Diversity is the new “normal”

✤ Inclusive practices must be dynamic and collaborative

✤ To be truly inclusive, educators must always check for the presence,

participation, and achievement of their learners.

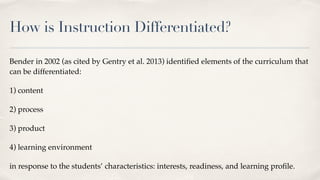

✤ Differentiation plays an important role in the success of inclusive education

practices.