This document provides an introduction to vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP). It discusses how VEMP responses in muscles like the sternocleidomastoid muscle can be elicited by sound, vibration, or electrical stimulation and assessed clinically. While early studies recorded potentials from the inion, the current clinical form of VEMP testing utilizes biphasic responses recorded from the sternocleidomastoid muscle. VEMP testing was established as a method to assess saccular function after studies found the responses disappeared on the affected side after unilateral vestibular nerve section. Further research has since clarified that sound stimulation of the saccule is conveyed by the inferior vestibular nerve, making VEMP a useful

![Introduction

Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP) are responses in the muscles,

especially cervical muscles such as the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), to

sound, vibration, or electrical stimulation (Fig. 1). Because it seemed that VEMP

could be used for clinical tests of the vestibular end-organs, especially the saccule,

it attracted the interest of clinicians and scientists. There had been no other clinical

test of the saccule that was applicable at common clinics. Now much has been

published about VEMP, and many clinicians use this test. VEMP is one of the most

important advances in clinical neurophysiology of the vestibular system.

Prior to the availability of VEMP in its present form [1], other tests had been

proposed, such as using inion responses [2, 3] (Fig. 2), which tried to measure

potentials evoked by sound as a test of the vestibular system. However, tests relying

on these responses were not widely used at clinics. VEMP in its present form,

utilizing biphasic myogenic potentials on the SCM, were first reported in 1992 by

Colebatch and Halmagyi, who reported that VEMP responses on the affected side

disappeared after unilateral vestibular nerve section despite preservation of hearing

[1, 4] (Fig. 3). Colebatch et al. reported in 1994 that VEMP could be recorded in

a patient with bilateral near-total hearing loss [4]. Since that report, clinical and

basic studies concerning VEMP have been further developed. These later studies

clarified that the major vestibular end-organ which responds to sound is the saccule,

and that signals are conveyed via the inferior vestibular nerve [5–11]. Details are

given in the chapters that follow. Here, we want to emphasize that the progress

achieved in this field was brought about by the collaboration of scientists and

clinicians.

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential: Its Basics and Clinical Applications. 3

Toshihisa Murofushi and Kimitaka Kaga

doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-85908-6_1, © Springer 2009](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-9-320.jpg)

![4 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Fig. 2. A typical waveform of inion responses. An active electrode was placed on the nasion and

a reference electrode was on the mastoid. 70dBnHL clicks were presented binaurally; 150

responses were averaged. (From [3], with permission)

10 msec

100 mV

p13

n23

n34

p44

䉱

click

Fig. 1. A typical waveform of vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMP) in a healthy

subject](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-10-320.jpg)

![Introduction 5

Fig. 3. Abolishment of VEMP responses (to 100-dB clicks) following selective vestibular nerve

section on the left. VEMP responses on the left sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) to left ear

stimulation were absent after unilateral vestibular nerve section, although hearing on the left was

preserved. Upper left, recording on the right SCM to left ear stimulation; upper right, recording

on the right SCM to right ear stimulation (presence of responses); asterisk, p13; lower left, record-

ing on the left SCM to left ear stimulation (absence of responses); lower right, recording on the

left SCM to right ear stimulation. (From [4], with permission)

References

1. Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM (1992) Vestibular evoked potentials in human neck muscles

before and after unilateral vestibular deafferentation. Neurology 42:1635–1636

2. Bickford RG, Jacobson JL, Cody DT (1964) Nature of average evoked potentials to sound

and other stimuli in man. Ann NY Acad Sci 112:204–223

3. Cody DT, Jacobson JL, Walker JC, et al (1964) Averaged evoked myogenic and cortical

potentials to sound in man. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 73:763–777

4. Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM, Skuse NF (1994) Myogenic potentials generated by a

click-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57:190–197

5. McCue MP, Guinan JJ Jr (1995) Spontaneous activity and frequency selectivity of

acoustically responsive vestibular afferents in the cat. J Neurophysiol 74:1563–1572

6. McCue MP, Guinan JJ Jr (1997) Sound-evoked activity in primary afferent neurons of a

mammalian vestibular system. Am J Otol 18:355–360

7. Murofushi T, Curthoys IS, Topple AN, et al (1995) Responses of guinea pig primary vestibu-

lar neurons to clicks. Exp Brain Res 103:174–178

8. Murofushi T, Curthoys IS, Gilchrist DP (1996) Response of guinea pig vestibular nucleus

neurons to clicks. Exp Brain Res 111:149–152

9. Murofushi T, Curthoys IS (1997) Physiological and anatomical study of click-sensitive

primary vestibular afferents in the guinea pig. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 117:66–72

10. Murofushi T, Halmagyi GM, Yavor RA, et al (1996) Absent vestibular evoked potentials in

vestibular neurolabyrinthitis: an indicator of involvement of the inferior vestibular nerve?

Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 122:845–848

11. Murofushi T, Matsuzaki M, Mizuno M (1998) Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in

patients with acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124:509–512](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-11-320.jpg)

![Overview of the Vestibular System

Introduction

In this chapter, we review only the fundamental structures associated with the

vestibular system that may be concerned with vestibular evoked myogenic

potentials (VEMPs). Although the cerebellum and cerebrum are also important

for the vestibular system, we do not address them here, as their effects on VEMPs

seem minimal.

Vestibular End-Organs

The human labyrinth consists of the cochlea, otolith organs, and semicircular

canals. The otolith organs and the semicircular canals are vestibular end-organs.

The functions of the vestibular end-organs are basically to monitor the rotational

and linear movement of the head and the orientation of the head to gravity. In

humans, there are two otolith organs (saccule and utricle) and three semicircular

canals (lateral semicircular canal, anterior semicircular canal, and posterior semi-

circular canal) (Figs. 1, 2).

The otolith organs, the saccule and the utricle, sense linear acceleration. The

sensory area of the otolith organ is called the macula. The saccular macula lies on

the medial wall of the vestibule in a spherical recess inferior to the utricular macula.

The saccular macula is hook-shaped and lies predominantly in a vertical position,

whereas the utricular macula is oval and lies predominantly in a horizontal position

(Fig. 3) [1] The plane of the saccular macula is almost orthogonal to that of the

utricular macula (Fig. 4). The surfaces of the maculae are covered by the otolithic

membrane, which contains a superficial calcareous deposit, the otoconia (Fig. 5)

[1–3]. The cilia of the hair cells in the macula protrude into the otolithic membrane.

The otoconia consist of small calcium carbonate crystals [4]. Linear acceleration

including gravity causes deflection of the cilia of the hair cells.

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential: Its Basics and Clinical Applications. 9

Toshihisa Murofushi and Kimitaka Kaga

doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-85908-6_2, © Springer 2009](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-13-320.jpg)

![10 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

The semicircular canals—lateral, anterior, posterior—sense angular accelera-

tion. They are aligned to form a coordinate system [5]. The lateral semicircular

canal makes a 30° angle with the horizontal plane. The other two canals are in

vertical positions almost orthogonal to each other. The sensory area is called the

crista. Hair cells are in the surface of the crista, with their cilia protruding into

the cupula, a gelatinous mass (Fig. 6). Angular acceleration causes deflection of

the cupula, resulting in deflection of the cilia of the hair cells.

Utricle

Saccule

Anterior semicircular canal

Posterior semicircular canal

Lateral semicircular canal Cochlea

Cochlear nerve

Superior vestibular nerve

Inferior vestibular nerve

(a) (b)

(c)

Fig. 1. Inner ear and afferent nerves

Fig. 2. Vestibular end-organs in human temporal bone sections. a Utricular macula. b Saccular

macula. c Crista of the lateral semicircular canal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-14-320.jpg)

![12 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

The macula and crista contain two types of hair cells: type I and type II hair

cells [6] (Fig. 7). The hair cells have stereocilia and a kinocilium on the top. Deflec-

tion of the stereocilia toward the kinocilium causes excitation, whereas deflection

toward the other side causes inhibition. Type I hair cells are shaped like flasks, with

each cell being surrounded by a calyx ending. The type II hair cells, which are like

cylinders, have bouton nerve endings (Figs. 7, 8) [1, 2]. The striola is a distinctive

cupula

hair cell

Fig. 6. Photomicroscopic findings of the guinea pig crista. H&E

kinocilium

stereocilia

excitation

inhibition

calyx type ending

bouton type ending

Type I

Type II

Fig. 7. Two types of hair cell](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-16-320.jpg)

![Overview of the Vestibular System 13

zone running through the center of each macula. The hair cells on each side of the

striola have opposite polarities because their kinocilia point in opposite directions

(Fig. 3). In contrast to the macula, the direction of the polarity of hair cells in one

crista is uniform.

Calyx units are seen in central (striolar) zones. The axon is usually unbranched,

giving rise to a single calyx ending. Bouton units are seen in peripheral (extrastrio-

lar) zones. The axon provides bouton endings to several type II hair cells. Dimor-

phic units innervate all parts of the neuroepithelium. The axon has collateral

branches terminating as calyx endings and bouton endings [6].

Vestibular Nerve

The vestibular nerve contains afferents from the vestibular end-organs and effer-

ents. The cells of afferents are bipolar neurons with their cell bodies in Scarpa’s

ganglion. The vestibular nerve is subdivided into two parts: the superior vestibular

nerve and the inferior vestibular nerve [7] (Fig. 1). The superior vestibular nerve

innervates the cristae of the anterior semicircular canal, the lateral semicircular

canal, the utricular macula, and the anterosuperior part of the saccular macula. The

inferior vestibular nerve innervates the crista of the posterior semicircular canal

and the main part of the saccular macula. Otolith ganglion cells are located ven-

trally in the central portion of the ganglion, whereas canal ganglion cells are located

at the rostral and caudal ends [8, 9].

The vestibular afferent fibers innervating the macula are activated by changes

in the position of the head in space or by linear acceleration, whereas the fibers

innervating the crista are activated by angular acceleration [10–12]. Vestibular

afferents fire spontaneously (65 spikes/s in otolith afferents and 90 spikes/s in canal

afferents) [13, 14]. The baseline firing rates increase in response to excitatory

stimuli and decrease in response to inhibitory stimuli. Based on the regularity of

firing, vestibular afferents are classified into two groups—regularly firing fibers

and irregularly firing fibers [6]—each of which has different features. Irregularly

Bouton type ending

Calyx type ending

Fig. 8. Types of guinea pig primary afferent nerve endings labeled by biocytin. (In collaboration

with Prof. I.S. Curthoys)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-17-320.jpg)

![14 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

firing fibers have thick, medium-sized axons ending as a calyx and dimorphic units.

They have phasic–tonic response dynamics and high sensitivity to head rotation or

linear forces. In contrast, regularly firing fibers have medium-sized, thin axons,

ending as dimorphic and bouton units. They have tonic response dynamics and low

sensitivity to head rotation or linear forces. These differences must be borne in

mind when we consider the sound sensitivity of vestibular afferents.

Vestibular Nucleus

The vestibular nuclei consist of a group of neurons located on the floor of the

fourth ventricle. The main vestibular nuclei are the superior nucleus, lateral

(Deiters’) nucleus, medial nucleus, and inferior (descending or spinal) nucleus (2).

Additionally, there are several small groups of cells. Although primary vestibular

neurons provide multiple branches, which usually innervate secondary vestibular

neurons in all of the four main vestibular nuclei, there are preferences in each

nucleus (8).

The superior vestibular nucleus contains medium-sized neurons with some mul-

tipolar cells. The superior vestibular nucleus receives strong projections from

semicircular canals. The medial vestibular nucleus consists of cells of many sizes

and shapes that are close together. The upper part of the medial vestibular nucleus

receives fibers from the semicircular canals and the fastigial nucleus and flocculus

of the cerebellum. Saccular and utricular afferents project to the middle part of

the nucleus. The caudal part of the nucleus receives fibers from the cerebellum.

The lateral vestibular nucleus contains giant cells. The dorsocaudal portion

receives afferents from the cerebellum, whereas the rostrovertebral portion receives

primary vestibular afferents. The inferior vestibular nucleus consists of small and

medium-sized cells with occasional giant cells. The rostral part of the inferior

vestibular nucleus receives strong projections from the otolith organs and the

semicircular canals.

Summarized from the standpoint of primary otolith afferents, saccular afferents

terminate mainly in the rostral part of the inferior vestibular nucleus and the ros-

troventral portion of the lateral nucleus; and utricular afferents terminate mainly in

the rostral portion of the inferior vestibular nucleus, and the medial vestibular

nucleus [8, 9, 15].

On the basis of neurophysiological studies, two types of secondary vestibular

neuron were identified [16]. Ipsilateral rotation of the head causes type I neurons

to be excited and type II neurons to be inhibited. Type I neurons are monosy-

naptically activated by ipsilateral primary afferents, whereas type II neurons

receive inputs via commissural connections either from neurons in the reticular

substance or directly from contralateral type I neurons [2]. Contralateral labyrinth

stimulation excites type II neurons, resulting in inhibition of type I neurons

(Fig. 9).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-18-320.jpg)

![Overview of the Vestibular System 15

Vestibulospinal Reflex

The vestibulospinal reflex (VSR) serves to stabilize the head and controls erect

stance relative to gravity under both static and dynamic conditions [17]. Stimula-

tion of the vestibular end-organs leads to various patterns of activation of neck

and body muscles. Activation of the neck muscles is described later as the vestibu-

locollic reflex.

The VSR prevents falling and maintains the body’s position. There are three

major pathways: the lateral vestibulospinal tract (LVST); the medial vestibulospinal

tract (MVST); and the reticulospinal tract (RST) [18] (Fig. 10). The LVST origi-

nates in the lateral nucleus and descends in the ipsilateral ventral funiculus of the

spinal cord. The MVST originates in the medial, inferior, and lateral nuclei and

descends in the medial longitudinal fasciculus bilaterally as far as the mid-thoracic

level [17, 19]. Linear and angular head acceleration causes increased muscle tones

in the ipsilateral extensor muscles and decreased muscle tones in the ipsilateral

flexor muscles via the LVST [17, 20].

Vestibulocollic Reflex

The vestibulocollic reflex (VCR) operates to stabilize the head in space by neck

movements. The MVST and LVST provide direct connections to neck motoneurons

as well as indirect connections. Connections between vestibular end-organs and

Fig. 9. Interrelation of types I and II secondary vestibular neurons. Light neurons are excitatory;

dark neurons are inhibitory

Type I

Type II

Type II

Type I

Lateral

semiciicular canal

Vestibular nerve

Vestibular nucleus

midline](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-19-320.jpg)

![Overview of the Vestibular System 17

neck motoneurons are summarized in Table 1 [21]. Neck muscles are classified

into three types: extensors, flexors, rotators. The sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM)

is classified as a rotator type. Concerning VEMPs, it should be noted that moto-

neurons of the SCM have disynaptic inhibitory inputs from the ipsilateral saccule

with no projections from the contralateral saccule [22] (Table 1, Fig. 11).

Vestibuloocular Reflex

The vestibuloocular reflex (VOR) maintains gaze during head and body movements

[23]. This gaze stability is achieved by activation of vestibular end-organs, includ-

ing activation of semicircular canals to angular acceleration and of otolith organs

to linear translation and gravity. In other words, the VOR produces extraocular

muscle contraction to compensate for a specific head movement, thereby maintain-

ing gaze stability. The connections of the semicircular canals with extraocular

muscles are summarized in Table 2.

The eye movements induced by the stimulation of the otolith organs and the

pathways from the otolith organs to extraocular muscles are less clearly defined

than those from the semicircular canals and are somewhat controversial. According

to Suzuki et al. [24], electrical stimulation of the utricular nerve in spinalized, alert

cats mainly produced contraversive torsional eye movement with simultaneous

upward shift in ipsilateral eyes, downward shift in contralateral eyes, and slight

Fig. 11. Sacculosternocleidomastoid (SCM) and utriculosternocleidomastoid pathways Filled

circles, inhibitory neurons; open circles, excitatory neurons. (from Fig. 4 of ref. 22, Springer, with

permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-21-320.jpg)

![18 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

contralateral horizontal shift of both eyes. Curthoys reported that electrical stimula-

tion of the utricular macula in guinea pigs produced upward or upward-torsional

eye movements [25]. Fluur and Mellstrom reported that electrical stimulation of

the utricular macula in alert cats produced eye movements whose direction depended

on the location of the stimulating electrode [26]. Concerning horizontal eye

movement, Goto et al. [27] confirmed that utricular nerve stimulation in cats

evoked horizontal eye movements to the stimulated side, supporting prior findings

of projection of the utricular nerve to the ipsilateral abducens nucleus [28, 29].

Eye movement due to saccular stimulation is more obscure than that due to

utricular stimulation. The saccule contributes more weakly to eye movements than

the semicircular canals or the utricule [30]. Previous studies suggested that the main

eye movement induced by saccular stimulation could be vertical [25, 31, 32].

References

1. Schuknecht HF (1993) Pathology of the ear. 2nd edn. Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia

2. Baloh RW, Honrubia V (1990) Clinical neurophysiology of the vestibular system. 2nd edn.

Davis, Philadelphia

3. Lim DJ (1973) Ultrastructure of the otolithic membrane and the cupula. Adv Otorhinolaryn-

gol 19:35–49

4. De Vries H (1951) The mechanics of the labyrinth otoliths. Acta Otolaryngol 38:262–273

5. Blanks RHJ, Curthoys IS, Markham CH (1975) Planar relationships of the semicircular canals

in man. Acta Otolaryngol 80:185–196

6. Goldberg JF, Lysakowski A, Fernandez C (1992) Structure and function of vestibular nerve

fibers in the chinchilla and squirrel monkey. Ann NY Acad Sci 656:92–107

7. Lorente De No R (1933) Anatomy of the eighth nerve: the central projection of the nerve

endings of the internal ear. Laryngoscope 43:1–38

8. Gacek RR (1969) The course and central termination of first order neurons supplying

vestibular end organs in the cat. Acta Otolaryngol 254:1–66

9. Gacek RR (2008) A place principle for vertigo. Auris Nasus Larynx 35:1–10

10. Fernandez C, Goldberg JM (1971) Physiology of peripheral neurons innervating semicircular

canals of the squirrel monkey. II. Response to sinusoidal stimulation and dynamics of periph-

eral vestibular system. J Neurophysiol 34:61–675

Table 2. Connection pattern to motoneurons of extra-ocular

muscles from afferents of the semicircular canals

Semicircular canal Excitation Inhibition

Anterior I-SR I-IR

C-IO C-SO

Posterior I-SO I-IO

C-IR C-SR

Lateral I-MR C-MR

C-LR I-LR

(from ref. 21)

I, ipsilateral; C, contralateral; MR, mdial rectus;

LR, lateral rectus; SO, superior oblique; IR, inferior rectus;

IO, inferior oblique; SR, superior rectus](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-22-320.jpg)

![Sound Sensitivity of the Vestibular

End-Organs and Sound-Evoked

Vestibulocollic Reflexes in Mammals

Sound Sensitivity of the Vestibular System

Tullio first reported that surgical fenestration of the bony labyrinth in avians and

mammals made the labyrinth sound-sensitive [1–3]. This phenomenon—sound

sensitivity of the vestibular system—has been known as the Tullio phenomenon

[3, 4]. Bekesy reported head movements in response to relatively loud sounds [3, 5]

and suggested that this effect might be caused by stimulation of the otolith organs.

Later, Young et al. reported that primary vestibular afferents of squirrel monkeys

could respond to sound and vibration, although the number of examined vestibular

neurons was limited and the methods of threshold determination (a phase-locking

threshold) were not familiar [6]. According to their study, all the vestibular end-

organs (three canals and two maculae) responded to sound. Among the five end-

organs, the saccular macula showed the lowest thresholds. The best frequencies did

not exceed 1000 Hz to sound and 500 Hz to vibration. Cazals et al. created guinea

pigs with selective cochlear loss and preserved the vestibular system using amika-

sin, an aminoglycoside. These animals displayed evoked potentials to sound,

although their cochlea was completely destroyed [7, 8]. Recording evoked poten-

tials on the eighth nerve revealed that the responses were prominent on the inferior

vestibular nerve [9]. These studies suggested that the vestibular end-organs could

respond to loud sounds and that the saccule might be the most sound-sensitive

among the vestibular end-organs.

During the 1990s, several articles concerning sound sensitivity of vestibular

neurons were published. McCue and Guinan reported that saccular afferents of cats

responded to intense sound. In their study, the best frequency of saccular afferents

to air-conducted sound was around 500 Hz (Fig. 1) [10–12]. Murofushi et al.

showed that primary vestibular afferents of guinea pigs could respond to intense

air-conducted clicks (Fig. 2) [13, 14]. These neurons were mainly in the inferior

vestibular nerve and could also respond to static tilts. None of the angular accelera-

tion-sensitive neurons—canal neurons—responded to clicks. These findings sug-

gested that the saccular afferents could be sensitive to air-conducted sound. Most

of these click-sensitive neurons showed irregular spontaneous firing. Irregularly

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential: Its Basics and Clinical Applications. 20

Toshihisa Murofushi and Kimitaka Kaga

doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-85908-6_3, © Springer 2009](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-24-320.jpg)

![Sound Sensitivity and Sound-Evoked Vestibulocollic Reflexes 21

firing fibers have thick, medium-sized axons ending as calyx and dimorphic units

[15]. Hence, type I hair cells on the saccular macula are sound (click)-sensitive

among the vestibular end-organs. Murofushi et al. also reported that vestibular

nucleus neurons in the lateral vestibular nucleus and in the rostral portion of the

inferior vestibular nucleus are sound (click)-sensitive (Fig. 3) [16]. Although these

findings imply that saccular afferents could respond to air-conducted sound, they

do not exclude the possibility that utricular afferents might respond to air-con-

ducted sound as well, especially to relatively low-frequency sound.

In the vestibular end-organs, response patterns to bone-conducted sound (vibra-

tion) are different from the patterns seen with air-conducted sound. Hair cells in

Fig. 1. Tuning curves of sound-sensitive vestibular afferents of cats. SPL, sound pressure level.

(from Fig. 6 of ref. 11, American Physiological Society, with permission)

Fig. 2. Responses of guinea pig primary vestibular neurons to clicks—70 dB above the auditory

brainstem response (ABR) threshold. (from Fig. 1 of ref. 14, Taylor & Francis, with permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-25-320.jpg)

![22 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

the utricular macula and the saccular macula respond to bone-conducted sound.

According to Curthoys et al., most of the irregular otolithic afferents studied

(82.8%) showed a clear increase in the firing rate in response to bone-conducted

sound [17]. In their study, bone-conducted sound-sensitive afferents could be of

utricular origin because many of the bone-conducted sound-sensitive afferents were

in the superior vestibular nerve, and they were sensitive to roll tilts. These authors

also reported that regular otolithic afferents were less sensitive to bone-conducted

sound, and only a few canal afferents responded to it. These findings suggested

that vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) to bone-conducted sound

[18, 19] might be produced by vestibular end-organs from a different population

than the VEMPs to air-conducted sound.

Neural Pathway of the Sound-Evoked Vestibulocollic Reflex

Among the vestibular end-organs in mammals, the saccular macula seems to

respond especially well to air-conducted sound; and among the hair cells on the

saccular macula, the type I hair cells around the striola seem to be the most sensi-

tive. What then is the neural pathway of the sound-evoked vestibulocollic reflex?

Primary afferents of the saccule are mainly in the inferior vestibular nerve.

Therefore, inputs to the vestibular system of sound stimulation are mostly trans-

mitted via the inferior vestibular nerve. According to Kushiro et al. [20], saccular

Fig. 3. Recording sites of click-sensitive vestibular nucleus neurons of guinea pigs. LV, lateral

vestibular nucleus; DV, descending vestibular nucleus; MV, medial vestibular nucleus; SV, supe-

rior vestibular nucleus; icp, inferior cerebellar peduncle; CN, cochlear nucleus; as, acoustic stria;

n7, facial nerve; g7, genu nervi facialis; N6, abducens nucleus. a is the most rostral and c is the

most caudal. (from Fig. 2 of ref. 16, Springer, with permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-26-320.jpg)

![Sound Sensitivity and Sound-Evoked Vestibulocollic Reflexes 23

afferents in cats have inhibitory projection to the ipsilateral motoneurons of the

sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) and no contralateral projection. These authors

also showed that this projection was transmitted via the medial vestibulospinal

tract. Based on these findings, the neural pathway of the air-conducted sound-

evoked vestibulocollic reflex recorded on the SCM is thought to be as shown in

Fig. 4. The VEMPs are clearly ipsilateral-dominant (described later). Therefore,

the supposed neural pathway corresponds well with the results of VEMP studies

in humans.

Provided that bone-conducted sound simulates the utricular macula as well as

the saccular macula, VEMPs to bone-conducted sound might have some features

different from those of VEMPs to air-conducted sound. Utricular afferents are

located in the superior vestibular nerve. Utricular afferents have not only inhibitory

projection to the ipsilateral motoneurons of the SCM but also excitatory projection

to the contralateral motoneurons of the SCM [20]. When one uses bone-conducted

sound as the stimulus, one should bear in mind that the neural pathway of VEMPs

for bone-conducted sound might be different from the pathway of VEMPs for air-

conducted sound.

When sound is presented to the ear, one may concern the coexistence of a

“sound-evoked cochleocollic reflex”. However, direct projection from the cochlear

nucleus to the motoneurons of the SCM is not known. Therefore, the sound-evoked

cochleocollic reflex, if any, would be transmitted via the reticular formation, taking

longer latencies than the sound-evoked vestibulocollic reflex. Furthermore, it would

be evoked bilaterally. Some of the later components of VEMPs (n34–p44) [21]

may be a sound-evoked cochleocollic reflex.

Fig. 4. Pathway of air-conducted sound-evoked vestibulocollic (otolith-sternocleidomastoid)

reflex. SCM, sternocleidomastoid muscle

inferior vestibular nerve

medial vestibulospinal tract

accessory nerve

ipsilatral SCM

saccule](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-27-320.jpg)

![Recording and Assessing VEMPs

Suitable Subjects for Recording VEMPs

Basically, vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) testing is applicable to

all subjects who require evaluation of vestibular functions. However, it is difficult

to obtain responses from subjects who are not cooperative during the testing and

who for some reason cannot contract the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) during

the recording (e.g., a comatose patient). In subjects with air–bone gaps in pure-tone

audiometry, special care is required because responses are abolished or decreased

owing to conductive hearing loss [1, 2].

Methods of Recording VEMPs

We usually use surface electrodes to record VEMPs, placing active electrodes sym-

metrically on the middle third of the SCM and indifferent electrodes on the lateral

end of the upper sternum (Fig. 1) [3]. When the active electrodes are too close to

the indifferent electrodes, the amplitudes of the responses are decreased [4]; and

when they are too close to the mastoid, responses are contaminated by postauricular

responses [5]. The ground electrode is placed on the nasion or the chin.

Acoustic stimuli usually comprise clicks (0.1 ms) or short tone bursts (STBs)

(500 Hz, rise/fall time 1 ms, plateau time 2 ms). We first present 95-dBnHL

(decibels, normal hearing level) clicks or STBs and attenuate the intensity when

we want to determine the threshold of the responses. STBs of 500 Hz evoke larger,

clearer VEMP responses than clicks [6]. However, investigators should note that

STBs of 500 Hz might evoke utricular hair cells as well as saccular hair cells,

whereas clicks selectively evoke saccular hair cells [7, 8]. The repetition rate of

stimulation is usually 5 Hz. When the repetition rate is increased, the amplitude of

the responses may be decreased. This tendency becomes clear when the repetition

rate is more than 20 Hz [9]. On the other hand, subjects may become tired when

the repetition rate is decreased because the lower repetition rate requires contraction

of the SCM for longer periods. Thus, 5 Hz is the optimal repetition rate.

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential: Its Basics and Clinical Applications. 25

Toshihisa Murofushi and Kimitaka Kaga

doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-85908-6_4, © Springer 2009](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-29-320.jpg)

![26 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Electromyographic (EMG) activities are amplified and bandpass-filtered (20–

2000 Hz). The time window for analysis is 50–100 ms. Responses to 100–200

stimuli (click VEMPs) are averaged. It is important to maintain the contraction

of the SCM during recording. VEMP amplitudes show strong correlations to

background muscle activity (Fig. 2). Responses cannot be observed without muscle

contraction.

As VEMP amplitudes show strong correlations with the extent of muscle con-

traction, efforts to minimize the effects of muscle contraction fluctuation may be

required. To minimize such effects, it is proposed that 1) VEMP amplitudes be

corrected based on the extent of muscle contraction and 2) the muscle contraction

be maintained at a constant level using feedback methods. To correct VEMP ampli-

tudes, we use an average of rectified background muscle activity during a prestimu-

lus period of 20 ms [10] (Fig. 3). The corrected amplitude (CA) of VEMP is defined

as a ratio.

CA = (raw amplitude of p13–n23)/(mean background amplitude)

Fig. 1. Electrode placement for vestibular

evoked myogenic potential (VEMP)

recording

Fig. 2. Correlation between the VEMP

amplitude to 95-dBnHLtone bursts (500 Hz)

and mean background muscle activity in

healthy subjects. The correlation coefficient

was 0.83. dBnHL, dB normal hearing level;

0 dBnHL, average subjective threshold of

sound perception in healthy subjects. (from

Fig. 2 of ref. 24, Elsevier, with permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-30-320.jpg)

![Recording and Assessing VEMPs 27

For this purpose, one must average the rectified EMG during a prestimulus period.

A feedback method using a blood pressure manometer has been proposed to main-

tain the muscle contraction constant during VEMP recording [11].

To contract the SCM, we usually ask subjects in the supine position to raise

their head from the pillow. Alternatively, rotating the neck (in the supine position

or upright) or having the examiner push the patient’s forehead can be useful

(Fig. 4). The rotation method may be easier. However, investigators should note

that only unilateral responses are recordable, and muscle contraction becomes

easily asymmetrical when this method is applied. Head position itself does not

affect VEMP responses [12]. According to Isaacson et al., when the amplitude was

corrected according to tonic EMG activity, no significant difference was noted

among various test positions [13].

Fig. 3. Correction of amplitudes using rectified electromyography (EMG). Upper trace, unrecti-

fied response; lower trace, rectified response. Background muscle activities were calculated using

the shaded areas. VEMP amplitudes were corrected based on background muscle activity. (from

Fig. 1 of ref. 12, Taylor & Francis, with permission)

Fig. 4. Methods to contract the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). a Position supine with the

head raised, b position sitting with the head turned away from the tested ear, c position sitting

with the head pushed against the finger to provide resistance](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-31-320.jpg)

![28 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Normal VEMP Responses

In healthy subjects, VEMP responses consist of initial positivity followed by nega-

tivity with short latencies. This biphasic response is termed p13–n23 after the peak

latency. In our clinic, the means ± SD of p13 and n23 were 11.8 ± 0.86 ms and

20.8 ± 2.2 ms, respectively (95-dBnHL clicks) [14]. Responses to STBs have 2- to

3-ms longer peak latencies [6]. These responses are clearly ipsilateral-dominant.

In other words, p13–n23 can be recorded on the SCM ipsilateral to the stimulated

ear, although p13–n23 on the contralateral side is absent or small (Fig. 5) [15].

Following p13–n23, later components (n34–p44) can be also observed (Fig. 6) [16].

Fig. 5. Laterality of VEMP responses.

VEMP responses (p13–n23) to 95-dBnHL

clicks were clearly ipsilateral-dominant.

(from Fig. 1 of ref. 15, Taylor & Francis,

with permission)

10 msec

100 m V

p13

n23

n34

p44

Fig. 6. Typical VEMP waveform in response to 95-dBnHL clicks in a healthy subject. Responses

are on the ipsilateral SCM to the stimulated ear](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-32-320.jpg)

![Recording and Assessing VEMPs 29

Later components are not of vestibular origin [1]. Amplitudes of responses

(p13–n23) depend on the degree of muscle contraction. In the ordinary situation,

the amplitudes range from 50 to 200 μV.

The polarity of the initial responses (positivity followed by negativity) implies

that this myogenic potential is caused by inhibitory inputs to the SCM [17]. This

finding is consistent with neurophysiological data from cats [18].

Parameters for Assessing VEMPs

The following parameters are used for clinical evaluation. In this section, VEMPs

refer to the early component (p13–n23).

Presence of VEMPs

VEMPs are usually present in healthy subjects, whereas some elderly subjects

exhibit an absence of response. This absence is considered pathological in subjects

<60 years of age (Fig. 7). In other words, absence of responses suggests dysfunc-

tion of the sacculocollic pathway. Even in older subjects, the unilateral absence of

responses is pathological. If an absence of VEMP responses is observed, an exam-

iner should first confirm that the headphone was adequately placed on the head.

Second, the examiner should determine if the subject has conductive hearing loss.

The absence of responses in patients with conductive hearing loss does not mean

dysfunction of the saccule or its afferents.

Fig. 7. Example of unilateral absence

of VEMP responses on the left side (L).

R, right side](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-33-320.jpg)

![30 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Interaural Difference of VEMP Amplitude

Side-to-side differences of VEMP amplitude can be expressed as percent VEMP

asymmetry [3].

%VEMP asymmetry = 100 |Ar − Al|/(Ar + Al)

where Ar and Al are the amplitudes of p13–n23 on the right and on the left; and

|Ar − Al| is the absolute value of Ar − Al.

When the affected side is already known, the percent VEMP asymmetry should

be calculated as follows.

%VEMP asymmetry = 100 (Au − Aa)/(Au + Aa)

where Au is the amplitude of p13–n23 on the unaffected side; and Aa is the ampli-

tude of p13–n23 on the affected side.

In our institution, we set the upper limit of percent VEMP asymmetry as 34.1

(mean +2 SD) in healthy subjects. When the percent VEMP asymmetry exceeds

34.1, the asymmetry is pathological. We usually regard the decreased side as

pathological unless there are other specific reasons for the abnormal result (Fig. 8).

Although a similar normal range was reported from another laboratory [19], the

normal limit should be set at each institution because recording conditions cannot

be totally identical.

Peak latency

Significant delay of peak latencies is also pathological. As the peak latency of p13

shows better reproducibility than that of n23, the peak latency of p13 is more

available clinically. Prolonged latencies are signs of retrolabyrinthine or central

Fig. 8. Example of unilaterally decreased

amplitudes on the left side](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-34-320.jpg)

![disorders (Fig. 9) [14, 20, 21]. In our institution, the means ± SD of p13 and n23

to 95 dBnHL click were 11.8 ± 0.86 ms and 20.8 ± 2.2 ms, respectively. The normal

range for peak latency should be established at each institution.

Threshold

In comparison with the auditory brainstem response (ABR), which is an evoked

potential of cochlear origin, the VEMP threshold is much higher. In our clinic, the

VEMP thresholds in healthy subjects (clicks) were ≥85 dBnHL. According to

Colebatch et al. [22], the mean threshold of VEMP responses to clicks in healthy

subjects was 86 dBnHL and the lowest was 70 dBnHL. When the threshold to click

stimulation is lower than 70 dBnHL, it is definitely pathological, suggesting hyper-

sensitivity of vestibular end-organs to sound (the Tullio phenomenon) (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9. Example of prolonged latencies

(both sides). (from Figure of ref. 20, BMJ

Publishing Group, with permission)

Fig. 10. Example of low VEMP thresh-

olds. In this subject, the threshold was

70 dBnHL

Recording and Assessing VEMPs 31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-35-320.jpg)

![32 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Miscellaneous

In addition to the above-mentioned major parameters, some others can be applied.

Frequency Tuning Characteristics

Rauch et al. reported that patients with Meniere’s disease showed less tuning at

500 Hz and threshold elevation, whereas healthy subjects showed the best responses

at 500 Hz [23]. Their results suggested that a new parameter concerning frequency

tuning characteristics might be applicable for VEMP assessment. For example, the

ratio of corrected VEMP amplitude at 500 Hz to that at 1000 Hz or the ratio of the

threshold at 500 Hz to that at 1000 Hz might be applied.

Acoustic/Galvanic Ratio

The characteristics of the responses to acoustic stimuli and galvanic stimuli might

be compared. Because galvanic stimulation bypasses the labyrinth and stimulates

the vestibular nerve directly, labyrinthine damage does not affect galvanic VEMPs

whereas it does affect acoustic VEMPs. Therefore, the acoustic VEMP amplitude/

galvanic VEMP amplitude ratio can be a useful indicator for differentiating laby-

rinthine from retrolabyrinthine disorders [24–26]. This issue is discussed in the

chapter “VEMP Variants.”

References

1. Welgampola MS, Colebatch JG (2005) Characteristics and clinical applications of vestibular-

evoked myogenic potentials. Neurology 64:1682–1688

2. Bath AP, Harris N, McEwan J (1999) Effect of conductive hearing loss on the vestibulocollic

reflex. Clin Otolaryngol 24:181–183

3. Murofushi T, Matsuzaki M, Mizuno (1998) Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in patients

with acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 124:509–512

4. Sheykholeslami K, Murofushi T, Kaga K (2001) The effect of sternocleidomastoid electrode

location on VEMP. Auris Nasus Larynx 28:41–43

5. Endoh T, Hojoh K, Sohma H, et al (1987) Auditory postauricular responses in patients with

peripheral facial nerve palsy. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 446:76–80

6. Murofushi T, Matsuzaki M, Wu CH (1999) Short tone burst-evoked myogenic potentials on

the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 125:660–664

7. Murofushi T, Curthoys IS, Topple AN, et al (1995) Responses of guinea pig primary vestibu-

lar neurons to clicks. Exp Brain Res 103:174–178

8. Murofushi T, Curthoys IS (1997) Physiological and anatomical study of click-sensitive

primary vestibular afferents in the guinea pig. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 117:66–72

9. Wu CH, Murofushi T (1999) The effect of click repetition rate on vestibular evoked myogenic

potential. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 119:29–32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-36-320.jpg)

![VEMP Variants

Introduction

Originally, vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) were recorded on

cervical muscles, especially the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM), in regard

to air-conducted sound [1, 2]. However, there were some limitations of this test.

To overcome these limitations, variants of VEMP analysis have been proposed and

are classified into two categories: variants stimulation methods and recording

methods.

Variants of Stimulation Methods

In addition to conventional unilateral air-conducted sound stimulation, a binaural

simultaneous air-conducted sound stimulation method, a tapping method, a bone-

conducted sound method, and a galvanic stimulation method have been reported.

Binaural Simultaneous Stimulation Method

The binaural simultaneous air-conducted sound stimulation method was proposed

to reduce physical loading of subjects. During VEMP recording, subjects must keep

contracting the SCM, and it is sometimes difficult for elderly subjects to maintain

the contraction.

The saccular projection to the SCM is unilateral [3]. In other words, acoustic

stimulation to one ear affects only the SCM ipsilateral to the stimulated ear. In

healthy subjects, VEMPs are clearly ipsilateral-dominant [4]. Therefore, simultane-

ous binaural stimulation seems to enable sacculocollic reflexes on both sides at the

same time. Murofushi et al. compared VEMP responses of monaural click stimula-

tion with responses to binaural click stimulation in patients with unilateral peri-

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential: Its Basics and Clinical Applications. 34

Toshihisa Murofushi and Kimitaka Kaga

doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-85908-6_5, © Springer 2009](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-38-320.jpg)

![VEMP Variants 35

pheral vestibular dysfunction [5]. In 26 of the 28 patients, results for monaural

stimulation coincided with those for binaural stimulation (Fig.1, Table 1). Among

the two patients without coincidence, one patient showed bilateral normal responses

to monaural stimulation despite decreased responses on one side to binaural simul-

taneous stimulation, and the other patient showed a unilateral absence to monaural

stimulation despite the bilateral absence of responses to binaural stimulation. The

reasons for the discordance were not clear. However, the high rate of coincidence

and no false-negative results encouraged us to apply the binaural simultaneous

stimulation method as a clinical screening test.

Tapping and Bone-Conducted Sound Method

Conduction problems in the external ear or middle ear attenuate the intensity of

air-conducted sound. Therefore, subjects with conductive hearing loss may show

an absence of response despite a normal sacculocollic pathway. The tapping and

bone-conducted sound method was primarily applied to measure vestibulocollic

Monaural stimulation

Binaural stimulation

Fig. 1. Vestibular evoked myogenic

potential (VEMP) responses to monau-

ral individual stimulation and binaural

simultaneous stimulation in a woman

with a left acoustic neuroma. The patient

showed absent responses on the left

sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) to

left ear stimulation and to binaural

stimulation. L, left side; R, right side.

(from Fig. 1 of ref. 5, Springer, with

permission)

Table 1. Results to unilateral stimulation and bilateral stimulation. (from Table 1 of ref. 5,

Springer, with permission)

Bilateral stimulation

Unilateral stimulation

Bilaterally

normal

Unilaterally

decreased

Unilaterally

absent

Bilaterally

absent Total

Bilaterally normal 9 0 0 0 9

Unilaterally decreased 1 0 0 0 1

Unilaterally absent 0 0 15 0 15

Bilaterally absent 0 0 1 2 3

Total 10 0 16 2 28](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-39-320.jpg)

![36 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

reflexes in patients with conducted-hearing loss, as these stimulations are thought

to bypass the middle ear and act directly on the inner ear (Fig. 2).

The tapping method applied vibratory stimulation to the subjects’skulls. Tapping

with a tendon hammer evokes biphasic myogenic responses on the SCM as evoked

by air-conducted sound (Figs. 3, 4) [6–8]. The tapping site is the forehead (Fz) or

mastoid. Recording conditions are basically the same as for VEMP responses to

Air-conducted

sound

Bone-

conducted

sound,

tapping

Galvanic

stimuli

Fig. 2. Stimulation methods and supposed stimulated sites

Fig. 3. Tendon hammer that can send trigger signals to the averager](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-40-320.jpg)

![VEMP Variants 37

air-conducted sound. In a study of patients without conductive hearing loss, so long

as we concerned only if the results were normal 14 of 15 patients showed the same

results with the tapping method as were seen with the air-conducted click method.

However, many of them showed delayed positivity (Table 2). Although we had

regarded the delayed positivity as delayed p13, the positivity might be an inverted

response preceded by negativity (n13) (Fig. 5). There was no clear relation between

the responses evoked by tapping and pure-tone hearing. These findings suggested

that myogenic potentials evoked by tapping should be of vestibular origin but that

parts other than the saccule could be also stimulated. Brantberg and Mathiesen

reported that tapping-evoked myogenic potentials were preserved after resection

of the inferior vestibular nerve [9]. Their findings supported our assumption.

As described above, the tapping method is a good alternative to the conventional

VEMP procedure. One problem with the tapping method, though, was the difficulty

of calibrating the stimulation. The bone-conducted sound method overcomes

this defect. For recording VEMPs to bone-conducted sound, a bone vibrator—an

apparatus to measure pure-tone hearing thresholds—was first applied [10–14].

Currently, a bone vibrator with stronger intensity is available [15]. The bone

Fig. 4. VEMPs to 95-dBnHL clicks and myogenic responses to tapping in a healthy subject

Table 2. Results of myogenic potentials to clicks and tapping

Parameter Normal

Abnormal

Total

Decreased Absent Delayed

Normal 3 0 0 0 3

Abnormal

Decreased 1 0 0 1 2

Absent 0 0 4 5 9

Delayed 0 0 0 1 1

Total 4 0 4 7 15](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-41-320.jpg)

![38 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

vibrator is placed on the mastoid or forehead. The other recording conditions

are basically the same as those for air-conducted sound. The optimal frequencies

for VEMPs to bone-conducted sound ranged from 200 to 250 Hz [14, 16]. As for

the tapping method, bone-conducted sound can stimulate not only the saccule but

other parts of the vestibular end-organs as well. A neurophysiological experiment

with guinea pigs suggested that the utricle could also be stimulated by bone-

conducted sound [17].

These methods—the tapping method and the bone-conducted sound method—

are suitable for assessing vestibular function of subjects with conductive hearing

loss [11–13]. One should note that these methods stimulate vestibular end-organs

on both sides. Whereas the saccular projection to the SCM is uncrossed, the utricu-

lar projection to the SCM is not only uncrossed but also crossed. Utricular stimula-

tion could have excitatory inputs to the contralateral SCM [3]. Therefore, we should

take the crossed pathway into account when assessing the results.

Galvanic Stimulation

Galvanic stimulation has been used for a galvanic body sway test and a galvanic

eye movement test [18–21]. Galvanic stimulation has been thought to bypass the

labyrinth and act directly on the vestibular nerve (Fig. 2) and thus is useful for

differentiating retrolabyrinthine lesions from labyrinthine lesions. Short-duration

galvanic stimulation has been also applied to patients with vestibular disorders for

this purpose [20–22]. That these potentials are of vestibular origin was confirmed

by the disappearance of myogenic potentials on the SCM after vestibular nerve

section [23].

Fig. 5. VEMP (95-dBnHL clicks) and myogenic responses to tapping in a woman with a left

acoustic neuroma. She showed absent responses to clicks and delayed responses to tapping.

Inverted responses?, small negativity might be an inverted response](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-42-320.jpg)

![VEMP Variants 39

The recording methods of myogenic potentials to galvanic stimuli are as follows.

The electrodes for stimulation were placed on the forehead (anode) and mastoid

(cathode), or on bilateral mastoids. The cathodal electrode should be placed on

the mastoid that an examiner wants to stimulate. The procedure is contraindicated

in patients who have an implanted electrical device such as a pacemaker or

a cochlear implant. It should also not be applied to patients who have medical

history of epilepsy.

A current of 3–4 mA (duration 1–2 ms) is used as the galvanic stimulus. Band-

pass filters, stimulation rate, and time window for analysis are the same as for

acquiring VEMPs to acoustic stimuli. Responses to 50–100 stimuli are averaged.

Galvanic stimulation produces huge electrical artifacts. To remove these artifacts,

the responses obtained without SCM contraction are subtracted from the responses

with SCM contraction [21, 22]. Using this subtraction method, we can get biphasic

(positive–negative) responses similar to VEMPs to acoustic stimuli (Fig. 6). We

call the first positivity p13g and the following negativity n23g. The means ± SD

of p13g and n23g with our method (3 mA, 1 ms) [21] were 11.4 ± 1.3 ms and 19.0

± 2.1 ms, respectively. The mean threshold was 2.5 mA. As these myogenic

potentials were abolished by vestibular nerve section [22], we call these myogenic

potentials to short-duration galvanic stimuli “galvanic VEMPs.”

As expected, patients with labyrinthine lesions such as Meniere’s disease have

normal galvanic VEMPs even though they had an absence of click VEMPs on

the affected side. In contrast, patients with retrolabyrinthine lesions (e.g., acoustic

neuroma) showed a tendency toward abnormal galvanic VEMPs in addition to

absent VEMPs in response to clicks [21]. This combined method of acoustic

p13g

n23g 10 msec

200 m V

100 m V

10 msec

With muscle contraction

Without muscle contraction

(a)

(b)

Fig. 6. Subtraction methods to make responses clearer. (from Fig. 1 of ref. 21, Elsevier, with

permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-43-320.jpg)

![40 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

VEMPs and galvanic VEMPs has been applied for lesion site studies of various

diseases, as described in the clinical application chapters later in this book

[21, 24–27].

At an early stage, this combined method was applied only to patients with absent

VEMPs to acoustic stimuli. Recently, this combined method has been applied to

patients with preserved acoustic VEMPs. We can calculate the ratio of corrected

p13–n23 amplitudes to tone burst stimuli/corrected p13g–n23g amplitudes to gal-

vanic stimuli (the TG ratio). The TG ratio is significantly smaller on the affected

side of patients with endolymphatic hydrops (a representative inner ear disease)

than it is in healthy subjects or on the unaffected side of patients [28]. This change

in the TG ratio was not observed in patients with an acoustic neuroma. The

combined method of acoustic and galvanic VEMPs for lesion site studies is also

applicable to subjects with preserved acoustic VEMPs.

Variants of Recording Methods

Vestibular Evoked Extraocular Potential

Recently, myogenic potentials to acoustic stimuli recorded around the eyes—

vestibular evoked extraocular potential (oVEMP)—have been reported [15, 29, 30].

These responses consist of several peaks. The first peak is a negative deflection

with short tone bursts (mean 10.5 ms to 135-dBSPL, 500-Hz air-conducted bursts)

followed by a positive deflection (mean 15.9 ms) [30]. When air-conducted sounds

were presented, responses were contralateral eye-dominant and clearly recorded on

the electrodes placed underneath the lower eyelid [30] (Fig. 7, Table 3).

With our recording method [30], active electrodes are placed on the face

just inferior to each eye, with reference electrodes placed 1–2 cm below. Electro-

myography (EMG) signals are amplified and bandpass-filtered between 5 and

500 Hz. The time window for analysis is 50 ms. Although we prefer air-conducted

sound (500-Hz short tone burst, up to 135 dBSPL) because of unilateral stimula-

tion, others prefer bone-conducted sound or tapping because of clearer responses

[15, 29, 30]. Responses to 100 stimuli are averaged. Subjects are instructed to

maintain an upward gaze during recording because responses are the largest at this

gaze position.

It is believed that these responses reflect the vestibuloocular reflex, especially

the otolith-ocular reflex. The responses are called oVEMPs. Although a clinical

study suggested that oVEMPs are of vestibular origin, their exact origin is not clear

yet. The extent of the contribution of the saccule and utricule is controversial.

Further studies are required before this can be established as a definitive clinical

test. After establishing the neural pathway of oVEMPs, the combined use of

VEMPs and oVEMPs may be useful for assessing lesions in the brainstem, as

suggested by Rosengren et al. [31].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-44-320.jpg)

![VEMP Variants 41

Fig.

7.

Vestibular

evoked

extraocular

potentials

(oVEMPs)

and

vestibular

evoked

myogenic

potentials

(cVEMPs)

to

500-Hz

tone

bursts

[135-dB

sound

pressure

level

(dBSPL)].

(from

Fig.

3

of

ref.

30,

Elsevier,

with

permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-45-320.jpg)

![42 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Neurogenic Potentials

For recording VEMPs (including oVEMPs), cooperation of the subject (maintain-

ing contraction of the SCM or an upward gaze) is essential. Therefore, it is difficult

to record VEMPs in children and elderly people and impossible in sleeping or

generally anesthetized subjects. If possible, vestibular evoked neurogenic potentials

(VENPs), which do not require muscle contraction, may be preferable. It was

reported that negativity at a latency of 3 ms (N3) was observed instead of normal

waveforms during auditory brainstem response (ABR) recording in subjects with

profound hearing loss [32]. Ochi and Ohashi hypothesized that N3 might be of

saccular origin [33]. As the presence of N3 corresponded to the presence of VEMPs

[34] (Fig. 8), N3 might be of saccule origin.

However, it was difficult to visualize N3 in subjects with normal hearing because

they have normal ABR waveforms (Fig. 9). To visualize N3 in normal subjects, it

is necessary to suppress or delete ABR waveforms. For this purpose, we presented

white noise to the stimulated ear, the intensity of which was high enough to stimu-

late the cochlea but insufficient for the vestibular nerve. We hypothesized that this

ipsilateral masking sound could suppress ABRs by disturbing the synchronization

of the cochlear nerve to the target sound but that it would not affect VEMPs. Based

on this hypothesis, we recorded N3 in subjects with preserved hearing under

white noise exposure (Fig. 10).We presented 1000-Hz short tone bursts (130 dBSPL,

rise/fall time 0.5 ms, plateau time 1 ms) as target stimuli with white noise

(100 dBSPL). The recording electrodes were placed on the vertex and mastoid.

Signals were amplified and bandpass-filtered (100–3000 Hz). Responses to 500

stimuli were averaged. The stimulation rate was 10 Hz, and the time window for

recording was 10 ms. Under these conditions, the mean latency of N3 of healthy

subjects was 3.58 ms, and the mean threshold was 125 dBSPL. The appearance of

N3 under these conditions corresponded well with the appearance of VEMPs [35].

We assume that the source of N3 might be around the vestibular nucleus.

Apart from N3, Todd et al. recorded potentials on the scalp evoked by bone-

conducted sound, the intensity of which was higher than the threshold of VEMPs

Table 3. Rate of identifiable responses, amplitude, and latency of oVEMP

Parameter

0.1-ms click

(135 dBSPL)

500-Hz short tone burst

(135 dBSPL)

Ipsilateral

eye

Contralateral

eye

Ipsilateral

eye

Contralateral

eye

Rate of identifiable responses

(% of 20 ears)

0 50 45 90

Amplitude between nI and

pI (μV)a

— 3.2 ± 0.4 1.9 ± 0.2 7.0 ± 1.0

nI latency (ms) — 8.8 ± 0.3 12.8 ± 0.6 10.5 ± 0.1

pI latency (ms) — 14.5 ± 0.5 17.7 ± 0.9 15.9 ± 0.3

(from Table 1 of ref. 30, Elsevier, with permission)

a

Mean ± SE](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-46-320.jpg)

![44 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

[36]. In addition to auditory middle latency responses [37], the authors observed

positivity at about 10 ms (P10), which was maximum at Cz, and negativity at about

15 ms (N15), which was maximum at Fz. As P10 and N15 were also observed in

patients with bilateral profound hearing loss [38], these potentials are possibly

VENPs. The sources of these potentials and the origins at the end-organ level

should be clarified.

References

1. Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM (1992) Vestibular evoked potentials in human neck muscles

before and after unilateral vestibular deafferentation. Neurology 42:1635–1636

2. Colebatch JG, Halmagyi GM, Skuse NF (1994) Myogenic potentials generated by a click-

evoked vestibulocollic reflex. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 57:190–197

3. Kushiro K, Zakir M, Ogawa Y, et al (1999) Saccular and utricular inputs to sternocleidomas-

toid motoneurons of decerebrate cat. Exp Brain Res 126:410–416

4. Murofushi T, Ochiai A, Ozeki H, et al (2004) Laterality of vestibular evoked myogenic

potentials. Int J Audiol 43:66–68

5. Murofushi T, Takai Y, Iwasaki S, et al (2005) VEMP recording by simultaneous binaural

stimulation. Eur Ach Otorhinolaryngol 262:864–867

6. Halmagyi GM, Yavor RA, Colebatch JG (1995) Tapping the head activates the vestibular

system: a new use for the clinical reflex hammer. Neurology 45:1927–1929

7. Murofushi T, Matsuzaki M, Ikehara Y, et al (2000) Myogenic potentials on the neck muscle

by tapping the head. In: Claussen CF, Haid T, Hofferberth B (eds) Equilibrium research,

clinical equilibriometry and modern treatment. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 233–238

8. Brantberg K, Tribukait A (2002) Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in response to later-

ally directed skull taps. J Vestib Res 12:35–45

9. Brantberg K, Mathiesen T (2004) Preservation of tap vestibular evoked myogenic potentials

despite resection of the inferior vestibular nerve. J Vestib Res 14:347–351

10. Sheykholeslami K, Murofushi T, Kermany MH, et al (2000) Bone conducted evoked

myogenic potentials from the sternocleidomastoid muscle. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh)

120:731–734

11. Monobe H, Murofushi T (2004) Vestibular neuritis in a child with otitis media with effusion;

clinical application of vestibular evoked myogenic potential by bone-conducted sound. Int J

Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68:1455–458

Fig. 10. N3 in a healthy subject with ipsi-

lateral white noise exposure. The shaded

area represents period of stimulation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-48-320.jpg)

![Meniere’s Disease and Related Disorders:

Detection of Saccular Endolymphatic Hydrops

Introduction

Meniere’s disease (MD), a common inner ear disorder, is characterized by recurrent

vertigo attacks, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and a sensation of aural fullness

[1]. Guidelines for the diagnosis of MD have been published by the American

Academy of Otolaryngology, Head, and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) (Table 1) [2].

The incidence of MD varies from 21/100000 to 50/100000 [3–6]. MD develops

during middle age and shows a slight female predominance [7].

The combination of vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus were reported by Itard

(1821) [8]; and histopathological studies of the temporal bone in MD were pub-

lished in 1938 by Yamakawa [9] and Hallpike and Cairns [10]. They reported

endolymphatic hydrops in the temporal bone of MD patients at autopsy. According

to Schuknecht [11], during the early stage of the disease endolymphatic hydrops

involves principally the cochlear duct and the saccule. According to Okuno and

Sando [12], severe hydrops was observed in the saccule most frequently in their

histopathological study of the temporal bone. Therefore, a high incidence of abnor-

mal vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) in MD is expected.

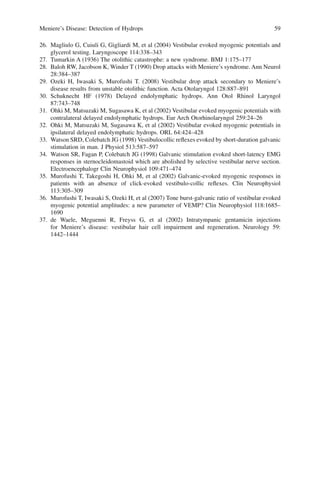

Incidence of Abnormal VEMPs in Meniere’s Disease

In earlier studies, the incidence of abnormal VEMPs was 39% according to Muro-

fushi et al. [13] and 54% according to de Waele et al. [14]. We reviewed results of

VEMPs of MD patients in our clinic (n = 81; 32 men, 49 women; ages 16–75 years,

mean 50.7 years; 95-dBnHL clicks). Among the 81 patients, 39 (48%) had absent

VEMPs on the affected side; 8 patients showed decreased VEMP amplitude; and

34 patients had normal VEMPs (Fig. 1). Thus, the overall incidence of abnormal

VEMPs in MD patients was 58%.

Although MD patients showed absent or decreased VEMPs, they rarely dis-

played delayed peaks [15]. Rauch et al. reported an elevated VEMP threshold in

Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potential: Its Basics and Clinical Applications. 49

Toshihisa Murofushi and Kimitaka Kaga

doi: 10.1007/978-4-431-85908-6_6, © Springer 2009](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-52-320.jpg)

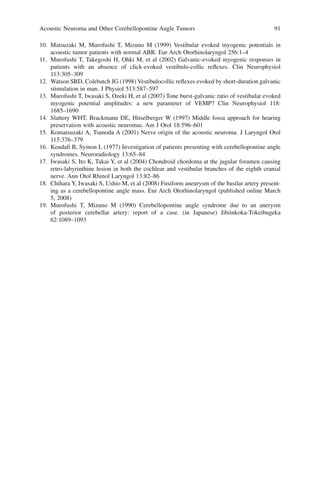

![50 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

MD patients and recommended that the threshold be a diagnostic parameter [16].

Rauch et al. also reported a shift of the best frequency of VEMP in MD patients.

According to previous studies, the best frequency of VEMP is between 300

and 700 Hz [17–19]. Whereas Rauch et al. reported that the best frequency is

500 Hz in healthy subjects, patients with MD showed less tuning at 500 Hz and

shifts of the best frequency to 1000 Hz [16]. We confirmed this tendency (Fig. 2).

Table 1. Dainostic scale for Meniere’s disease

Certain Meniere’s disease

Definite Meniere’s disease, plus histopathological confirmation

Definite Meniere’s disease

Two or more episodes of vertigo lasting at least 20 min

Audiometrically documented hearing loss on at least one occasion

Tinnitus or aural fullness

Probable Meniere’s disease

One definite episode of vertigo

Audiometrically documented hearing loss on at least one occasion

Tinnitus or aural fullness

Possible Meniere’s disease

Episodic vertigo without documented hearing loss

Sensorineural hearing loss—fluctuating or fixed—with disequilibrium but without definite

episodes

(from ref. 2)

In all scales, other causes must be excluded using any technical method

Absent

39 (48%)

Decreased

8 (10%)

Normal

33 (41%)

Increased

1 (1%)

Fig. 1. Vestibular evoked myogenic poten-

tial (VEMP) responses in Meniere’s disease

(MD) patients (n = 81)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-53-320.jpg)

![Meniere’s Disease: Detection of Hydrops 51

Rauch et al. attributed this shift to the change in resonant frequency in the saccule.

Comparison of the amplitudes and/or thresholds of VEMP in 500 Hz with those

in 1000 Hz could be a new parameter for VEMP that may be applicable to the

diagnosis of endolymphatic hydrops in the saccule. However, there have been

no reports concerning the specificity of this phenomenon. Thus, we need to

determine if this frequency shift is specific to Meniere’s disease or to endolym-

phatic hydrops.

Disease Stage and VEMPs

According to the guidelines of the AAO-HNS [2], the disease stage of MD is

determined by the average hearing level. Young et al. [19] studied VEMP results

in relation to the disease stage. Among 40 patients, 6 were classified as having

stage I MD. Five of the six patients showed normal VEMPs, and one had aug-

mented VEMPs on the affected side. Among the 12 patients classified as having

stage II MD, 7 had normal VEMPs, 2 had augmented VEMPs, 4 had decreased

VEMPs, and 2 had absent VEMPs. Among the 17 patients with stage III MD,

VEMPs were normal in 10, decreased in 4, and absent in 3. Among the five patients

classified as having stage IV MD, VEMPS were normal in two, decreased in one,

and absent in two. In that study, patients at advanced stages more frequently showed

absent or decreased VEMPs than patients at earlier stages.

Fig. 2. Frequency characteristics of VEMP responses in healthy subjects (n = 8). Among the

three tested frequencies (130 dBSPL), 500-Hz tone bursts tended to evoke the largest responses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-54-320.jpg)

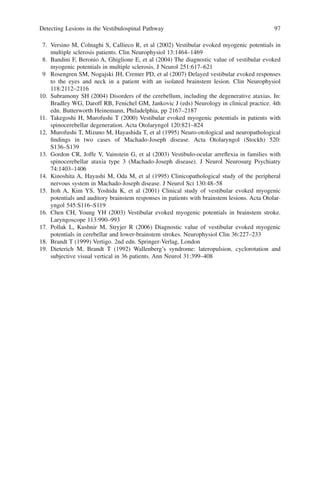

![52 Vestibular Evoked Myogenic Potentials

Proving Saccular Endolymphatic Hydrops Using VEMPs

Several clinical tests (e.g., electrocochleography, glycerol test, furosemide test)

have been utilized to provide evidence of endolymphatic hydrops [20–24].

Electrocochleography (ECochG) is a test of auditory evoked potentials, which

comprises potentials with short latencies (up to 2 ms). ECochG consists of

three components: cochlear microphonics (CM), summating potentials (SPs), and

compound action potentials (APs). The origin of CM and SPs is the cochlea,

whereas APs derive from the cochlear nerve. The (negative) SPs of MD patients

are significantly larger than those of healthy subjects [20, 21]. Such large SPs are

thought to reflect distention of the basilar membrane due to endolymphatic hydrops.

The ratio of the negative SPs to compound APs (CAPs) has been introduced as

a parameter. The upper limit of the normal range of the ratio SPs/CAPs has been

set at 0.30–0.40.

With the glycerol test, improvement of pure-tone hearing thresholds by glycerol

administration, an osmotic agent, has been thought to be caused by a temporary

reduction of endolymphatic hydrops in the cochlea [22, 23]. Endolymphatic hydrops

has been also reported to exist in the saccule [11, 12], although previous tests were

not able to prove it. Murofushi et al. [25], however, proposed the method to prove

the evidence of saccular hydrops in combination of VEMPs and glycerol adminis-

tration (glycerol VEMP test).

We record VEMPs prior to glycerol administration and 3 h after oral glycerol

administration (1.3 g/kg body weight) and measure the change ratio (CR) of the

VEMP (p13–n23) amplitudes.

CR (%) = 100(Aa − Ab)/(Aa + Ab)

where Aa is the p13–n23 amplitude 3 h after glycerol administration; and Ab is the

p13–n23 amplitude before glycerol administration.

The CR of six healthy volunteers was 3.52% ± 14.6% (mean ± SD). The normal

range was set at −25.7% to +32.7 % (within the mean ± 2 SD). Among the 17 MD

patients (4 men, 13 women; ages 24–72 years), 5 patients showed changes in VEMP

amplitudes exceeding the normal range (Fig. 3). Among the 17 patients, 10 had

abnormal VEMPs prior to glycerol administration. All the patients who showed

significantly large CRs had abnormal VEMPs prior to glycerol administration.

Therefore, 50% (5/10) of the patients with abnormal VEMPs showed significant

enlargement of VEMP amplitudes due to glycerol administration. Patients with

stage II MD most frequently had a positive glycerol VEMP test. The results of

glycerol VEMP testing were independent of the conventional glycerol test using

pure-tone audiometry. As glycerol VEMP testing can be performed simultaneously

with the conventional glycerol test, the glycerol VEMP test can provide supple-

mental information to detect endolymphatic hydrops [25, 26].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-55-320.jpg)

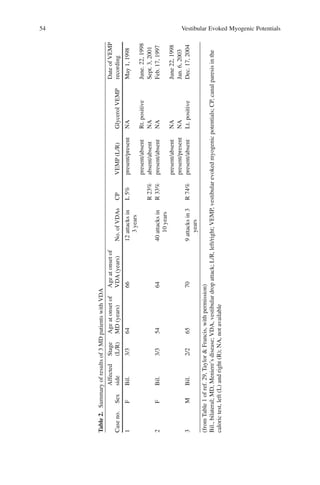

![Meniere’s Disease: Detection of Hydrops 53

Drop Attacks in MD and VEMPs

In 1936, Tumarkin was the first to describe sudden drop attacks in patients with

MD [27]. Patients with MD who suffered from drop attacks suddenly felt a sensa-

tion of being pushed to the ground and then fell without loss of consciousness [28].

This phenomenon has been called Tumarkin’s otolithic crisis or a vestibular drop

attack (VDA) [3]. It has been thought that VDA occurred with sudden changes in

endolymphatic fluid pressure with inappropriate otolith stimulation causing reflex-

like vestibulospinal loss of postural tone. The abnormal bursts of neural impulses

from the otolithic organs would pass through the lateral vestibulospinal tract

(LVST), resulting in loss of postural tone. These hypothesized pathophysiological

mechanisms allowed us to assume that the function of the otolithic organ might

have some room to change when VDA occurs. In other words, the functions of the

otolithic end-organs may be unstable.

Ozeki et al. reviewed clinical records of 116 MD patients, finding 3 with VDA

[29]. Profiles of the three patients are summarized in Table 2. All three patients

showed recovery of VEMP responses spontaneously (patient 2) or after glycerol

administration (patients 1 and 3). These results imply that abnormal VEMPs in

such patients can be reversible and that their otolithic organs might be unstable.

After the bilateral VEMPs of patient 1 disappeared, there were no more drop

attacks. At the advanced stage—when bilateral otolithic organs were irreversibly

damaged—VDA may no longer occur.

Fig. 3. Effects of oral glycerol in a 69-year-old woman with left MD. She showed increased

VEMP amplitudes on the left side 3 h after glycerol administration. post-G, after glycerol; pre-G,

before glycerol; L, left side; R, right side. (from Fig. 1 of ref. 25, Elsevier, with permission)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vemp-kaga-230911091840-210954b0/85/VEMP-KAGA-pdf-56-320.jpg)

![Meniere’s Disease: Detection of Hydrops 55

VEMPs in Delayed Endolymphatic Hydrops