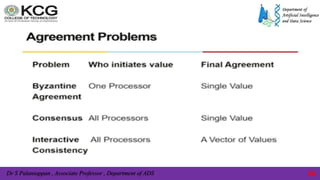

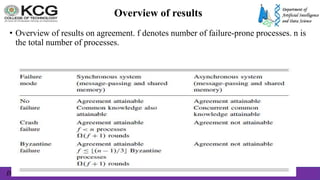

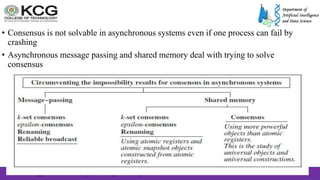

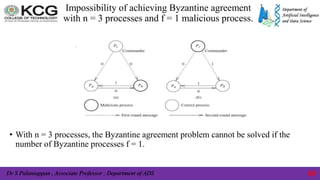

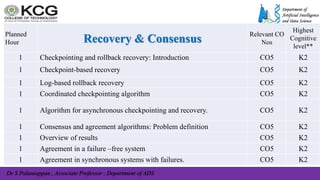

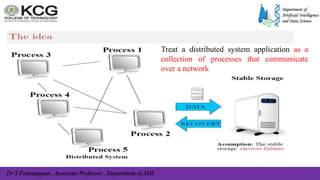

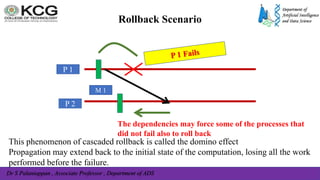

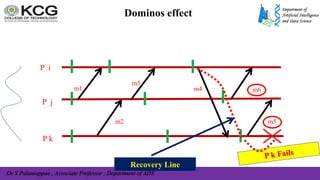

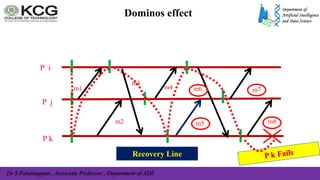

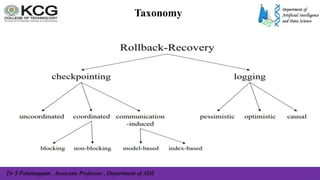

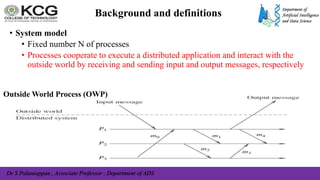

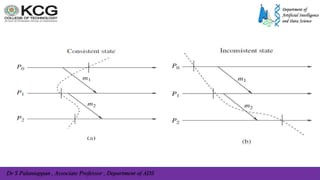

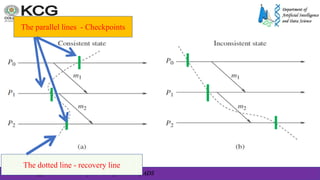

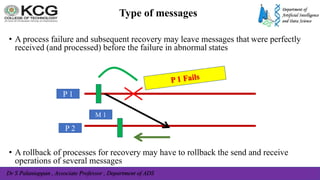

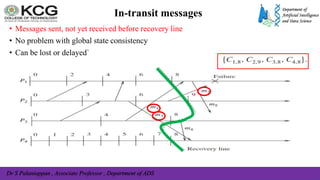

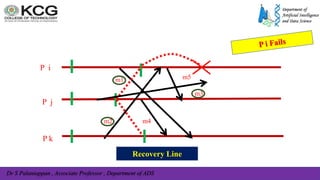

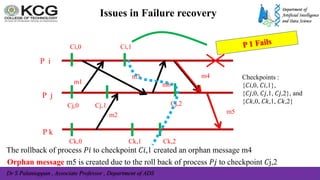

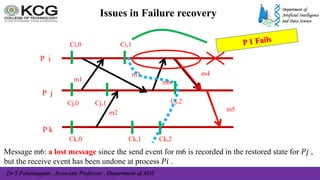

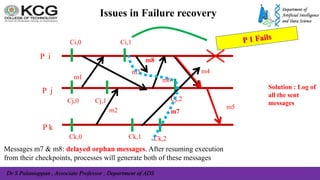

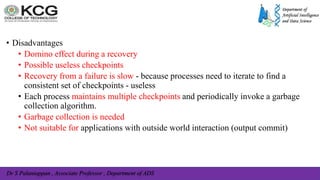

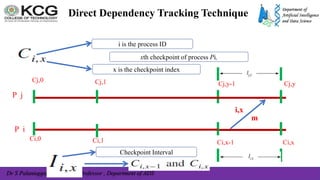

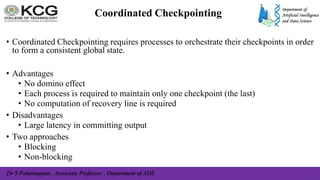

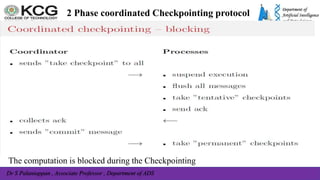

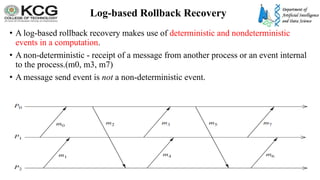

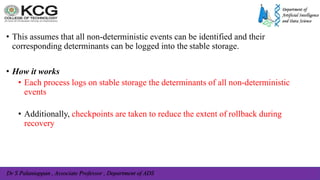

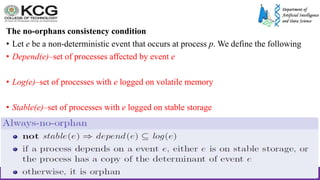

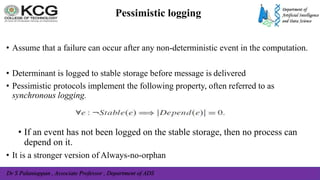

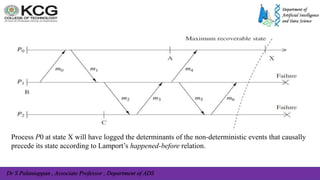

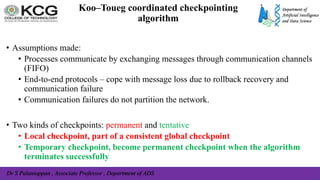

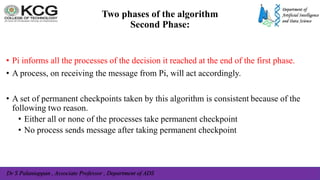

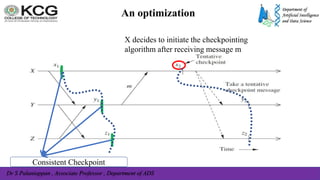

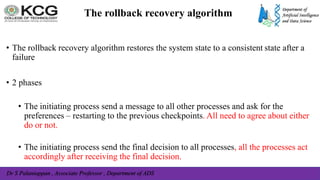

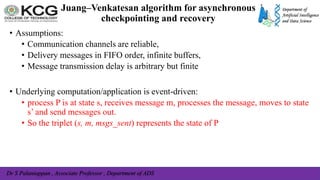

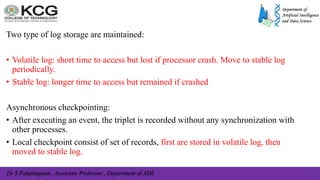

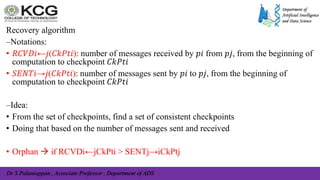

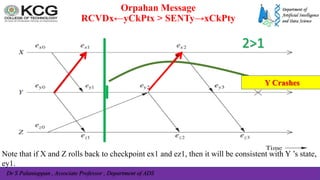

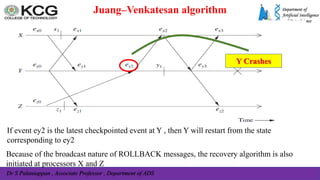

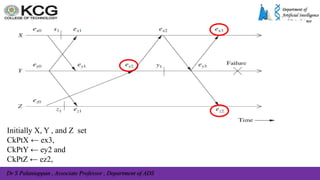

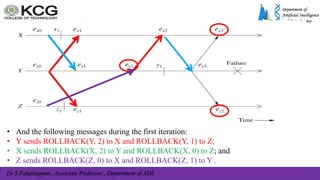

The document, authored by Dr. S. Palaniappan, covers topics related to recovery and consensus in distributed systems, emphasizing the importance of fault tolerance and rollback recovery methods. It discusses checkpointing techniques, including independent and coordinated checkpointing, and the implications of the domino effect during rollbacks. Additionally, it explores log-based rollback recovery and various algorithms designed to ensure consistent states in distributed applications.

![Dr S Palaniappan , Associate Professor , Department of ADS

The interactive consistency problem

• The interactive consistency problem differs from the Byzantine agreement problem

in that each process has an initial value, and all the correct processes must agree

upon a set of values, with one value for each process.

• Agreement All non-faulty processes must agree on the same array of values

A[v1…vn].

• Validity If process i is non-faulty and its initial value is vi, then all non faulty

processes agree on vi as the ith element of the array A. If process j is faulty, then the

non-faulty processes can agree on any value for Aj.

• Termination Each non-faulty process must eventually decide on the array A.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unitiv-240709080815-1c6503d6/85/unit-3-all-about-the-data-science-process-covering-the-steps-present-in-almost-every-data-science-project-85-320.jpg)