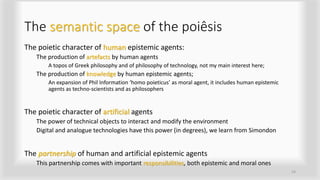

This document discusses the production of knowledge in technological and scientific practices. It argues that knowledge is generated through a partnership between human and artificial agents, rather than being solely the product of human thinkers. Technologies play an essential role in knowledge production by augmenting human capacities, analyzing large amounts of data, and interacting with their environments. This challenges received views that see knowledge as only propositional statements or instruments as merely tools for humans. The document proposes a new framework of "poiêsis" to understand how human and artificial agents co-produce knowledge through their activities. It calls for bringing together different fields like philosophy of science, philosophy of technology, and science and technology studies to study this phenomenon of techno-scientific knowledge production.