet to be removed” (GTA, 2010).

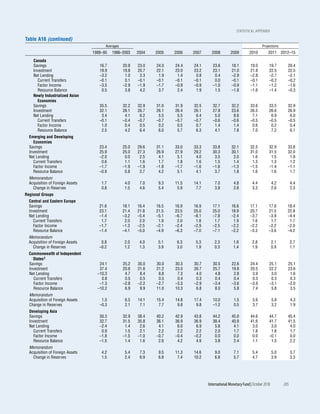

(Number of measures) Gregory and others (2010) explore the impact

Tariffs, import bans, quotas of both conventional and more unconventional

Trade defense measures “behind the border” measures highlighted in the

Nontariff barriers GTA reports, such as technical barriers to trade,

Bailouts, subsidies

procurement, and regulatory measures. The analysis

Local content, public procurement

Export measures matches data from GTA monitoring of measures

taken between mid-2008 and late 2009 with

detailed product-level data on bilateral monthly

trade flows.1 The second figure illustrates the varied

51

nature of these protectionist measures. There is

55 strong evidence that, after an economy imposed

import restrictions on a particular product, its

imports fell in succeeding months relative to world

trade in the same product (third figure). Allowing

for various time-varying fixed effects, more sophis-

ticated econometric analysis suggests that trade in

16

the affected products dropped an average of 3 to 8

1Extending the data set through May 2010 does not

substantially change the results of the analysis.

21 14

27

Bilateral Trade Flows subject to Measures

Implemented in November 2008

(Index, October 2008 = 100)

Source: Global Trade Alert Database.

120

to see, an extreme protectionist surge like that of

100

the 1930s, but their assessments differ markedly.

The June 2010 joint report of the WTO, Organiza-

tion for Economic Cooperation and Development 80

(OECD), and United Nations Conference on

Trade and Development (unctad) indicates that

60

“protectionist policy responses have been limited,

although there are still instances of restrictive mea-

sures taken… [T]here continues to be few instances 40

of new import restrictions and a greater use of

export restrictions, but some G20 governments

20

have also taken steps to facilitate trade” (WTO,

OECD, and unctad, 2010). In contrast, the sixth

report of Global Trade Alert (GTA), which is asso- 0

2008 09 09 09 09

ciated with the London-based Centre for Economic

Nov. Feb. May Aug. Nov.

Policy Research and supported by the World Bank,

also released in June 2010, concludes that “as far as Source: IMF staff calculations.

open markets were concerned, 2009 was a terrible

International Monetary Fund | October 2010 147](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/worldeconomicoutlook2010imf-101012111544-phpapp02/85/World-economic-outlook-2010-imf-165-320.jpg)

![chapter 4 dO Financial crises Have lasting eFFects On trade??

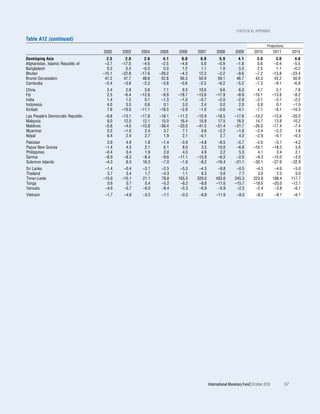

lands Bureau of Economic Policy Analysis for the following a crisis.26 In contrast to the baseline,

remaining products—and are seasonally adjusted. this methodology allows for an episode-specific

The HS four-digit codes are matched to the BEC trend, as opposed to the country-specific trend

and classified into Capital Goods, Consumer that is captured by ai in the baseline specifica-

Durables, Consumer Nondurables, Intermediate tion. However, it does not control for global

Goods, and Primary Goods, following Pula and conditions as is done in the baseline.

Peltonen (2009). • Alternative 2: Baseline specification with autore-

gressive terms—The baseline specification is

augmented by including four lags of the growth

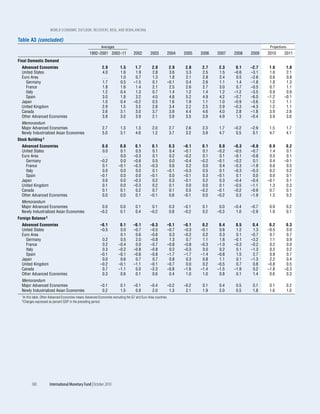

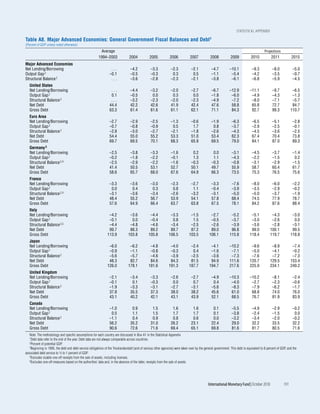

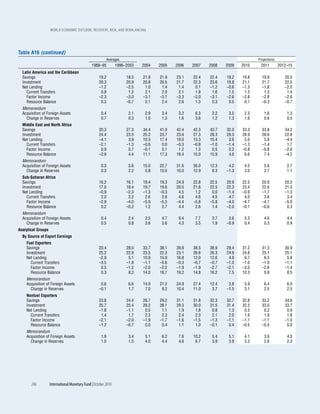

appendix 4.2. Methodology and robustness of imports on the right-hand side, paralleling the

tests specifications used in Romer and Romer (2010)

estimating Unconditional import losses and Cerra and Saxena (2008):

The analysis25 first estimates the unconditional D ln Mit 5 ai 1 pt 1 ∑ rl D ln Mi,t–1

dynamics of imports in the aftermath of crises using

a “collapsed” gravity model of trade in changes. 1 ∑ ak crisisi,t–k 1 eit. (4.3)

In the baseline regression specification in the text, • Alternative 3: Bilateral gravity in changes—A

the growth in an economy’s aggregate imports, directional gravity model (that is, one with bilat-

D ln Mit , is expressed as a function of a dummy eral imports or exports as opposed to bilateral

variable indicating whether a crisis started in year t, trade) is estimated in changes. The growth in

five lags of this dummy variable, and country and bilateral imports of an economy from each trad-

time dummies: ing partner, D ln Mimp,exp,t, is regressed on a crisis

D ln Mit 5 ai 1 pt 1 ∑ ak crisisi,t–k 1 eit. (4.1) indicator and its lags, as well as on time and

importer-exporter pair dummies:

The robustness of the estimated unconditional

import losses from the baseline specification is D ln Mimp,exp,t 5 aimp,exp 1 pt

verified by using the following five alternative 1 ∑ a'k crisisimp,t–k 1 eimp,exp,t . (4.4)

specifications:

• Alternative 1: Deviation from precrisis trend— • Alternative 4: Bilateral gravity in changes, using top

This procedure measures import loss as a simple 20 partners—This specification is identical to the

deviation of ln Mit from a precrisis trend, ln Trit, directional gravity model in changes as described

where the latter is a linear trend based on a in equation (4.4) but focuses only on the top

precrisis window from (t – 7) to (t – 1). The 20 partners from which an economy imports.

mean import loss k years after a crisis is just the This is done because our primary concern is in

average of this import loss, (ln Mit – ln Trit), describing the behavior of aggregate trade, rather

across all crisis episodes. This is equivalent to than average bilateral trade. The standard gravity

estimating the following equation, either in levels model weights all bilateral trade observations

or changes: equally, regardless of the size of the bilateral trade

ln Mit 2 ln Trit 5 ∑ bk crisisi,t–k 1 eit. (4.2)

26The results from estimating equation (4.2) in levels or

This procedure is similar to the procedure changes are identical because, as in Chapter 4 of the October

2009 World Economic Outlook, the import losses are normalized

used in Chapter 4 of the October 2009 World so that the loss in the year before the crisis (t – 1) is zero. The

Economic Outlook for estimating output losses primary differences between the procedure used here and in

Chapter 4 of the October 2009 World Economic Outlook are the

following: (1) the definition of crisis (debt crises combined with

banking crises versus banking crises only), (2) the precrisis win-

25We focus on import dynamics here, since the chapter’s dow used to calculate the trend [(t – 7) to (t – 1) versus (t – 10)

results suggest that imports are where the impact of a crisis on to (t – 3)], and (3) the choice of dependent variable (imports

trade is primarily manifested. versus GDP per capita).

International Monetary Fund | October 2010 151](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/worldeconomicoutlook2010imf-101012111544-phpapp02/85/World-economic-outlook-2010-imf-169-320.jpg)

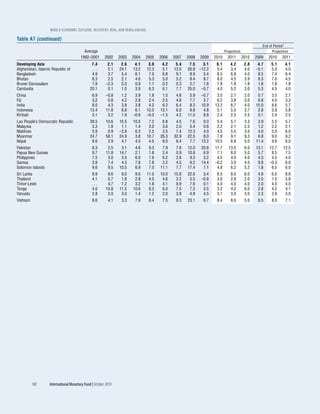

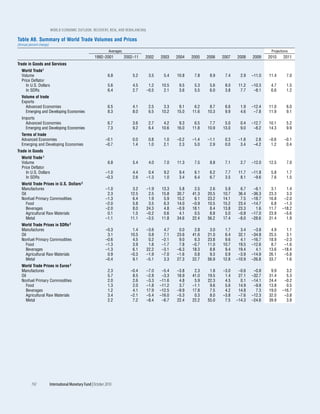

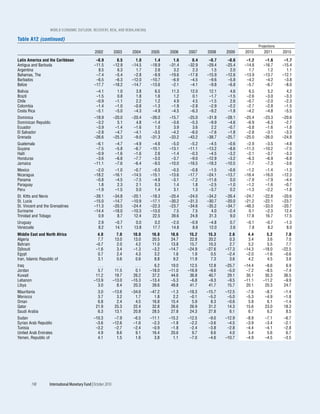

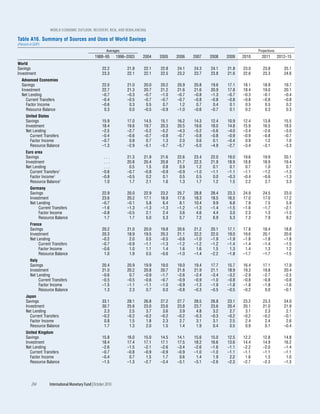

![Selected tOpicS

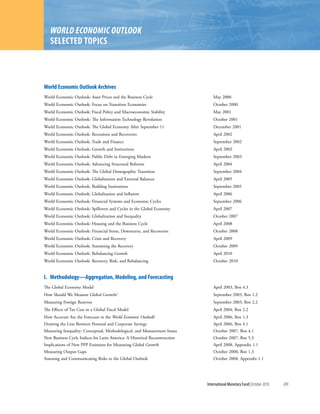

When Does Fiscal Stimulus Work? April 2008, Box 2.1

Fiscal Policy as a Countercyclical Tool October 2008, Chapter 5

Differences in the Extent of Automatic Stabilizers and Their Relationship

with Discretionary Fiscal Policy October 2008, Box 5.1

Why Is It So Hard to Determine the Effects of Fiscal Stimulus? October 2008, Box 5.2

Have the U.S. Tax Cuts been “TTT” [Timely, Temporary, and Targeted]? October 2008, Box 5.3

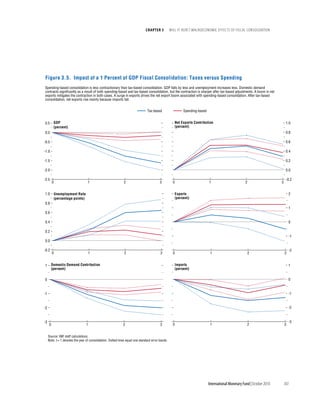

Will It Hurt? Macroeconomic Effects of Fiscal Consolidation October 2010, Chapter 3

Vi. Monetary policy, Financial Markets, and Flow of Funds

When Bubbles Burst April 2003, Chapter 2

How Do Balance Sheet Vulnerabilities Affect Investment? April 2003, Box 2.3

Identifying Asset Price Booms and Busts April 2003, Appendix 2.1

Are Foreign Exchange Reserves in Asia Too High? September 2003, Chapter 2

Reserves and Short-Term Debt September 2003, Box 2.3

Are Credit Booms in Emerging Markets a Concern? April 2004, Chapter 4

How Do U.S. Interest and Exchange Rates Affect Emerging Markets’

Balance Sheets? April 2004, Box 2.1

Does Financial Sector Development Help Economic Growth and Welfare? April 2004, Box 4.1

Adjustable- or Fixed-Rate Mortgages: What Influences a Country’s Choices? September 2004, Box 2.2

What Are the Risks from Low U.S. Long-Term Interest Rates? April 2005, Box 1.2

Regulating Remittances April 2005, Box 2.2

Financial Globalization and the Conduct of Macroeconomic Policies April 2005, Box 3.3

Monetary Policy in a Globalized World April 2005, Box 3.4

Does Inflation Targeting Work in Emerging Markets? September 2005, Chapter 4

A Closer Look at Inflation Targeting Alternatives: Money and

Exchange Rate Targets September 2005, Box 4.1

How Has Globalization Affected Inflation? April 2006, Chapter 3

The Impact of Petrodollars on U.S. and Emerging Market Bond Yields April 2006, Box 2.3

Globalization and Inflation in Emerging Markets April 2006, Box 3.1

Globalization and Low Inflation in a Historical Perspective April 2006, Box 3.2

Exchange Rate Pass-Through to Import Prices April 2006, Box 3.3

Trends in the Financial Sector’s Profits and Savings April 2006, Box 4.2

How Do Financial Systems Affect Economic Cycles? September 2006, Chapter 4

Financial Leverage and Debt Deflation September 2006, Box 4.1

Financial Linkages and Spillovers April 2007, Box 4.1

Macroeconomic Conditions in Industrial Countries and Financial Flows to

Emerging Markets April 2007, Box 4.2

What Is Global Liquidity? October 2007, Box 1.4

Macroeconomic Implications of Recent Market Turmoil: Patterns from

Previous Episodes October 2007, Box 1.2

The Changing Housing Cycle and the Implications for Monetary Policy April 2008, Chapter 3

Assessing Vulnerabilities to Housing Market Corrections April 2008, Box 3.1

Is There a Credit Crunch? April 2008, Box 1.1

International Monetary Fund | October 2010 213](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/worldeconomicoutlook2010imf-101012111544-phpapp02/85/World-economic-outlook-2010-imf-231-320.jpg)