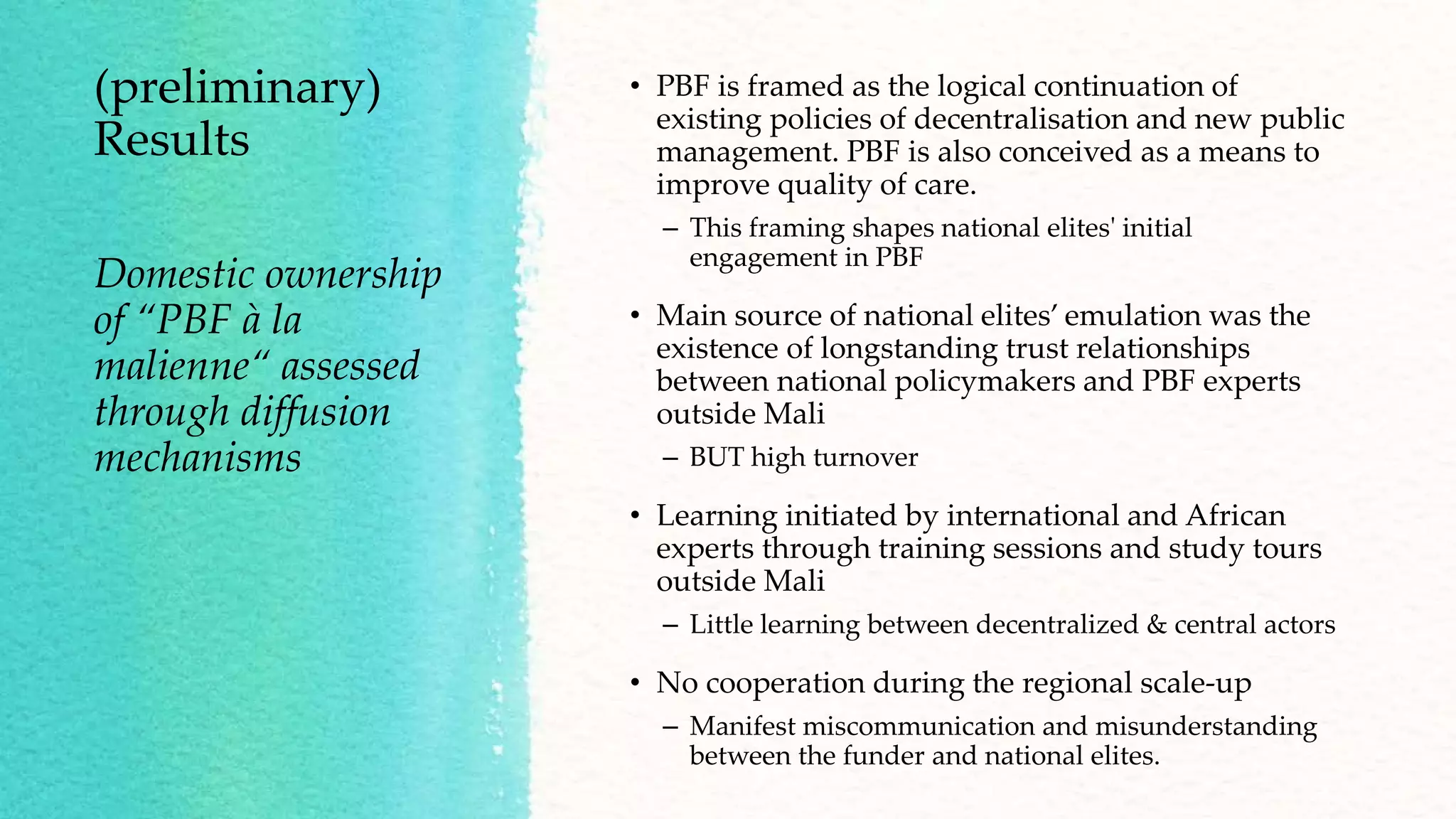

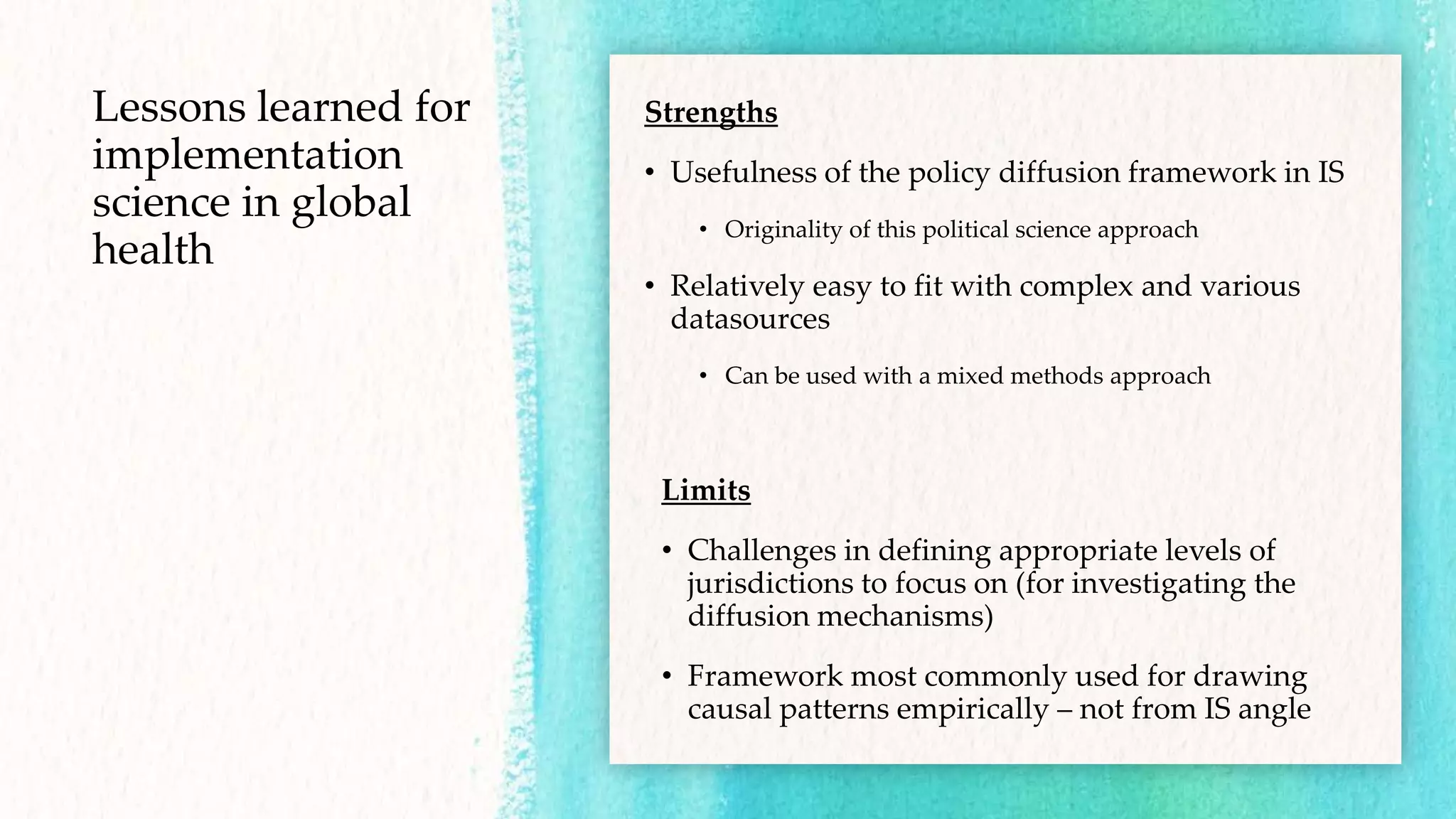

The document outlines a study investigating the diffusion and domestic ownership of performance-based financing (PBF) in Mali, highlighting the challenges and methods used. It discusses the diffusion mechanisms of policy emulation, learning, cooperation, and framing among national elites, revealing issues of miscommunication and limited collaboration during implementation. The study emphasizes the importance of a policy diffusion framework in understanding the integration of PBF within Mali's health policy landscape.