- This document presents the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Thyroid Carcinoma.

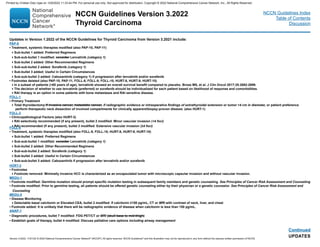

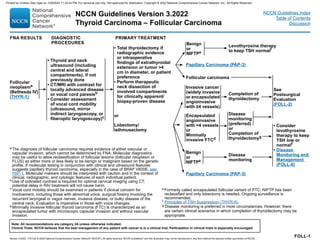

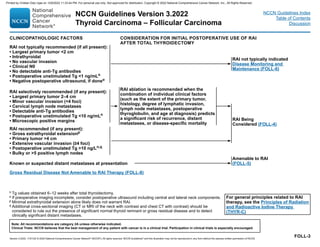

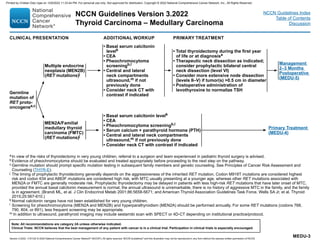

- Version 3.2022 was published on November 1st, 2022 and includes updates to systemic therapy recommendations for papillary, follicular, and Hürthle cell carcinomas.

- The guidelines provide evidence-based recommendations for the evaluation, diagnosis and treatment of the main types of thyroid carcinoma.

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Papillary Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

PAP‑8

• Rising or newly elevated Tg and

negative imaging

• Non‑resectable tumors

• Non‑radioiodine responsivez

Suppress TSH with levothyroxinej

Locoregional

recurrence

Surgery (preferred) if resectablebb

and

Consider Radioiodine treatment,aa if postoperative radioiodine imaging positive

or

Disease monitoring for non‑progressive disease that is stable and distant from

critical structures

or

For select patients with unresectable, non–radioiodine‑avid, and progressive disease,

consider:

EBRT (IMRT/stereotactic body radiation therapy [SBRT])n

and/or

Systemic therapies (Treatment of Metastatic Disease PAP‑9)

or

For select patients with limited burden nodal disease, consider local therapies when

available (ethanol ablation, radiofrequency ablation [RFA])

Metastatic disease

RAI therapy for iodine-avid diseasen

and/or

Local therapies when availablecc

and/or

If not amenable to RAI (Treatment of Metastatic Disease PAP‑9)

RECURRENT DISEASE

Continue surveillance with

unstimulated Tg,

ultrasound, and other imaging as

clinically indicated (PAP‑7)

• Progressively rising Tg (basal or stimulated)

• Scans (including PET) negative

Consider radioiodine therapy with ≥100 mCiaa

and

Post‑treatment iodine-131 imaging (category 3); additional RAI treatments should be

limited to patients who responded to previous RAI therapy (minimum of 6–12 months

between RAI treatments)

Consider preoperative

iodine total body scan

aa

The administered activity of RAI therapy should be adjusted

for pediatric patients. Principles of Radiation and RAI

Therapy (THYR-C).

bb Preoperative vocal cord assessment, if central neck

recurrence.

cc Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

j Principles of TSH Suppression (THYR‑A).

n Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

z

Generally, a tumor is considered iodine‑responsive if follow‑up iodine-123 or low‑dose iodine-131 (1–3

mCi) whole body diagnostic imaging done 6–12 mo after iodine-131 treatment is negative or shows

decreasing uptake compared to pre‑treatment scans. It is recommended to use the same preparation

and imaging method used for the pre‑treatment scan and therapy. Favorable response to iodine-131

treatment is additionally assessed through change in volume of known iodine‑concentrated lesions by

CT/MRI, and by decreasing unstimulated or stimulated Tg levels.

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-17-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Papillary Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

PAP‑9

CNS metastases

(PAP‑11)

TREATMENT OF LOCALLY RECURRENT, ADVANCED, AND/OR METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPY

j Principles of TSH Suppression (THYR‑A).

n Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

cc Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

dd

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly

progressive indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

ee

Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib,

everolimus, pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or

dabrafenib [BRAF positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical

trials are not available or appropriate.

ff

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although most

studies were small and underpowered.

Structurally

persistent/recurrent

locoregional or

distant metastatic

disease not

amenable to RAI

therapy

Bone

metastases

(PAP‑10)

Soft tissue

metastases

(eg, lung, liver,

muscle) excluding

central nervous

system (CNS)

metastases (see

below)

• Continue to

suppress TSH with

levothyroxinej

• For advanced,

progressive, or

threatening disease,

genomic testing to

identify actionable

mutations (including

ALK, NTRK, and

RET gene fusions),

DNA mismatch

repair (dMMR),

microsatellite

instability (MSI), and

tumor mutational

burden (TMB)

• Consider clinical trial

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic

disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)dd

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1)dd

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib (category 1) if progression after lenvatinib and/

or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene

fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion

positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with tumor mutational burden-

high (TMB-H) (≥10 mutations/megabase [mut/Mb]) tumors

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation

that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for

progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or

other systemic therapies are not available or appropriateee,ff

• Consider resection of distant metastases and/or EBRT (SBRT/

IMRTn/other local therapiescc when available to metastatic

lesions if progressive and/or symptomatic (Locoregional disease

PAP‑8)

• Disease monitoring is often appropriate in asymptomatic patients

with indolent disease assuming no brain metastasisdd (PAP‑7)

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

Unresectable

locoregional

recurrent/

persistent disease

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-18-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Papillary Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

PAP‑10

• Consider surgical palliation and/or EBRT/SBRT/other local therapiescc when available if symptomatic, or asymptomatic in

weight‑bearing sites. Embolization prior to surgical resection of bone metastases should be considered to reduce the risk of

hemorrhage

• Consider embolization or other interventional procedures as alternatives to surgical resection/EBRT/IMRT in select cases

• Consider intravenous bisphosphonate or denosumabhh

• Disease monitoring may be appropriate in asymptomatic patients with indolent diseasedd (PAP‑7)

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)dd

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1)dd

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib (category 1) if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab or patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or other

systemic therapies are not available or appropriatedd,ee,ff

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

Bone

metastases

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYgg

ccEthanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

dd Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly progressive

indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

ee

Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib, everolimus,

pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or dabrafenib [BRAF positive]

[all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical trials are not available or appropriate.

ff Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although most studies were

small and underpowered.

gg

RAI therapy is an option in some patients with bone metastases and RAI-sensitive disease.

hh

Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe hypocalcemia;

patients with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at increased risk of

hypocalcemia. Discontinuing denosumab can cause rebound atypical vertebral fractures.

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-19-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Papillary Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

PAP‑11

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYgg

• For solitary CNS lesions, either neurosurgical resection or stereotactic radiosurgeryn is preferred or

• For multiple CNS lesions, consider radiotherapy, including whole brain radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery,n and/or

resection in select cases

and/or

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1) dd,ii,jj

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1) dd,ii,jj

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib (category 1) if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

and/or

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or other

systemic therapies are not available or appropriatedd,ee,ff,hh

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

CNS

metastases

n Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

dd Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly progressive

indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

ee

Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib, everolimus,

pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or dabrafenib [BRAF positive]

[all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical trials are not available or appropriate.

ff Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although most studies were

small and underpowered.

gg

RAI therapy is an option in some patients with bone metastases and RAI-sensitive disease.

hh

Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe hypocalcemia;

patients with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at increased risk of

hypocalcemia. Discontinuing denosumab can cause rebound atypical vertebral fractures.

ii

After consultation with neurosurgery and radiation oncology, data on the efficacy of lenvatinib or

sorafenib for patients with brain metastases have not been established.

jj

Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy should be used with caution in otherwise untreated CNS

metastases due to bleeding risk.

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-20-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Follicular Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

Unresectable

locoregional

recurrent/

persistent disease

CNS metastases

(FOLL‑10)

TREATMENT OF LOCALLY RECURRENT, ADVANCED, AND/OR METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPY

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic

disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)bb

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1)bb

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene

fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion

positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with tumor mutational burden-

high (TMB-H) (≥10 mutations/megabase [mut/Mb]) tumors

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation

that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for

progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or

other systemic therapies are not available or appropriatecc,dd

• Consider resection of distant metastases and/or EBRT (SBRT/

IMRT)i/other local therapiesaa when available to metastatic

lesions if progressive and/or symptomatic. (Locoregional disease

FOLL‑7)

• Disease monitoring is often appropriate in asymptomatic patients

with indolent disease assuming no brain metastasis.dd (FOLL‑6)

• Best supportive care, see the See NCCN Guidelines for Palliative

Care

f See Principles of TSH Suppression (THYR‑A).

i See Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

aa Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

bb

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or

slowly progressive indolent disease. See Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy

(THYR‑B).

cc Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib,

everolimus, pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or

dabrafenib [BRAF positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical

trials are not available or appropriate.

dd Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although

most studies were small and underpowered.

FOLL‑8

Structurally

persistent/recurrent

locoregional or

distant metastatic

disease not

amenable to RAI

therapy

Bone metastases

(FOLL‑9)

• Continue to

suppress TSH with

levothyroxinef

• For advanced,

progressive, or

threatening disease,

genomic testing to

identify actionable

mutations

(including ALK,

NTRK, and RET

gene fusions),

dMMR, MSI, and

TMB

• Consider clinical

trial

Soft tissue

metastases (eg,

lung, liver, muscle)

excluding CNS

metastases (see

below)

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-28-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Follicular Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

FOLL‑9

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYee

• Consider surgical palliation and/or EBRT/SBRT/other local therapiesaa when available if symptomatic, or asymptomatic in

weight‑bearing sites. Embolization prior to surgical resection of bone metastases should be considered to reduce the risk of

hemorrhage

• Consider embolization or other interventional procedures as alternatives to surgical resection/EBRT/IMRT in select casesi

• Consider intravenous bisphosphonate or denosumabff

• Disease monitoring may be appropriate in asymptomatic patients with indolent diseasebb (FOLL‑6)

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)bb

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1)bb

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or other

systemic therapies are not available or appropriatebb,cc,dd

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

Bone

metastases

i See Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

aa Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

bb

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or

slowly progressive indolent disease. See Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy

(THYR‑B).

cc

Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib,

everolimus, pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or

dabrafenib [BRAF positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical

trials are not available or appropriate.

dd

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although

most studies were small and underpowered.

ee

RAI therapy is an option in some patients with bone metastases and RAI-

sensitive disease.

ff

Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe

hypocalcemia; patients with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at

increased risk of hypocalcemia. Discontinuing denosumab can cause rebound

atypical vertebral fractures.

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYee

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-29-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Follicular Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

i Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

aa Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

bb

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly

progressive indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

cc

Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib, everolimus,

pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or dabrafenib [BRAF

positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical trials are not available or

appropriate.

dd

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although most studies

were small and underpowered.

ee

RAI therapy is an option in some patients with bone metastases and RAI-sensitive

disease.

ff

Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe

hypocalcemia; patients with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at increased

risk of hypocalcemia. Discontinuing denosumab can cause rebound atypical vertebral

fractures.

gg

After consultation with neurosurgery and radiation oncology; data on the efficacy of

lenvatinib or sorafenib for patients with brain metastases have not been established.

hh TKI therapy should be used with caution in otherwise untreated CNS metastases due to

bleeding risk.

FOLL‑10

CNS

metastases

• For solitary CNS lesions, either neurosurgical resection or stereotactic radiosurgery is preferred

or

• For multiple CNS lesions, consider radiotherapy,i including whole brain radiotherapy or stereotactic radiosurgery,i and/or

resection in select cases

and/or

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)bb,gg,hh

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1) bb,gg,hh

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

and/or

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or

other systemic therapies are not available or appropriatebb,cc,dd,ff

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYee

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-30-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Hürthle Cell Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

HÜRT‑8

Unresectable

locoregional

recurrent/

persistent disease

Soft tissue

metastases

(eg, lung, liver,

muscle) excluding

CNS metastases

(see below)

CNS

metastases

(HÜRT‑10)

TREATMENT OF LOCALLY RECURRENT, ADVANCED, AND/OR METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPY

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic

disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)cc

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1)cc

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene

fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion

positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation

that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for

progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or

other systemic therapies are not available or appropriatedd,ee

• Consider resection of distant metastases and/or EBRT (SBRT/

IMRT)j/other local therapiesbb when available to metastatic

lesions if progressive and/or symptomatic (Locoregional disease,

HÜRT‑7)

• Disease monitoring is often appropriate in asymptomatic patients

with indolent disease assuming no brain metastasiscc (HÜRT‑6)

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

f Principles of TSH Suppression (THYR‑A).

j Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

bb Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

cc

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be approriate for patients with stable or slowly

progressive indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

dd

Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib,

everolimus, pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or

dabrafenib [BRAF positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical

trials are not available or appropriate.

ee

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although

most studies were small and underpowered.

Structurally

persistent/

recurrent

locoregional

or distant

metastatic

disease not

amenable to

RAI therapy

Bone metastases

(HÜRT‑9)

• Continue to

suppress

TSH with

levothyroxinef

• For advanced,

progressive,

or threatening

disease, genomic

testing to identify

actionable

mutations

(including ALK,

NTRK, and RET

gene fusions),

dMMR, MSI, and

TMB

• Consider clinical

trial

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-38-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Hürthle Cell Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

• Consider surgical palliation and/or EBRT/SBRT/other local therapiesbb when available if symptomatic, or asymptomatic in

weight‑bearing sites. Embolization prior to surgical resection of bone metastases should be considered to reduce the risk of

hemorrhage

• Consider embolization or other interventional procedures as alternatives to surgical resection/EBRT/IMRT in select casesj

• Consider intravenous bisphosphonate or denosumabgg

• Disease monitoring may be appropriate in asymptomatic patients with indolent diseaseee (HÜRT‑6)

• Consider systemic therapy for progressive and/or symptomatic disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)cc

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Sorafenib (category 1)cc

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or other

systemic therapies are not available or appropriatecc,dd,ee

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

Bone

metastases

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYff

HÜRT‑9

j Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

bb Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

cc

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly

progressive indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

dd Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib,

everolimus, pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or

dabrafenib [BRAF positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical

trials are not available or appropriate.

ee

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although

most studies were small and underpowered.

ff

RAI therapy is an option in some patients with bone metastases and RAI-sensitive

disease.

gg

Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe

hypocalcemia; patients with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at

increased risk of hypocalcemia. Discontinuing denosumab can cause rebound

atypical vertebral fractures.

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-39-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Hürthle Cell Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

• For solitary CNS lesions, either neurosurgical resection or stereotactic radiosurgeryj is preferred

or

• For multiple CNS lesions, consider radiotherapy,j including whole brain radiotherapyj or stereotactic radiosurgery,j and/or

resection in select cases

• Consider systemic therapy For progressive and/or symptomatic disease

Preferred Regimens

◊ Lenvatinib (category 1)cc,hh,ii

Other

◊ Sorafenib (category 1) cc,hh,ii

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Cabozantinib if progression after lenvatinib and/or sorafenib

◊ Larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive advanced solid tumors

◊ Selpercatinib or pralsetinib for patients with RET-fusion positive tumors

◊ Pembrolizumab for patients with TMB-H (≥10 mut/Mb) tumors

and/or

◊ Dabrafenib/trametinib for patients with BRAF V600E mutation that has progressed following prior treatment with no

satisfactory alternative treatment options

◊ Other therapies are available and can be considered for progressive and/or symptomatic disease if clinical trials or other

systemic therapies are not available or appropriatecc,dd,ee,gg

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

CNS

metastases

TREATMENT OF METASTATIC DISEASE NOT AMENABLE TO RAI THERAPYdd

j Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

bb Ethanol ablation, cryoablation, RFA, etc.

cc

Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly

progressive indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy (THYR‑B).

dd Commercially available small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as axitinib,

everolimus, pazopanib, sunitinib, vandetanib, vemurafenib [BRAF positive], or

dabrafenib [BRAF positive] [all are category 2A]) can be considered if clinical

trials are not available or appropriate.

ee

Cytotoxic chemotherapy has been shown to have minimal efficacy, although

most studies were small and underpowered.

gg

Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe

hypocalcemia; patients with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at

increased risk of hypocalcemia. Discontinuing denosumab can cause rebound

atypical vertebral fractures.

hh

After consultation with neurosurgery and radiation oncology; data on the efficacy

of lenvatinib or sorafenib for patients with brain metastases have not been

established.

ii

TKI therapy should be used with caution in otherwise untreated CNS metastases

due to bleeding risk.

HÜRT‑10

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-40-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Medullary Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

MEDU‑6

RECURRENT OR PERSISTENT

LOCOREGIONAL DISEASE

Locoregional

Recurrent or

Persistent Disease;

Distant Metastases

(MEDU‑7)

s Increasing tumor markers, in the absence of structural disease progression, are not an indication for treatment with systemic therapy.

t Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly progressive indolent disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy in Advanced

Thyroid Carcinoma (THYR‑B).

u Treatment with systemic therapy is not recommended for increasing calcitonin/CEA alone.

v Only health care professionals and pharmacies certified through the vandetanib Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, a restricted distribution

program, will be able to prescribe and dispense the drug.

w Genomic testing including TMB or RET somatic genotyping in patients who are germline wild-type or germline unknown.

TREATMENT

• Surgical resection is the preferred treatment modality

• EBRT/IMRT can be considered for unresectable disease

or, less commonly, after surgical resection

• Consider systemic therapys for unresectable disease

that is symptomatic or progressing by RECIST criteriat,u

Preferred Regimens

◊ Vandetanibv (category 1)

◊ Cabozantinib (category 1)

◊ Selpercatinib (RET mutation-positive)w

◊ Pralsetinib (RET mutation-positive)w

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Pembrolizumab (TMB-H [≥10 mut/Mb])w

• Disease monitoring

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-46-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Medullary Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

MEDU‑7

RECURRENT OR PERSISTENT DISEASE

DISTANT METASTASES

Asymptomatic

disease

Symptomatic disease

or

Progressiont

• Systemic therapy or clinical trial

Preferred Regimens

◊ Vandetanib (category 1)x

◊ Cabozantinib (category 1)x

◊ Selpercatinib (RET mutation-positive)w

◊ Pralsetinib (RET mutation-positive)w

Other Recommended Regimens

◊ Consider other small‑molecule kinase inhibitorsy

◊ Dacarbazine (DTIC)‑based chemotherapyz

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Pembrolizumab (TMB-H [≥10 mut/Mb])w

• EBRT/IMRT for local symptoms

• Consider intravenous bisphosphonate or denosumabaa therapy for bone

metastases

• Consider palliative resection, ablation (eg, RFA, embolization,

other regional therapy), or other regional treatment

• Best supportive care, see the NCCN Guidelines for Palliative Care

Progressive disease,

see pathway below

sIncreasing tumor markers, in the absence of structural disease progression, are not an indication for

treatment with systemic therapy.

t Kinase inhibitor therapy may not be appropriate for patients with stable or slowly progressive indolent

disease. Principles of Kinase Inhibitor Therapy in Advanced Thyroid Carcinoma (THYR‑B).

uTreatment with systemic therapy is not recommended for increasing calcitonin/CEA alone.

v Only health care professionals and pharmacies certified through the vandetanib Risk Evaluation and

Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, a restricted distribution program, will be able to prescribe and

dispense the drug.

wGenomic testing including TMB or RET somatic genotyping in patients who are germline wild-type or

germline unknown.

xClinical benefit can be seen in both sporadic and familial MTC.

y

While not FDA-approved for treatment of medullary thyroid cancer, other commercially available

small‑molecule kinase inhibitors (such as sorafenib, sunitinib, lenvatinib, or pazopanib) can be

considered if clinical trials or preferred systemic therapy options are not available or appropriate, or if

the patient progresses on preferred systemic therapy options.

zDoxorubicin/streptozocin alternating with fluorouracil/dacarbazine or fluorouracil/dacarbazine

alternating with fluorouracil/streptozocin.

aaDenosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe hypocalcemia; patients

with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at increased risk.

• Disease monitoring

• Consider resection (if possible), ablation (eg, RFA, embolization, other

regional therapy)

• Systemic therapys if not resectable and progressing by RECIST criteriat,u

Preferred Regimens

◊ Vandetanibt,v (category 1)

◊ Cabozantinib (category 1)

◊ Selpercatinib (RET mutation-positive)w

◊ Pralsetinib (RET mutation-positive)w

Useful in Certain Circumstances

◊ Pembrolizumab (TMB-H [≥10 mut/Mb])w

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-47-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Anaplastic Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

STAGEd

R0/R1 resectione

achieved (usually

as incidentally

discovered, very

small ATC)

Adjuvant EBRT/IMRTf

with radiosensitizing

chemotherapyg when

clinically appropriate

EBRT/IMRTf with chemotherapyg

when clinically appropriate

or

Consider molecularly targeted

neoadjuvant therapyh for borderline

resectable disease when safe to do so

Surgery can be

reconsidered after

neoadjuvant therapy

depending on

response

Stage IVA or IVBa,c

(locoregional

disease)

Total thyroidectomy

with therapeutic lymph

node dissection

Resectable

Unresectablee

a Consider core or open biopsy if FNA is “suspicious” for ATC or is not definitive. Morphologic diagnosis combined with immunohistochemistry is necessary to exclude

other entities such as poorly differentiated thyroid cancer, medullary thyroid cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, and lymphoma.

c Preoperative evaluations need to be completed as quickly as possible and involve integrated decision-making in a multidisciplinary team and with the patient. Consider

referral to multidisciplinary high‑volume center with expertise in treating ATC.

d Staging (ST‑1).

e Resectability for locoregional disease depends on extent of involved structures, potential morbidity, and mortality associated with resection. In most cases, there is no

indication for a debulking surgery. Staging (ST‑1) for definitions of R0/R1/R2.

f Principles of Radiation and RAI Therapy (THYR-C).

g Adjuvant/Radiosensitizing Chemotherapy Regimens for Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ANAP‑A [1 of 3]).

h Regimens that may be used for neoadjuvant therapy include dabrafenib/trametinib for BRAF V600E mutations; selpercatinib or pralsetinib for RET-fusion positive

tumors; and larotrectinib or entrectinib for patients with NTRK gene fusion-positive tumors.

TREATMENT

Incomplete

(R2 resection)

ANAP‑2

Disease

Monitoring

and Management

(ANAP-3)

EBRT/IMRTf with

chemotherapyg when

clinically appropriate

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-49-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Anaplastic Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

ANAP‑3

b Molecular testing should include BRAF, NTRK, ALK, RET, MSI, dMMR, and tumor mutational burden.

d Staging (ST‑1).

i Consider dabrafenib/trametinib if BRAF V600E mutation positive (Subbiah V, et al. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:7‑13); larotrectinib or entrectinib if NTRK gene fusion positive

(Drilon A, et al. N Engl J Med 2018;378:731‑739; Doebele RC, et al. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:271-282); selpercatinib or pralsetinib if RET fusion positive (Wirth L,

et al. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Society for Medical Oncology in Barcelona, Spain; September 27-October 1, 2019. Oral presentation.); or

pembrolizumab for TMB-H (Marabelle A, et al. Presented at the Annual Meeting of ESMO in Barcelona, Spain; September 30, 2019).

j Consider use of intravenous bisphosphonates or denosumab. Denosumab and intravenous bisphosphonates can be associated with severe hypocalcemia; patients

with hypoparathyroidism and vitamin D deficiency are at increased risk.

k Systemic Therapy Regimens for Metastatic Disease (ANAP-A [2 of 3]).

DISEASE MONITORING AND MANAGEMENT

• Cross‑sectional imaging

(CT or MRI with contrast)

of brain, neck, chest,

abdomen, and pelvis

at frequent intervals as

clinically indicated

• Consider FDG PET/CT 3–6

months after initial therapy

• Continued disease

monitoring if no

evidence of disease

(NED)

• Palliative locoregional

radiation therapy

• Local lesion control (eg,

bone,j brain metastases)

• Second‑line systemic

therapyk or clinical trial

• Best supportive

care, see the NCCN

Guidelines for Palliative

Care

Stage IVCd

Aggressive

therapy

Palliative

care

• Total thyroidectomy with therapeutic

lymph node dissection if resectable

(R0/R1)

• Consider tracheostomy

• Locoregional radiation therapy

• Systemic therapy (See ANAP‑A [2 of 3])

• Molecular testing for actionable

mutationsi if not previously doneb

• Consider clinical trial

• Palliative locoregional radiation

therapy

• Local lesion control with surgery or

radiation (eg, bone,j brain metastases)

• Consider tracheostomy

• NCCN Guidelines for Central Nervous

System Cancers

• Best supportive care

METASTATIC

DISEASE

TREATMENT

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-50-320.jpg)

![Paclitaxel8

60–90 mg/m² IV

or

135–200 mg/m²

Weekly

Every 3–4 weeks

Doxorubicin8

20 mg/m² IV

or

60–75 mg/m² IV

Weekly

Every 3 weeks

Paclitaxel/carboplatin1 (category 2B)

Paclitaxel 60–100 mg/m2

, carboplatin AUC 2 IV

or

Paclitaxel 135–175 mg/m2

, carboplatin AUC 5–6 IV

Weekly

Every 3–4 weeks

Docetaxel/doxorubicin1 (category 2B)

Docetaxel 60 mg/m2

IV, doxorubicin 60 mg/m2

IV (with pegfilgrastim)

or

Docetaxel 20 mg/m2

IV, doxorubicin 20 mg/m2

IV

Every 3–4 weeks

Weekly

Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma – Anaplastic Carcinoma

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

ANAP‑A

2 OF 3

SYSTEMIC THERAPY

Systemic Therapy Regimens for Metastatic Disease

Preferred Regimens

Dabrafenib/trametinib2

(BRAF V600E mutation positive)

Dabrafenib 150 mg PO

and

Trametinib 2 mg PO

Twice daily

Once daily

Larotrectinib3

(NTRK gene fusion positive) 100 mg PO Twice daily

Entrectinib4

(NTRK gene fusion positive) 600 mg PO Once daily

Pralsetinib5

(RET fusion positive) 400 mg PO Once daily

Selpercatinib6

(RET fusion positive)

120 mg PO (50 kg)

or

160 mg PO (≥50 kg)

Twice daily

Other Recommended Regimens

Useful in Certain Circumstances

Doxorubicin/cisplatin8 Doxorubicin 60 mg/m² IV, cisplatin 40 mg/m² IV Every 3 weeks

Pembrolizumab7

(TMB-H [≥10 mut/Mb])

200 mg IV

or

400 mg IV

Every 3 weeks

Every 6 weeks

References

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-52-320.jpg)

![NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma

Version 3.2022, 11/01/22 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network®

(NCCN®

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines®

and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Note: All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Clinical Trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any patient with cancer is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

NCCN Guidelines Index

Table of Contents

Discussion

THYR‑C

2 OF 5

PRINCIPLES OF RADIATION AND RADIOACTIVE IODINE THERAPY

IODINE-131 ADMINISTRATION

Administered Activity

See special circumstances below for pediatric dose adjustment.

• Remnant ablation:

30–50 mCi

◊ If RAI ablation is used in T1b/T2 (1–4 cm), clinical N0 disease, in

the absence of other adverse pathologic, laboratory, or imaging

features, 30–50 mCi of iodine-131 is recommended (category 1)

following either thyrotropin alfa stimulation or thyroid hormone

withdrawal. This dose of 30–50 mCi may also be considered

(category 2B) for patients with T1b/T2 (1–4 cm) with small-

volume N1a disease (fewer than 5 lymph node metastases 2

mm in diameter) and for patients with primary tumors 4 cm,

clinical M0 with minor extrathyroidal extension.4,5

• Adjuvant therapy:

50–150 mCi

◊ For higher likelihood of residual disease based on operative

pathology or pretherapy radioiodine scan

• Treatment of known disease

100–200 mCi

◊ For proven unresectable or metastatic disease based on

pathology or pretherapy radioiodine scan

Dosimetry can be used to determine maximal dose at high-volume

centers for documented nonresectable, large-volume, iodine-

concentrating, residual, or recurrent disease. Generally, the

maximum 48-hour whole-body dose should not exceed ~80 mCi to

avoid pulmonary fibrosis in the case of diffuse lung metastases,

and the bone marrow retention maximum should not exceed ~120

mCi at 48 hours.1

Special Circumstances

• Pediatric patients:

Chest imaging using non-contrast CT prior to treatment to assess

for lung metastases

Weight-based dose adjustment for pediatric patients assuming

routine dosing for 70 kg adult (ie, a 150 mCi dose for a 70 kg adult

would translate to 2.15 mCi/kg for the pediatric patient)6

Special Circumstances

• RAI after imaging study or procedure using iodine contrast agent:

Wait 2 months to allow for free iodine levels to decrease (100

mcg/24 hours) and allow for optimal RAI uptake7,8

Consider measurement of 24-hour urine iodine to confirm a normal

free iodine prior to preparing for dosing.

• Breastfeeding patients:

Wait 3–6 months after cessation of lactation or with normalization

of serum prolactin levels.

Complete cessation of breastfeeding after iodine-123 or iodine-131

administration for the current infant. There should be no increased

risk to mother or infant for breastfeeding with subsequent births

assuming no radioiodine is administered around the subsequent

birth/breastfeeding period.9

• Decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR)/end-stage renal disease

(ESRD)/hemodialysis:

Special consideration to administered dose, and timing with

respect to dialysis to maximize therapeutic effect and minimize

non-thyroid uptake/exposure10

Multidisciplinary involvement including close monitoring by

radiation safety to coordinate administration, monitoring, and

minimization of exposure to others

• Patients desiring pregnancy

Patients should be counseled to wait at least 6 months after

iodine-131 therapy to attempt pregnancy to avoid adverse

pregnancy outcomes (such as fetal hypothyroidism, malformation,

increased malignancy risk in the child, or fetal demise [with

high doses]) related to RAI. For many patients a longer interval

before attempting pregnancy may be recommended to confirm

disease-free status at 6–12 months post-RAI. In these cases,

earlier pregnancy is inadvisable as it would interfere with disease

detection and further management.

In selective cases when doses are high or other considerations

are present, integrating care with reproductive endocrinology/

oncofertility for men and women may be appropriate.

References

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-57-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network©

(NCCN©

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma

MS-5

System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology.61

As of the 2021 update to

the NCCN Guidelines for Thyroid Carcinoma, management

recommendations are no longer provided for nodules classified as

Bethesda I and Bethesda II. Pathology and cytopathology slides should be

reviewed at the treating institution by a pathologist with expertise in the

diagnosis of thyroid disorders. Although FNA is a very sensitive test—

particularly for papillary carcinoma—false-negative results are sometimes

obtained; therefore, a reassuring FNA should not override worrisome

clinical or radiographic findings.62,63

Molecular diagnostic testing to detect individual mutations (eg, BRAF

V600E, RET/PTC, RAS, PAX8/PPAR [peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptor] gamma) or pattern recognition approaches using molecular

classifiers may be useful in the evaluation of FNA samples that are

indeterminate to assist in management decisions.64-72

The BRAF V600E

mutation occurs in about 45% of patients with papillary carcinoma and is

the most common mutation.73

Some studies have linked the BRAF V600E

mutation to poor prognosis, especially when occurring with TERT

promoter mutation.74-77

The choice of the precise molecular test depends

on the cytology and the clinical question being asked.78-81

Indeterminate

groups include: 1) follicular or Hürthle cell neoplasms (Bethesda IV); and

2) AUS/FLUS (Bethesda III).82-84

The NCCN Panel recommends

consideration of molecular diagnostic testing for these indeterminate

groups.85,86

Historically, studies have shown that molecular diagnostics do not perform

well for Hürthle cell neoplasms.83,87,88

More recently, modern genomic

classifiers have shown promise for diagnosis of Hürthle cell-containing

specimens, with sensitivity values ranging from 88.9% to 92.9% and

specificity values ranging from 58.8% to 69.3% for detecting Hürthle cell

cancers.89,90

Molecular diagnostic testing may include multigene assays or

individual mutational analysis. In addition to their utility in diagnostics,

molecular markers are beneficial for making decisions about targeted

therapy options for advanced disease and for informing eligibility for some

clinical trials. In addition, the presence of some mutations may have

prognostic importance.

A minority of panelists expressed concern regarding active nodule

surveillance of follicular lesions because they were perceived as

potentially pre-malignant lesions with a very low, but unknown, malignant

potential if not surgically resected (leading to recommendations for either

nodule surveillance or considering lobectomy in lesions classified as

benign by molecular testing). Clinical risk factors, sonographic patterns,

and patient preference can help determine whether nodule surveillance or

surgery is appropriate for these patients. Guidance regarding nodule

surveillance from the ATA and the ACR TI-RADS should be followed.3,59

A

systematic review including 27 studies that evaluated repeat FNA in

AUS/FLUS nodules showed that 48% (95% CI, 43%–54%) of nodules

were reclassified as benign, with a negative predictive value (NPV) greater

than 96%.91

FNA may be repeated for AUS/FLUS, especially if molecular

diagnostics are technically inadequate.

Rather than proceeding to immediate surgical resection to obtain a

definitive diagnosis for these indeterminate FNA cytology groups (follicular

lesions), patients can be followed with nodule surveillance if the

application of a specific molecular diagnostic test (in conjunction with

clinical and ultrasound features) results in a predicted risk of malignancy

that is comparable to the rate seen in cytologically benign thyroid FNAs

(approximately ≤5%). It is important to note that the predictive value of

molecular diagnostics may be significantly influenced by the pre-test

probability of disease associated with the various FNA cytology groups.

Furthermore, in the cytologically indeterminate groups, the risk of

malignancy from FNA can vary widely between institutions.61,92

Because

the published studies have focused primarily on adult patients with thyroid

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-71-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network©

(NCCN©

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma

MS-8

with thyroid carcinoma—especially those who are older than 40 years—

may be regarded with special concern.121

Familial Syndromes

Familial, non-medullary carcinoma accounts for about 5% of PTCs and, in

some cases, may be clinically more aggressive than the sporadic

form.122,123

For patients to be considered as having familial papillary

carcinoma, most studies require at least three first-degree relatives to be

diagnosed with papillary carcinoma because the finding of cancer in a

single first-degree relative may just be a chance event. Microscopic

familial papillary carcinoma tends to be multifocal and bilateral, often with

vascular invasion, lymph node metastases, and high rates of recurrence

and distant metastases.124

Other familial syndromes associated with

papillary carcinoma are familial adenomatous polyposis,125

Carney

complex (multiple neoplasia and lentiginosis syndrome, which affects

endocrine glands),126

and Cowden syndrome (multiple hamartomas).127

The prognosis for patients with all of these syndromes is not different from

the prognosis of those with spontaneously occurring papillary carcinoma.

Tumor Variables Affecting Prognosis

Some tumor features have a profound influence on prognosis.111,128-130

The

most important features are tumor histology, primary tumor size, local

invasion, necrosis, vascular invasion, BRAF V600E mutation status, and

metastases.74,131,132

For example, vascular invasion (even within the

thyroid gland) is associated with more aggressive disease and with a

higher incidence of recurrence.133-136

The CAP protocol provides

definitions of vascular invasion and other terms (see Protocol for the

Examination of Specimens From Patients With Carcinomas of the Thyroid

Gland on the CAP website).96

In patients with sporadic medullary

carcinoma, a somatic RET oncogene mutation confers an adverse

prognosis.137

A meta-analysis including 13 studies showed that PD-L1

expression is associated with lower disease-free survival (DFS) (hazard

ratio [HR], 3.37; 95% CI, 2.54–4.48; P .00001) and overall survival (OS)

(HR, 2.52; 95% CI, 1.20–5.32; P = .01) in patients with thyroid cancer.138

Another meta-analysis including 15 studies also showed a significant

association between PD-L1 expression and lower DFS (HR, 1.90; 95% CI,

1.33–2.70; P .001), but OS was not significantly associated with PD-L1

expression.139

Subgroup analyses showed that the association between

PD-L1 expression and DFS was significant for papillary carcinoma (HR,

2.18; 95% CI, 1.08–4.39), but not for poorly differentiated or anaplastic

thyroid carcinoma (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.62–4.32).

Histology

Although survival rates with typical papillary carcinoma are quite good,

cancer-specific mortality rates vary considerably with certain histologic

subsets of tumors.1

A well-defined tumor capsule, which is found in about

10% of PTCs, is a particularly favorable prognostic indicator. A worse

prognosis is associated with anaplastic tumor transformation; tall-cell

papillary variants, which have a 10-year mortality of up to 25%; columnar

variant papillary carcinoma (a rapidly growing tumor with a high mortality

rate); hobnail variant papillary carcinoma, which is associated with

increased rates of local and distant metastasis; and diffuse sclerosing

variants, which infiltrate the entire gland.37,140-142

NIFTP, formerly known as noninvasive encapsulated follicular variant of

papillary thyroid carcinoma (EFVPTC), is characterized by its follicular

growth pattern, encapsulation or clear demarcation of the tumor from

adjacent tissue with no invasion, and nuclear features of papillary

carcinoma.143,144

NIFTP tumors have a low risk for adverse outcomes and,

therefore, require less aggressive treatment.144-148

NIFTP was re-classified

in 2016 to prevent overtreatment of this indolent tumor type as well as the

psychological consequences of a cancer diagnosis on the patient.143,144

A

systematic review including 29 studies showed that the pooled prevalence

rates of NIFTP within EFVPTC and PTC were 43.5% (95% CI, 33.5%–

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-74-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network©

(NCCN©

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma

MS-13

However, some prominent thyroid cancer specialists (including some at

NCCN Member Institutions) oppose this view and advocate unilateral

lobectomy for most patients with papillary and follicular carcinoma based

on 1) the low mortality among most patients (ie, those patients categorized

as low risk by the AMES and other prognostic classification schemes); and

2) the high complication rates reported with more extensive

thyroidectomy.117,191,207

The large thyroid remnant remaining after

unilateral lobectomy, however, may complicate long-term follow-up with

serum Tg determinations and whole body iodine-131 imaging. Panel

members recommend total lobectomy (without RAI ablation) for patients

with papillary carcinoma who have incidental small-volume pathologic N1A

metastases (5 involved nodes with no metastasis 5 mm, in largest

dimension).208

NCCN Panel Members believe that lobectomy alone is adequate

treatment for papillary microcarcinomas provided the patient has not been

exposed to radiation, has no other risk factors, and has a tumor 1 cm or

smaller that is unifocal and confined to the thyroid without vascular

invasion (see Primary Treatment in the NCCN Guidelines for Papillary

[Thyroid] Carcinoma).3,209-212

Total lobectomy alone is also adequate

treatment for NIFTP pathologies (see Tumor Variables Affecting

Prognosis, Histology) and minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinomas

(see Primary Treatment in the NCCN Guidelines for Follicular [Thyroid]

Carcinoma). However, completion thyroidectomy is recommended for any

of the following: tumor larger than 4 cm in diameter, positive resection

margins, gross extrathyroidal extension, macroscopic multifocal disease

(ie, 1 cm), macroscopic nodal metastases, confirmed contralateral

disease, or vascular invasion.3

Note that “gross extrathyroidal extension”

refers to spread of the primary tumor outside of the thyroid capsule with

invasion into the surrounding structures such as strap muscles, trachea,

larynx, vasculature, esophagus, and/or recurrent laryngeal nerve.131,213,214

Completion Thyroidectomy

This procedure is recommended when remnant ablation is anticipated or if

long-term follow-up is planned with serum Tg determinations and with (or

without) whole body iodine-131 imaging. Large thyroid remnants are

difficult to ablate with iodine-131.206

Completion thyroidectomy has a

complication rate similar to that of total thyroidectomy. Some experts

recommend completion thyroidectomy for routine treatment of tumors 1

cm or larger, because approximately 50% of patients with cancers of this

size have additional cancer in the contralateral thyroid lobe.174,215-221

In

patients with local or distant tumor recurrence after lobectomy, cancer is

found in more than 60% of the resected contralateral lobes.218

Miccoli et al studied irradiated children from Chernobyl who developed

thyroid carcinoma and were treated by lobectomy; they found that 61%

had unrecognized lung or lymph node metastases that could only be

identified after completion thyroidectomy.120

In another study, patients who

underwent completion thyroidectomy within 6 months of their primary

operation developed significantly fewer lymph node and hematogenous

recurrences, and they survived significantly longer than did those in whom

the second operation was delayed for more than 6 months.219

Surgical Complications

The most common significant complications of thyroidectomy are

hypoparathyroidism and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, which occur

more frequently after total thyroidectomy.222

Transient clinical

hypoparathyroidism postoperatively is common in adults223

and

children120,224

undergoing total thyroidectomy. The rates of long-term

recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and hypoparathyroidism, respectively,

were 3% and 2.6% after total thyroidectomy and 1.9% and 0.2% after

subtotal thyroidectomy.225

One study reported hypocalcemia in 5.4% of

patients immediately after total thyroidectomy, persisting in only 0.5% of

patients 1 year later.226

Another study reported a 3.4% incidence of

Printed by Cristian Díaz rojas on 12/6/2022 11:33:44 PM. For personal use only. Not approved for distribution. Copyright © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc., All Rights Reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/thyroid-221220101008-dd5cd148/85/thyroid-pdf-79-320.jpg)

![Version 3.2022 © 2022 National Comprehensive Cancer Network©

(NCCN©

), All rights reserved. NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2022

Thyroid Carcinoma

MS-14

long-term recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and a 1.1% incidence of

permanent hypocalcemia.227

When experienced surgeons perform

thyroidectomies, complications occur at a lower rate. A study of 5860

patients found that surgeons who performed more than 100

thyroidectomies a year had the lowest overall complication rate (4.3%),

whereas surgeons who performed fewer than 10 thyroidectomies a year

had four times as many complications.228

Radioactive Iodine—Diagnostics and Treatment

Diagnostic Whole Body Imaging and Thyroid Stunning

When indicated, diagnostic whole body iodine-131 imaging is

recommended after surgery to assess the completeness of thyroidectomy

and to assess whether residual disease is present (see RAI Being

Considered Based on Clinicopathologic Features in the NCCN Guidelines

for Papillary, Follicular, and Hürthle Cell Carcinoma). However, a

phenomenon termed “stunning” may occur when imaging doses of iodine-

131 induce follicular cell damage.229

Stunning decreases uptake in the

thyroid remnant or metastases, thus impairing the therapeutic efficacy of

subsequent iodine-131.230

To avoid or reduce the stunning effect, the

following have been suggested: 1) the use of small doses of iodine-131

(1–2 mCi) or iodine-123 (2–4 mCi); and/or 2) a shortened interval (48–72

hours) between the diagnostic iodine-131 dose and the therapeutic dose.

Iodine-123 is more expensive, and smaller iodine-131 doses have reduced

sensitivity when compared with larger iodine-131 doses.229-231

In addition,

a large thyroid remnant may obscure detection of residual disease with

iodine-131 imaging. Some experts recommend that diagnostic iodine-131

imaging be avoided completely with decisions based on the combination

of tumor stage and serum Tg.229

Other experts advocate that whole body

iodine-131 diagnostic imaging may alter therapy, for example: 1) when

unsuspected metastases are identified; or 2) when an unexpectedly large

remnant is identified that requires additional surgery or a reduction in RAI

dosage to avoid substantial radiation thyroiditis.3,229,232,233

If iodine contrast

agent was used with imaging, then RAI should not begin for at least 2

months after the procedure in order to allow for free iodine levels to

decrease and thus allow for optimal RAI uptake.234,235

Note that diagnostic imaging is used less often for patients at low risk. A

false-negative pretreatment scan is possible and should not prevent use of

RAI if otherwise indicated (see Eligibility for Postoperative Radioactive

Iodine [RAI] in this Discussion, below). For known or suspected distant

metastatic disease, diagnostic whole body iodine-123 or iodine-131

imaging before postoperative RAI may be considered.

Eligibility for Postoperative Radioactive Iodine (RAI)

The NCCN Panel recommends a selective use approach to postoperative

RAI administration. The three general, but overlapping, functions of

postoperative RAI administration include: 1) ablation of the normal thyroid

remnant, which may help in surveillance for recurrent disease (see below);

2) adjuvant therapy to try to eliminate suspected micrometastases; or 3)

RAI therapy to treat known persistent disease. The NCCN Guidelines

have three different pathways for postoperative RAI administration based

on clinicopathologic factors: 1) RAI typically recommended; 2) RAI

selectively recommended; and 3) RAI not typically recommended (see

Clinicopathologic Factors in the NCCN Guidelines for Papillary, Follicular,

and Hürthle Cell Carcinoma).

Postoperative RAI is typically recommended for patients at high risk of

having persistent disease remaining after total thyroidectomy and includes

patients with any of the following factors: 1) gross extrathyroidal extension;

2) a primary tumor greater than 4 cm; 3) postoperative unstimulated Tg

greater than 10 ng/mL; or 4) 6 or more positive lymph nodes or bulky

lymph nodes. In the case of follicular or Hürthle cell carcinoma, extensive

vascular invasion (≥4 foci) is another indication for postoperative RAI.

Postoperative RAI is also frequently recommended for patients with

known/suspected distant metastases at presentation (see