This document discusses contemporary psychodynamic models of personality, focusing on object-relations theory, self psychology, and ego psychology, and their influence on understanding personality development. Key concepts include the impact of early attachment relationships on individual psychology, the nature of narcissism, and the significance of maternal and paternal figures. The chapter emphasizes the effects of early separation and attachment disruptions on later psychological issues, supported by research in both humans and nonhuman species.

![shape our behavior and our personality.

• Drives are “[s]trong stimuli which impel action” (Dollard &

Miller, 1950, p. 30). Unlearned

drives, such as hunger, thirst, sex, fatigue, and pain, are labeled

primary drives. The

strength of the primary drives is related to the degree of

deprivation: The longer you have

been without food or sex, the stronger your hunger or sex drive.

Learned drives, such as

those related to fear or the need for approval, are termed

secondary drives. The notion of

secondary drives provided far greater explanatory power than

did the concept of primary

drives alone, and this was especially important in the attempt to

provide a comprehensive

explanation of human personality and the development of

neurosis.

• Cues are stimuli that direct attention to certain aspects of the

environment. They deter-

mine what we will respond to and how. For example, internal

hunger cues or the golden

arches direct our attention toward food.

• Response: Under certain drive conditions (for example, strong

hunger) we respond to

cues (we eat when we have the banana in front of us).

Responses can be weak at first,

explain Dollard and Miller, but reinforcement can strengthen

them. In addition, a variety

of different responses are possible in a given situation. In a

sense, there are hierarchies of

responses. Some are more likely (i.e., more “dominant”) than

others. Among the various

ways in which habits are acquired, they suggest that trial and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viktorcapistockthinkstocklearningobjectivesafterr-221013111410-b9b62701/75/ViktorCapiStockThinkstockLearning-Objectives-After-r-docx-273-2048.jpg)

![(REBT)] was one of the earliest applications of the cognitive

model to psychotherapy. It emerged

in the mid-1950s (Ellis & Harper, 1961) and was at the

forefront of the cognitive revolution. Ellis

claims that REBT “had an implicit theory of personality” (Ellis,

1974, p. 309). A later text, published

shortly after his death in 2007, at age 90, presented a more

formal theory of personality (Ellis,

Abrams, & Abrams, 2009).

Ellis’s basic tenet is that irrational thinking (a decidedly

cognitive event) is the central cause of

human suffering. His theory is partly derived from the work of

Alfred Adler (1923), who believed

that humans constantly evaluate and give meaning to events in

their lives. Ellis acknowledges the

influence of Karen Horney (1950), who talked about the

“tyranny of shoulds” (as in “I should have

done that,” “I should act like this,” etc.). He also was

influenced by the work of Julian Rotter (1954),

who emphasized the cognitive aspects of learning and

personality theory (Arnkoff & Glass, 1992).

More specifically, Ellis believed that it is not the actions of

others, the defeats we experience, the

problems of the external world, or other events that cause](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viktorcapistockthinkstocklearningobjectivesafterr-221013111410-b9b62701/75/ViktorCapiStockThinkstockLearning-Objectives-After-r-docx-640-2048.jpg)

![· Iurato, G. (2015). A brief comparison of the unconscious as

seen by Jung and Lévi-Strauss [PDF file]. Anthropology of

Consciousness, 26(1), 60-107.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/anoc.12032

· Kealy, D., Steinberg, P. I., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S.

(2015). “Difficult” patient? Or is it a personality

disorder?Clinician Reviews, 25(2), 40-46. Retrieved from

https://www.mdedge.com/clinicianreviews

· Lerner, H. (2013, March 5). Become successful by

understanding peoples personalities (Links to an external site.).

Retrieved from

https://www.forbes.com/sites/hannylerner/2013/03/05/understan

d-peoples-personalities-and-become-successful/#1f1c9fda6701

· Palacios, E. G., Echaniz, I. E., Fernández, A. R., & de Barrón,

I. C. O. (2015). Personal self-concept and satisfaction with life

in adolescence, youth, and adulthood.Psicothema,27(1), 52-58.

http://dx/doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2014.105

· Stahl, A. (2017, April 30). 3 ways knowing your personality

type can help you with your career (Links to an external site.).

Retrieved from

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ashleystahl/2017/04/30/3-ways-

knowing-your-personality-type-can-help-you-with-your-

career/#311ed4c43a33

· Weaver, I. C. G., Cervoni, N., Champagne, F. A., D’Alessio,

A. C, Sharma, S., Seckl, J. R., … Meaney, M. J.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viktorcapistockthinkstocklearningobjectivesafterr-221013111410-b9b62701/75/ViktorCapiStockThinkstockLearning-Objectives-After-r-docx-923-2048.jpg)

![(2004). Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature

Neuroscience, 7(8), 847-854. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nn1276

· Webster, M. (2013, January 10). The great rat mother

switcheroo (Links to an external site.) [Blog post]. Retrieved

from http://www.radiolab.org/story/261176-

· Weck, F. (2014). Treatment of mental hypochondriasis: A case

report. Psychiatric Quarterly,85(1), 57-64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11126-013-9270-6

·

Multimedia

· Harris, B. [Brooke Harris]. (2009, April 17). Sigmund Freud:

The unconscious mind (short version) (Links to an external

site.) [Video file]. Retrieved https://youtu.be/R0w0db2zR7Q

· Truity. (n.d.). The big five personality test (Links to an

external site.) [Measurement instrument]. Retrieved from

http://www.truity.com/test/big-five-personality-test

· WNYC Studios. (2012, November 18). Inheritance (Links to

an external site.) [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from

https://www.wnycstudios.org/story/251876-inheritance

Web Pages

· Lebon, T. (2012, February 5). CBT and behavioural

experiments (Links to an external site.). [Blog post]. Retrieved

from http://cbtfortherapists.blogspot.com/2012/02/cbt-and-

behavioural-experiments.html

· Lebon, T. (2009, September 27). Giving a rationale for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viktorcapistockthinkstocklearningobjectivesafterr-221013111410-b9b62701/75/ViktorCapiStockThinkstockLearning-Objectives-After-r-docx-924-2048.jpg)

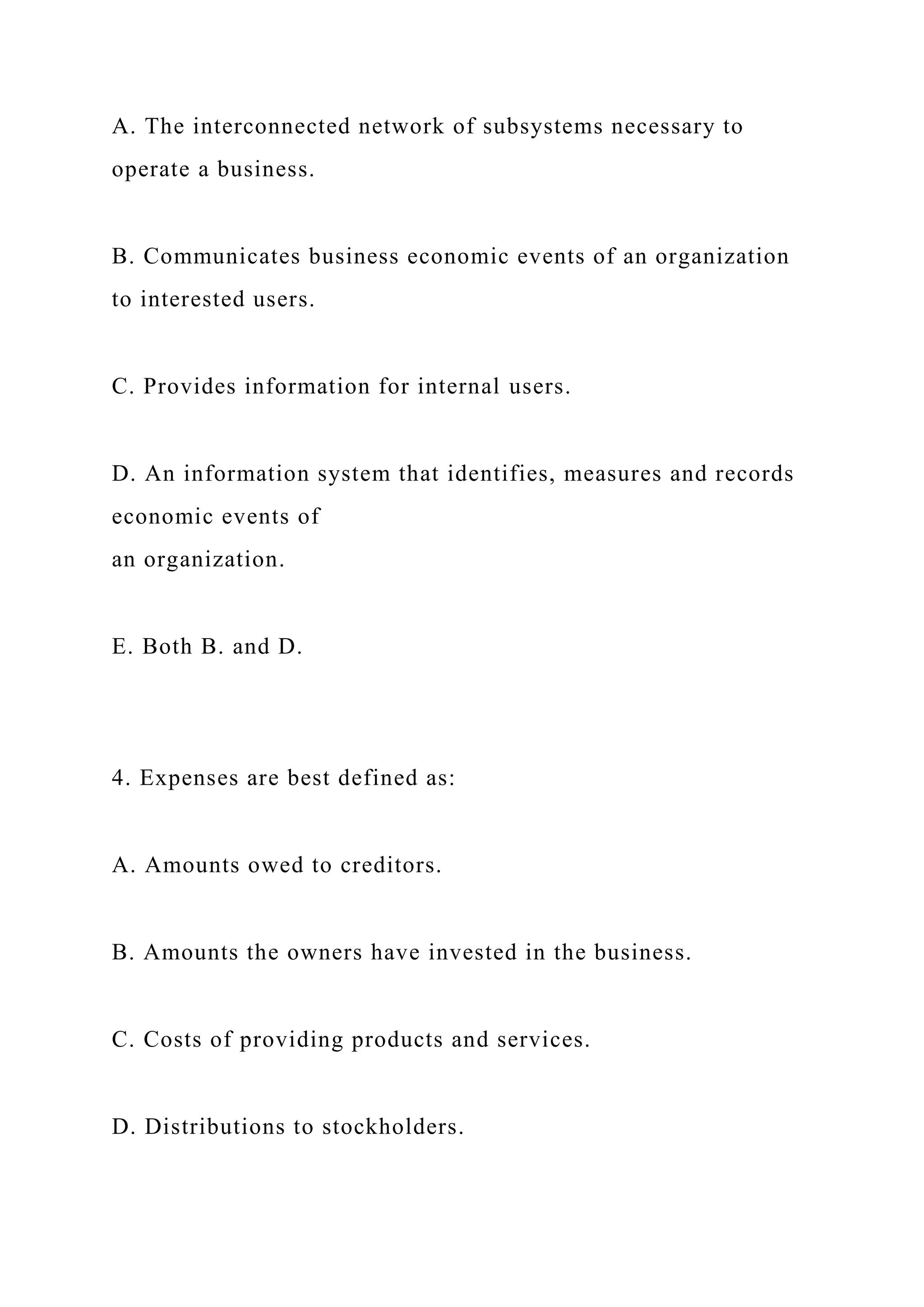

![CBT (Links to an external site.) [Blog post]. Retrieved from

http://cbtfortherapists.blogspot.com/2009/09/giving-rationale-

for-cbt.html

·

SPRING 2020 Exam 1 Version 1

Last Name:

First Name:

Student ID:

Circle Section #

Section # Class Time

1 9:10pm

2 1:10pm

3 2:10am

Instructions:

1. On your scantron: Fill in your Last Name, space, First Name,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/viktorcapistockthinkstocklearningobjectivesafterr-221013111410-b9b62701/75/ViktorCapiStockThinkstockLearning-Objectives-After-r-docx-925-2048.jpg)