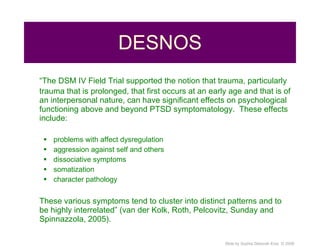

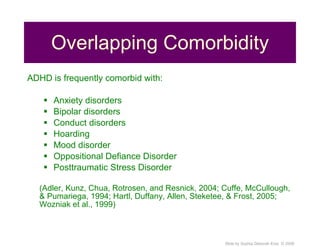

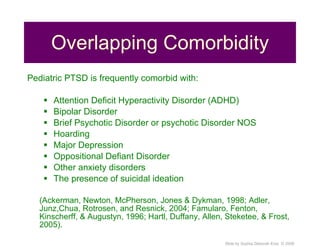

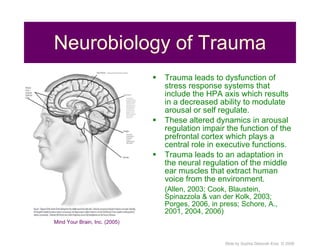

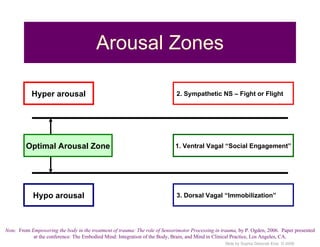

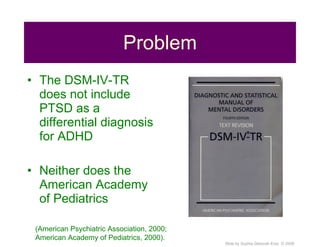

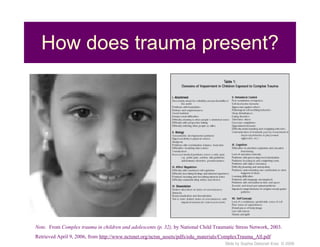

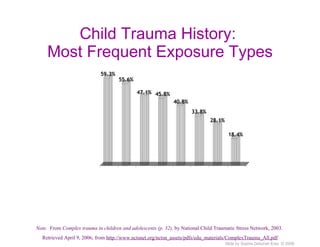

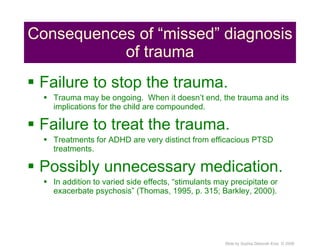

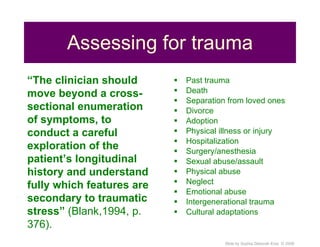

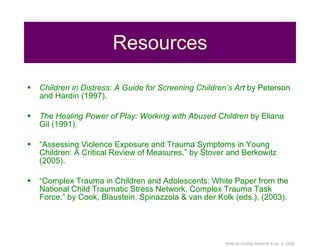

This document discusses the importance of considering trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as potential differential diagnoses when a child presents with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It notes that trauma, especially prolonged or interpersonal trauma at a young age, can produce effects that overlap with ADHD symptoms. Assessing for a history of trauma is crucial to properly diagnose and treat the child's symptoms. Misdiagnosing trauma as ADHD could result in ongoing trauma if the root cause is not addressed, as well as unnecessary medication without treating the underlying trauma.