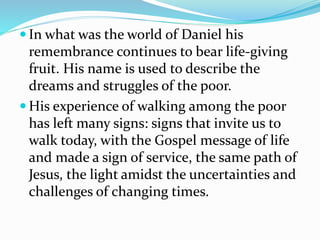

This document provides biographical details about Daniel de la Sierra, a Claretian Missionary priest from Spain who served in Argentina. It describes his upbringing in rural Castile, his religious formation and studies in Rome, and his assignments teaching in Cordoba and pastoral work in the villas miseria (slums) of Buenos Aires. It outlines his commitment to serving the poor through religious, social, and political promotion work. The document also details his transfer in 1981 to neighborhoods in the south of Buenos Aires where he continued pastoral work, relying on his bicycle for transportation.

![ After the novitiate came years of philosophical

studies, undertaken in the so-called College of

Infants in Sigüenza: a place full of memories

since the time of the martyrdom of the young

Fr. José M. Ruiz Cano during the dramatic on

days of 1936. Then, as was the practice then, he

went to do his maestrillo [student teaching] in

some Claretian schools (1957-59): an

experience of missionary life, of practical

transmission of the faith and of teaching to

students. In Segovia on October 24, 1959,

Daniel made his definitive consecration to the

Lord through the profession of perpetual vows.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/themissionbybicycle-170518043713/85/The-mission-by-bicycle-11-320.jpg)