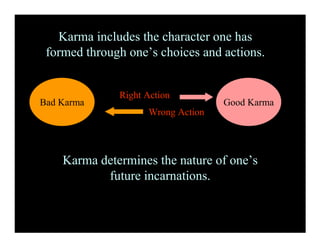

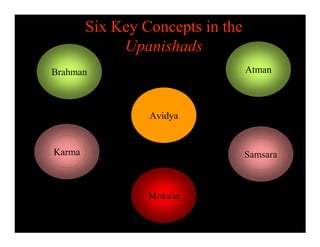

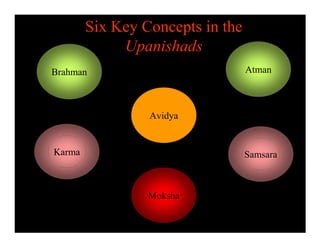

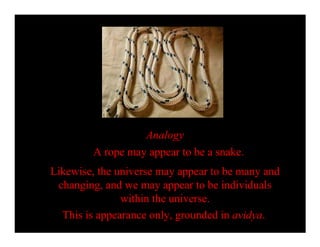

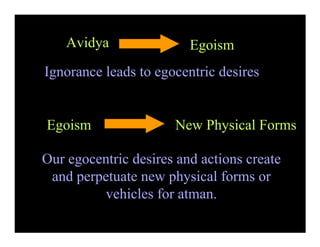

The Upanishads are sacred Hindu scriptures composed between 800-500 BCE that discuss the ultimate nature of reality. They teach that [1] Brahman is the single, eternal, unchanging reality beneath the illusion of multiplicity. Atman, the true self, is identical to Brahman. However, due to [2] avidya or ignorance, humans experience [3] samsara, the cycle of rebirth governed by [4] karma. The goal is to attain [5] moksha or liberation from samsara through enlightenment of the identity of Atman and Brahman.

![In itself Brahman cannot be defined or

positively described.

Ultimately “Brahman” is a way of

designating a state in which subject-object

duality ceases to exist.

“There is no better description [of

Brahman] than this: that it is not-this, it

is not-that (neti, neti).” Brhad-aranyaka

Upanishad, II, 3, 6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/upanishads-120205092819-phpapp02/85/Upanishads-18-320.jpg)

![Tat Tvam Asi

“Thou [Atman] art That [Brahman]”

(Chandogya Upanishad, VI)

There is a common consciousness between

Atman and Brahman.

“The individual self, apart from all

factors that differentiate it from pure

consciousness, is the same as the divine,

apart from its differentiating conditions.”

(Eliot Deutsch, Advaita Vedanta, p. 50)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/upanishads-120205092819-phpapp02/85/Upanishads-31-320.jpg)

![“By the mind alone is It [Brahman] to be perceived.

There is on earth no diversity.

He gets death after death,

Who perceives here seeming diversity.”

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, iv.iv.19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/upanishads-120205092819-phpapp02/85/Upanishads-41-320.jpg)