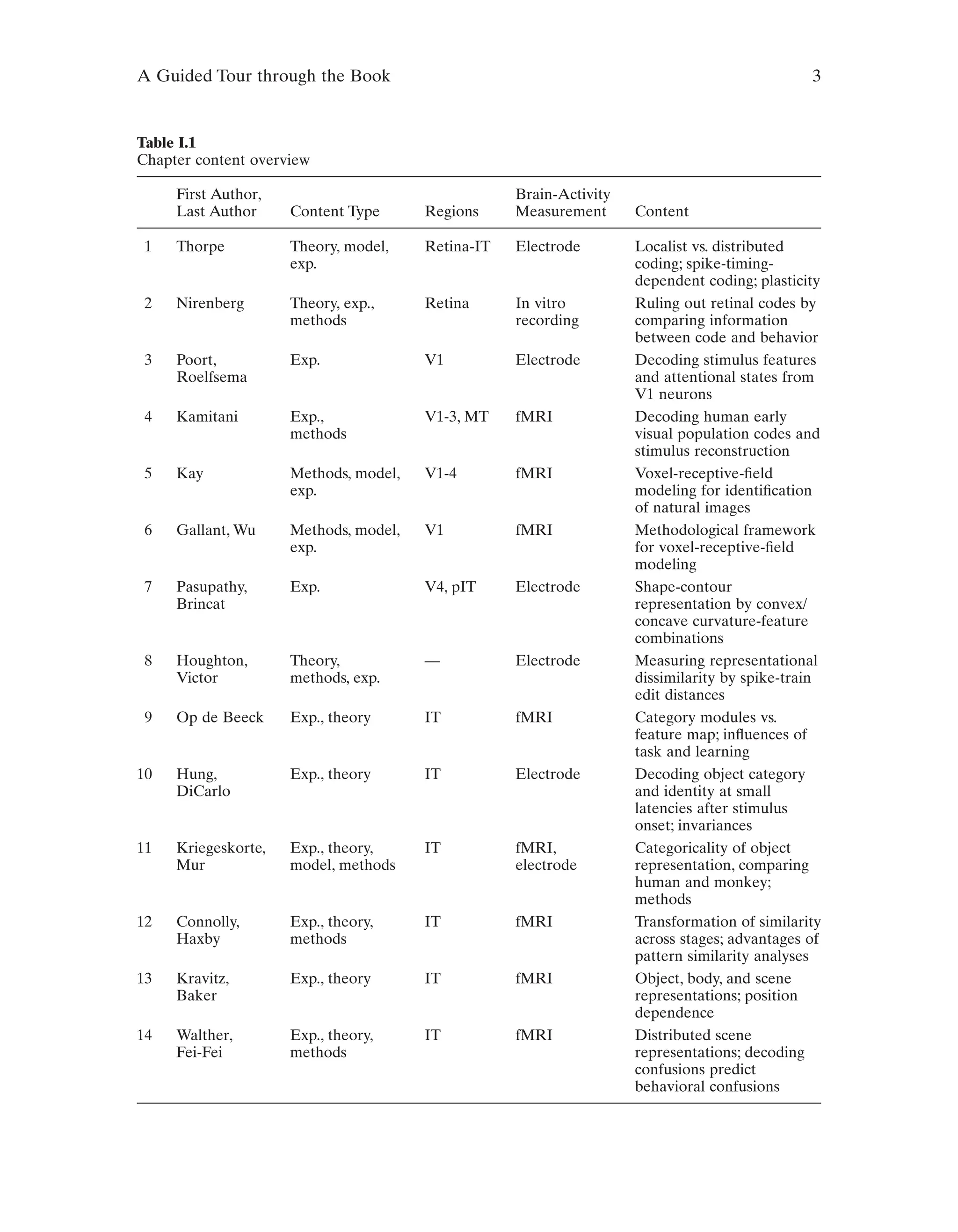

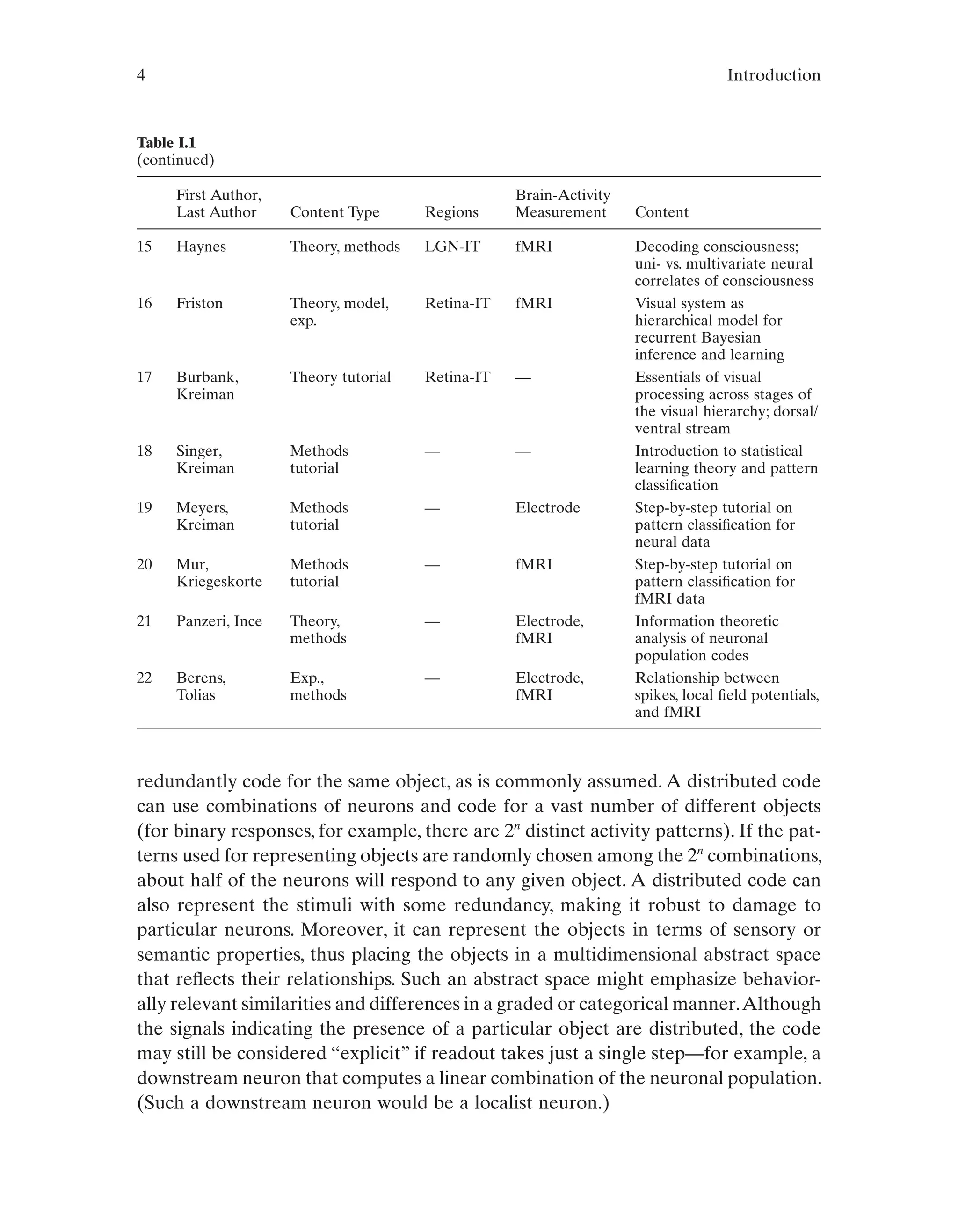

Visual Population Codes Toward A Common Multivariate Framework For Cell Recording And Functional Imaging Edited By Nikolaus Kriegeskorte Gabriel Kreiman

Visual Population Codes Toward A Common Multivariate Framework For Cell Recording And Functional Imaging Edited By Nikolaus Kriegeskorte Gabriel Kreiman

Visual Population Codes Toward A Common Multivariate Framework For Cell Recording And Functional Imaging Edited By Nikolaus Kriegeskorte Gabriel Kreiman