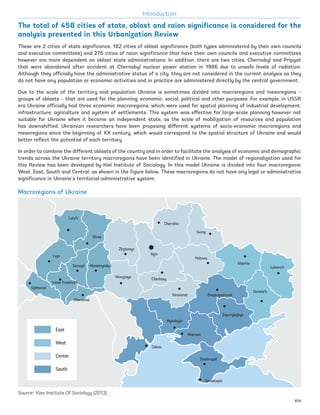

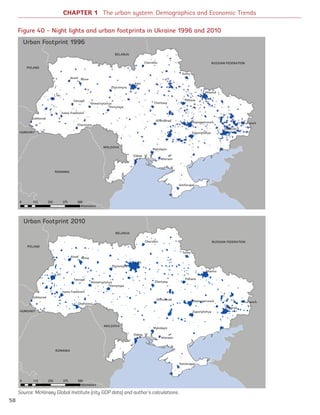

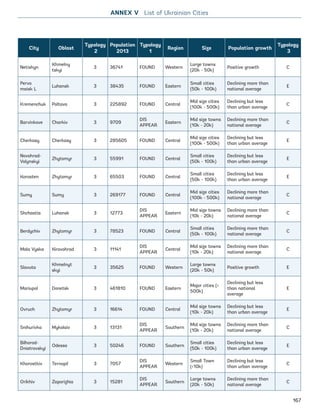

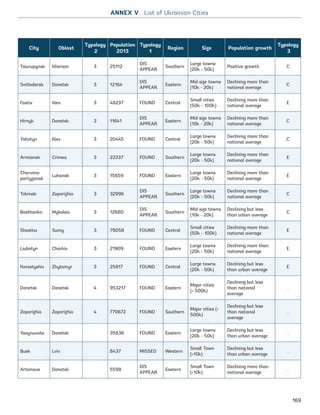

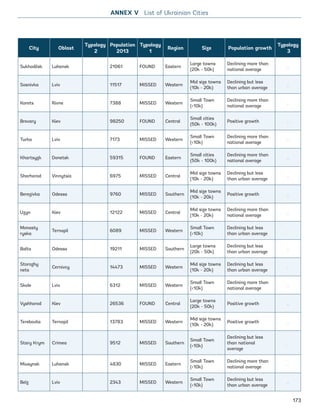

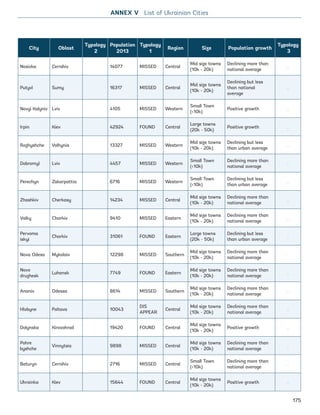

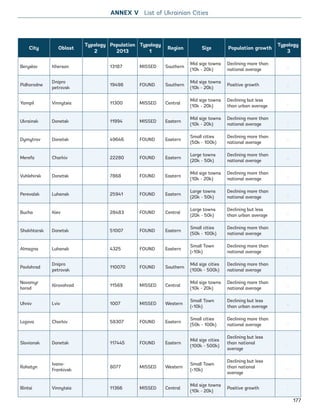

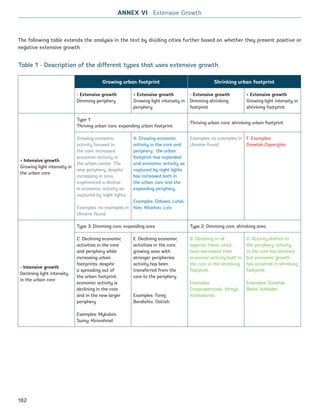

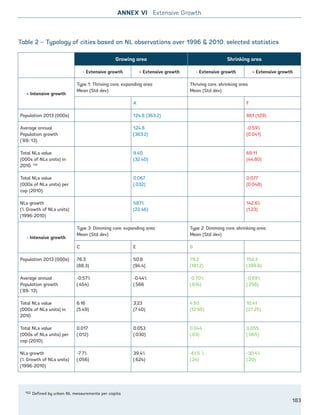

This document is a report by the World Bank on urbanization in Ukraine. It provides an overview of demographic and economic trends in Ukrainian cities and regions. Some key findings include:

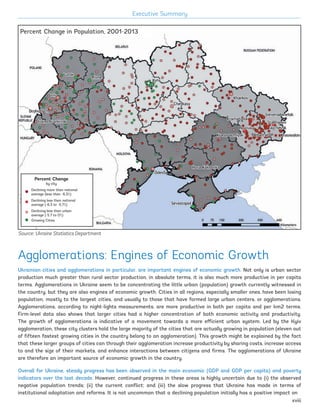

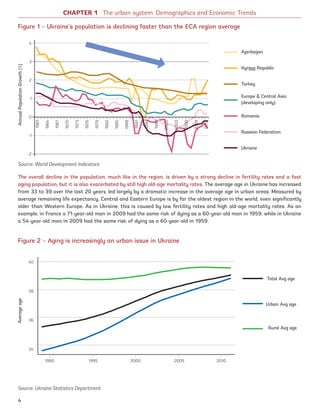

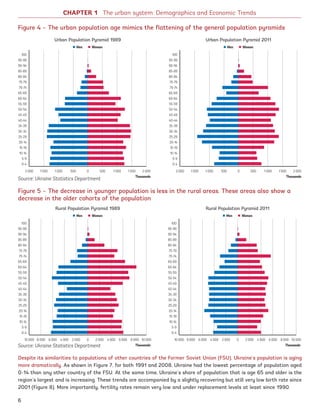

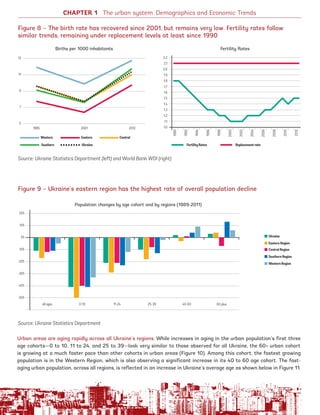

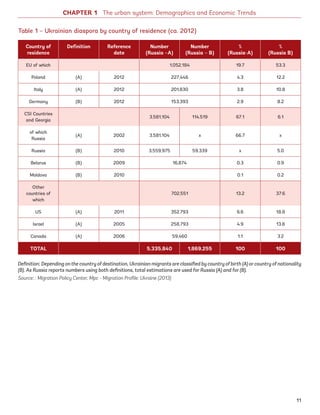

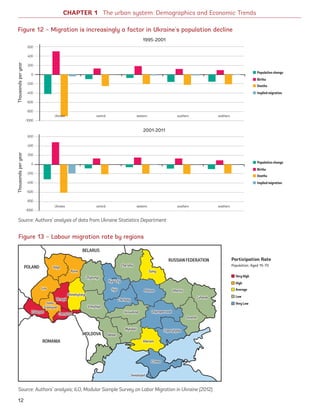

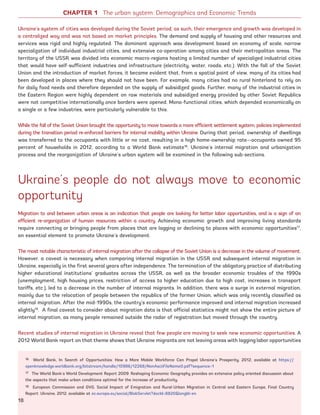

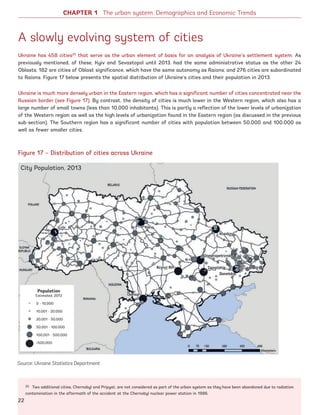

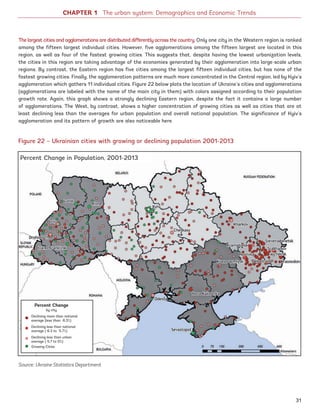

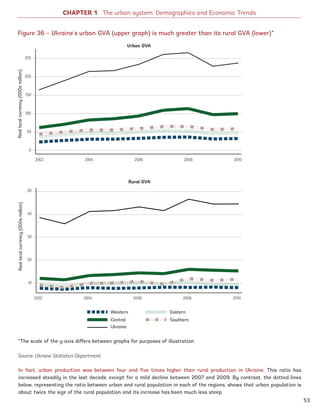

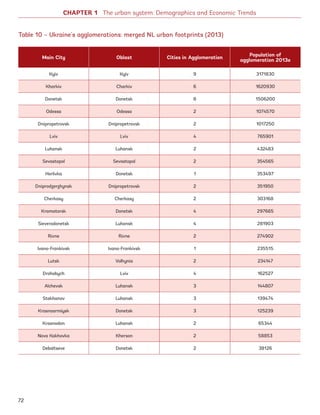

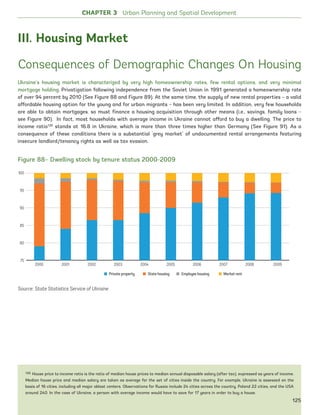

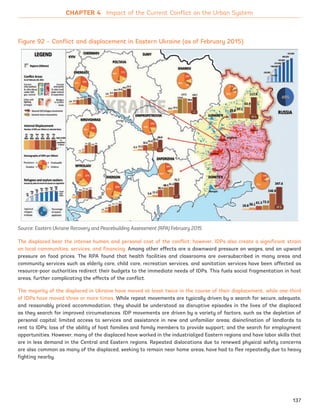

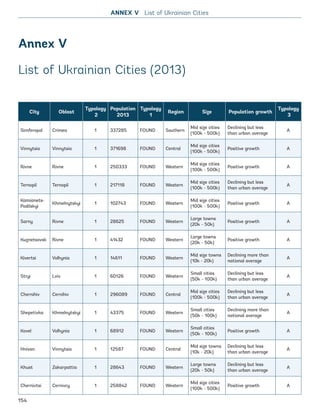

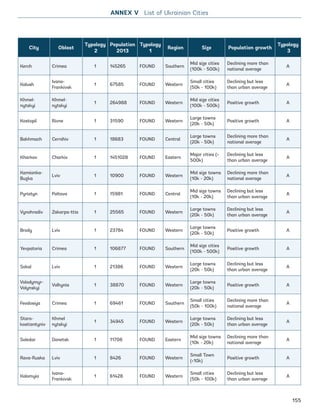

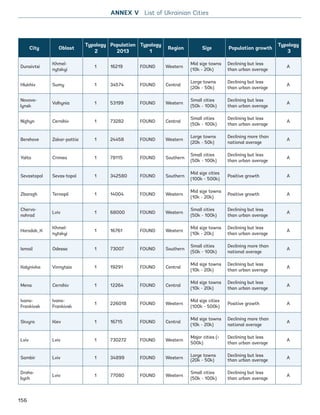

- Ukraine's population is declining rapidly, aging, and experiencing high rates of labor migration. This is impacting both urban and rural areas.

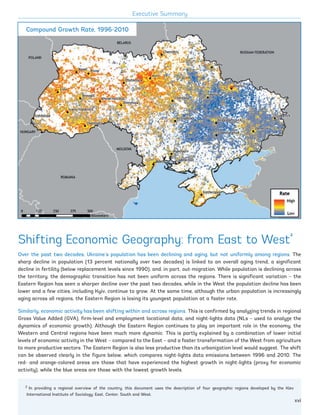

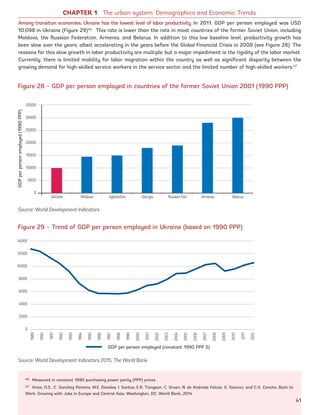

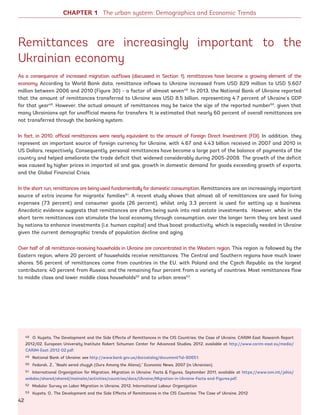

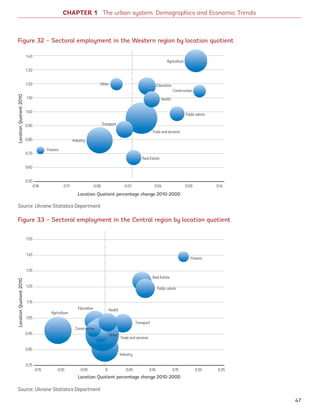

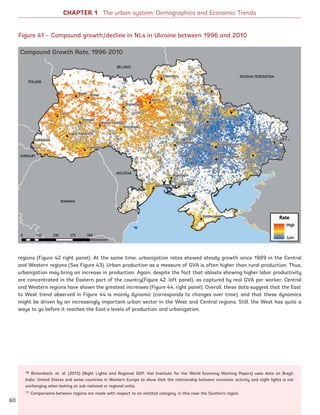

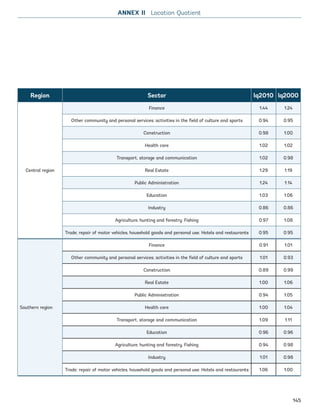

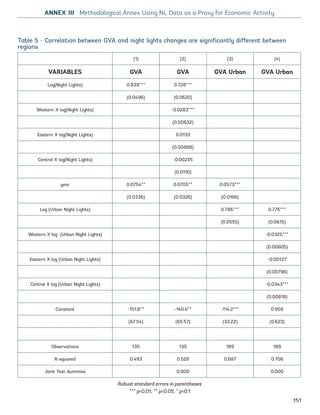

- The economy has shifted from industrial to service-based, but industry still plays an important role. However, economic growth varies significantly between regions.

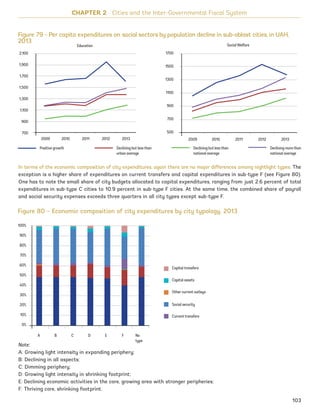

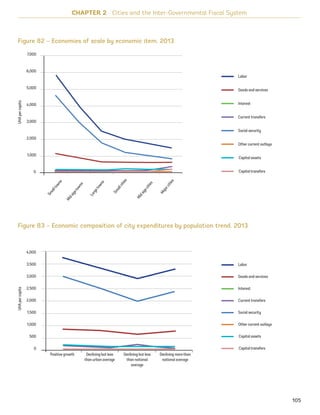

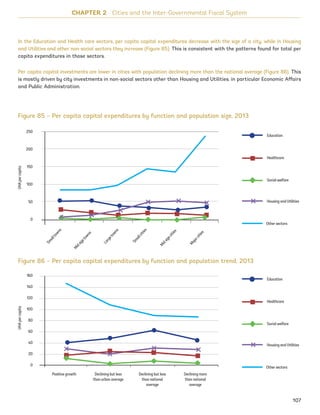

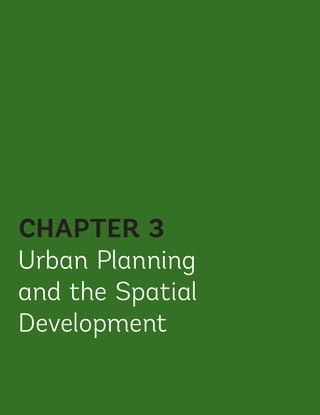

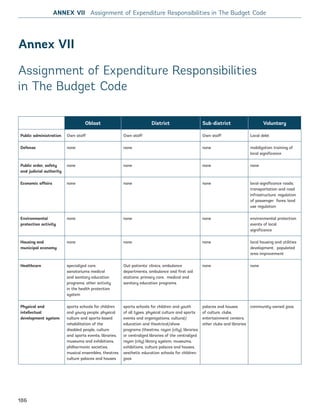

- Cities face fiscal challenges due to their large social spending responsibilities and reliance on intergovernmental transfers in the decentralized system. Planning and management of urban growth and decline is also an issue.