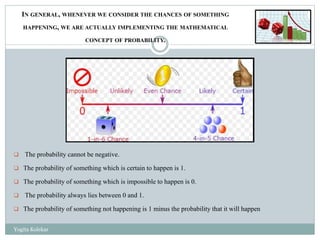

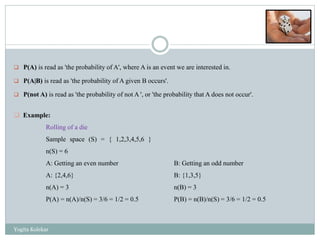

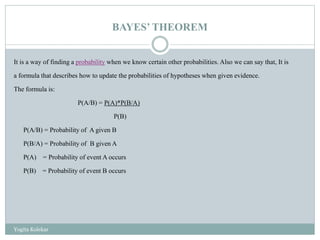

The document outlines fundamental concepts of probability, including definitions, rules, events, conditional probability, and real-life applications. It explains crucial probability rules such as the addition and multiplication rules, along with examples like drawing cards and rolling dice. Additionally, it discusses Bayes' theorem and the significance of probability in various fields like insurance, weather forecasting, and sports strategy.