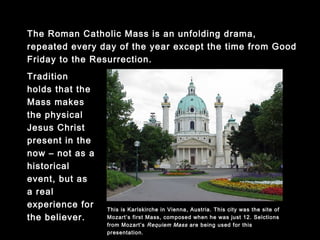

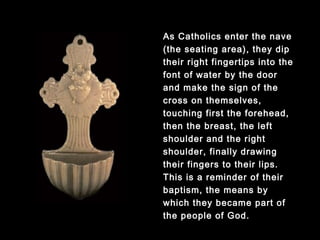

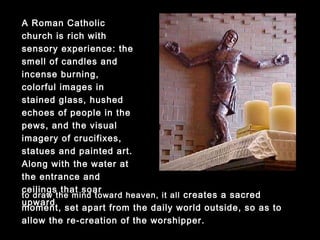

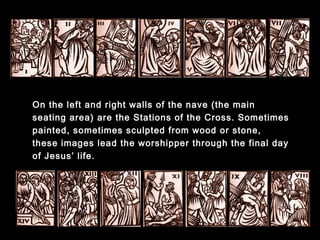

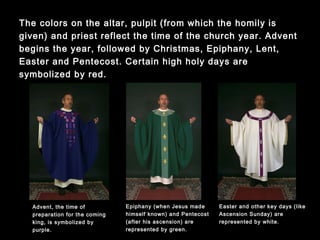

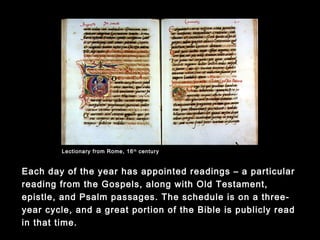

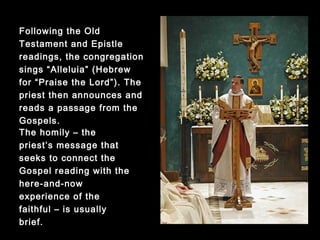

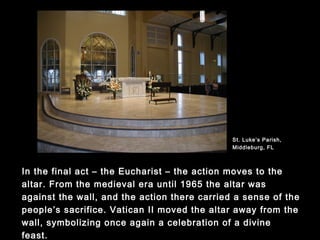

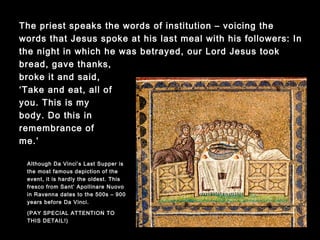

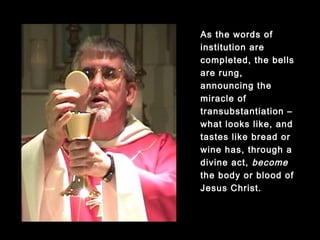

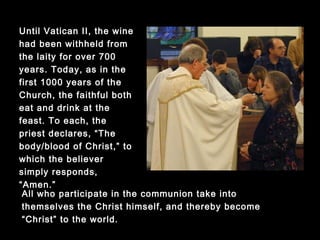

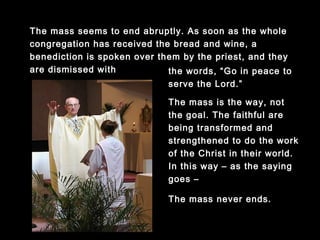

The Roman Catholic Mass follows a dramatic structure with three acts: 1) The entrance rite where worshippers enter and dip their fingers in holy water. 2) The service of the word, where scripture passages are read. 3) The Eucharist, where the bread and wine are consecrated and received as the body and blood of Christ. Throughout the Mass, various rituals and symbols guide worshippers, including stained glass, statues, candles, and changing liturgical colors that mark different seasons. The order of the Mass follows set rubrics but allows for variation based on the occasion being celebrated.