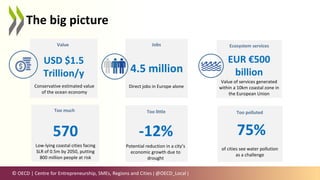

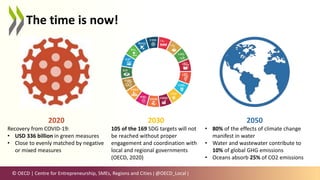

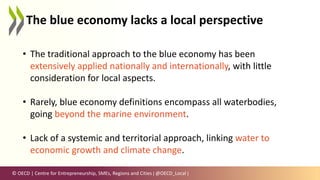

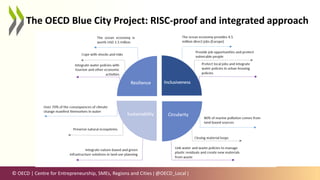

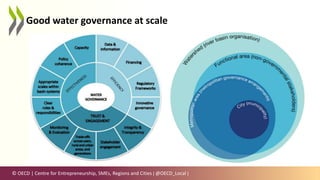

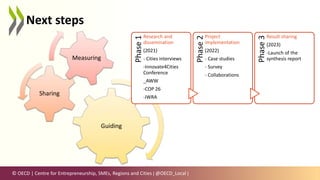

The OECD Blue Cities Project aims to build a sustainable blue economy in cities through an integrated risk-informed and climate-smart (RISC-proof) approach. Coastal cities face risks from sea level rise and water pollution that threaten jobs and economic growth reliant on ocean resources. The traditional approach to the blue economy lacks a local perspective. The project will take a systemic, territorial approach linking water management to local economic development and climate change adaptation through good water governance, sharing knowledge between cities, and measuring project outcomes over multiple phases of research, implementation and result sharing by 2023.