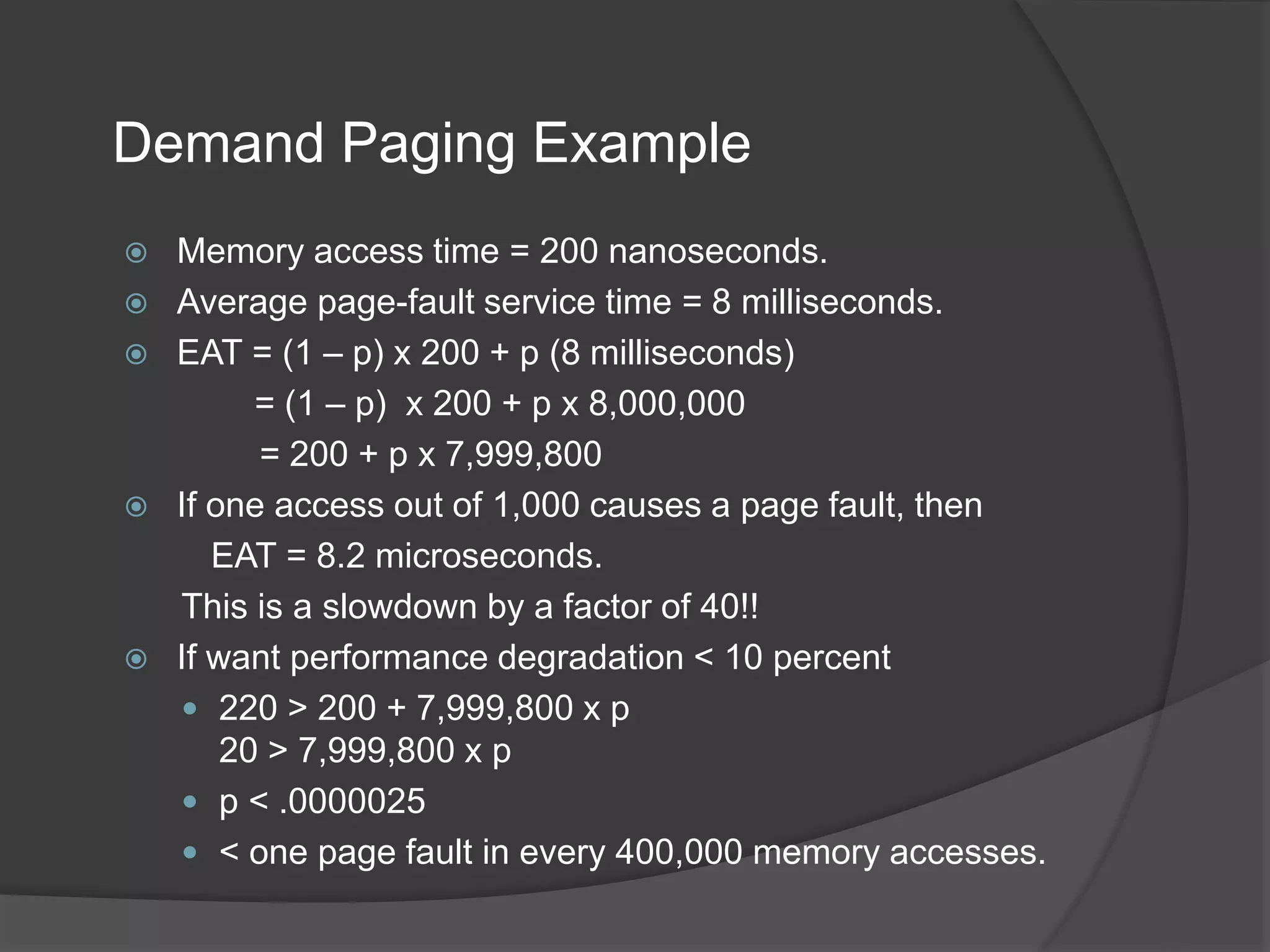

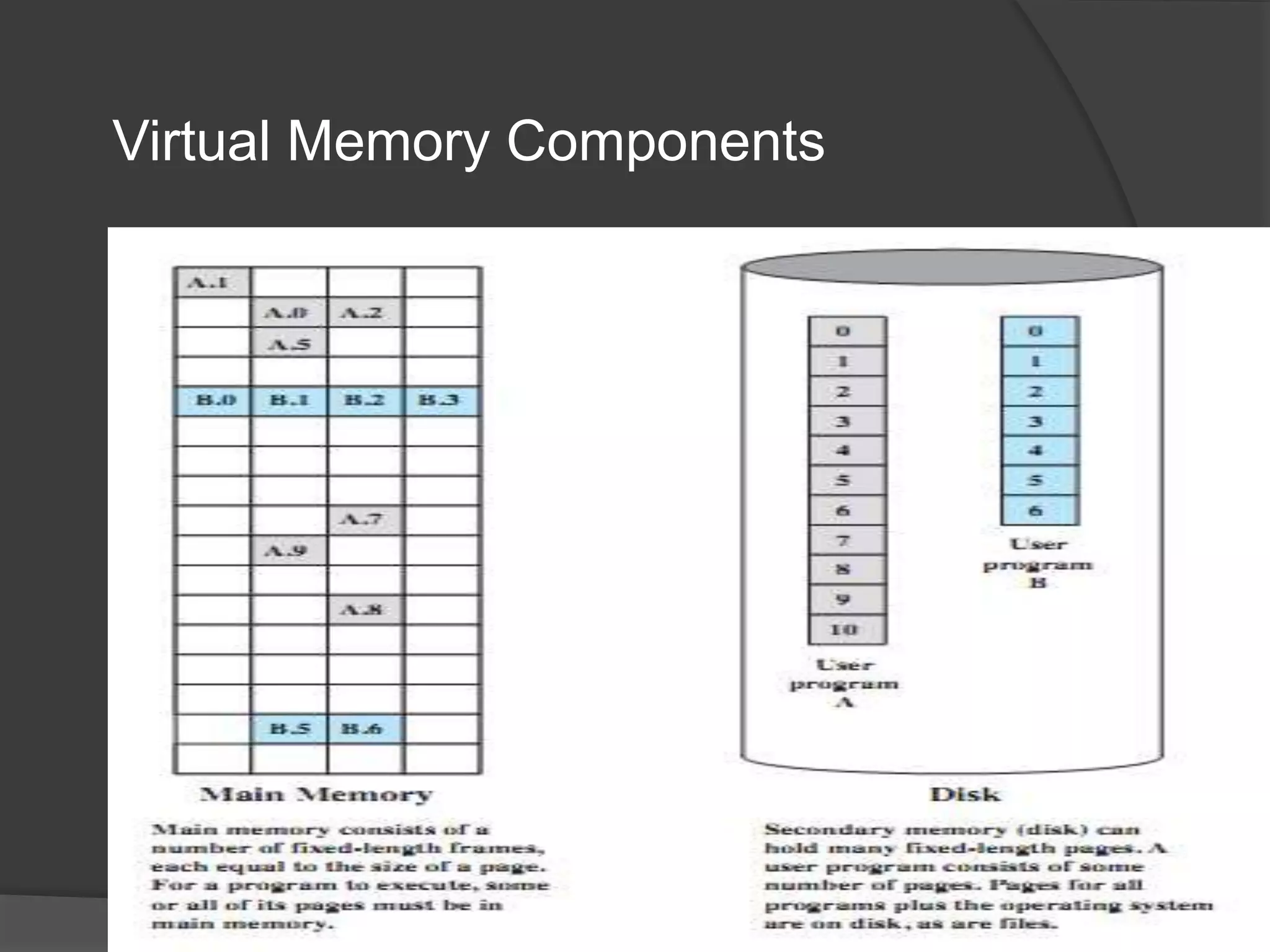

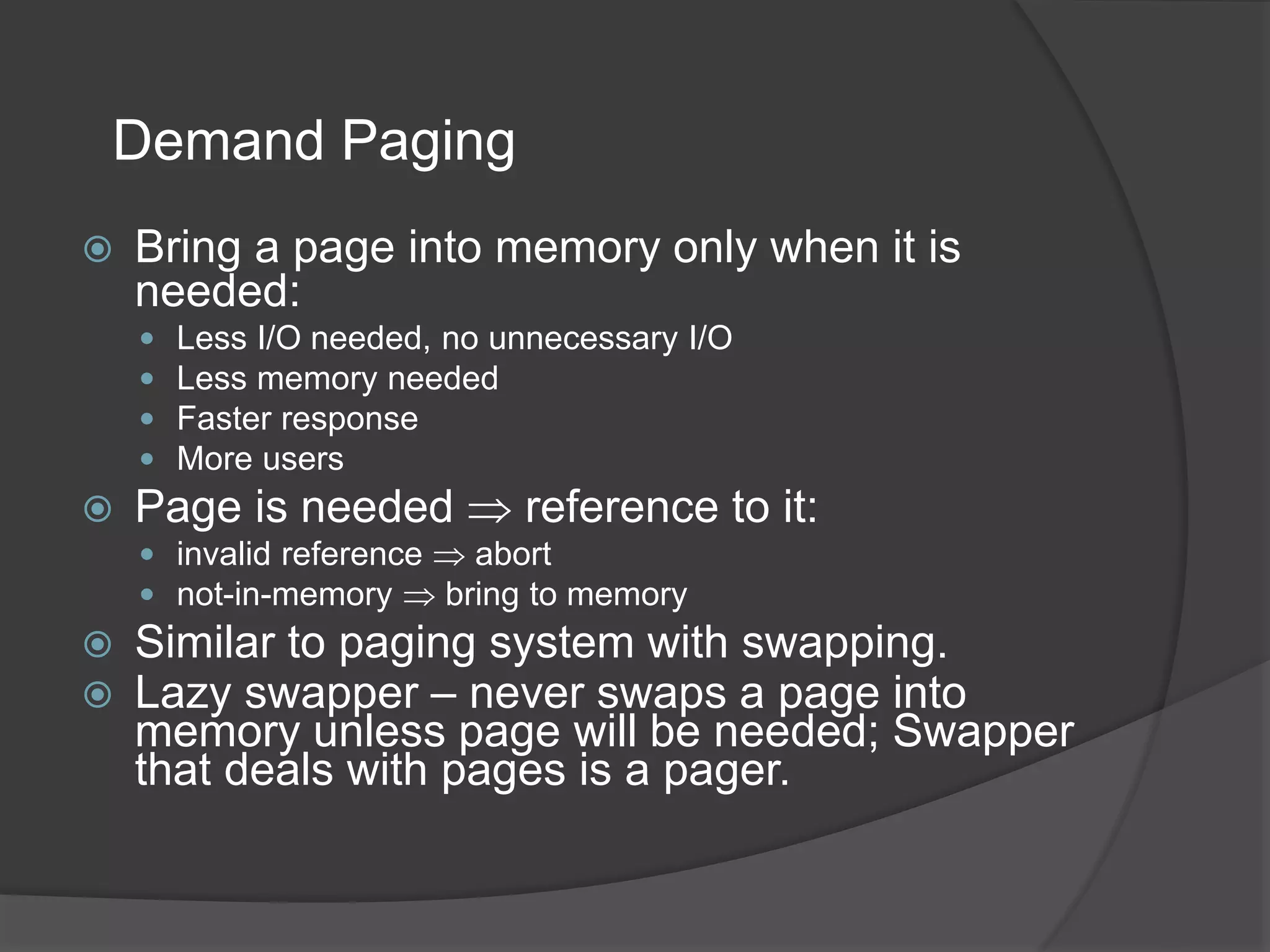

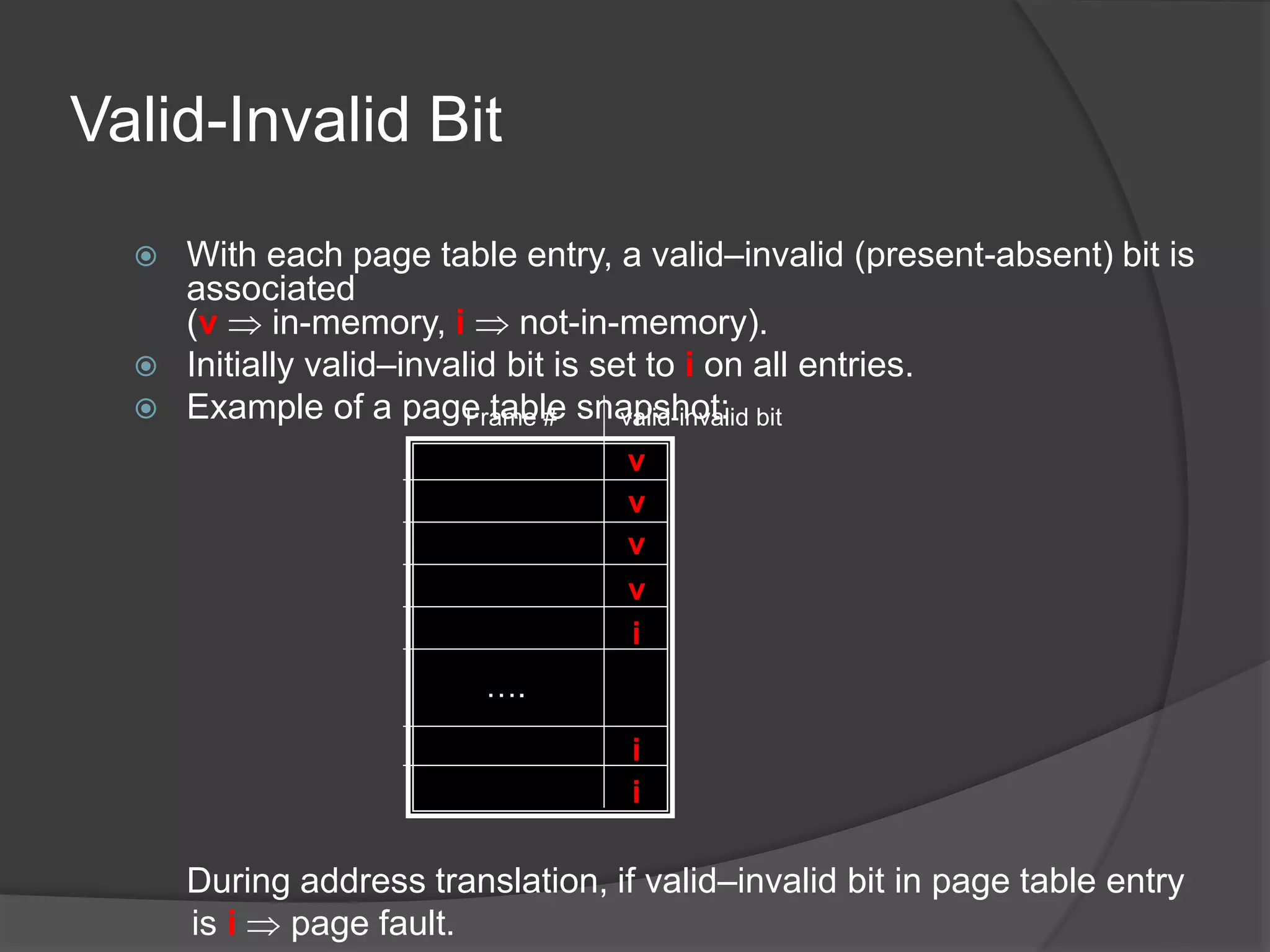

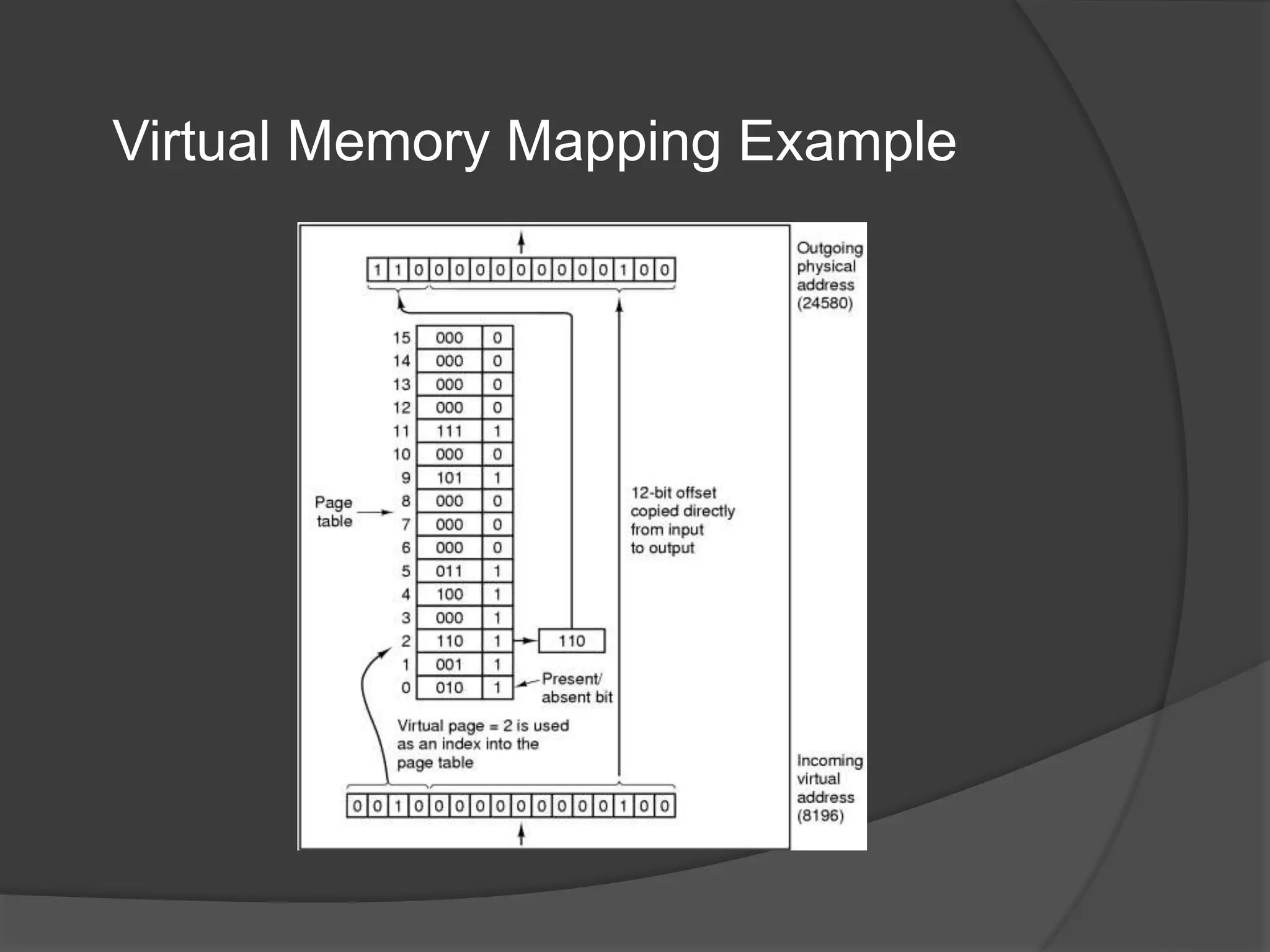

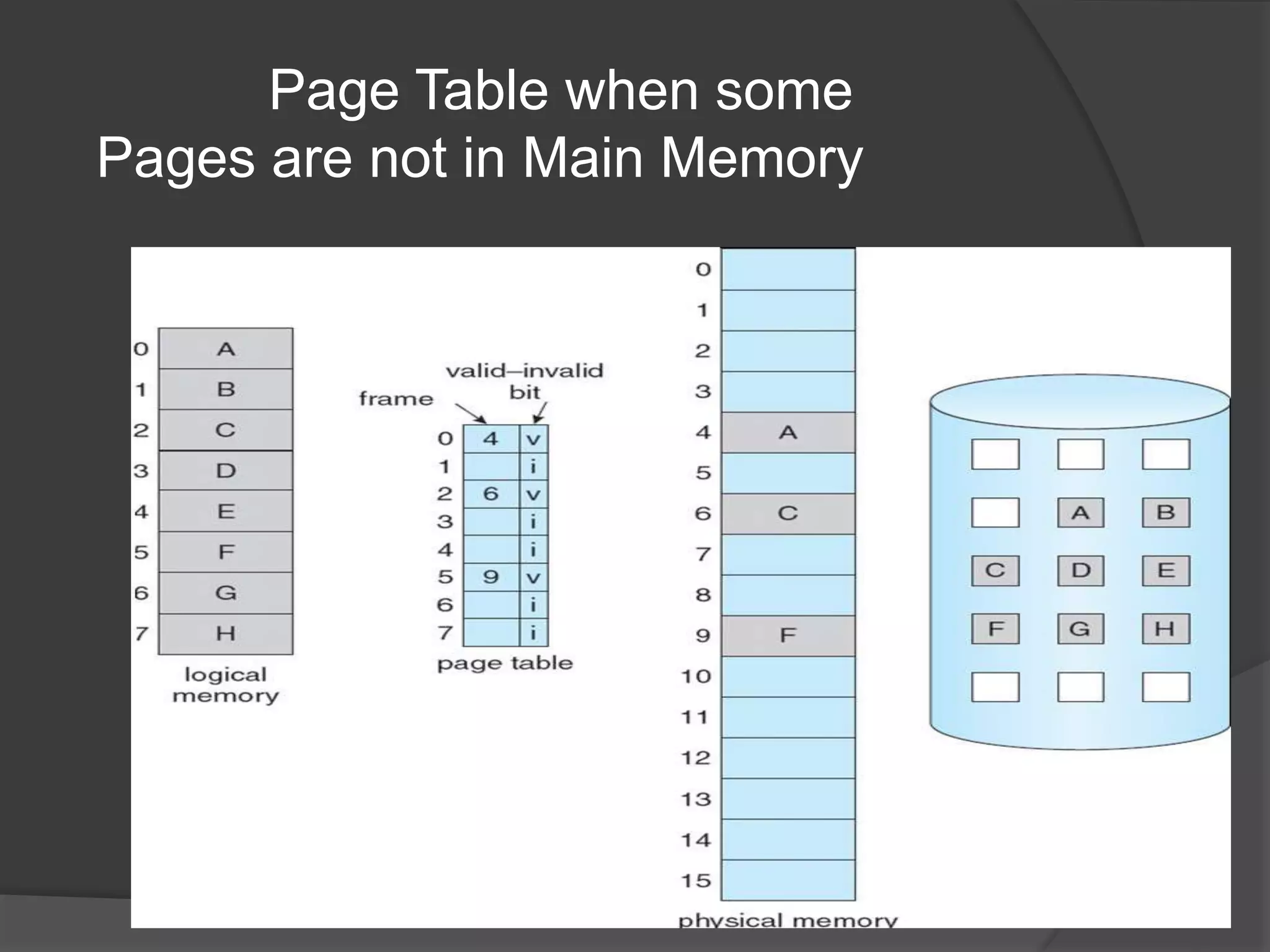

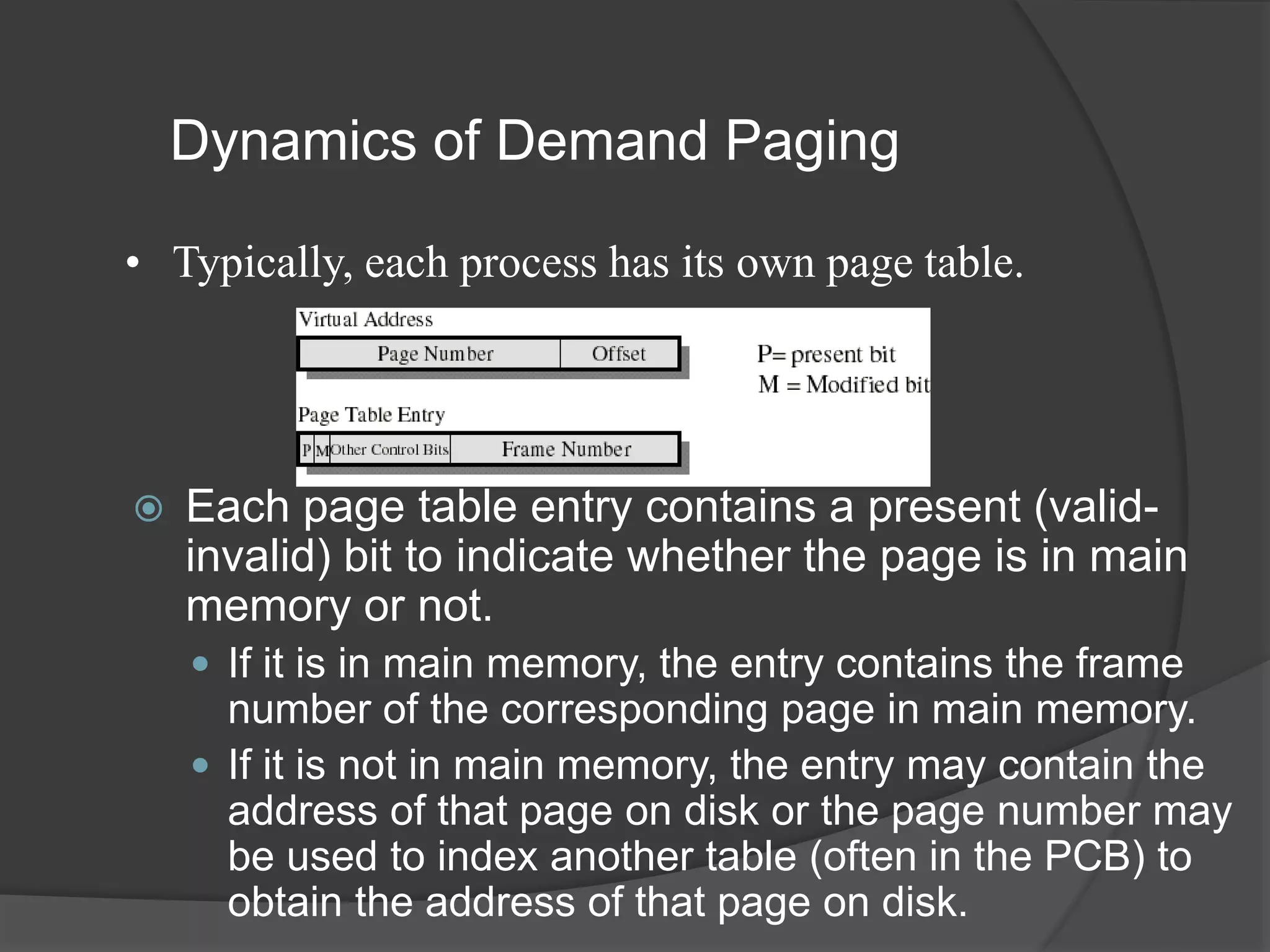

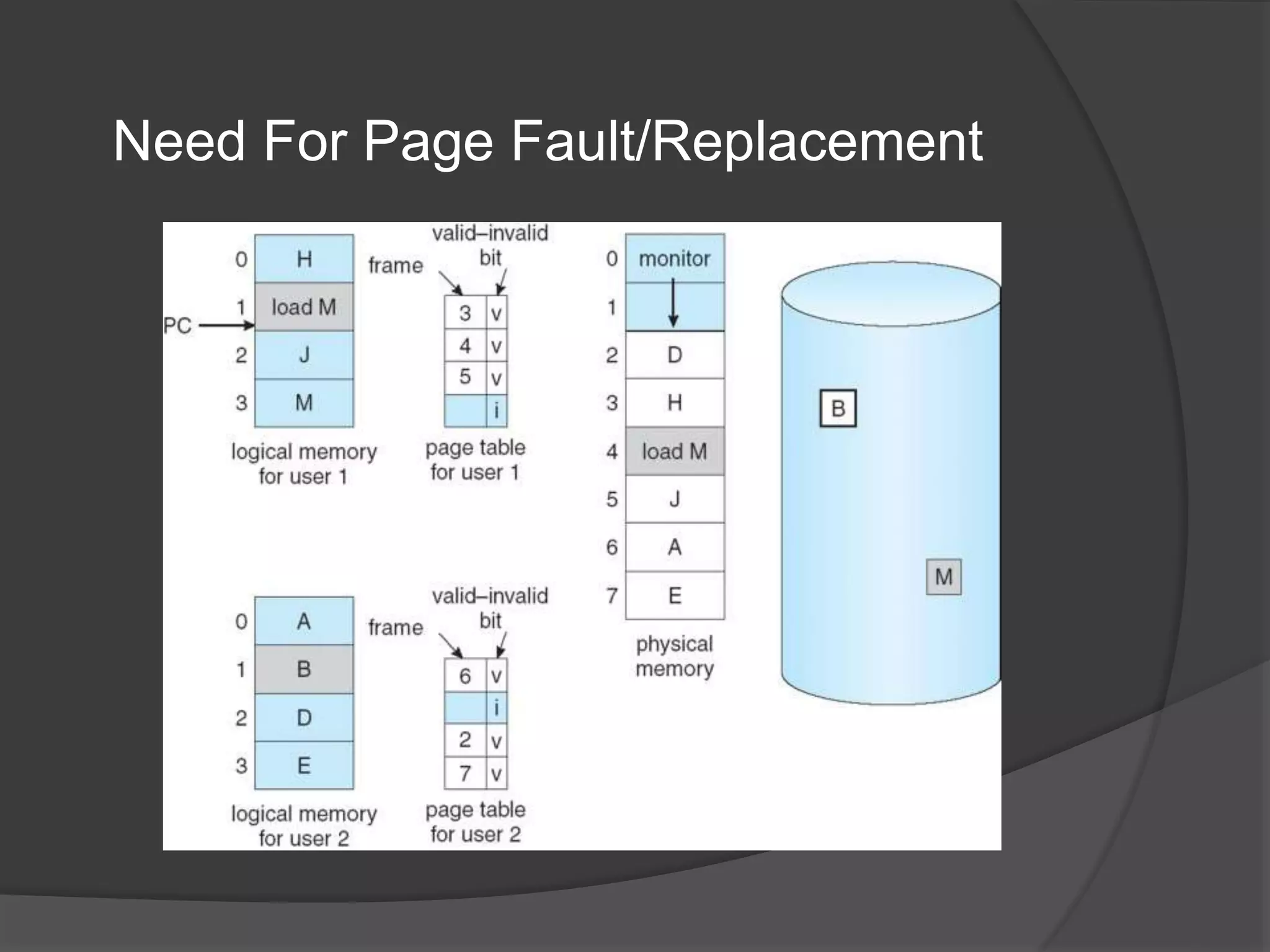

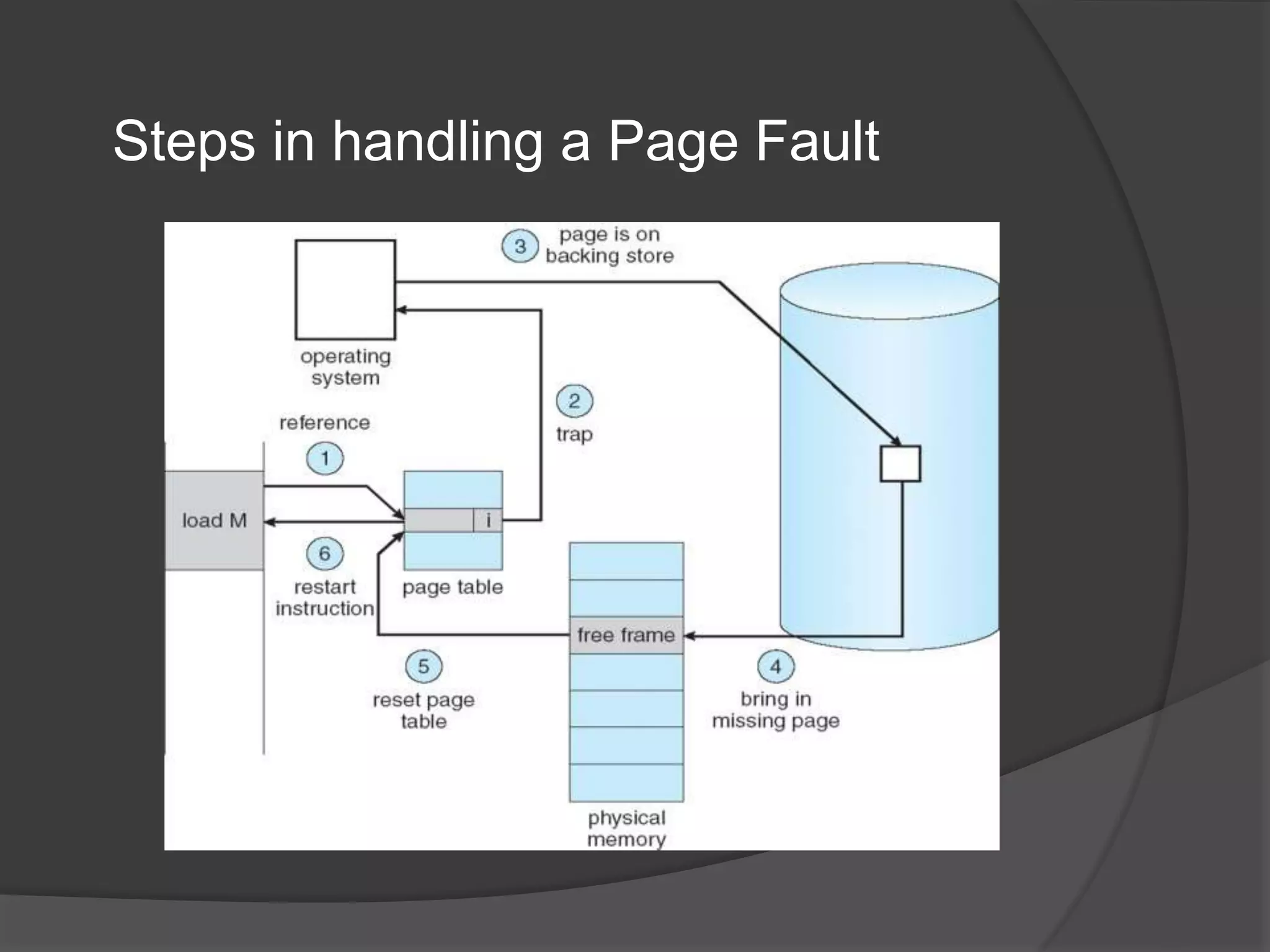

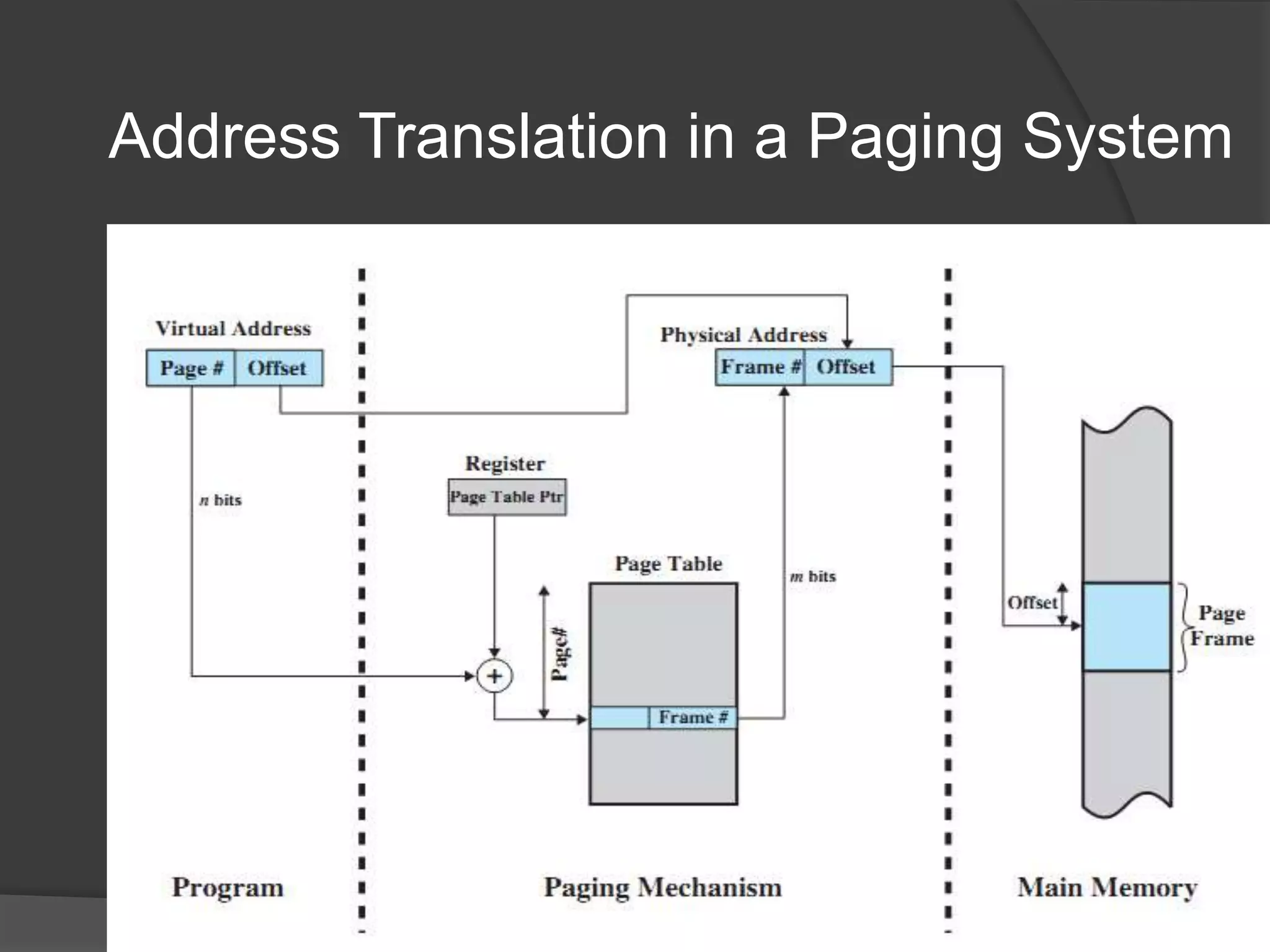

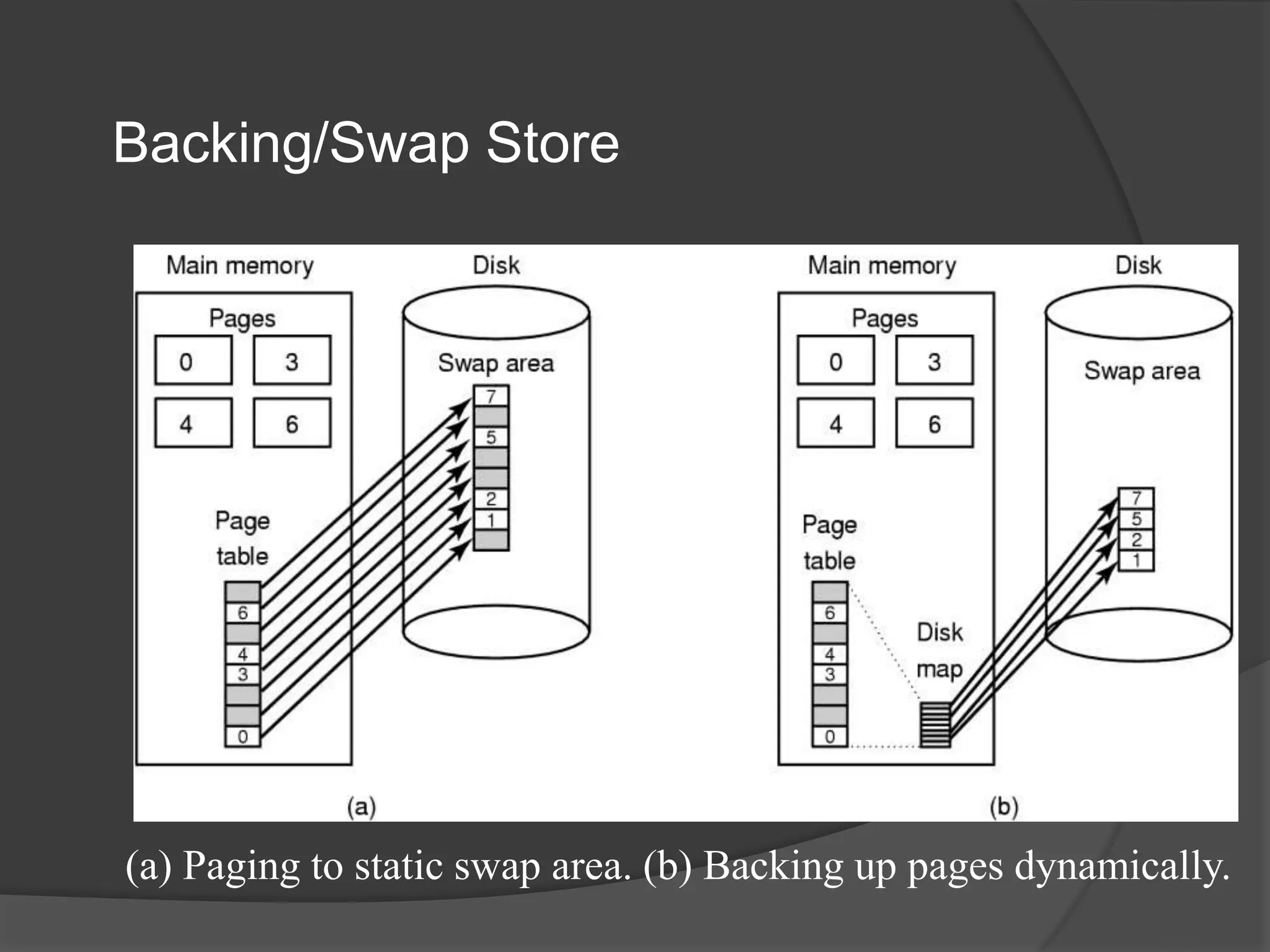

Virtual memory uses demand paging to load pages into physical memory only when needed by the process. During address translation, if the valid-invalid bit in the page table entry is invalid, a page fault occurs which triggers loading the missing page from disk into physical memory. The hardware must support features like page tables, secondary storage, and instruction restart to implement demand paging transparently. While demand paging reduces I/O, each page fault incurs significant overhead which can degrade performance if the page fault rate is too high.

![Performance of Demand Paging

Three major activities:

Service the interrupt – careful coding means just several hundred

instructions needed.

Read the page – lots of time..

Restart the process – again just a small amount of time

Page Fault Rate 0 p 1

if p = 0, no page faults.

if p = 1, every reference is a fault.

Effective Access Time (EAT) –

EAT = (1 – p) x memory access

+ p x (page fault overhead

+ [swap page out]

+ swap page in

+ restart overhead)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/virutualmemory-demandpaging-200313163554/75/Virtual-memory-Demand-Paging-24-2048.jpg)