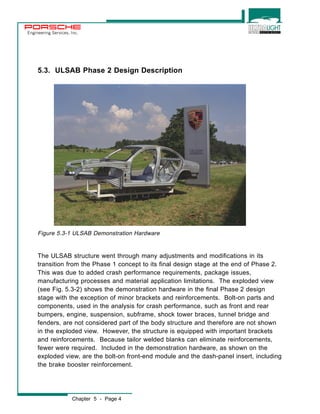

The ULSAB Phase 2 project validated concepts from Phase 1 by building demonstration hardware. Phase 2 achieved its goals of significant mass reduction compared to a reference vehicle, while meeting structural and crash performance targets. Testing showed the design exceeded Phase 1 targets for torsional and bending rigidity, and modal frequency. Mass reduction was 25% lower than the reference, and crash tests met new safety requirements. High strength steel use increased to 90% of the structure's mass. An economic analysis found the design could be produced at a similar or lower cost than conventional designs.

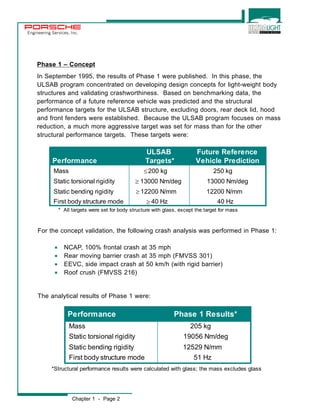

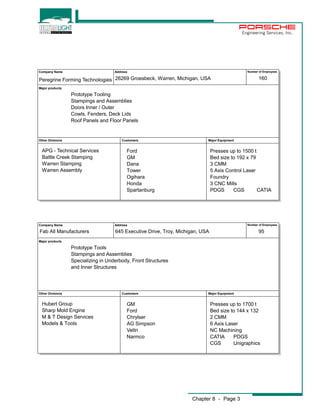

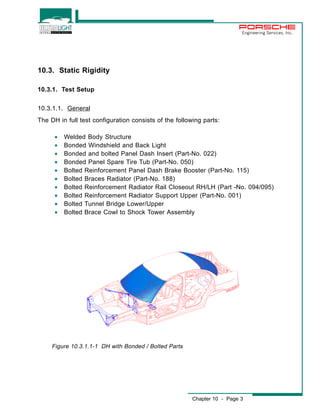

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Designed Brackets not Manufactured but

Considered Part of the ULSAB Structure

Part No Name Qty Calc Mass [Kg]

331 Bracket Exhaust Mount 2 0.060

332/333 Bracket Engine Mount RH/LH 2 0.528

334/335 Bracket Fender Mount Rear RH/LH 2 0.228

336 Bracket Battery Tray 1 0.412

337 Bracket Spare Tire Mount 1 0.089

338/339 Bracket Fuel Tank Mount Rear RH/LH 2 0.242

340 Bracket Front Tie Dow n Hook 2 0.236

341 Bracket Rear Tie Dow n Hook 2 0.236

342/343 Bracket Front Jack Support RH/LH 2 0.656

344/345 Bracket Rear Jack Support RH/LH 2 0.548

346 Bracket Plenum Support Center 1 0.445

N/A Weld Studs ~ 100 - 0.300

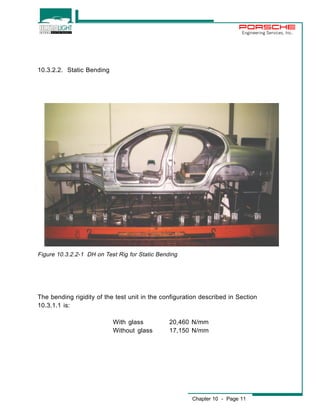

TOTAL 19 3.980

Chapter 5 - Page 11

Figure 5.3.2-2

Figure 5.3.2-3

Designed Reinforcements not Manufactured but

Considered Part of the ULSAB Structure

Part No Name Qty Calc Mass [Kg]

310 Reinf Hood Hinge Mount 2 0.086

311 Reinf Instrument Panel Beam Mount 2 0.134

312/313 Reinf Sub-Frame Front Mount 2 0.050

314/315 Reinf Sub-Frame Center Mount 2 0.116

316/317 Reinf Sub-Frame Rear Mount 2 0.418

318 Reinf Steering Rack Assembly Mount RH 1 0.032

319 Reinf Steering Rack Assembly Mount LH 1 0.041

320 Reinf Gear Shift Mount 1 0.271

321 Reinf Front Door Lock Striker 2 0.106

322 Reinf Front Door Check Arm 2 0.030

323 Reinf Rear Door Lock Striker 2 0.146

324 Reinf Rear Door Check Arm 2 0.028

325 Reinf Front D-Ring Adjustment 2 0.298

326 Reinf Rear Seat Cushion Mount 2 0.140

327 Reinf Rear Seat Latch 2 0.068

328 Reinf Rear Seat Back Mount Outer 2 0.278

329 Reinf Rear Seat Back Mount Center 1 0.035

330 Reinf Deck Lid Latch 1 0.136

TOTAL 31 2.413](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-76-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Reinforcements Manufactured and Welded to Structure

Part No Name Qty Mass [Kg]

038 Assy Reinf Floor Front Seat Rear Outer 2 0.120

110 Plate Rear Spring Upper 2 0.526

120 Reinf Floor Front Seat Rear Center 1 0.250

122 Reinf Rear Seat Inner Belt Mount 2 0.244

136 Reinf Panel Dash Upper 1 0.100

142 Assy Reinf Hinge Decklid 2 0.224

144 Reinf A-Pillar RH 1 0.229

145 Reinf A-Pillar LH 1 0.230

164 Assy Closeout Fender Support Rail RH 1 0.115

165 Assy Closeout Fender Support Rail LH 1 0.115

176 Hinge Base RH 4 0.650

177 Hinge Base LH 4 0.650

178 Hinge Stem 119 4 0.379

179 Hinge Stem 141 4 0.449

172 Assy Reinf Cowl Lower 1 0.127

190 Assy Reinf Seat Belt Retractor Rear 2 0.104

33 parts 4.512

Brackets Manufactured and Welded to Structure

Part No Name Qty Mass [Kg]

116 Assy Bracket Rear Shock Absorber Mount RH 1 0.335

117 Assy Bracket Rear Shock Absorber Mount LH 1 0.339

180 Bracket Trailing Arm Mount RH 1 0.333

181 Bracket Trailing Arm Mount LH 1 0.341

4 parts 1.348

Part No Name Qty Mass [Kg]

001 Assembly Reinf Radiator Support Upper 1 1.613

022 Panel Dash Insert 1 0.875

094 Reinf Radiator Rail Closeout RH 1 0.567

095 Reinf Radiator Rail Closeout LH 1 0.575

115 Reinf Panel Dash Brake Booster 1 0.464

188 Brace Radiator 2 0.250

7 parts 4.344

Chapter 5 - Page 13

Figure 5.3.3-2

Figure 5.3.3-3

Figure 5.3.3-4

Bolt-On Parts Manufactured and Attached to Structure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-78-320.jpg)

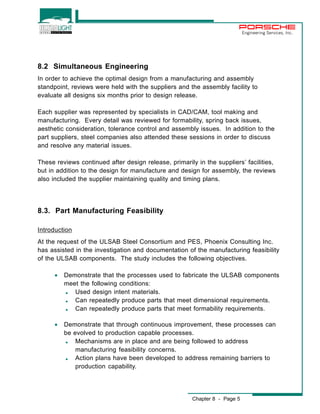

![Engineering Services, Inc.

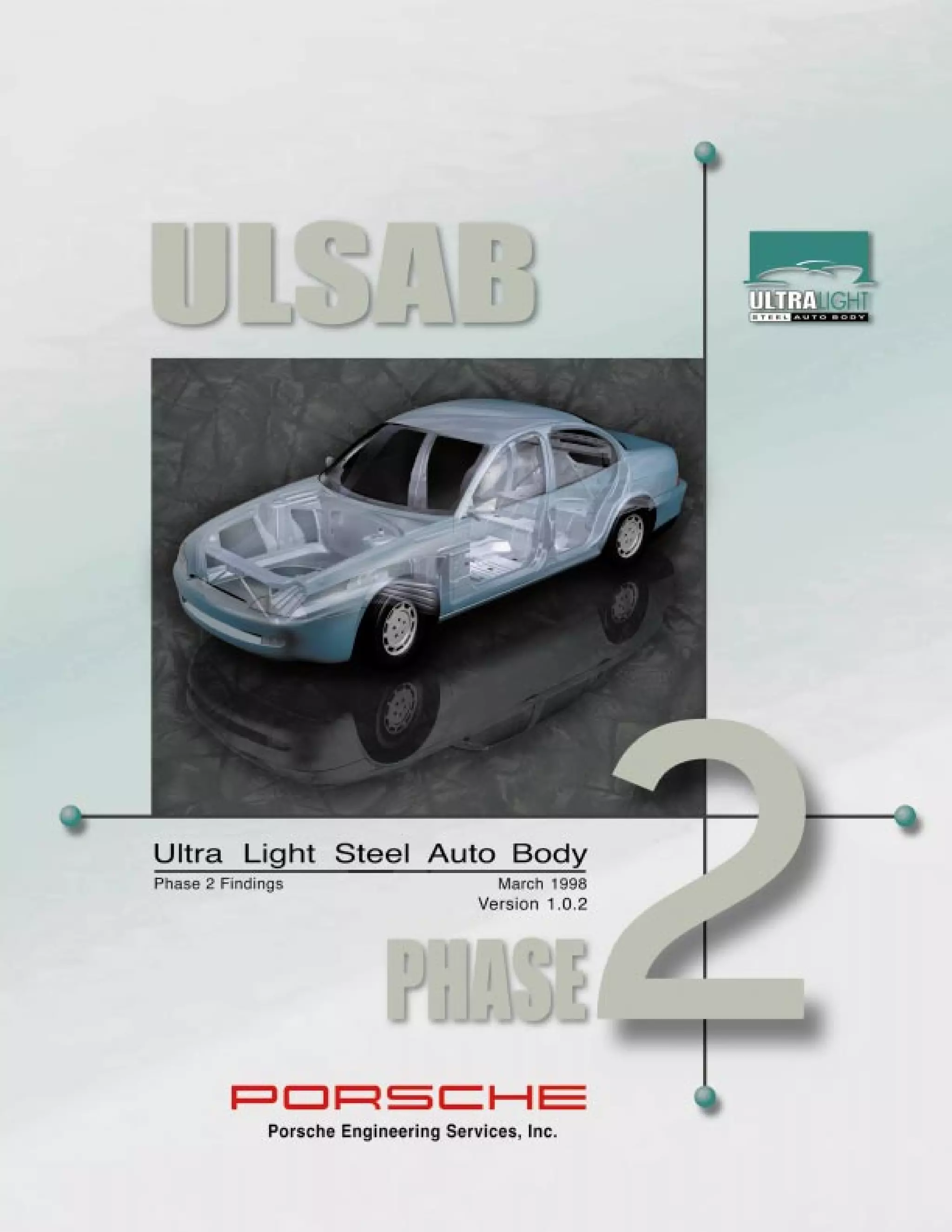

Figure. 5.4.1.2-4 Mass Reduction with Scalloped Flanges

Chapter 5 - Page 26

Part

Number

Part Name Calculated Part Mass

[kg]

Calculated Part Mass with

Scalloped Flange [kg]

Mass Reduction

[kg]

21 Panel Dash 6.180 6.140 0.040

28 Panel Cowl Lower 1.400 1.326 0.074

40 Pan Front Floor 15.934 15.892 0.042

45 Member Rear Suspension 1.486 1.440 0.046

55 Member Panel Back 1.450 1.424 0.026

68 Panel Wheelhouse Inner RH 2.141 2.110 0.031

69 Panel Wheelhouse Inner LH 2.141 2.110 0.031

81 Panel Package Tray Lower 1.700 1.594 0.106

140 Pan Rear Floor 4.330 4.298 0.032

0.428

5.4.1.3. Locator, Tooling and Electrophoresis Holes

Included in the detail part design are all locator holes for the assembly. All locator

holes needed for parts manufacturing and the holes necessary for the

electrophoresis of the body structure. After the location of the holes for

electrophoreses were first determined, they were then incorporated into the crash

models and the crash analysis was performed to verify that their position did not

have any negative influence on the crash performance. After this verification, the

holes were incorporated into the parts design.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-91-320.jpg)

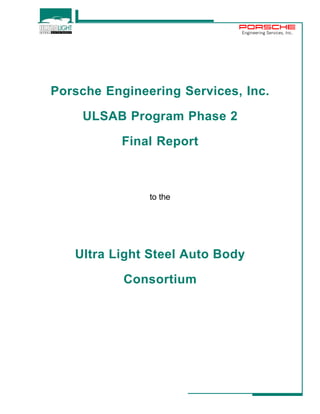

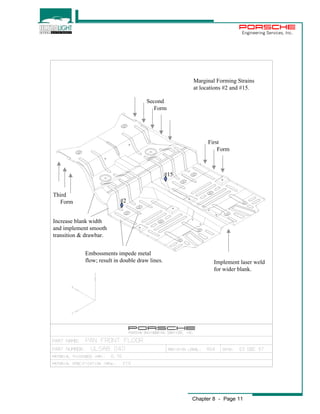

![Engineering Services, Inc.

0.08

0.07

0.06

0.05

0.04

0.03

0.02

0.01

0

21310 Nm/deg

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000 5500

0.03

0.02

0.01

0

-0.01

-0.02

-0.03

-0.04

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000 5500

Chapter 6 - Page 4

-0.05

Longitudinal X-axis [mm]

Derivation of Angle [deg/mm]

Support

Derivation of Torsion Angle

Shock Tower

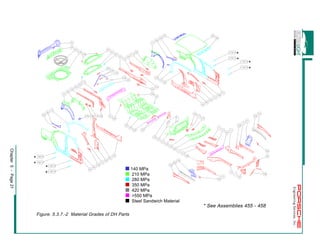

Front

Center, Spring

Attachment Rear

-0.01

Longitudinal X-axis [mm]

Angle = atan (zdisp/ycoor) [deg]

Support

Torsion Angle

Shock Tower

Front

Center, Spring

Attachment Rear

Figure 6.2.1-2 Torsion Angle vs. x-Axis

Figure 6.2.1-3 Derivation of Torsion Angle vs. x-Axis](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-98-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

0.25

0.2

0.15

0.1

0.05

0

-0.05

-0.1

-0.15

-0.2

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

20540 N/mm

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000 5500

Longitudinal X-Axis [mm]

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000 5500

Chapter 6 - Page 6

-0.4

Longitudinal X-Axis [mm]

Vertical Z-Displacement [mm]

Derivation of vertical Z-Displacement [mm]

Support

Derivation of Vertical Z-Displacement

Shock Tower

Front

Center, Spring

Attachment Rear

Figure 6.2.2-2 z-Displacement vs. x-Axis, Bending

Figure 6.2.2-3 Derivation of z-Displacement vs. x-Axis, Bending

Support

Vertical Z-Displacement

Shock Tower

Front

Center, Spring

Attachment Rear](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-100-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Subframe

Front Rail Ext.

Rocker

Rail Front

Fender S. Rail

55

50

85

115

50

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

Force (kN)

Figure 6.3.1-6 AMS Offset Crash Typical Cross Section Forces

Average Car Acceleration vs. Time

Rocker LHS / Tunnel / Rocker RHS

0 20 40 60 80 100

Chapter 6 - Page 15

-40

-30

-20

10

-0

+-10

10

time [ms]

ax [g]

Figure 6.3.1-7 AMS Offset Crash Acceleration vs. Time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-109-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

0 20 40 60 80 100

800

600

400

200

0

-200

Figure 6.3.1-8 AMS Offset Crash Deformation vs. Time

Chapter 6 - Page 16

time [ms]

sx [mm]

Car Deformation vs. Time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-110-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Average Car Acceleration vs. Time

Rocker LHS / Tunnel / Rocker RHS

0 20 40 60 80 100

time [ms]

Car Deformation vs. Time

0 20 40 60 80 100

Chapter 6 - Page 23

40

-40

30

-30

20

-20

-10

10

0

0

+10

-10

ax [g]

Figure 6.3.2-7 NCAP 100% Crash Acceleration vs. Time

800

600

400

200

0

time [ms]

sx [mm]

Figure 6.3.2-8 NCAP 100% Crash Deformation vs. Time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-117-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Rocker

Rear Rail

Rail Side Roof

Spare Wheel

50

80

15

20

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

Force (kN)

Figure 6.3.3-5 Rear Crash Typical Cross Section Forces (kN)

Average Car Acceleration vs. Time

0 20 40 60 80 100

Chapter 6 - Page 29

40

30

20

10

0

-10

time [ms]

ax [g]

Figure 6.3.3-6 Rear Crash Acceleration vs. Time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-123-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

0 20 40 60 80 100

800

600

400

200

0

Chapter 6 - Page 30

time [ms]

sx [mm]

Car Deformation vs. Time

Figure 6.3.3-7 Rear Crash Deformation vs. Time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-124-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

-1

-2

Chapter 6 - Page 36

Y - Intrusion [mm]

Y - Velocity [m/s]

Velocity vs. Intrusion

B-Pillar No 238

-2

Y - Intrusion [mm]

Y - Velocity [m/s]

Velocity vs. Intrusion

Door Inner Panel No 353

Figure 6.3.4-5 Side Impact Velocity vs. Intrusion at Node 353

Figure 6.3.4-6 Side Impact Velocity vs. Intrusion at Node 238](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-130-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

0 25 50 75 100 125 150

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

-5

Figure 6.3.5-3 Roof Crush Deformation vs. Force

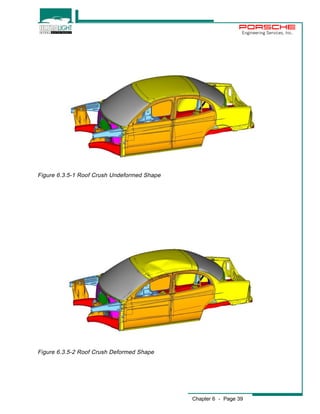

Analysis showed that 22.25 kN was reached within 30 mm of crush. The structure

resisted the applied load all the way up its peak of 36.15 kN and continued to

maintain it quite well even after peak, when it dropped to about 28 kN at 127 mm.

The load was well distributed through the A, B and C-pillars and down into the rear

rail.

6.4. CAE Analysis Summary

For the AMS Offset crash test the overall deformation and intrusion are the critical

figures. For the NCAP crash test, the critical figure is the vehicle crash pulse. The

target for the offset crash was to achieve low footwell intrusion. It is important to

achieve a good balance between these two targets. The results of the crash

analysis show that for the ULSAB a good compromise has been found to fulfill the

AMS as well as the NCAP frontal crash, considering the dependencies between

these two crash types.

To achieve the low footwell intrusion for the AMS crash a rigid front structure is

needed. A rigid front structure, however, means higher acceleration in the NCAP

Chapter 6 - Page 40

Deformation [mm]

Force [N]

Force vs. Deformation

127](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-134-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Test Unit Displacement Torsion

4000 Nm

3000 Nm

2000 Nm

1000 Nm

Front Axle Rear Axle

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

20

15

10

5

0

-5

Angle of Twist [min]

In general, the graph plot is running harmonic. There is only a jump in rigidity

between x = 3800 to x = 4200. This is related to the positive impact of the Member

Pass Through (Part-No. 090) to the torsional stiffness.

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

Front Axle Rear Axle

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

Chapter 10 - Page 7

Figure 10.3.2.1-2 Torsion Lines 4 Load Cases with Glass

Test Unit Gradient Torsion

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

Gradient [°/m

Figure 10.3.2.1-3 Gradient of Torsion Line with Glass

The above graph shows the gradient of the torsion line. The disharmonies of the

torsion line can be seen in a higher resolution.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-224-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

The torsional rigidity for DH #2 in the configuration described in section 10.3.1.1 is:

With glass 20,800 Nm/deg

Without glass 15,830 Nm/deg

20

15

10

5

0

Figure 10.3.2.1-4 Torsion Lines 4 Load Cases with Glass

As expected, the results are very close to the test unit.

This assumption is based on the test results without glass, because these are

nearly identical (15,790 Nm/deg vs. 15,830 Nm/deg).

Chapter 10 - Page 8

DH #2 Displacement Torsion

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

-5

Angle of Twist [min]

4000 Nm

3000 Nm

2000 Nm

1000 Nm

Front Axle Rear Axle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-225-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

DH #2 Gradient Torsion

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

Front Axle Rear Axle

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

Gradient [°/m]

The above graph shows the gradient of the torsion line. The disharmonies of the

torsion line can be seen in a higher resolution.

Chapter 10 - Page 9

Figure 10.3.2.1-5 Gradient of Torsion Line with Glass](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-226-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

To investigate the impact of several bonded and/or bolted parts, additional

measurements in various test configurations were undertaken with the test unit.

Test Configurations:

1. Full configuration as described in Section 10.3.1.1

2. As 1, but without braces radiator (Part-No. 188)

3. As 2, but without radiator support upper (Part-No. 001/094/095)

4. As 3, but without bolted brace cowl to shock tower assembly

5. As 4, but without tunnel bridge

110

100

90

80

100.0

Torsion Rigidity

As the numbers show, only the bolted brace cowl to shock tower assembly has a

significant impact on the torsional rigidity of 6.3%.

Chapter 10 - Page 10

98.3 98.3

92.0 92.0

Test Configuration

Torsion Rigidity [%]

1 2 3 4 5

Figure 10.3.2.1-6 Torsion Rigidity Five Test Configurations](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-227-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Test Unit Displacement Bending

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

Figure 10.3.2.2-2 Bending Lines 4 Load Cases with Glass

The graph is running harmonic. There is only a local increase in bending rigidity

between x = 3500 and x = 4200. This indicates a stiff joint between rocker and rear

rails. Furthermore, Porsche relates this to the design of the side roof rail.

Test Unit Average Deviation Bending

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

50

40

30

20

10

0

-10

-20

Figure 10.3.2.2-3 Deviation from the Average Bending Line with Glass

The above graph shows the deviation from the average value of the bending line.

The disharmonies can be seen in a better resolution.

Chapter 10 - Page 12

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

-30

Deviation from the average [%]

Front Axle Rear Axle

-0.5

Vertical Displacement [mm]

4000 N

3000 N

2000 N

1000 N

Front Axle Rear Axle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-229-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

The bending rigidity for DH #2 in the configuration described in Section 10.3.1.1 is:

With glass 18,100 N/mm

Without glass 15,950 N/mm

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

-0.1

-0.2

-0.3

-0.4

Figure 10.3.2.2-4 Bending Lines 4 Load Cases with Glass

The bending lines show the same characteristics as for the test unit, but the

absolute value decreased by 11%. The local increase between x=3500 and x=4200

is not so evident as it was on the test unit. This could be created by local

modifications of the side roof rail and the rear rails for improved manufacturing.

Furthermore, the material gage of the panel roof changed from 0.77mm to 0.70mm

due to material availability problems for the test unit; this was also a factor for the

decrease of the absolute value.

Additionally Porsche has experienced that static rigidities of body structures differ

by plus/minus five percent (5%) even under series production conditions.

Chapter 10 - Page 13

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

-0.5

Vertical Displacement [mm]

4000 N

3000 N

2000 N

1000 N

Rear Axle

DH #2 Displacement Bending

Front Axle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-230-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000

50

40

30

20

10

0

-10

-20

-30

-40

Figure 10.3.2.2-5 Deviation from the Average Bending Line with Glass

The above graph shows the deviation from the average value of the bending line.

The disharmonies can be seen in a better resolution.

Chapter 10 - Page 14

Longitudinal Axis X [mm]

-50

Deviation from the average [%]

DH #2 Average Deviation Bending

Front Axle Rear Axle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-231-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

To investigate the impact of several bonded and/or bolted parts, additional

measurements were undertaken:

Bending Rigidity

Figure 10.3.2.2-6 Bending Rigidity Five Test Configurations

Chapter 10 - Page 15

110

100

90

80

100.0 100.0 99.0 98.8 100.0

Test Configuration

Bending Rigidity [%]

1 2 3 4 5

Test Configurations:

1. Full configuration as described in Chapter 10.3.1.1

2. As 1, but without braces radiator (Part-No. 188)

3. As 2, but without radiator support upper (Part-No. 001/094/095)

4. As 3, but without bolted brace cowl to shock tower assembly

5. As 4, but without tunnel bridge

As the numbers show, none of these parts display a significant impact on bending

rigidity.

The increase from test configuration four (4) to test configuration five (5) is caused

by local effects of the tunnel bridge to the displacement of the rocker. This behavior

was also noticed in other body structures.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-232-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

The global modes of the test unit in the described test configuration can be seen in

the following chart:

70

60

50

40

49.1

Test Unit Modal Analysis

60.8

The dynamic rigidity of the ULSAB structure is remarkably good, as it was already

indicated by the static test results. Windshield and backlight have a significant

impact on the first torsion mode. The difference is in the same range, as known

from other sedan body structures.

The effect on first bending and first front-end lateral mode is relatively small. For

the test configuration with glass, the first torsion mode and the first front-end lateral

mode are coupled at 60.6 Hz.

Chapter 10 - Page 19

Figure 10.4.2-2 Modal Analysis Results - Test Unit

64.3

60.6

62.4

60.6

First Modes [Hz]

Torsion Bending Front End Lateral

without glass with glass](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-236-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Test Unit Modal Analysis with Screens

Frequency Response Function Amplitude [(m/s2)/N]

First Bending 62.4 Hz

Corner Points

50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

Figure 10.4.2-3 Frequency Response Functions - Test Unit

The graph plot above shows the frequency response functions, measured at the

four driving points. Second bending mode at 63.5 Hz occurs mainly in the rear;

whereas the first bending mode occurs in the front and rear of the structure.

Chapter 10 - Page 20

2

Test Unit Modal Analysis with Screens

Frequency Response Functions, measured at the body corner points

Power input by means of electrodynamic shakers at the body corner points

Frequency [Hz]

0

First Torsion 60.6 Hz Bending 63.5 Hz

Front Left

Front Right

Rear Left

Rear Right](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-237-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

The global modes for DH #2 in the described test configuration can be seen in the

following chart:

70

60

50

40

47

DH #2 Modal Analysis

57.2

The dynamic rigidity of DH #2 is in the same range as the values of the test unit.

The front-end lateral mode changed remarkably. This is created by the change of

the material gauge of the rail fender support inner from 0.9mm to 1.2mm.

The torsion mode and bending mode without glass decreased slightly, but with

glass, the loss of dynamic rigidity is compensated.

Chapter 10 - Page 21

Figure 10.4.2-4 Modal Analysis Results - DH #2

66.5

60.1

63.9 64.9

First Modes [Hz]

Torsion Bending Front End Lateral

w ithout glass w ith glass](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-238-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

DH #2 Modal Analysis with Screens

Frequency Response Functions, measured at the body corner points

Power input by means of electrodynamic shakers at the body center points

4

3.8

3.6

3.4

3.2

3

2.8

2.6

2.4

2.2

2

1.8

1.6

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

Figure 10.4.2-5 Frequency Response Functions - DH #2

Measurement Points:

Body Corner Points

Driving Points:

Body Corner Points

ulsabdh2

ULSAB_DH2_mS

The graph plot above shows the frequency response function, measured at the four

driving points. The amplitude of the first bending increased in relation to the test

unit. This is in correlation with the decrease of the static bending rigidity.

Additional modal analysis was conducted on the ULSAB structure, to investigate the

influence of several bolted and/or bonded parts.

Test configurations:

1. Full test configuration as described in chapter 10.3.1.1.

2. As 1, but without bolted brace cowl to shock tower assembly

3. As 2, but without braces radiator (Part-No.188)

4. As 3, but without tunnel bridge

5. As 4, but without radiator support upper (Part-No. 001/094/095)

Chapter 10 - Page 22

Front Left

Front Right

Rear Left

Rear Right

50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64 66 68 70

18-12-97

ULSAB DH2

Body Structure

with Screens

Project:

Test:

Date:

Vehicle:

Frequency Hz

Frequency Response Function Amplitude [(m/s2)/N]

First Bending 63.9 Hz

First Torsion 60.1 Hz](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-239-320.jpg)

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Modal Analysis

62.4 62.4 62.4 62.3 62.3

60.6 61.0 61.0 60.8 60.3

Chapter 10 - Page 23

70

60

50

40

60.6

47.0 47.3 47.2

53.4

Test Configuration

First Modes [Hz]

1 2 3 4 5

Front End Lateral Torsion Bending

Figure 10.4.2-6 Modal Analysis Five Test Configurations

The influence of the bolted brace cowl to shock tower assembly on the front-end

lateral mode of 13.6 Hz is evident.

Test configuration 5 shows an improvement in the front-end lateral mode, but this is

mainly caused by the influence of the mass of assembly radiator support.

The other modifications have no evident impact on dynamic rigidity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-240-320.jpg)

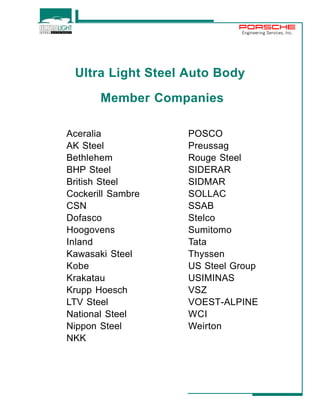

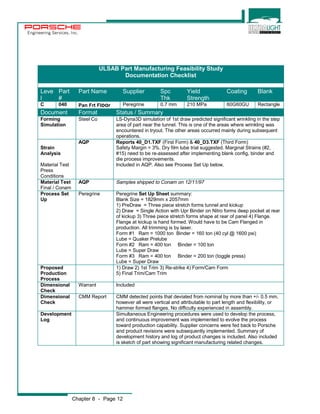

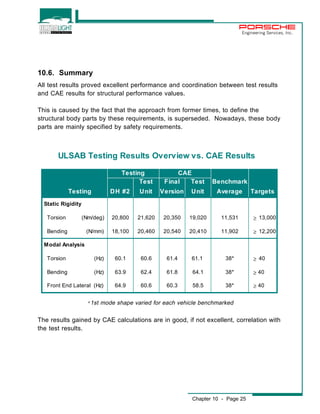

![Engineering Services, Inc.

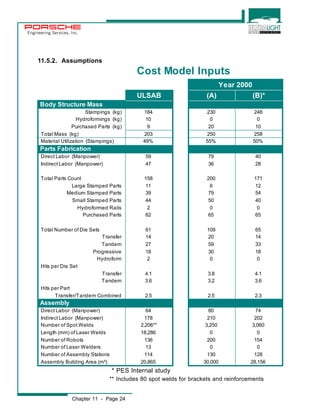

Phase 2 Benchmark Difference

Performance Results Average Difference (%)

Mass (kg) 203 271 - 68 - 25%

Static Torsional Rigidity (Nm/deg) 20800 11531 + 9269 + 80%

Static Bending Rigidity (N/mm) 18100 11902 +6198 + 52%

First Body Structure Mode (Hz) 60 38 + 22 + 58%

Chapter 12 - Page 1

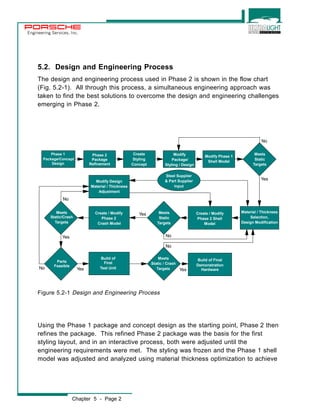

12. Summary of Phase 2 Results

The Phase 2 of the ULSAB program has come to its conclusion with the build of the

demonstration hardware.

The test results of the demonstration hardware are remarkable.

Figure 12-1 Structural Performance Summary

Relative to the benchmark average vehicle mass of 271 kg, the mass reduction

achieved is 68 kg (25%).

The static torsional rigidity exceeds the target. The efficiency (rigidity / mass) has

increased, in relation to Phase 1, to 102.5 [(Nm/deg)/kg] (Fig. 12-2). The Phase 2

structural performance results are shown in the graphs as a tolerance field rather

than a fixed point. To indicate that the mass and the performances can vary from

one demonstration hardware structures to another, as it would also do in real mass

production. The static bending rigidity as well as the first body structure mode have

also been increased in comparison to the Phase 1 results (Fig. 12-3 and 12-4).

These high levels of static and dynamic rigidity provide an excellent basis for a

complete vehicle development in respect to its NVH behavior.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-271-320.jpg)

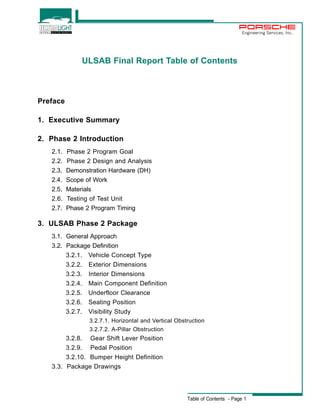

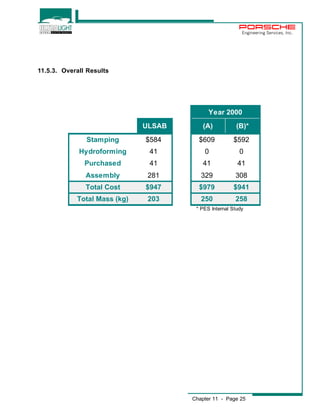

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Torsional Rigidity vs. Mass

110 100 90 80

180 200 220 240 260 280 300 320 340

24

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

4

Figure. 12-2 ULSAB Phase 2 Torsional Efficiency

Bending Rigidity vs. Mass

ULSAB

Phase II

70

60

50

40

30

ULSAB 40

Target

180 200 220 240 260 280 300 320 340

24

22

20

18

16

14

12

10

8

6

Chapter 12 - Page 2

70

60

50

Cb (x1000) [N/mm]

Cb/m

110 100 90 80

m [kg]

All data adjusted to target vehicle

Cb with Glass, m without Glass

Reference Vehicles: Acura Legend, BMW 5 series, Chevrolet Lumina, Ford Taurus, Honda Accord, Lexus LS 400,

Mazda 929, Mercedes Benz 190 E, Toyota Cressida

4

30

20

Future

Performance

Reference

Current

Average

ULSAB

Phase I

18.1

203

Figure. 12-3 ULSAB Phase 2 Bending Efficiency

20

Future

Performance

Reference

Current

Average

Cb (x1000) [Nm/deg]

Ct/m

m [kg]

All data adjusted to target vehicle

Cb with Glass, m without Glass

Reference Vehicles: Acura Legend, BMW 5 series, Chevrolet Lumina, Ford Taurus, Honda Accord, Lexus LS 400,

Mazda 929, Mercedes Benz 190 E, Toyota Cressida

ULSAB

Target

ULSAB

20.8 Phase I

203

ULSAB

Phase II](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-272-320.jpg)

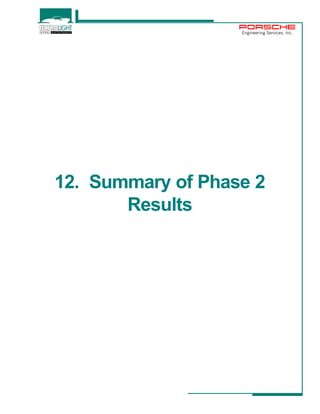

![Engineering Services, Inc.

Future

Performance

Reference

ULSAB

Phase II

180 200 220 240 260 280 300 320 340

Chapter 12 - Page 3

70

65

60

55

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

ULSAB

Target

Current

Average

f [Hz]

First Body Structure Frequency vs. Mass

m [kg]

Lowest global frequency

f with Glass, m without Glass

Reference Vehicles: Acura Legend, Chevrolet Lumina, Ford Taurus, Honda Accord, Lexus LS 400,

Mazda 929, Toyota Cressida

ULSAB

Phase I

60.1

203

Figure. 12-4 ULSAB Phase 2 Frequency Efficiency

The results of the crash analysis confirmed the integrity and safety of the ULSAB

structure. The AMS Offset Crash is considered one of the most severe crash tests

of today. In recently performed comparison crash tests of AMS, with the same

vehicle towards a deformable barrier with 40% offset at 64 km/h versus the AMS

Offset Crash barrier with 50% offset at 55 km/n, the results were nearly equal. This

confirms that the decision to analyze the ULSAB structure for its offset crash

behavior using the AMS test configuration, determined at the beginning of Phase 2

in 1995, was the right choice.

The NCAP 100% Frontal Crash was run at 35 mph, 5 mph above the federal

requirement of FMVSS 208, meaning 36% more energy had to be absorbed.

In both the 50% Offset and 100% Front Crash low footwell intrusion and structural

integrity proved the safety of the structure.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ulsabengrptcomplete-141013204259-conversion-gate01/85/Ulsab-engineer-report-complete-273-320.jpg)