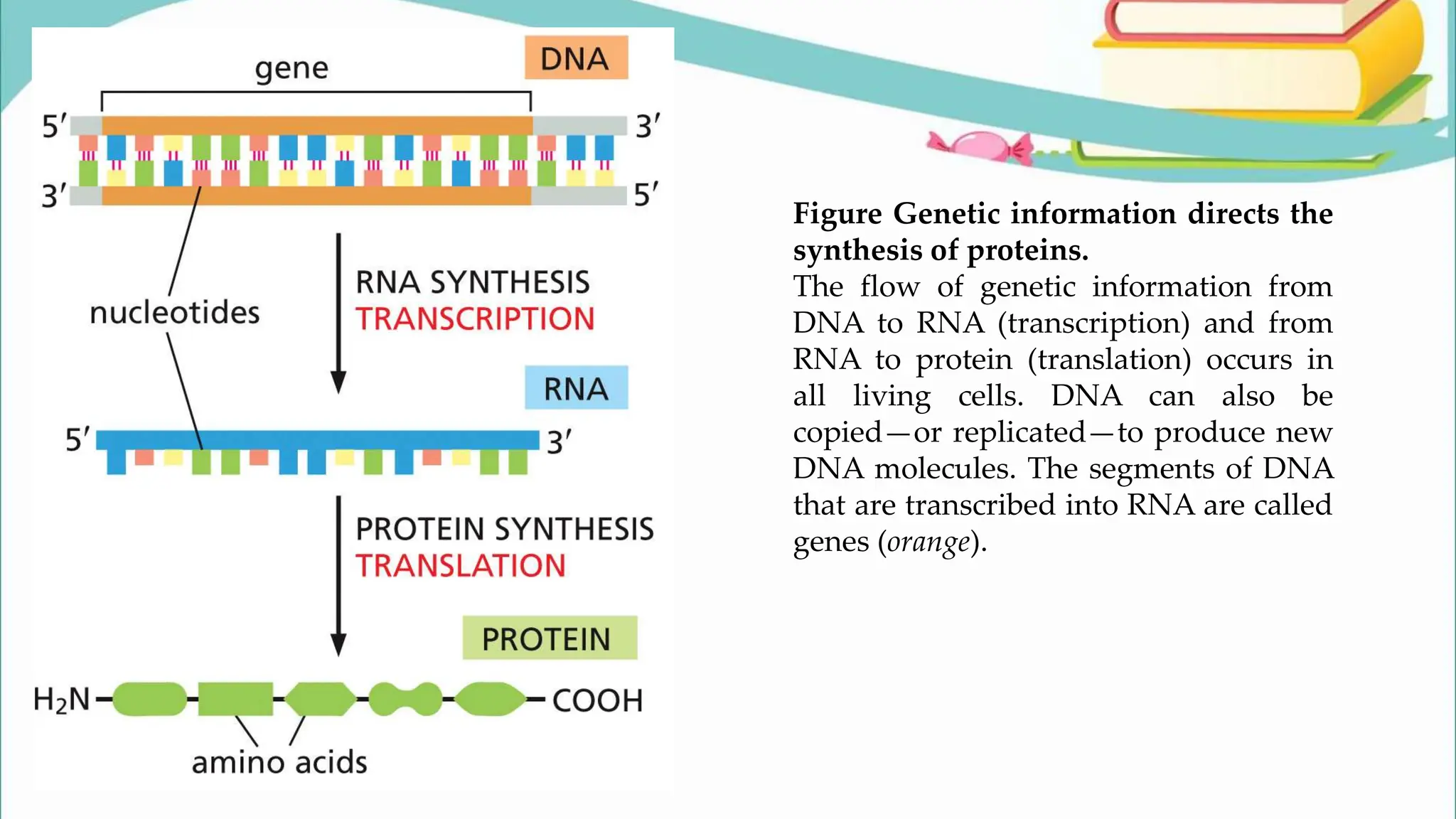

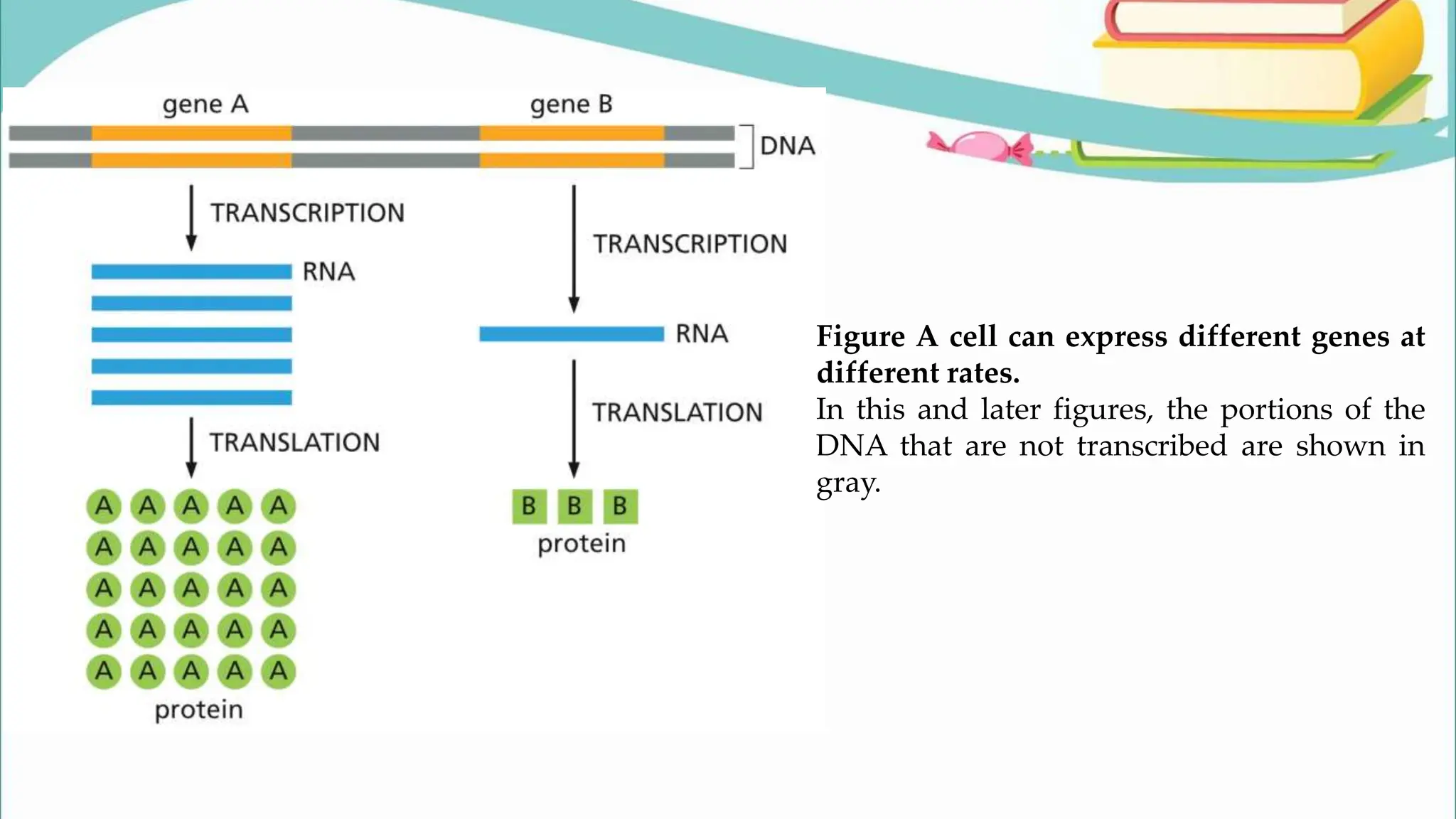

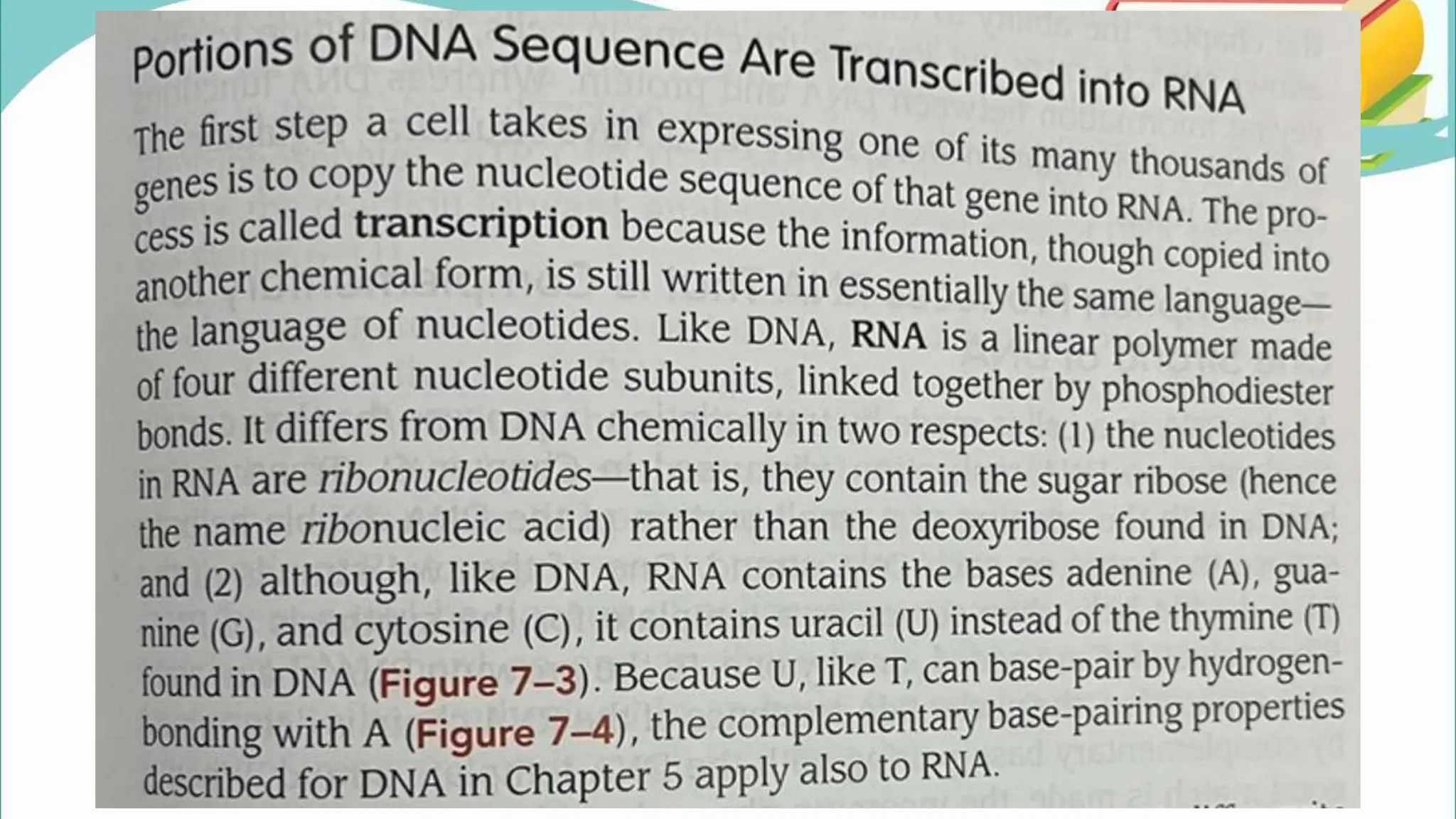

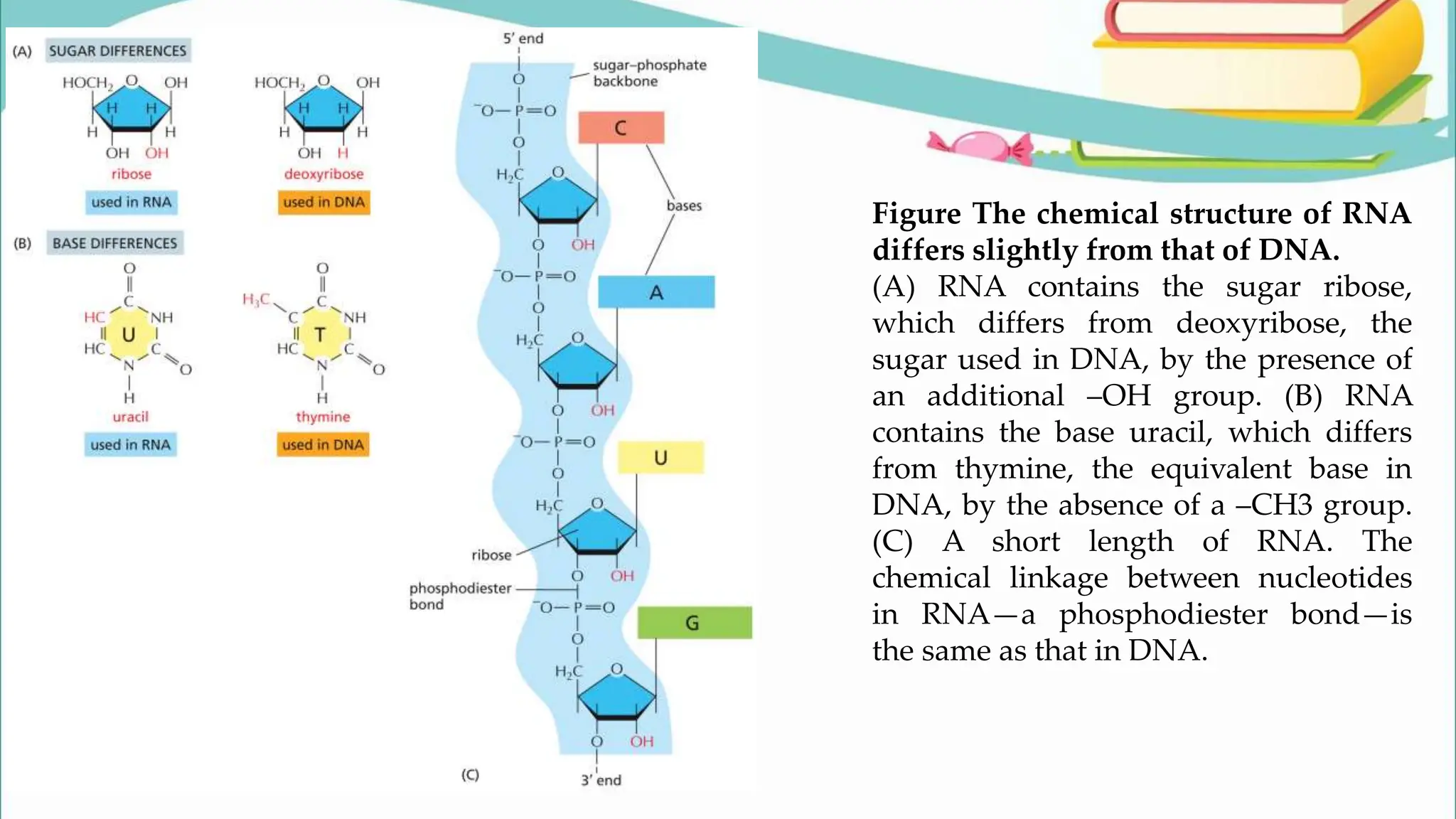

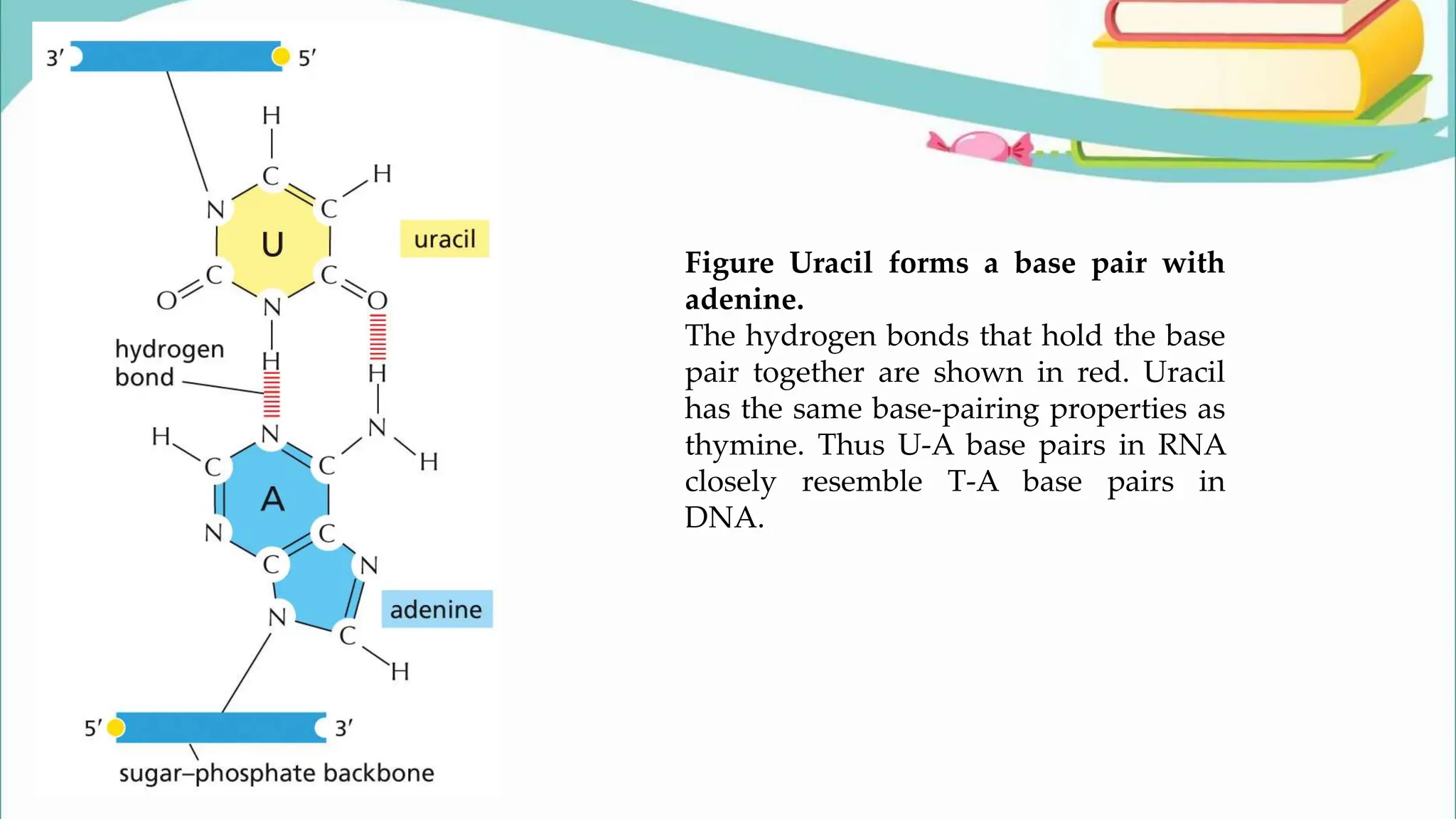

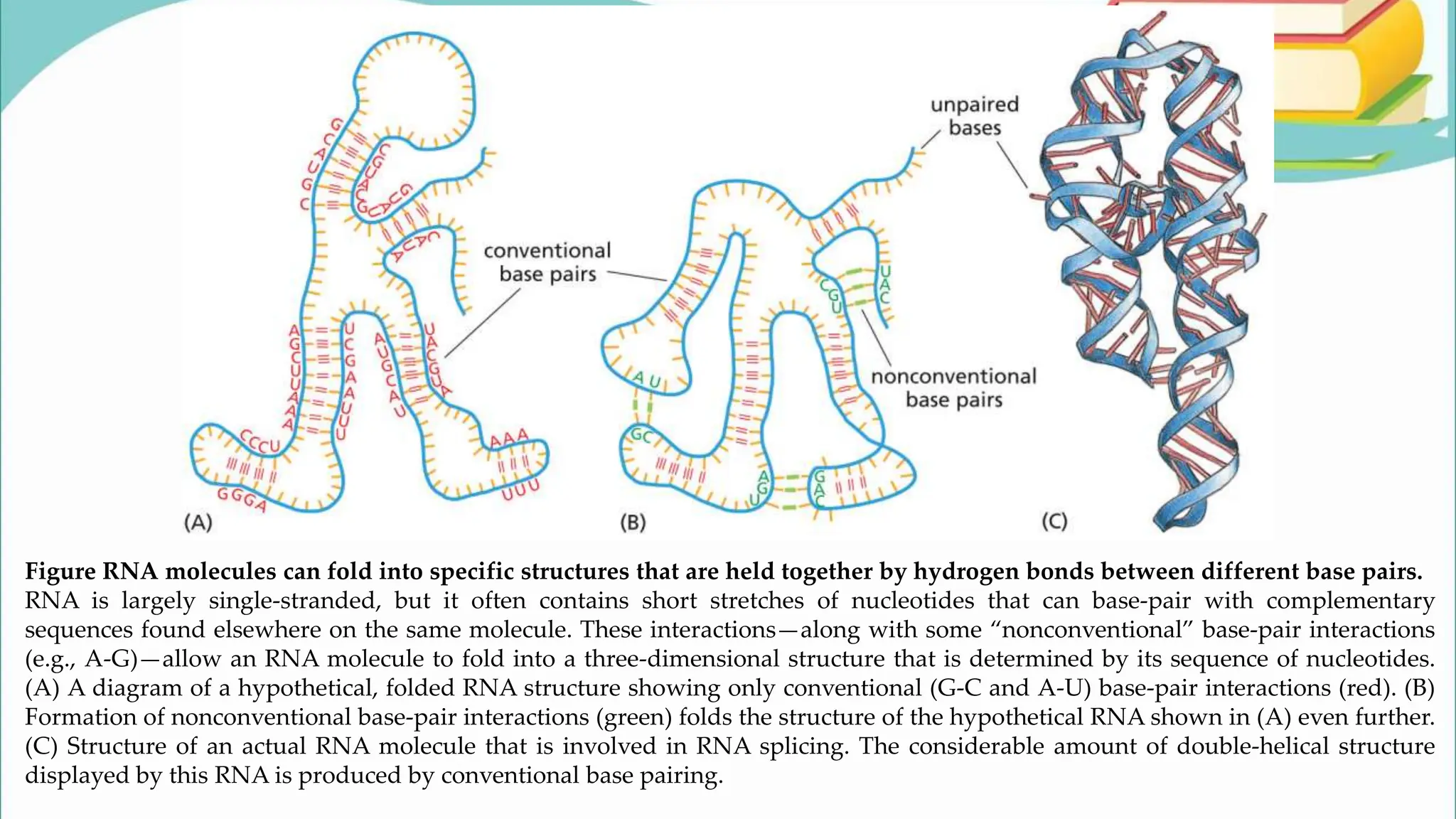

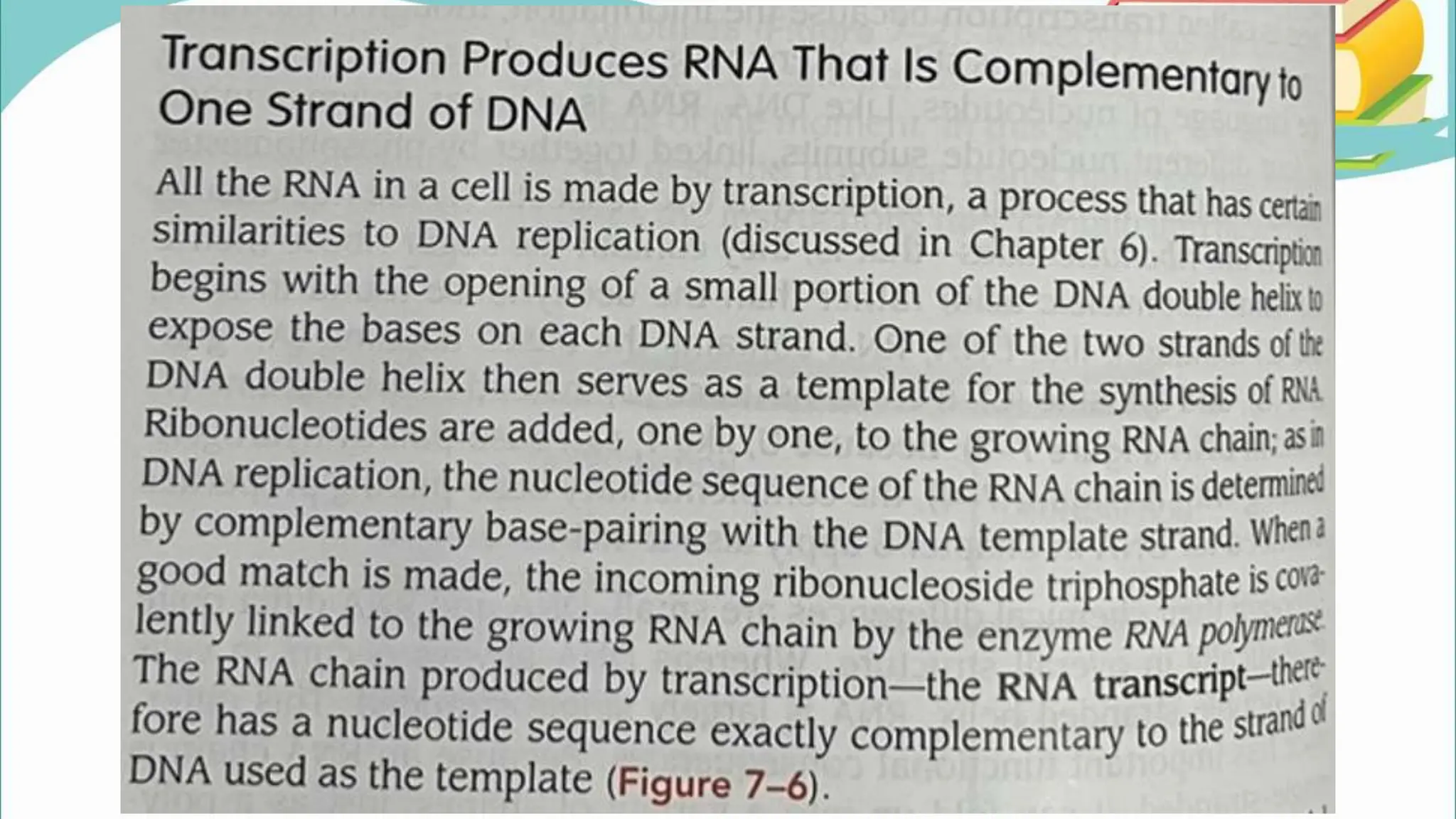

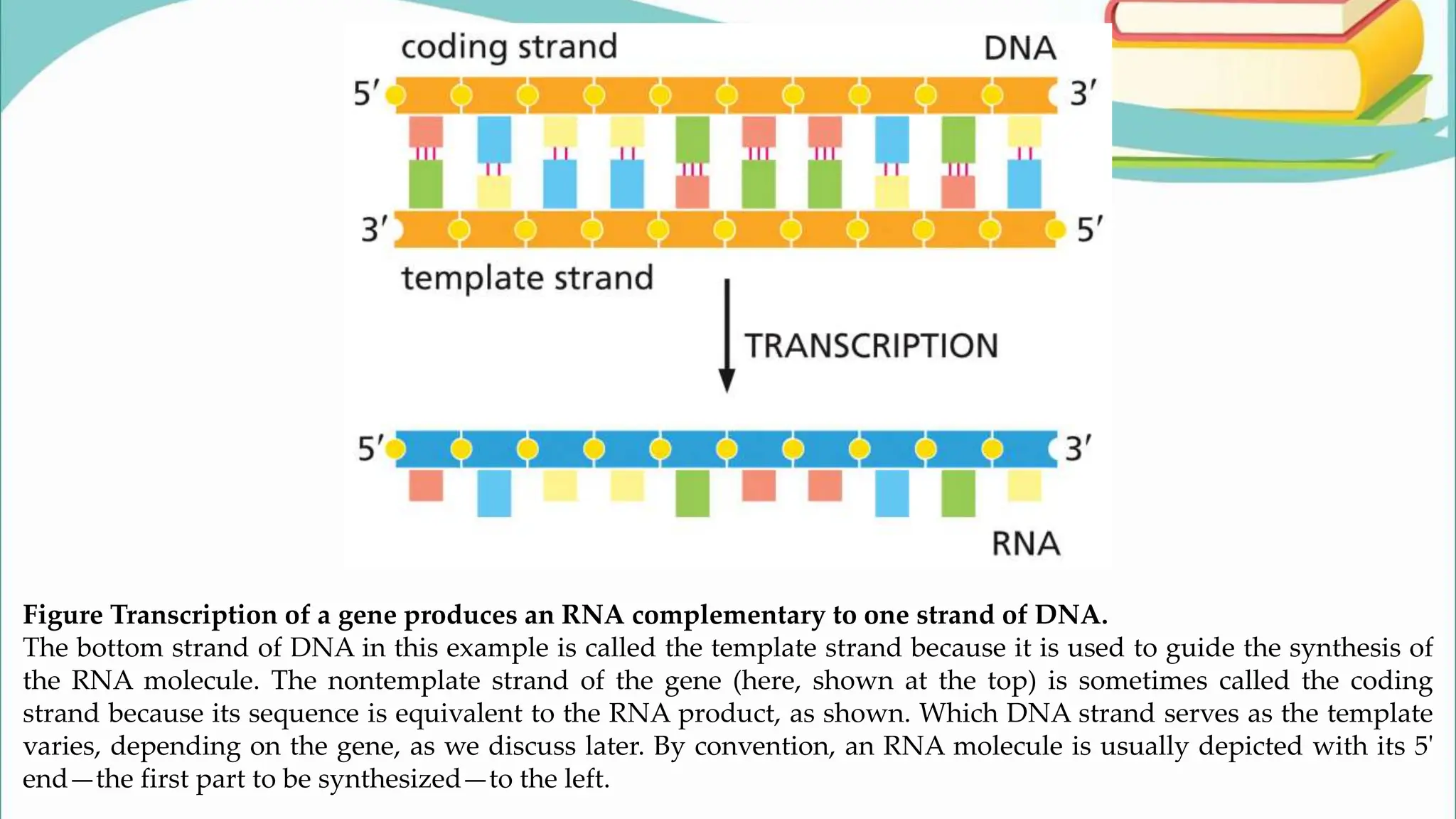

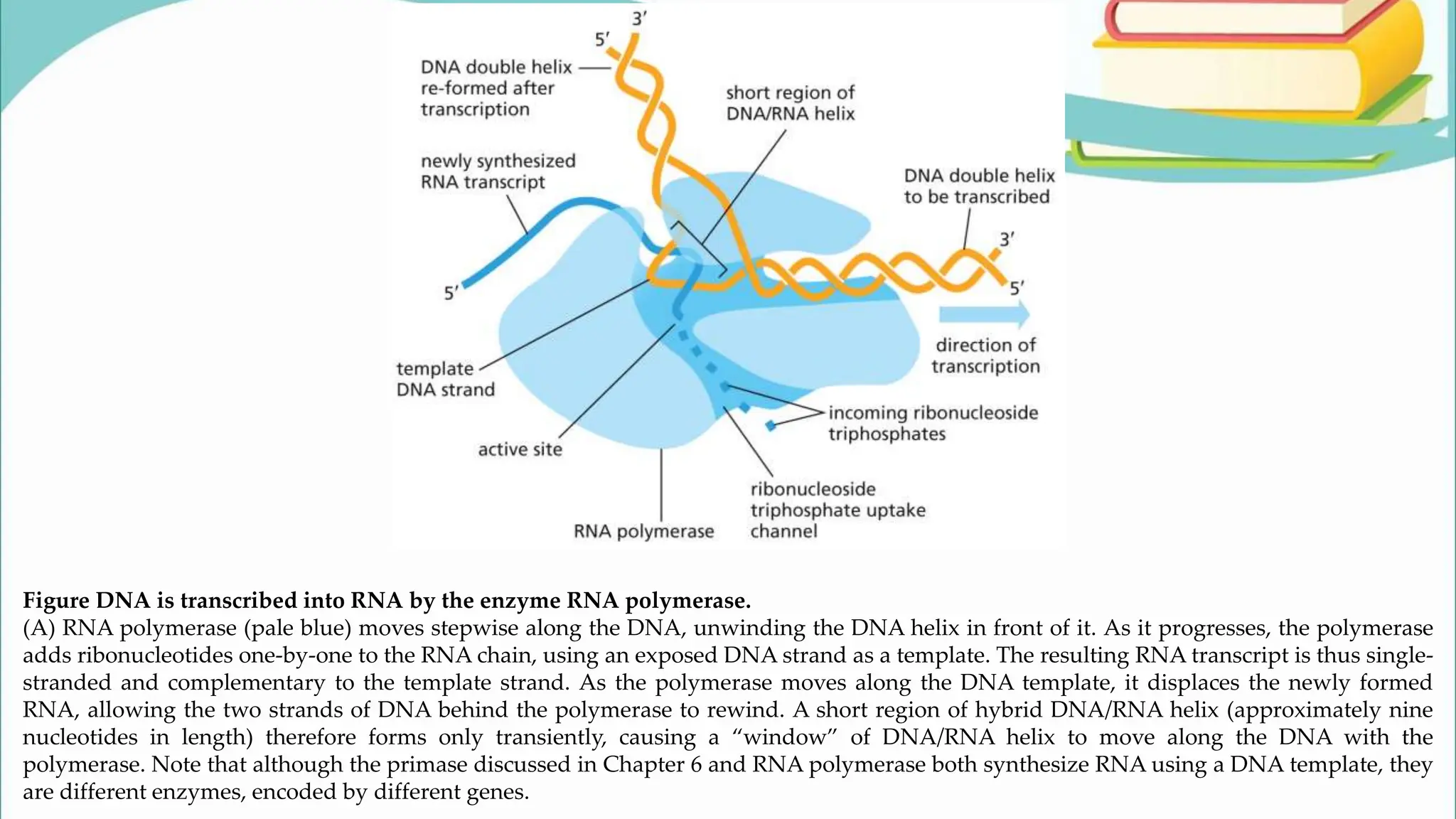

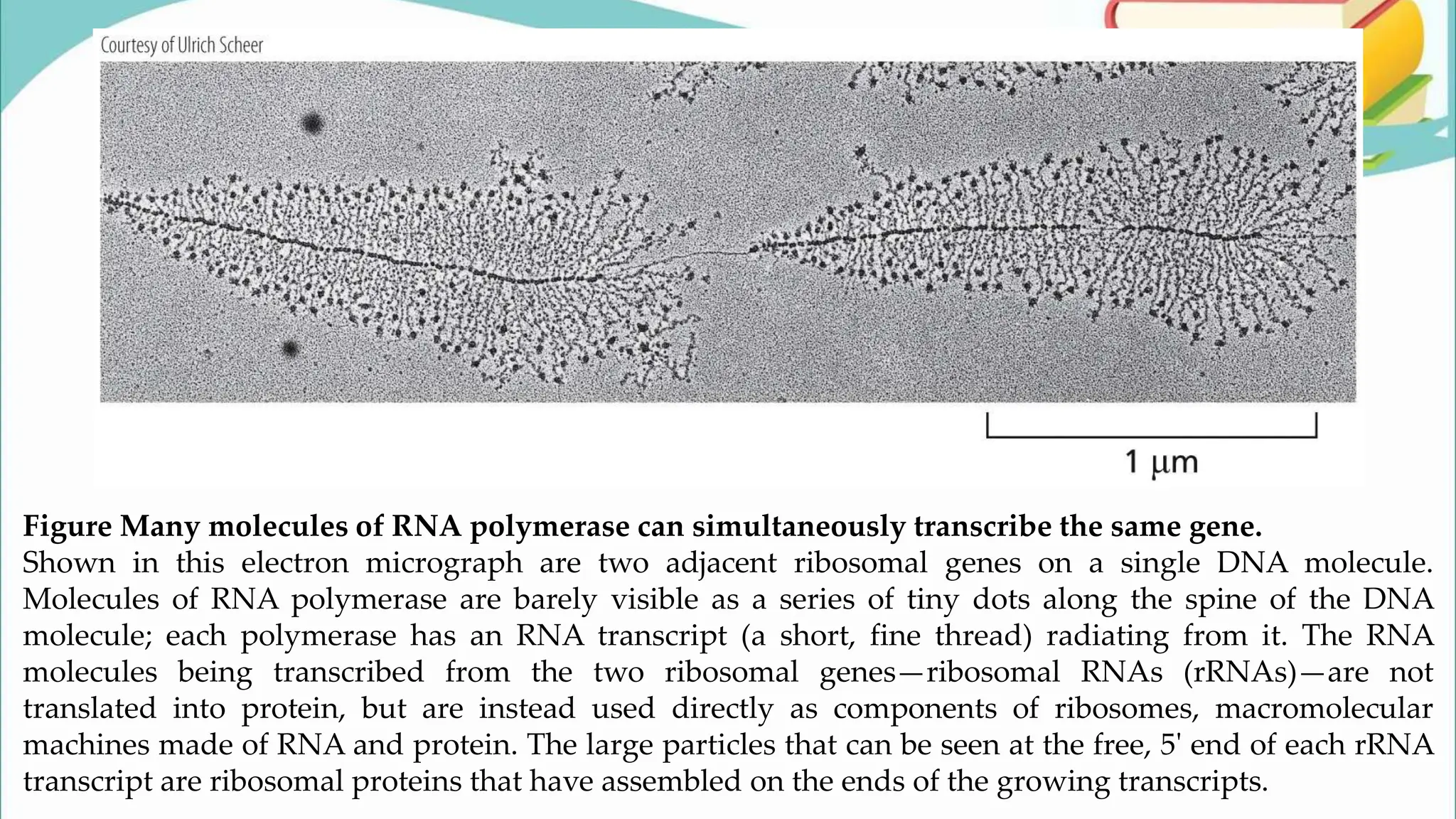

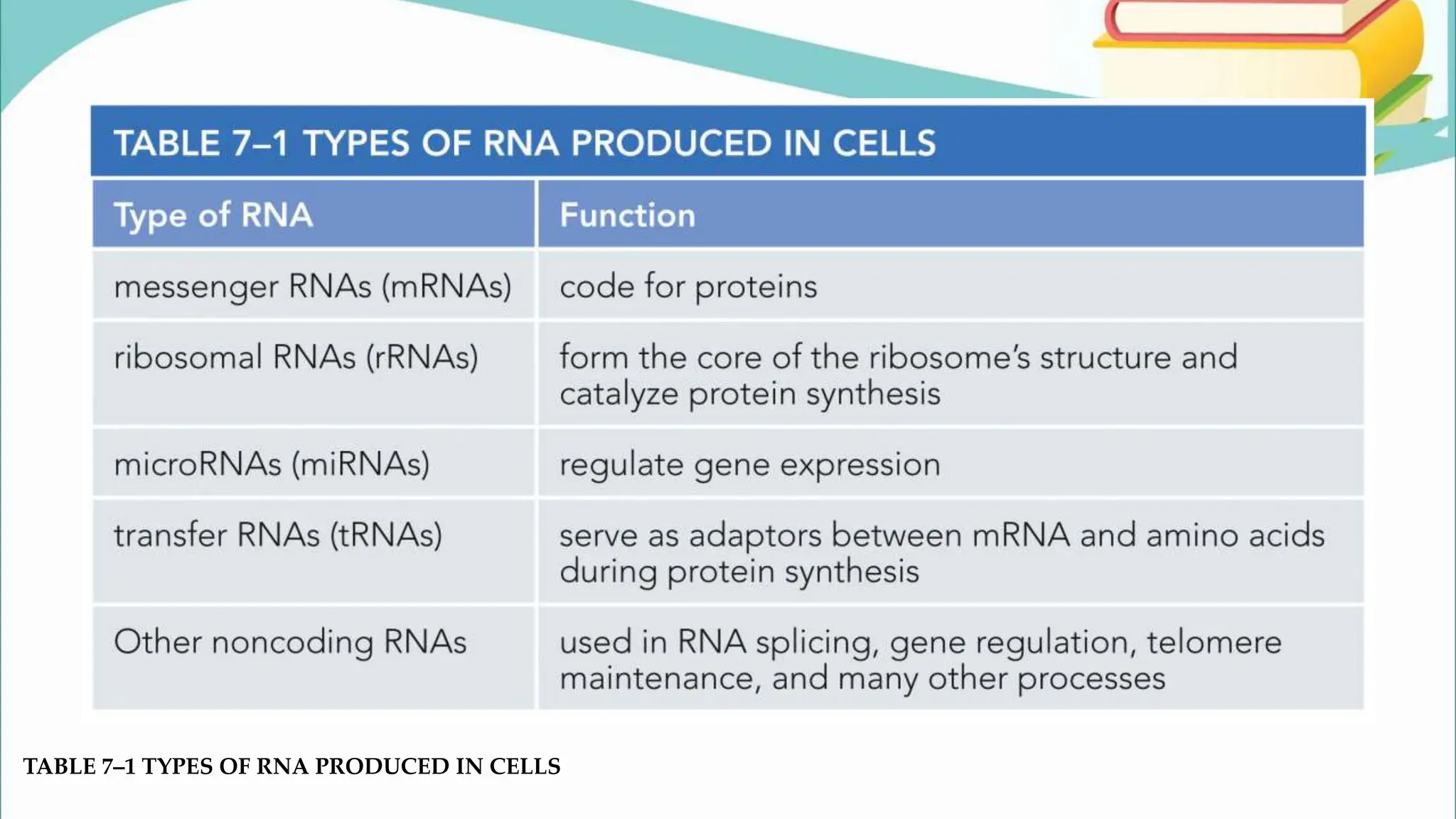

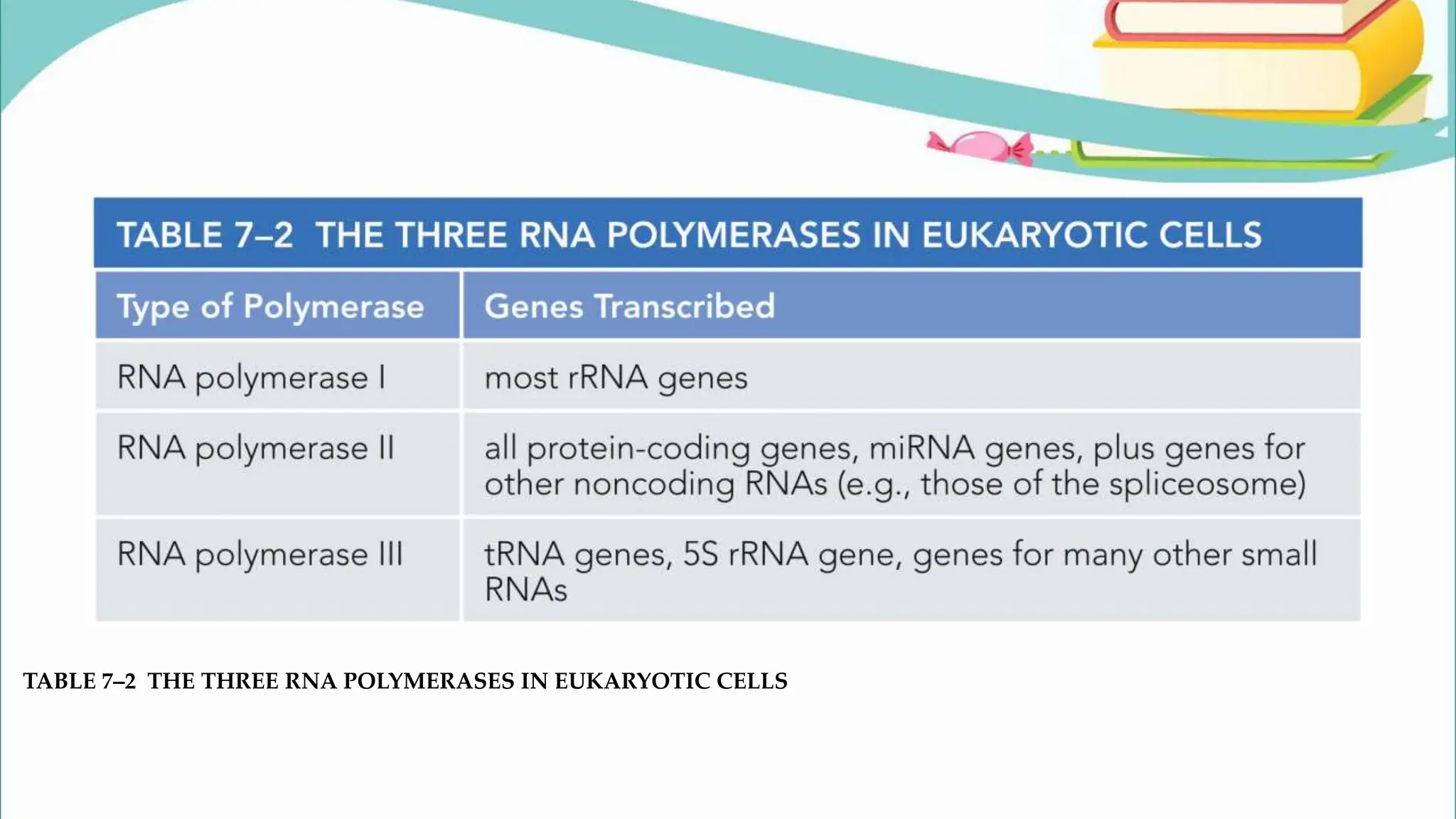

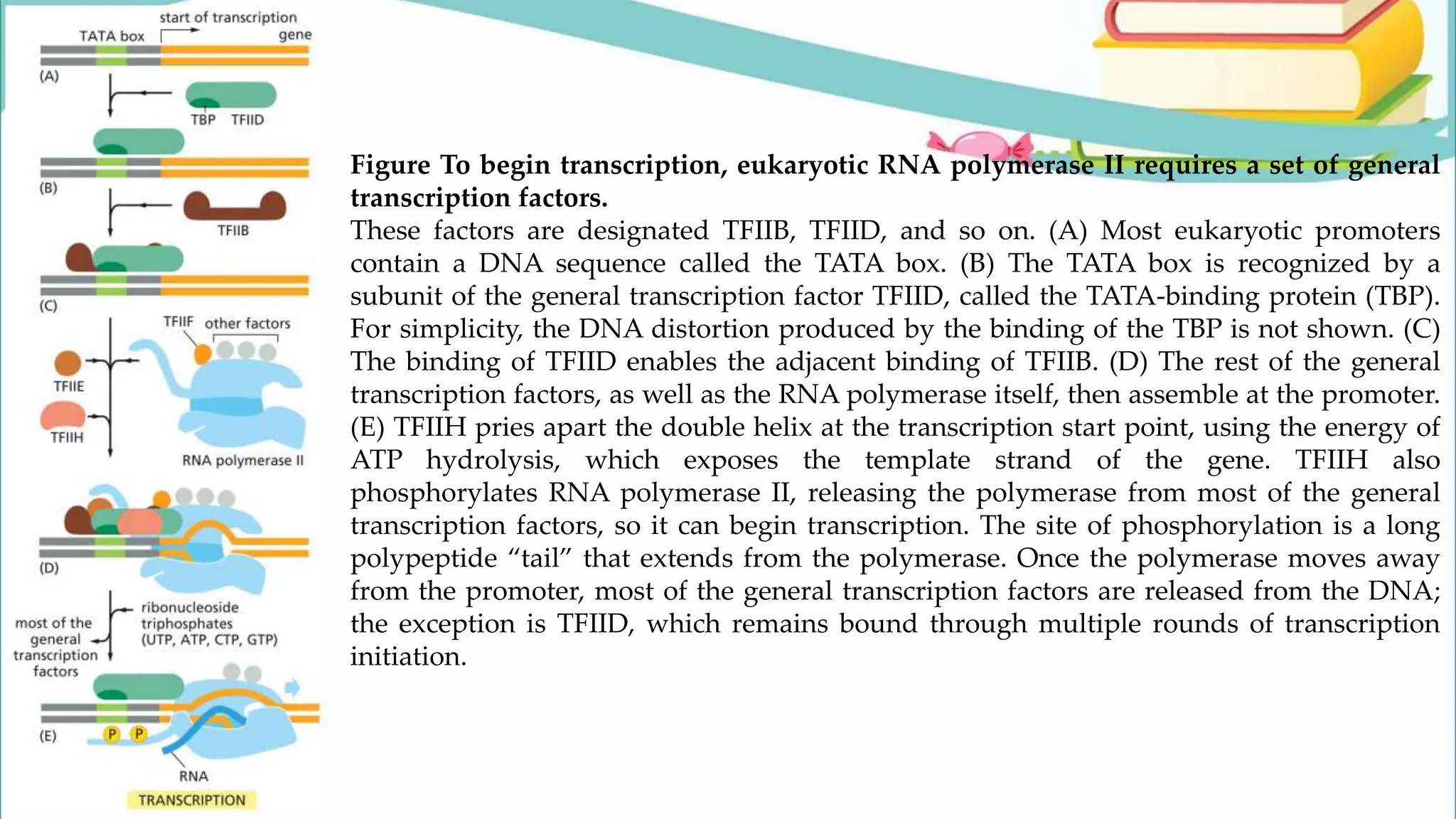

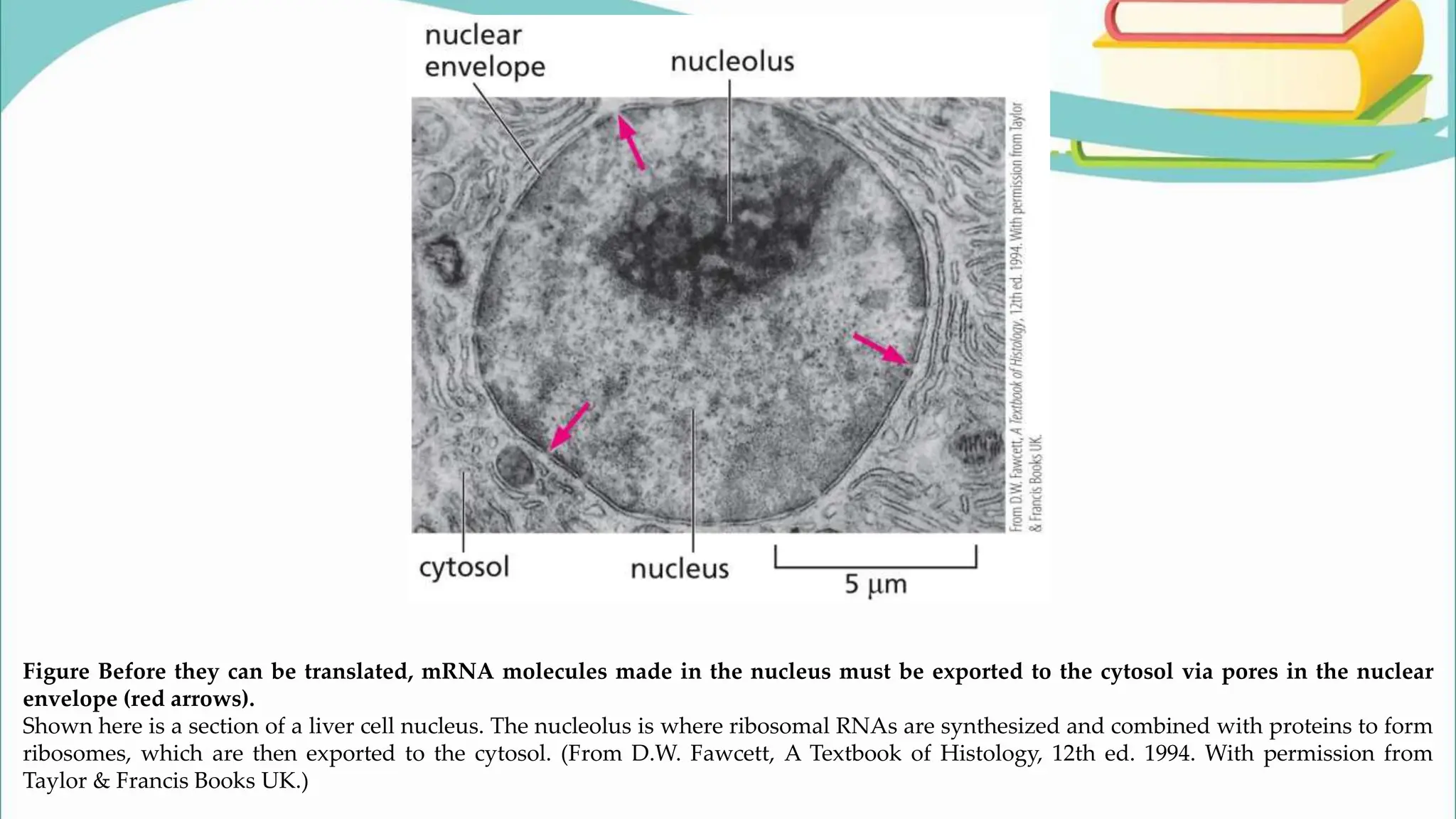

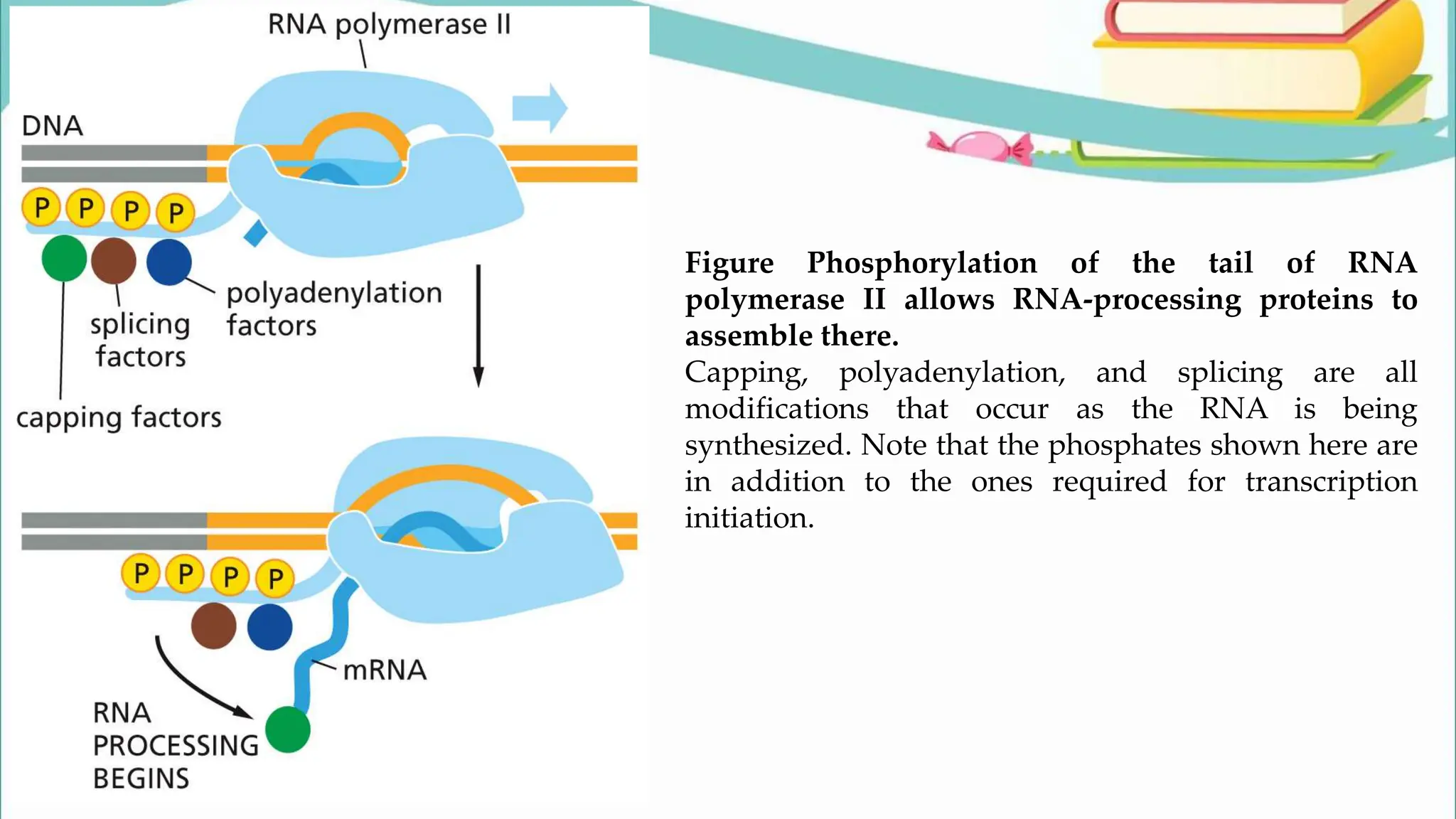

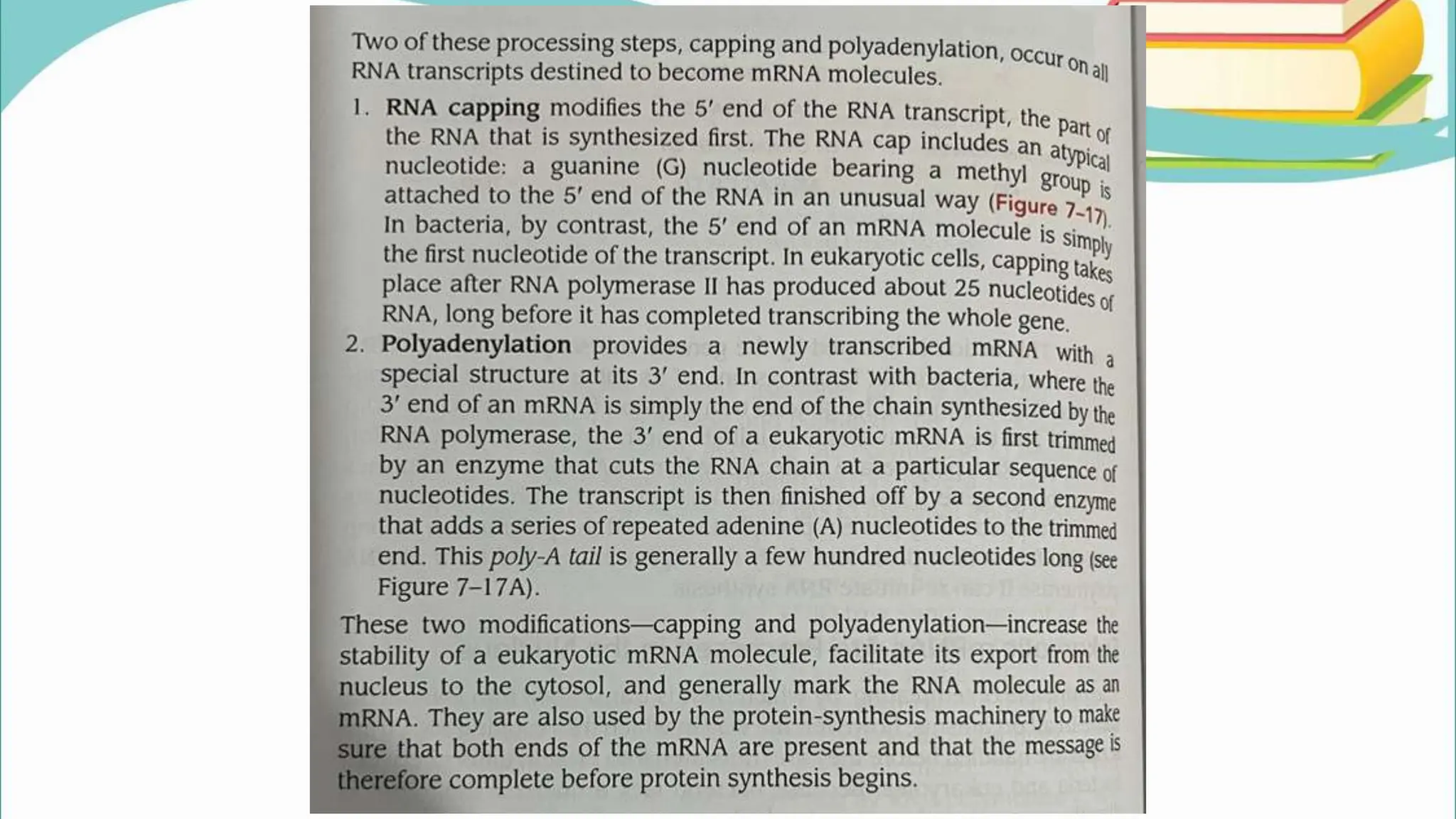

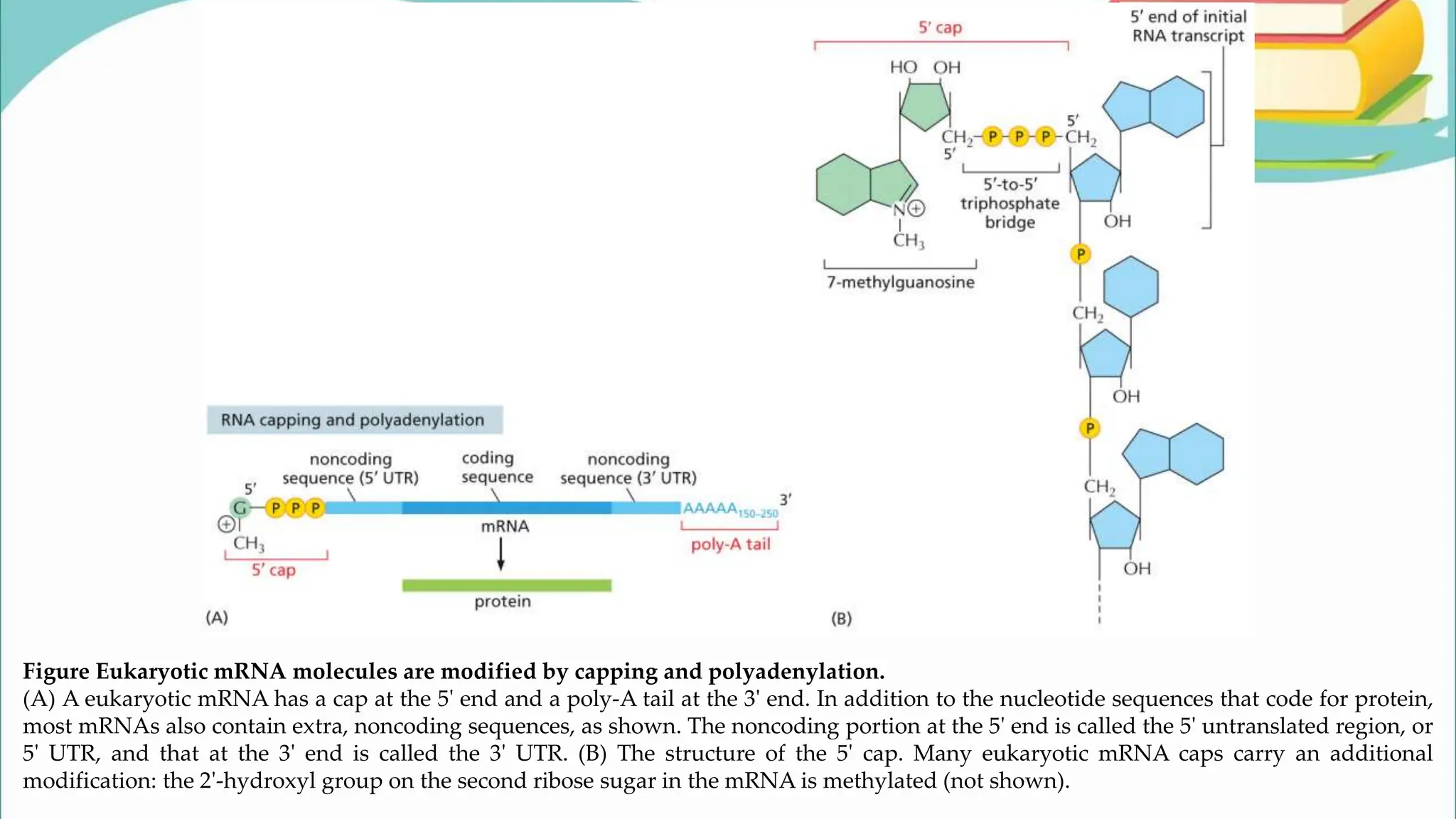

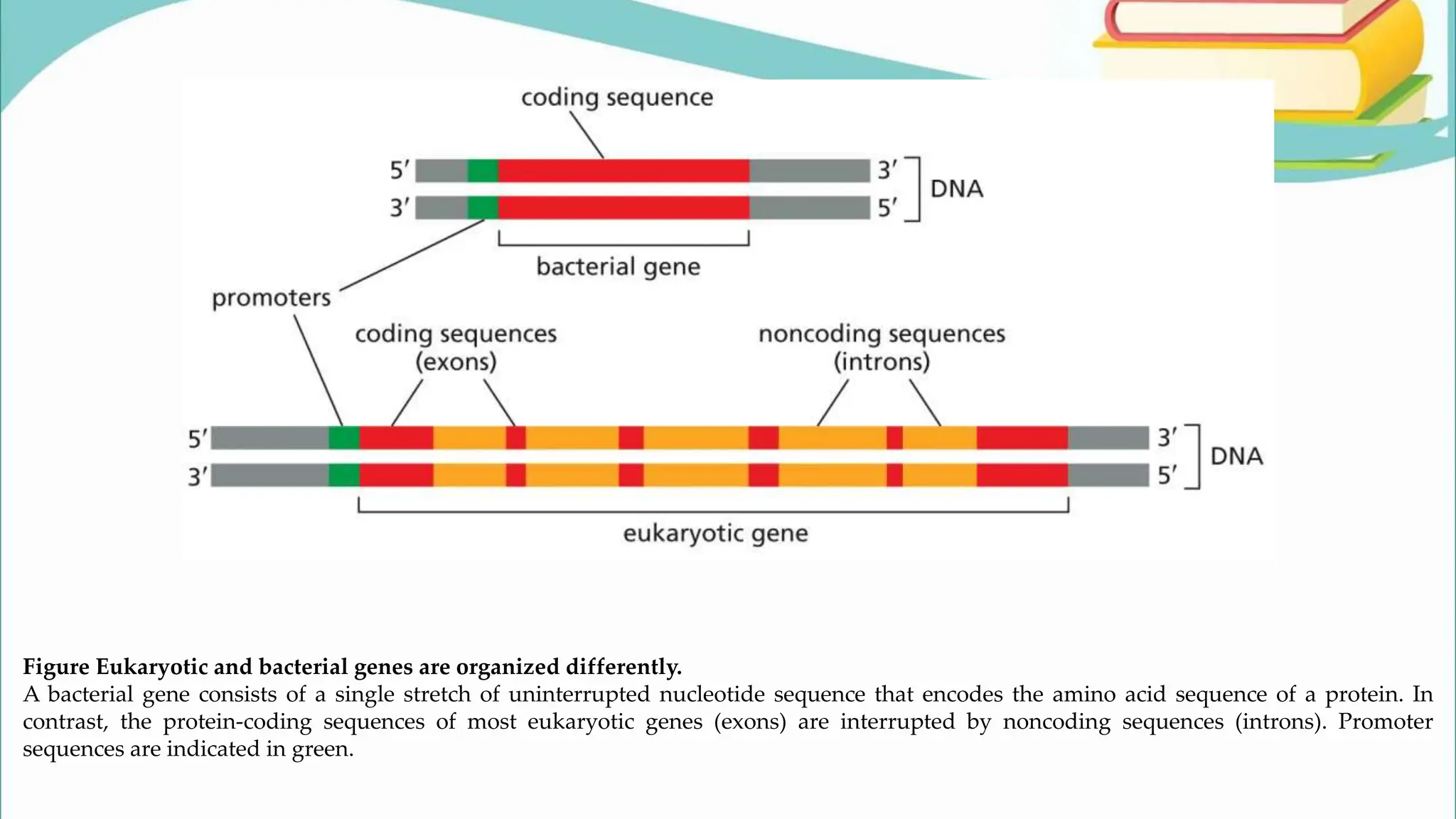

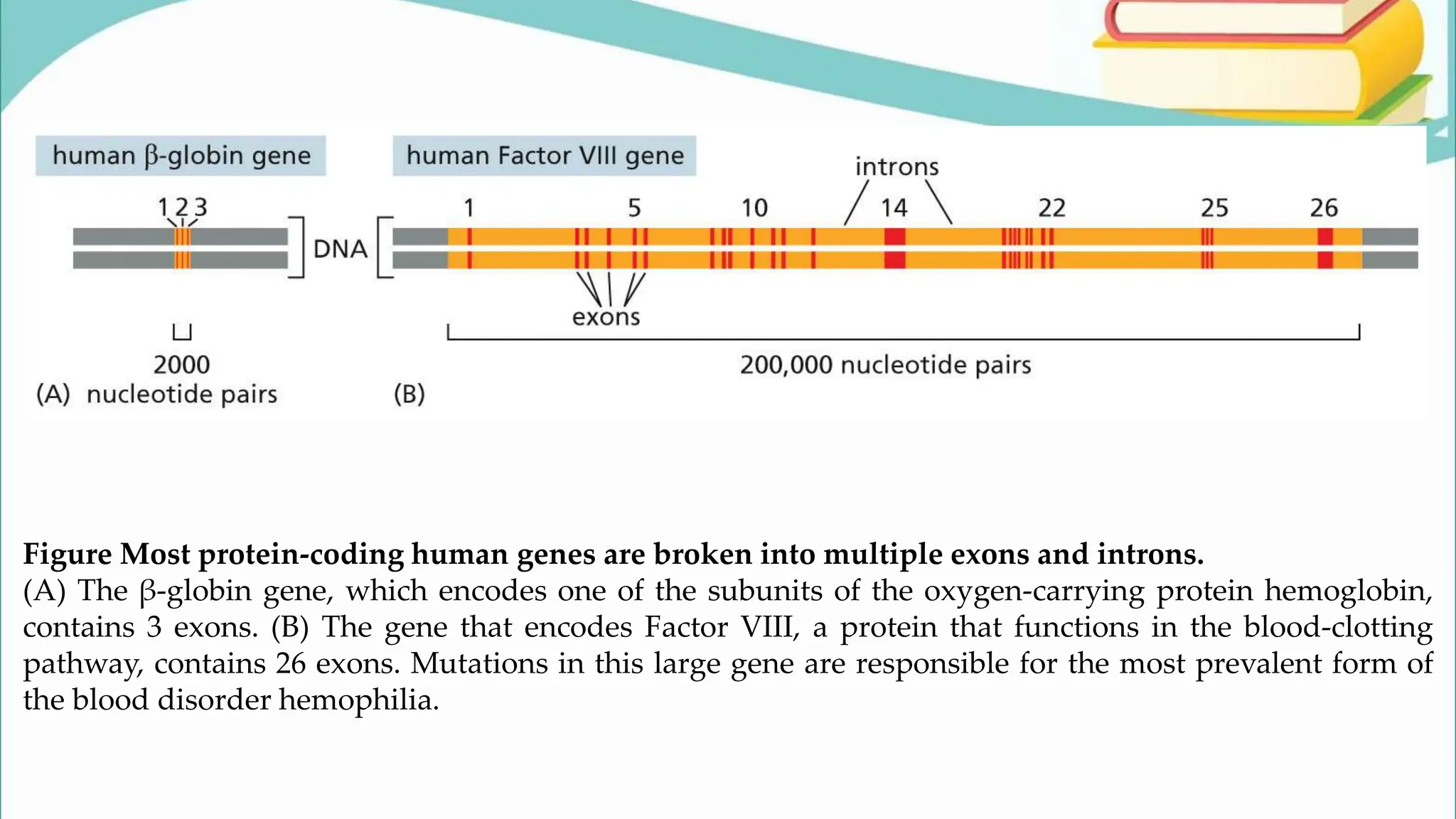

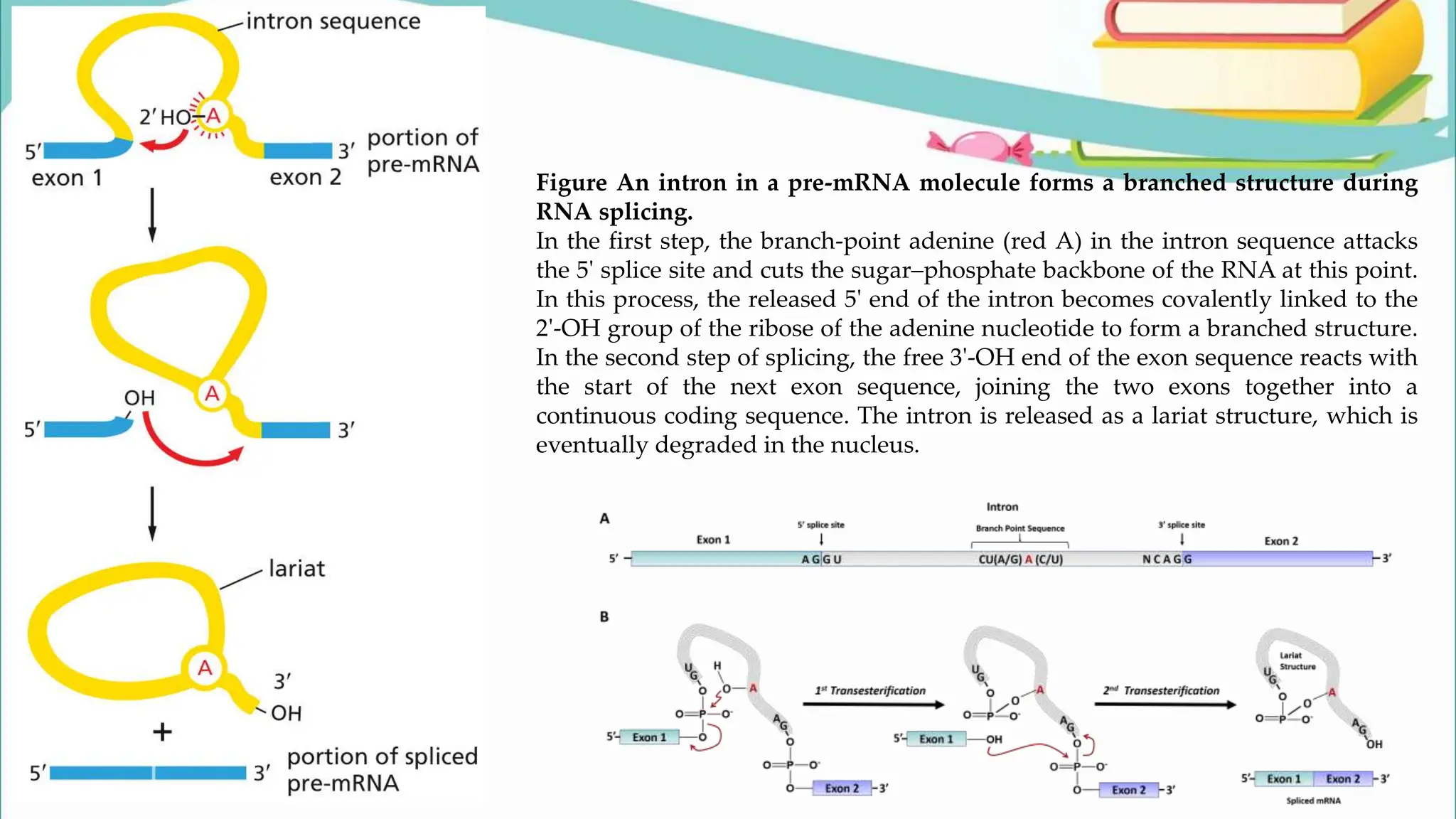

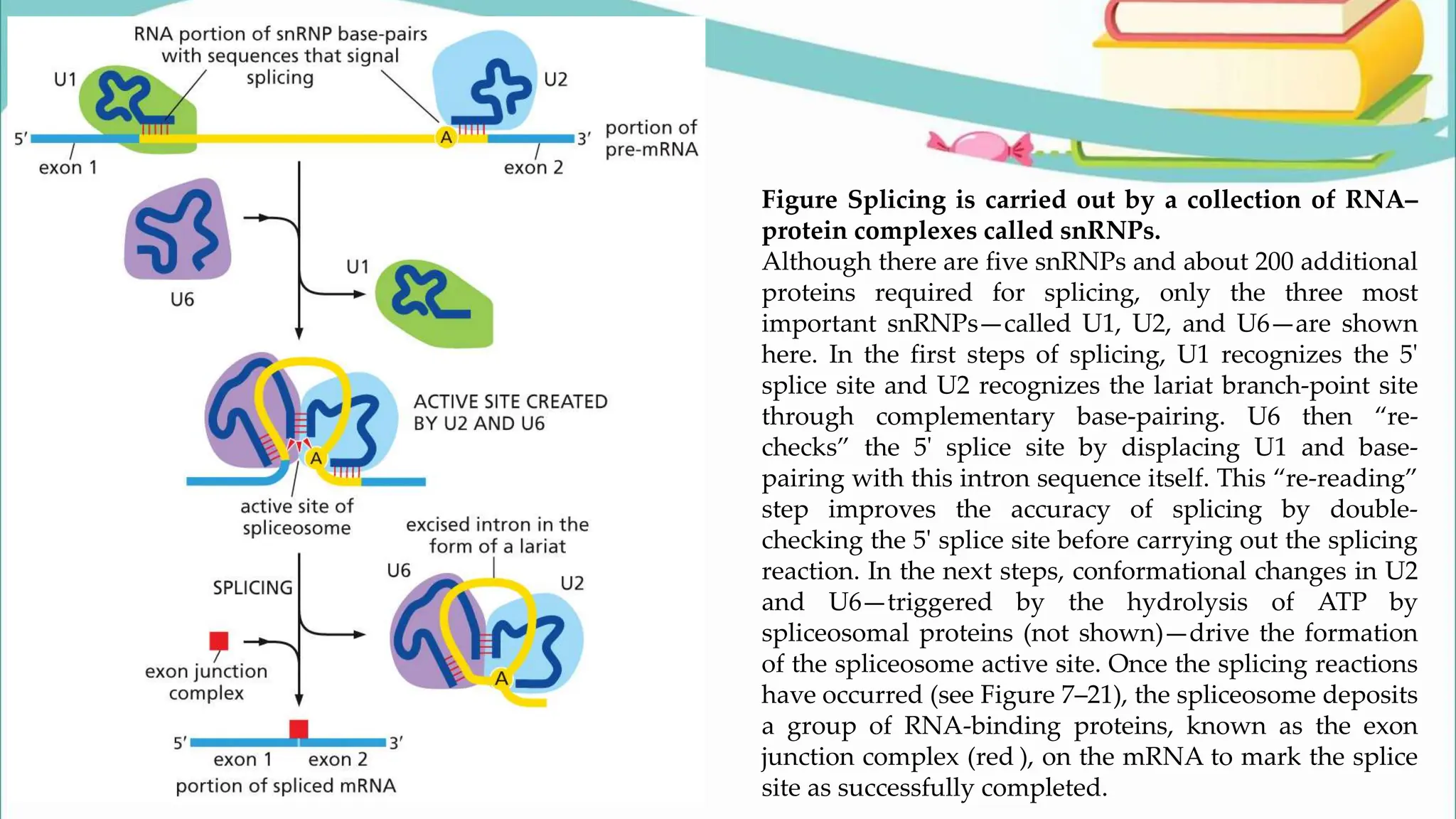

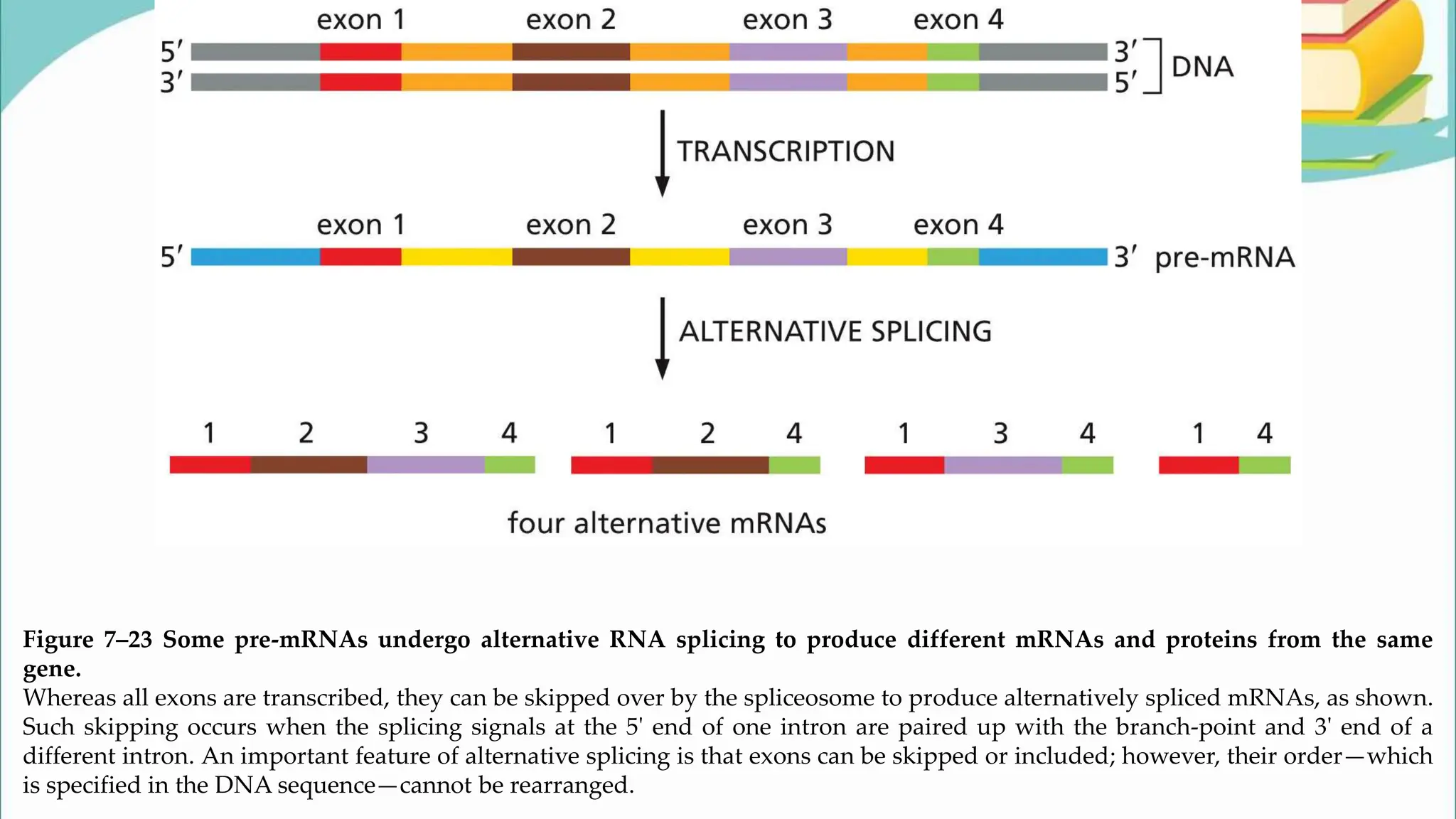

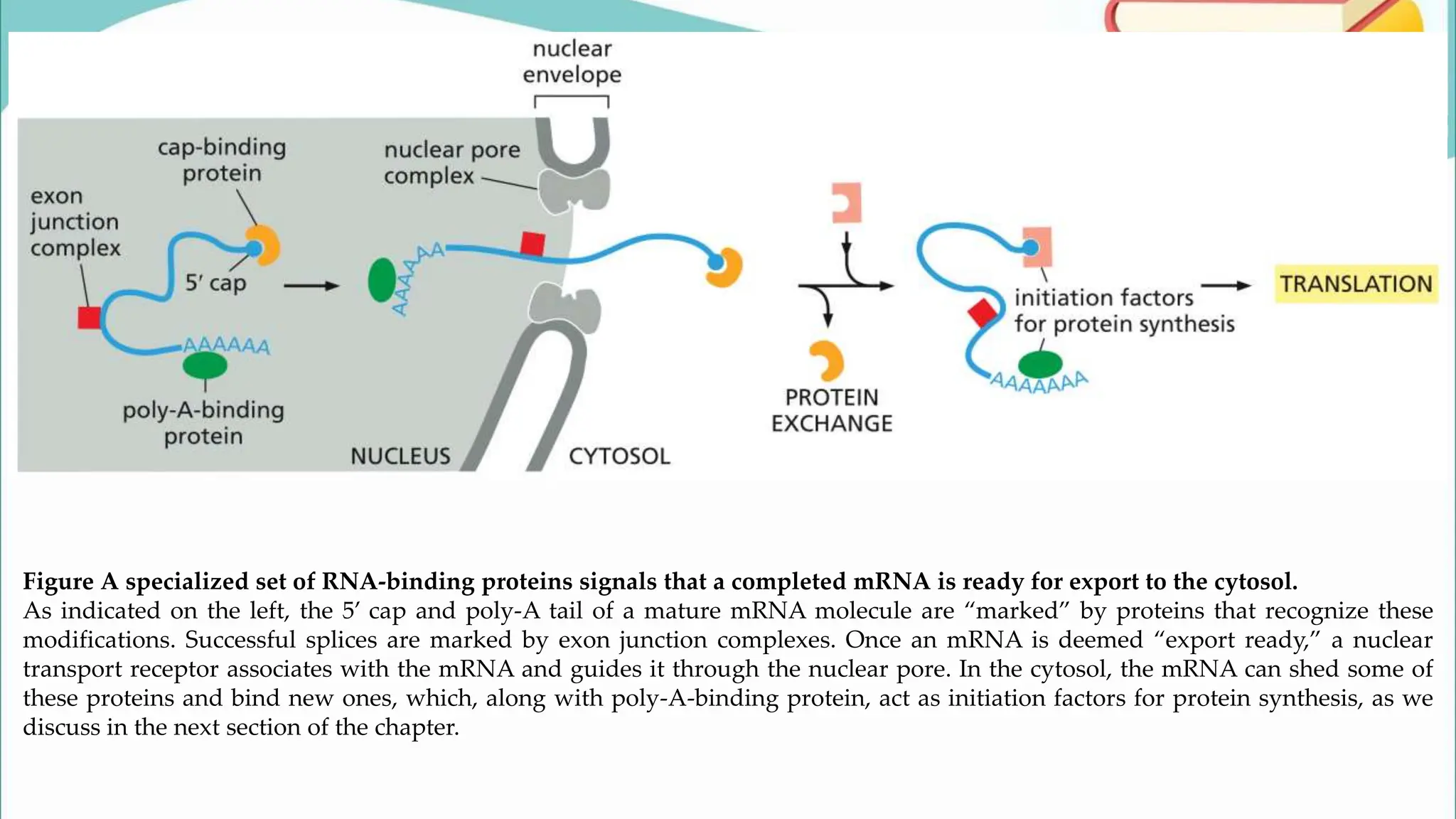

The document discusses the process of transcription in cells, detailing how genetic information flows from DNA to RNA and then to protein synthesis. It outlines the roles of RNA polymerase in transcribing DNA and the various modifications that pre-mRNA undergoes, such as capping, polyadenylation, and splicing, which are essential for producing mature mRNA. Additionally, the document highlights the differences in gene organization between prokaryotes and eukaryotes, emphasizing the complexity of RNA processing in eukaryotic cells.